By Jonathan Panter

On March 18, 2021, former Congresswoman Elaine Luria of Virginia criticized the Navy’s then-recently-released Unmanned Campaign Framework as “full of buzzwords and platitude but really short on details.” When promised a classified concept of operations, she added, “I think the biggest question I have [is]… it is a fleet to do what?”

Two and a half years later, the American public – soon to spend half a billion dollars on unmanned vessels – could ask the same thing. What strategic ends are unmanned vessels intended to serve? The Navy has yet to update the Unmanned Campaign Framework. The document promises all the right things (“faster, scalable, and distributed decision-making”; “resilience, connectivity, and real time awareness”) but provides little granular detail about the differential utility of unmanned systems across mission and warfare areas.

Nevertheless, unmanned vessels are receiving more attention than ever. The media frenzy surrounding Ukraine’s “drone boats” continues; the Navy’s Task Force 59 (responsible for testing small unmanned surface vessels in the Persian Gulf) gets the feature-length treatment in Wired; and a front-page article in the New York Times all but lobbies for more unmanned ships.

Perhaps a concept of operations for unmanned surface vessels is floating around in the classified world. But elsewhere, buzzwords still rule the day. Just weeks ago the Department of Defense announced its new “Replicator” initiative to deploy thousands of drones within two years: it will be “iterative,” “data-driven,” “game-changing,” and of course, “innovative” (variations of the latter appear 22 times in the announcement). Never mind that, in warfare, “innovative” is not always synonymous with “useful.”

Part of the problem is conceptual. The term “unmanned system” includes everything from a civilian hobbyist quadcopter used for spotting artillery in Ukraine, to the Navy’s as-yet-unbuilt “large unmanned surface vessel,” a tugboat-sized ship that is supposed to launch cruise missiles. This expansive terminology can confuse lay observers or new students of the subject. Unmanned systems have matured at different rates. Some have been thoroughly tested and proven their mettle in real-world operations; others are, at present, theoretical or even daydreams. The U.S. military has decades of experience operating unmanned aerial systems (or “aerial drones”), for instance. But the record of unmanned surface vessels – the focus of this article – is limited. Only two types of unmanned surface vessels have seen operational duty in the current era: Ukraine’s (decidedly non-autonomous) explosive-laden drones, and the U.S. Navy’s tiny “Saildrone,” a vessel with little current purpose besides visually-identifying other ships in a permissive environment. Despite these narrow use cases, the two examples are almost-unfailingly invoked in claims that a naval revolution is underway.

When the same few words, and the same few examples, so frequently justify a wholesale strategic pivot, policymakers and strategists should take pause. If the Navy intends to reorient its ways and means of warfare – and if the taxpayer is expected to pay for it – then Congress and the American people deserve a formal, public strategy document on the general purposes and risks of unmanned surface vessels.

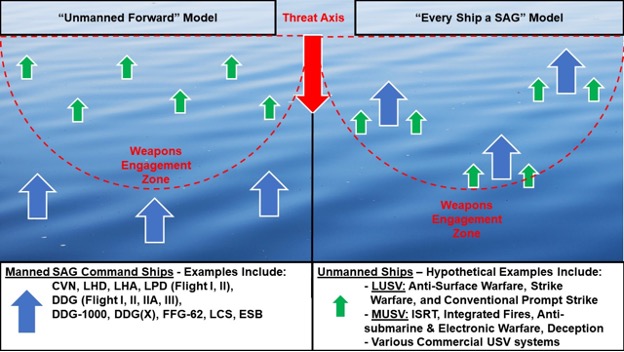

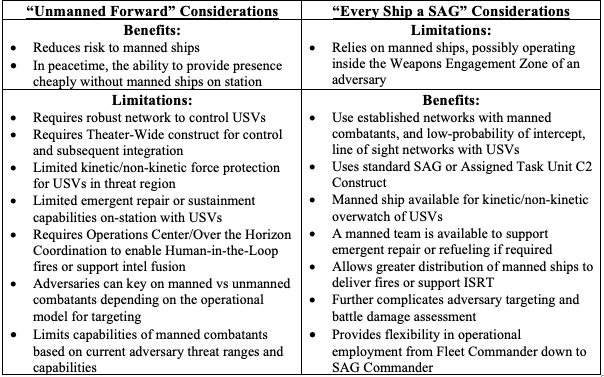

The Missions of the Navy

The 2021 Unmanned Campaign Framework is less a plan than a promotional pamphlet. The Framework dedicates one page each to the Department of Defense’s four unmanned systems “portfolios” – air, surface, subsurface, and ground – an understandably brief introduction given the infancy of the technology and classification concerns. Because specific programs are prone to change, it is more informative to examine the promise of unmanned systems from the perspective of the underlying strategic motivation for their development. That context is a shift to what the Navy calls “distributed maritime operations”: a plan to field more platforms, in a more dispersed fashion, networked together to share information and concentrate fires, while keeping people outside the enemy’s weapons envelope, and sending more expendable assets inside of it. Unmanned ships, the Framework contends, free up humans for other tasks, reduce the risk to human life, increase the fleet’s persistence, and make it more resilient by providing more “nodes” in the network. They are also – the Navy frequently claims – cheap. The Chief of Naval Operations’ Navigation Plan 2022 also promises that unmanned systems will deliver particular means of warfare (e.g., increased distribution of forces) but again, without specifying the differential application of such means across mission and warfare areas.

The first step in determining the likely future distribution of unmanned surface vessel risk is projecting where those vessels are most likely to be used. Setting aside strategic deterrence, which remains the realm of ballistic missile submarines, the Navy’s core four missions are sea control, presence, power projection, and maritime security.

Forward Presence is the practice of keeping ships persistently deployed overseas, demonstrating U.S. capabilities and resolve, in order to deter adversaries and reassure allies. Unmanned ships’ putative “advantages” – that they are cheap, small, expendable, and don’t risk personnel – are decidedly counterproductive for this purpose. Deterrence and reassurance require convincing adversaries and allies that one has skin in the game, and risking an unmanned asset hardly compares to risking a destroyer and her crew. On the other hand, the Navy’s large and medium unmanned surface vessels, if ever successfully fielded (and there are ample reasons to suggest that severe challenges remain) might contribute to the credible combat power that deterrence requires.

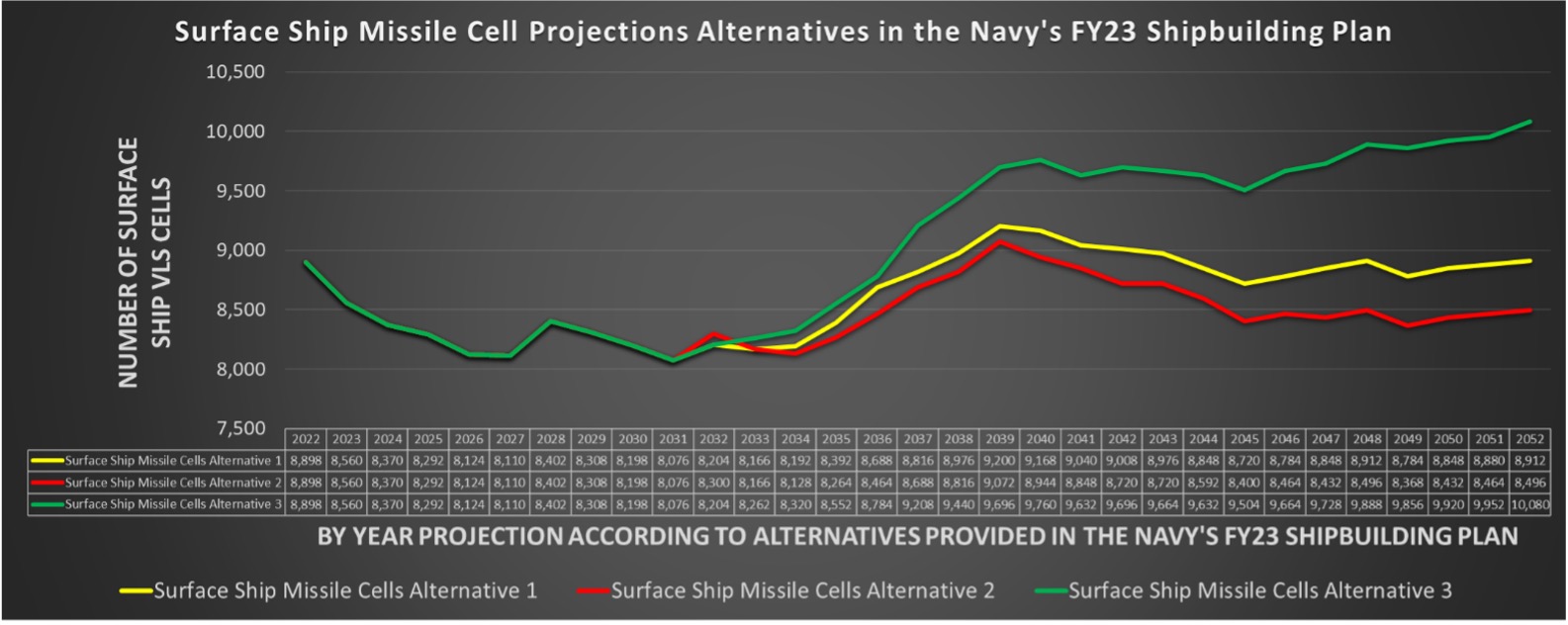

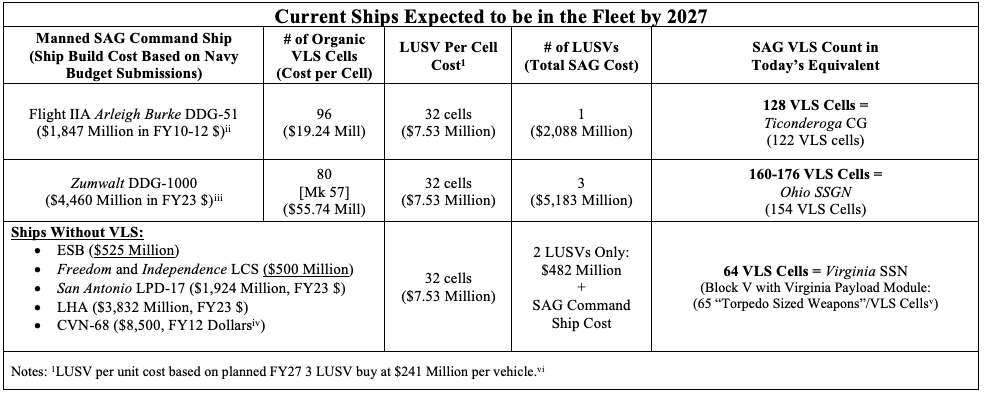

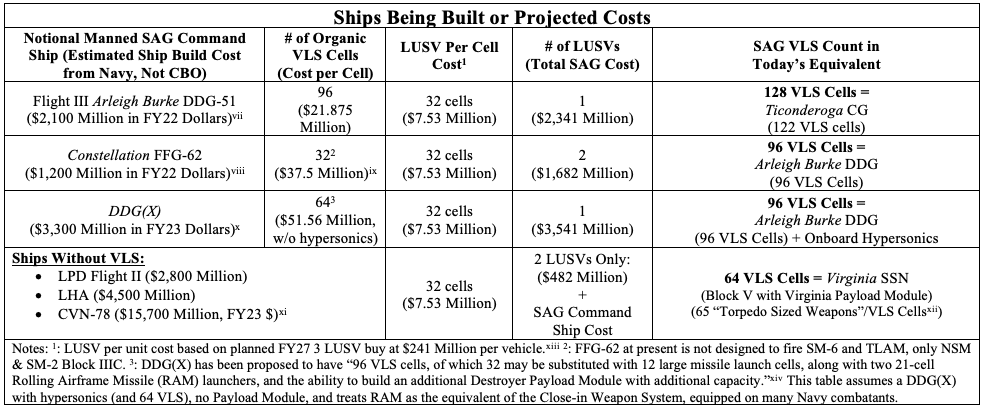

Another possible argument is that unmanned vessels will free up manned ships for those specific presence operations where a human touch is invaluable (such as port visits), reducing strain on the fleet. But that raises a conundrum. For a ship to demonstrate credible combat power, it must be able to shoot. And the Navy has made clear that any unmanned ship with missiles and guns will be under human control. Particularly in the next few decades, when unmanned vessels’ maintenance and support requirements will be high, nearby manned ships will probably provide that control. Hence, while unmanned vessels could increase the fleet’s vertical-launch capacity – and therefore its combat credibility – they may also worsen operational tempo or contribute to higher overall costs.

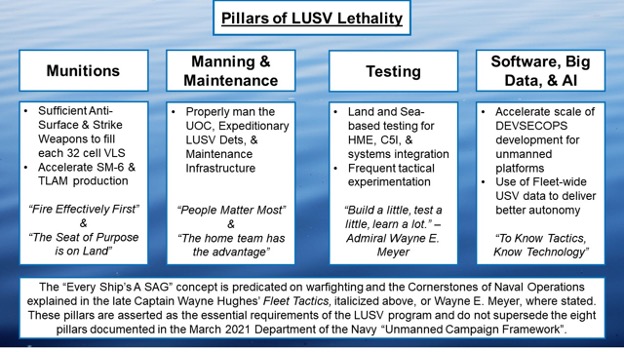

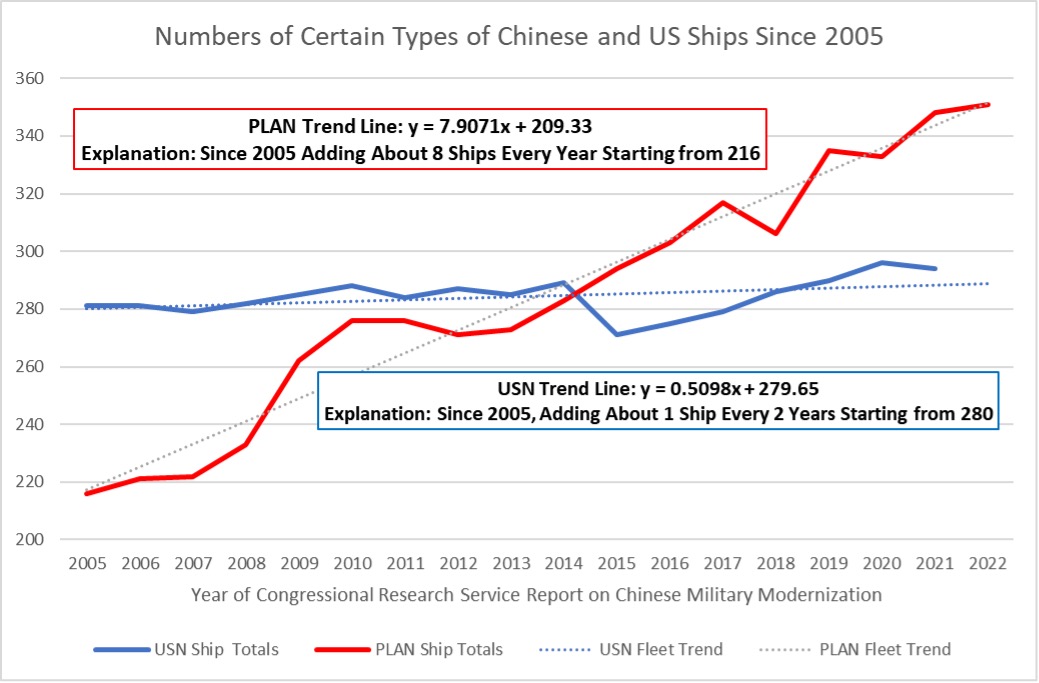

Power Projection is the use of ships to fire missiles, launch aircraft, land troops, or provide logistical resupply in support of combat operations on land. The Navy’s large unmanned surface vessel is expected to serve this mission by swelling the Navy’s capacity to launch land-attack missiles. Destroyers and guided missile submarines already serve this function, but unmanned vessels will, according to their advocates, do so more cheaply and with less human risk. But since manned assets’ capabilities in this area are proven, and unmanned assets’ capabilities are not, the Navy must explain what happens if the new technologies fail, and the traditional fleet – perhaps prematurely shrunken or reordered to accommodate the unmanned systems – has to step in to pick up the slack. Unmanned vessels are not officially intended to “replace” manned warships, but a significant strategic imperative for their development is the Navy’s tacit acknowledgment that, given constrained budgets, it cannot achieve its desired fleet expansion with manned ships alone.

Sea Control is attacking enemy ships, aircraft, and submarines, so that the U.S. and its allies can use the sea for power projection or make it passable for wartime commerce. Its corollary is sea denial: preventing an enemy from using of the sea for his purposes. This is where unmanned surface vessels are really supposed to shine. The two biggest arguments for their value-add in sea control are intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance (ISR), and increased anti-ship missile capacity. There are also interesting emerging use cases, such as swarming electromagnetic warfare.

Small unmanned surface vessels, like the Saildrone – the argument goes – can loiter in large numbers, for weeks at a time (using solar power), all over a battlespace, looking and listening for enemies. While such a niche case for surveillance can be useful, the problem is that maritime surface ISR can struggle to match the global access and persistence of space-based and airborne ISR. Even in relatively constrained areas like the East and South China Seas, the search areas are vast. Unmanned surface vessels cannot match the revisit rates of low earth orbit satellites when combing large swaths of the ocean’s surface. In the last few years, the vast growth in low-earth orbit satellite constellations (both commercial and government-owned) has further diminished the urgency and budget efficiency of meeting ISR needs with surface ships. Ironically, the Saildrone and similar craft may end up being more dependent on space, because unmanned surface ISR assets operating over the horizon will rely on satellite communications to send mission data back. As for airborne ISR (that conducted by manned or unmanned aircraft), small unmanned surface vessels deployed en masse can exceed the persistence of aircraft, but at the cost of sensor reach: these vessels’ low “height of eye” inherently limits the range of their electro-optical sensors.

That relates to the second role unmanned ships are expected to serve in the sea control mission: offensive surface warfare. As noted, the Navy has been explicit that any unmanned ship with kinetic capabilities will be controlled by humans. As such, these vessels cannot be compared to, say, a command-guided missile that switches to radar in the terminal phase. Any kinetic-equipped unmanned vessel will rely on over-the-horizon communications relay provided by satellites, manned and unmanned surface vessels, or airborne assets. But if the Navy expects a satellite-degraded environment, as is possible in a conflict with a peer competitor, then surface and airborne assets will substantially assume the relay burden (requiring far greater numbers of them). Considering the Navy’s stated intent that most unmanned assets be “attritable,” however, it remains to be seen how long such a distributed network would last before manned vessels must themselves assume the relay function, bringing them closer to the enemy’s weapons engagement zone.

Maritime Security refers to constabulary functions such as protecting commerce from terrorists and pirates and preventing illegal behavior such as arms smuggling and drug running. In such operations, small and medium unmanned surface vessels could technically conduct surveillance, issue warnings, or engage threats with small-caliber weapons while under remote human control. The latter, however, seems especially unlikely in practice. Maritime security is a peacetime endeavor, conducted in congested sea space among civilians. Accordingly, there is a high premium on positive identification of bad actors, and generally the goal is not to kill anyone. A human touch will be required – not just “in the loop,” but probably on-scene.

Another problem is that, if unmanned vessels are small and cheap – two of their most celebrated characteristics – terrorists and drug runners may be able to disable them quite easily. Saildrone, therefore, adds most value for maritime security ISR under the following narrow set of conditions: when no aviation assets, satellite coverage, or allied coast guards are available; manned ships or shore facilities are within communications range; it is sunny, or enough sunny days have recently passed to keep batteries charged; and the targets of surveillance are incapable of shooting at, or (as with Iran in 2022), attempting to capture the drone monitoring them from within visual range.

The Risks of Concentration

Most contemporary Navy ships can be used for a variety of the missions delineated above. Destroyers can be used for power projection, sea control, presence, and maritime security; aircraft carriers can be used for all of those; amphibious assault ships are best for power projection and presence but can readily support maritime security. None of this is true for any unmanned vessel – not any in production, and none even in the design phase. A large unmanned surface vessel will have one purpose: to support power projection. Medium unmanned surface vessels will have two purposes: to contribute to sea control and maritime security.

Multi-mission capability, however, is not necessarily the goal. Unmanned assets, proponents argue, will not replace manned ships, but rather augment them as part of a “hybrid fleet.” The Navy expects a force structure that is 40 percent unmanned by 2050, although that does not mean that each naval mission area will be 40 percent unmanned. Some missions will rely more heavily on unmanned platforms than others will. This means the risks of unmanned vessels will not be evenly distributed across the Navy’s missions.

In general, we can forecast that unmanned vessels will fall out of operation (in peacetime) or attrite more quickly (in wartime) than manned ships for two reasons. First, the technology is immature and likely to remain so for a long time; currently, unmanned vessels are prone to inherent hull, mechanical, and electrical casualties, and cyber vulnerabilities. In brief, persistence is these vessels’ greatest challenge (and one the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency is attempting to solve). Unmanned vessels may be required to keep station for weeks or months, in contrast to aerial drones’ persistence times, which are measured in hours. The longer unmanned surface vessels are at sea without maintenance, the greater their chance of routine equipment failure that either requires remote troubleshooting or on-scene repair. The former incurs both electromagnetic targeting and cyber risk. Second, unmanned vessels are explicitly designed to be less survivable, or “expendable” in the words of proponents.

The New York Times feature article mentioned previously illustrates the problem. It observes that the Navy has not scaled the success of Saildrone by integrating larger unmanned surface vessels into the fleet. This failure is attributable, the article argues, to bureaucratic inertia and industry capture. Missing from the discussion is the fact that the hull, mechanical, and electrical solutions required to field a 2000-ton medium unmanned surface vessel (especially one capable of persistent operations) are an order of magnitude more complex than those required for the 14-ton Saildrone. The propulsion requirements alone, let alone combat systems, place the former decades behind the latter in technological maturity. It is therefore nearly guaranteed that by 2030, for instance – even if the Navy has increased the overall percentage of unmanned vessels in its force structure – the Navy will not be able to have significant numbers of unmanned vessels in key mission areas.

Accordingly, the Navy must assess concentration risk: what happens when certain missions, but also warfare areas within those mission areas, degrade at different rates due to the differential survivability of manned versus unmanned assets. As a thought experiment, let us assume the Navy hits its 40 percent unmanned target. However, because Saildrones are far less technically complex, and far cheaper, than large unmanned surface vessels, the future fleet has more of the former than the latter. That future fleet would therefore be more reliant on unmanned assets for maritime security than for presence. Suppose, then, that China executes a successful cyber attack against a network of Saildrones; suddenly the maritime security mission is compromised, and the Navy must draw on its manned assets to support it – at the expense of the presence mission.

Sound unrealistic? Ukraine recently hacked Iranian-made drones used by Russia; during the Solar Winds hack, malicious code was delivered via legitimate code process; and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s satellite network was hacked on at least one known occasion. And these are only some of the reasons why any unmanned asset with external communications capability must be assumed as cyber-vulnerable by default.

Beware Innovation for Innovation’s Sake

It should make the hairs stand up on the back of one’s neck when a new capability is described as simultaneously cheaper and more effective; when dozens of articles use the same buzzwords; when strategy documents are heavy on sweeping generalizations and light on detail; when the claim that technology will “mature” is delivered as a certainty; when “innovative” is treated as synonymous with “useful;” or when the same few empirical examples appear in every article on a subject. All of these are present in spades in media coverage of unmanned vessels.

If the U.S. Navy is to embark on a costly project with uncertain chances of success, it owes Congress and the American people a better Unmanned Campaign Framework, or an unclassified concept of operations that disaggregates the role of unmanned ships across the Navy’s various missions, and the warfare areas that comprise them. Such a concept must be honest about concentration risk and suggest ways to mitigate it. And Congress, which has already begun to take a deeper interest in unmanned platforms, should hold the Navy to account.

Jonathan Panter is a Ph.D. Candidate in Political Science at Columbia University. His dissertation examines the strategic logic of U.S. Navy forward presence. Prior to attending Columbia, he served as a Surface Warfare Officer in the U.S. Navy.

The author thanks Anand Jantzen and Ian Sundstrom for comments on an earlier draft of this article.

Featured Image: NAVAL STATION KEY WEST, Fl. – (Sept. 13, 2023) Commercial operators deploy Saildrone Voyager Unmanned Surface Vessels (USVs) out to sea in the initial steps of U.S. 4th Fleet’s Operation Windward Stack during a launch from Naval Air Station Key West’s Mole Pier and Truman Harbor(U.S. Navy photo by Danette Baso Silvers/Released)

e discuss the Office of Naval Research (ONR’s)

e discuss the Office of Naval Research (ONR’s)