If you are a current Sailor or member of the Coast Guard, what are some of the biggest impediments to getting your job done? What promised development or technology would most aid you in the accomplishment of your assignment?

This is the third in our series of posts from our Maritime Futures Project. Note: The opinions and views expressed in these posts are those of the authors alone and are presented in their personal capacity. They do not necessarily represent the views of their parent institution U.S. Department of Defense, the U.S. Navy, any other agency, or any other foreign government.

CDR Chuck Hill, USCG (Ret.):

Impediments: The U.S. has the largest Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) in the world. Its area exceeds that of the total land area of the U.S. and most of it is in the Pacific. However, most U.S. Coast Guard assets are in the Eastern U.S. where most of the population (and political clout) resides.

Expedients: Improved Maritime Domain Awareness (MDA) has the potential to assist in search and rescue (SAR), fisheries enforcement, drug interdiction, coast defense, and protections of ports. The Coast Guard cannot afford a comprehensive MDA system solely for its own purposes, but if it can share information with DOD agencies also interested in monitoring the maritime approaches to the U.S., including perhaps cruise missile defense, it could make the employment of assets much more efficient.

LTJG Matt Hipple, USN:

Impediments: The answer is simple. The real impediment is people, time, and flexibility. We have fewer people, which leaves us fewer man-hours and perspectives to get work done. Having fewer people means we have less time… less time for schools, fewer people to run the schools, and less time for training. The training regimen itself has been increased, by more required schools for alcohol awareness, marine species safety, and the like, having little-to-no bearing on the actual work of the sailor. This non-essential training, considered more important and tracked more diligently than regular warfighting training, further drains the pool of man-hours for an already diminished grouping of sailors that, having less time to train or go to school, or spots open in school for them to go, are also less ready than they could be.

Added to that death-spiral between people and time, the Navy is increasingly removing the room for flexibility. While an entire article could be written on the cost-effects of our inflexibility, the fact I can’t, for example, install fire-proof hoses that exceed the necessary requirements without special fleet approval, requiring regular renewing, is itself evidence enough.

LCDR Joe Baggett, USN:

Impediments: Lack of interoperability (Common data networks). Maritime forces are now and will continue to be employed in confidence-building among nations through collective security efforts in a common global system that links threats and mutual interests in an open, multi-polar world. This requires an unprecedented level of integration among our maritime forces, enhanced cooperation with the other instruments of national power, and the capabilities of our international partners. No single nation has the resources required to provide safety and security throughout the entire maritime domain.

LT Drew Hamblen, USN:

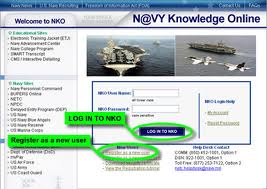

Impediments: The amount of required training extraneous to job proficiency (for example, General Military Training (GMT) requirements on Navy Knowledge Online) is cumbersome and only getting lengthier.

The number of passwords required for our systems is unmanageable and results in personnel writing them down, potentially compromising information assurance, or spending inordinate amounts of time on the phone with NMCI.

NMCI storage (and data storage capacity in general) is severely limited and outages are too frequent.

LT Scott Cheney-Peters, USNR:

Impediments: Others here already address most of what I view as the major impediments to mission accomplishment in the sea services on a day-to-day basis. At a general level these include a dearth of manning (whether afloat, in aviation squadrons, or ashore) and burdensome administrative requirements.

Expedients: Short of increasing manning (not likely), or reducing requirements (possible, and some real efforts have been undertaken, but truly it’s never-ending struggle), there are two areas of focus that could help alleviate the effects. The first is better collaborative tools and sharing of lessons learned. There’s a lot of ‘reinventing the wheel’ that goes on in the fleet, for instance completely different versions of mandatory instructions that only need to be 5% different. This sort of thing can be reduced through better collaborative tools – especially at the squadron or fleet level.

The second is better integration of data streams. Akin to the low levels of communications interoperability, sailors must deal with a multitude of data streams that often require manual integration in the form of data entry. This wastes time and effort. For example, having to manually search online databases for further information about a ship transmitting AIS data to determine its point of origin or destination.

Luckily disaggregated data steams have not escaped notice, especially those from a ship’s organic sensors, resulting in general trends to develop all-encompassing combat system suites rather than stand-

alone weapon and sensor systems. AIS, for example, is today better integrated into navigation displays, and it seems logical it will be integrated into future combat systems suite upgrades. The trend for aggregated data is also progressing in remote-site monitoring, enabled by better sensors throughout things such as a ship’s engineering plant, helping displace some manually integrated data streams generated by the old Mark I Eyeball. But data streams for administrative tasks – true data entry between different IT and web-based programs, or just plain old excel spreadsheets – still have a long way to go. IT certificates and tokens can reduce some of the most redundant data-entry requirements (e.g. “type in your name, rank, and date of birth”), but there’s still a long way to go. And, with increasing reliance on inter-accessible and integrated data comes the need for better cyber defenses, whether ashore or afloat.

Rex Buddenberg, U.S. Naval Postgraduate School:

Impediments: From a programmatic point of view we keep fixating on platforms (i.e. new

cutters, Deepwater, Navy FYDP shipbuilding, and LCS) rather than making

the platforms work together. We need to focus on integration.

YN2(SW) Michael George, USN:

Impediments: As a Yeoman dealing with primarily administrative functions, I am usually able to perform my job duties and responsibilities with simply a computer, printer, and some pens, so there’s not much need for improvement on the hardware side. However, the current setup of processing personnel administrative information uses collateral-duty Command Pass Coordinators (CPCs) and an online system (TOPS) that correspond with ashore Personnel Support Detachments (PSDs) for all matters of pay and personnel support. This is a good idea in theory to help reduce shipboard manning, but it’s handled poorly, as it grants junior Sailors at PSDs across the fleet the power to supersede orders simply because the person giving the order is not a CPC. It also causes people like myself in the Yeoman rate (and worse, many ENs, LSs, CMs, and more) to spend an inordinate amount of time on collateral duties, handling personnel paperwork that members used to be able to go directly to their PSD or a true shipboard expert to handle.

LT Jake Bebber, USN:

Impediments: The biggest impediment to maritime cryptology is not a piece of equipment … it is the lack of leadership in the cryptologic spaces. We need to refocus our cryptologic space-leaders – the LPOs, the Division Chiefs, and the JOs – and reorient them to emphasize the quality and quantity of cryptologic reporting. This can be done by simply “getting back to the basics” of maritime cryptology and practicing sound fundamentals. Too often, we are complacent because the advanced equipment we use can appear to do the work for us. But the most important piece of equipment in a cryptologic space is what’s between the ears, not the new computers or gear. Our cryptologic leaders – especially Chiefs – need to be present in the spaces, ensuring quality and teaching fundamentals. The JOs need to be there as well, learning from their Chiefs, LPOs and subject matter experts instead of standing watches on the bridge or combat. Too much time is being spent by JOs and Chiefs doing things not related to the cryptologic mission, outside the cryptologic space.