By Mark Wood

During WWI, maritime artist and naval officer Norman Wilkinson proposed that the answer to the growing U-Boat threat, rather than concealment, was for a ship to expose itself to the enemy.

At the commencement of WWI, anti-submarine warfare theory was still in its infancy. There were no instruction manuals on submarine tracking, nor had sub-surface weapons been developed to counter the threat posed by submarines. The initial German U-Boat campaign of 1914 against Britain’s Grand Fleet proved highly successful, resulting in the sinking of nine British warships by the end of the year, including the cruisers Aboukir and Cressy, and the battleship Formidable.

This disastrous beginning to the war forced the Royal Navy to seek safer anchorages off Donegal on Ireland’s North Atlantic coast. The following year, Germany’s campaign of unrestricted submarine warfare saw a dramatic escalation of attacks, and corresponding losses to the Allied merchant fleets. During the first six months of the war only 19 merchant vessels had been lost to U-Boat activity, however in January 1915 alone, the same amount of tonnage was sunk as was destroyed in the previous six months of conflict.

Allied navies resorted to arming trawlers and merchantmen, and some basic tactical instruction was disseminated detailing ideas to counter the U-boat threat, including heading into the line of attack, and attempting to ram hostile submarines.

It was not until 1917 that a Royal Navy officer wrote to the admiralty in London with what he considered might be a possible solution. Norman Wilkinson was a successful painter of maritime seascapes, and an artist for the Illustrated London News, who had set his career aside in 1915 to join the Royal Navy, rising to the rank of Lieutenant Commander in the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve. After submarine service in the Mediterranean, he was transferred to mine-sweeping duties in home waters and it was at this point that his idea for a radical form of effective camouflage began to take shape.

Naval camouflage was not a revolutionary idea. The ancient fleets of the Greeks and Romans had experimented with painting their vessels in shades of blue and green to blend with the surface and horizon, and in the early 20th century, navies of the United States and Europe stipulated shades of grey or off-white in accordance with shipping regulations in an attempt to do the same.

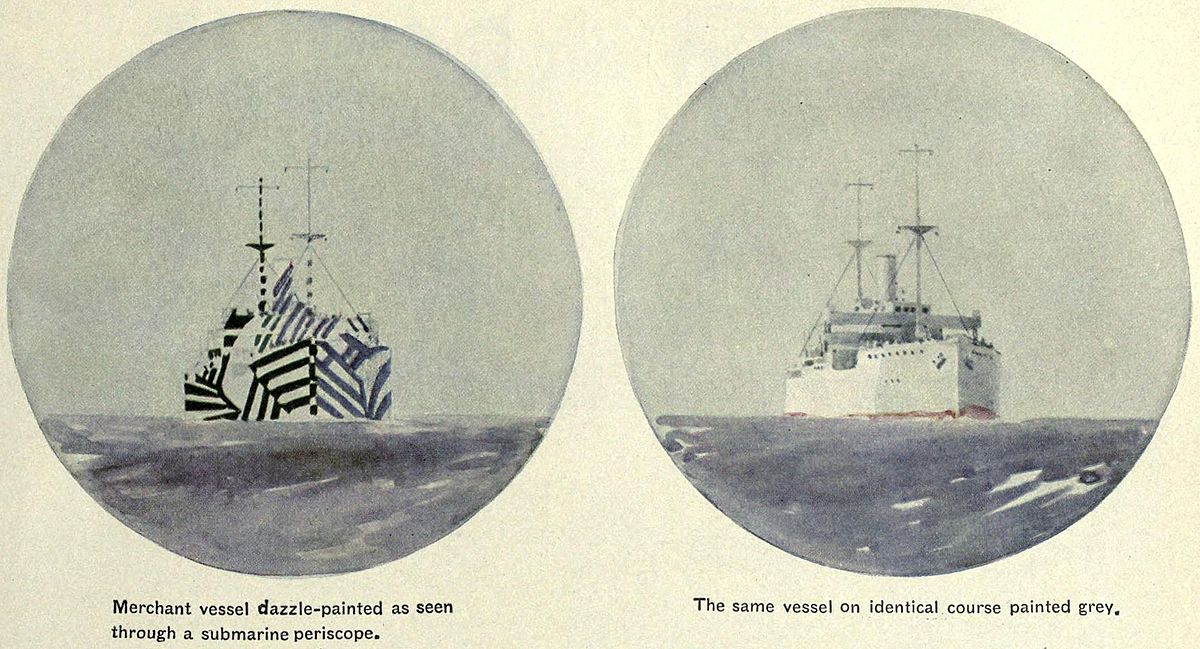

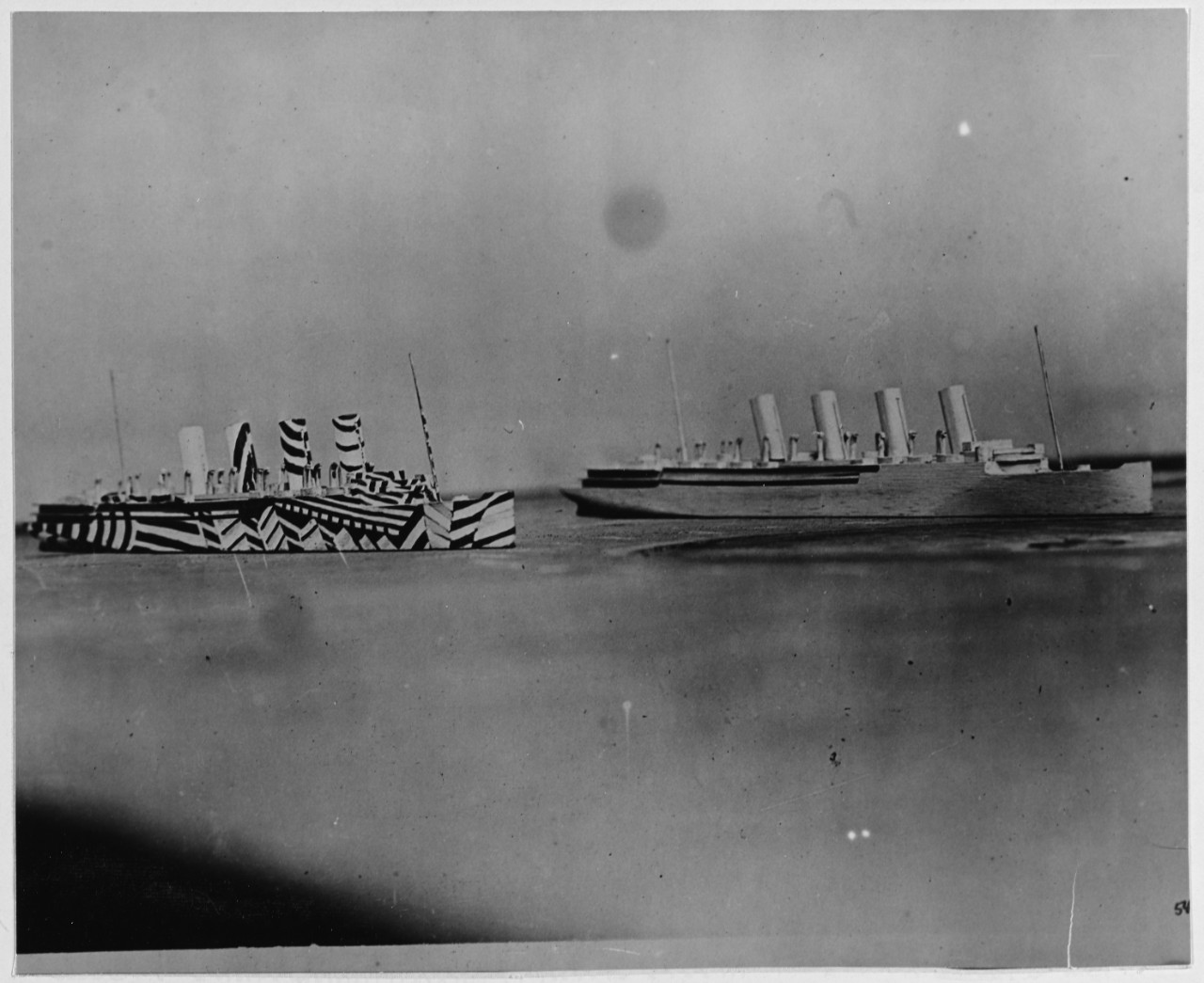

Wilkinson’s idea for dazzle camouflage ran contrary to previous thinking. Instead of attempting to hide vessels from enemy view, he intended that they should be highly visible with the key aim of sowing confusion in the mind of the attacker.

During early submarine operations, the task of computing a fire control solution for a U-Boat commander was a manual process. The target intercept course for a torpedo was calculated using slide rules and based on visual tracking of the current position, course, speed, and range of the vessel to be attacked. This problem was further complicated by the fact that the average speed of a torpedo was between 35 and 45 knots, only moderately faster than most warships of the age, therefore plotting information from a visual fix could be inaccurate at best.

Wilkinson reasoned that geometric dazzle patterns painted on ships would take advantage of the complexity in gauging the optimum firing solution for a torpedo by masking a vessel’s true course and speed, thereby confusing the commanders of German U-Boats and deceiving them into miscalculating the submarine’s fire position.

The bold patterns and extremes of color used in his designs, particularly at the bow and stern would disrupt the visual shape of a vessel, distorting perspective and falsely suggesting that a ship’s smokestacks or superstructure pointed in a different direction than it truly was.

Painted bow curves suggested a bow wave and oblique lines in stripes at the corresponding angles of bow or stern could give the illusion of shortening the vessels length, again confusing the computations of a ship’s attacker. Wilkinson’s ideas borrowed from modernist art concepts of cubism (indeed Picasso, in conversation with the American poet and novelist Gertrude Stein, claimed that the Cubist movement should take credit for its invention), the school of futurism, and its short-lived offshoot, vorticism.

The admiralty initially considered a number of proposals for camouflage schemes, including those from U.S. artist Abbot H. Thayer, whose theories of what he termed “concealing coloration” and “counter shading” were published in 1896 in the Journal of the American Ornithologists Union and are now known as Thayer’s Law. This law was based on the scientist’s many years of observing fauna across the continents of North and South America and concludes that animals are generally dark on top with white under surfaces. Seen from a distance this tends to cancel out the bright sunlight from above and shadow beneath, thereby effectively concealing an animal from potential predators. Thayer demonstrated his ideas to the Department of the U.S. Navy in 1898 during the Spanish-American War, however hostilities came to an end before his proposals could be acted upon.

A Scottish zoologist, John Graham Kerr, developed a keen interest in Thayer’s theories and after meeting in London during the 1890s the two remained lifelong friends, with Thayer forwarding a copy of his book Concealing Coloration in the Animal Kingdom to Kerr in 1914. Kerr’s own approach focused on two main interpretations of his own zoological studies combined with Thayer’s. In compensated shading, a theory he elaborated as “All deep shadows should be picked out in the most brilliant white paint and where there is a gradually deepening shadow, this should be eliminated by gradually shading off the paint from the ordinary grey to pure white.” He suggested a further camouflage scheme he named “parti coloring” which anticipated modern “disruptive pattern” concealment by emphasizing the need to break up the outline of ships by using “strongly contrasting shades.”

While both Thayer and Kerr clearly pioneered the ideas that formed the basis of dazzle camouflage, it was the ideas of Norman Wilkinson that the admiralty board eventually adopted. In recognition of his efforts a post-war award of £2000 was given to him, acknowledging him as the inventor of dazzle camouflage.

The Second World War

Despite the evidence, there was at the time no consensus as to the advantage of using dazzle camouflage, however, Allied naval authorities were sufficiently impressed to continue to employ the idea on both warships and their respective merchant fleets in WWII. The Imperial German Navy had shown little interest in camouflaging their vessels during the Great War and it wasn’t until the Second World War during the invasion of Norway in 1940 that the Germans embraced the possibility of employing the dazzle concept. Photographic evidence of the period shows the hull of the Bismarck painted in a monochrome pattern of dark grey or black and white stripes continuing up onto the superstructure, with the prow and stern area painted black. The intention was to disguise the length of the battleship, creating the impression of a smaller vessel. The heavy cruiser Prinz Eugen was almost identically camouflaged along the waist with extremes of the bow and stern also painted in black, and the battleships Scharnhorst and Admiral Scheer adopted individual dazzle patterns to mask their identities from Allied naval forces. For whatever reason the Kriegsmarine returned to the format of light or dark grey overall for all warships after 1941, whether the senior staff of Oberkommando der Marine were skeptical of the capabilities of geometric camouflage, or whether there were other reasons for the return to pre-war coloring, remains open to debate.

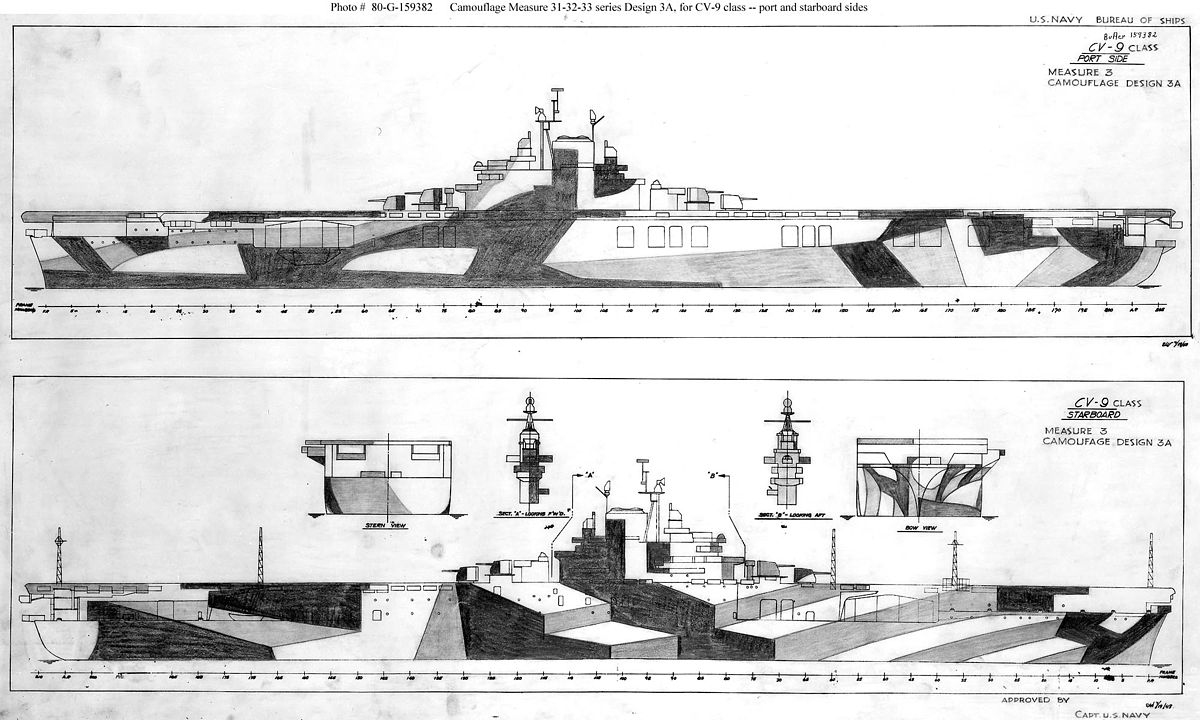

While the German navy discarded dazzle camouflage in the early stages of the war, the Allied navies continued its widespread use throughout hostilities until 1945. After continued analytical and evaluative groundwork at the Naval Research Laboratory in Washington D.C., dazzle camouflage was deemed to be of merit and a phased roll-out was endorsed across respective fleets. In contrast to the Kriegsmarine’s employment of marine camouflage, as an anti-ship/submarine initiative, the U.S. Navy and to a lesser extent the navies of Britain and Canada attempted to use the bold patterns to disrupt attacks by enemy air assets as well as surface ships and submarines. By continuing the geometric shapes across the decks and superstructures of warships. Each ship was painted in its own distinctive camouflage to prevent the enemy from identifying a class of ship, resulting in a diverse array of patterns which made it considerably more difficult to evaluate its effectiveness.

The U.S. Navy implemented the scheme across most classes of vessel from minesweepers and patrol craft to aircraft carriers. Rigorous design, planning and testing was applied to each pattern and a standardized range of colors and shapes were instituted and applied across all theaters including the Pacific, specifically against the Kamikaze threat.

The Royal Navy’s use of dazzle commenced at the beginning of 1940 and was considerably less organised. The admiralty adopted a somewhat laissez-faire attitude to the idea and paint schemes were unofficial and individual to each vessel. It was not until later in the war that the admiralty saw fit to take a more serious view of dazzle camouflage and the navy’s concealment specialists devised geometric patterns which became known as the Western Approaches Schemes, to be employed against the sub-sea threat in the Atlantic. The initiative was developed, and the Admiralty Intermediate Disruptive Pattern was employed in 1942 and was superseded in 1944 by the Admiralty Standard Schemes.

The proliferation of black and white photographic images which have been left to historical posterity, while starkly delineating the vivid lines and curves of dazzle camouflage, are unable to convey the range of color and tone so important to the process of deception. Striking shades of blues, reds, greens and purples contrasted with the light and dark grays which made the experiment so effective.

Eventually post-war technological advances in rangefinding equipment and radar rendered dazzle camouflage largely obsolete, and it fell out of favor in post-war naval thinking.

Was Dazzle Camouflage Effective?

Establishing the effectiveness of Wilkinson’s ideas is almost impossible, not least due to the sheer number of variables to be considered such as color, pattern, and the combination of sizes of ships, vessel speed, and the anti-submarine evasion tactics used. An article in the April 1919 edition of Popular Science considered dazzle camouflage an effective tactic in confusing U-Boat commanders although only at short range and less so than what it termed “low visibility” camouflage.

Arguments continue into the present as to the results of gaudy geometric shapes in protecting ships at sea, but it might certainly be considered the most striking example of art being used to develop a solution in war.

While the United States Navy declared in 1918 that statistical evidence suggested less than one percent of merchant vessels painted in dazzle were sunk, these claims are difficult to substantiate. The testimony of U-Boat commanders who had launched attacks against merchant vessels painted in dazzle camouflage suggests that it was a highly effective countermeasure, even to the point of confusing the issue of the type of ships being attacked and the number of vessels in a convoy. Those convoys that were hit suffered less serious damage than those that were not camouflaged.

While debate over the capabilities of dazzle camouflage continues among naval historians, perhaps the final word should come from the man who officially invented the concept. In an article published in 1920 in the Journal of the Royal Society of the Arts, Norman Wilkinson stated that “The German Admiralty had dazzle painted a liner and had attached her to the submarine training depot at Kiel,” while at the close of hostilities, “a number of the surrendered submarines were painted in precisely the same manner as our merchant vessels.” It is said that imitation is the sincerest form of flattery, and it is this observation by Norman Wilkinson that may answer the question of the worth of dazzle camouflage.

Mark Wood served 15 years in the communications branch of the Royal Navy, with further service in HM Coastguard. After leaving the military he qualified as a history teacher and divides his time between the education sector and working as a freelance writer for military history magazines and websites. Mark is also currently engaged on the Royal Navy First World War Lives at Sea project as a volunteer with the UK’s National Archives.

Featured Image: French cruiser Gloire in dazzle camouflage. (Department of the Navy, Naval Photographic Center)