By Alex Calvo

Introduction

Despite repeatedly stating that it will not take sides in territorial disputes in East Asia, Washington remains keenly interested in the ultimate fate of the South China Sea. In addition to perennial calls to settle disputes peacefully, regular reminders of the importance of freedom of navigation, military aid to regional actors like the Philippines, and support for a more active policy by non-littoral maritime democracies like India and Japan, the US Department of State (DOS) took a further step late last year by issuing a document, part of its “Limits in the Seas” series. The text seeks to explain the different ways in which one may interpret Chinese maritime claims in the South China Sea (“that the dashes are (1) lines within which China claims sovereignty over the islands, along with the maritime zones those islands would generate under the LOS Convention; (2) national boundary lines; or (3) the limits of so-called historic maritime claims of varying types”). It concludes that the “dashed-line claim does not accord with the international law of the sea” unless “China clarifies that” it “reflects only a claim to islands within that line and any maritime zones.” The text includes supporting Chinese official views, without attributing “to China the views of analysis of non-government sources, such as legal or other Chinese academics.” Concerning this latter restriction, although it is of course official sources which may be considered to be most authoritative when it comes to interpreting a government’s position, we should not forget that administrations in different countries will often resort to “two-track diplomacy” or employ semi or non-official back channels to test the waters and lay the groundwork for future formal negotiations.

[otw_shortcode_button href=”https://cimsec.org/buying-cimsec-war-bonds/18115″ size=”medium” icon_position=”right” shape=”round” color_class=”otw-blue”]Donate to CIMSEC![/otw_shortcode_button]

The object of this five-part series is to summarize the DOS document, while commenting on some of its most relevant features, and where appropriate going beyond the text and examining related aspects of the South China Sea conflict.

Tyranny of History: Can Washington claim not to take sides on Filipino territorial claims?

Before summarizing the “Limits in the Seas” document, we should note that the American policy of not taking sides concerning the ultimate issue of sovereignty could be challenged given Washington’s past sovereignty over the Philippine Archipelago. While this has not been publicly stressed by Manila to date, it could enter the debate as a means of putting more pressure on Washington to adopt a more robust posture.

Chinese Claims and Possible Interpretations According to International Law

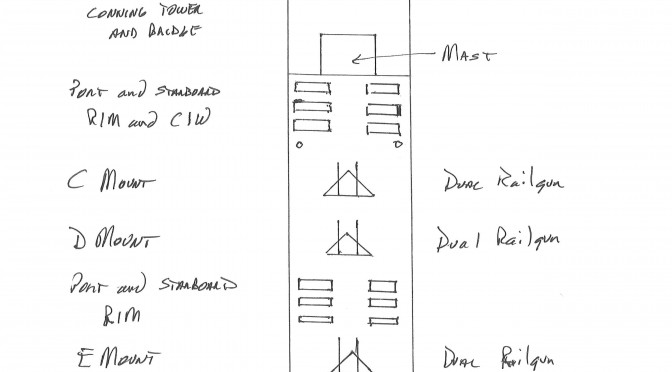

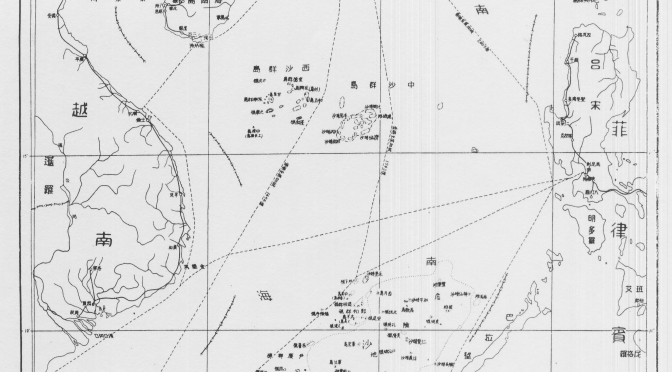

In line with long-standing US demands that Beijing clarify the ultimate nature of her South China Sea claims, the DOS document analyzes those figures within UNCLOS and customary international law which may provide cover to Beijing’s claims. Issued on 5 December 2014, the Department of State paper begins by stressing that “China has not clarified through legislation, proclamation, or other official statements the legal basis or nature of its claim associated with the dashed-line map”, explains the “origins and evolution” of the dashed-line maps, provides a summary of the different maritime zones recognized and regulated by UNCLOS, and then proceeds to explain and discuss three possible interpretations of that claim “and the extent to which those interpretations are consistent with the international law of the sea.” The document contains a number of maps, including (Map 1) that referred to in China’s two May 2009 notes verbales to the UN Secretary General, which stated that “China has indisputable sovereignty over the islands in the South China Sea and the adjacent waters, and enjoys sovereign rights and jurisdiction over the relevant waters as well as the seabed and subsoil thereof. The above position is consistently held by the Chinese government, and is widely known by the international community.”

A Look at Chinese Map Quality and Accuracy

The text first outlines the history of China’s maps of the South China Sea containing dashed lines, starting with a 1947 map published by the Nationalist government, noting that later PRC maps “appear to follow the old maps” (see L. Jinming and L. Dexia, “The Dotted Line on the Chinese Map of the South China Sea: A Note”, Ocean Dev’t & Int’l L., Volume 34, 2003, pp. 287-95, p. 289-290) with two significant changes: the removal of two dashes inside the Gulf of Tonkin (in an area partly delimited by Vietnam and the PRC in 2000) and the addition of a tenth dash to the East of Taiwan. These two changes can be interpreted in different ways, to some degree contradictory. On the one hand, the partial delimitation agreement with Vietnam could be seen as evidence of Chinese pragmatism and flexibility, and proof that it is possible for countries in the region to at least partly settle their disputes by diplomacy. On the other, explicitly encompassing Taiwan with an extra dash may be seen as a reinforcement of Chinese claims on the island not necessarily based on the will of her population. Alternatively, it could simply be a way to more comprehensively encompass the waters and features that Beijing (either directly or via Taipei) wishes to master.

The paper then examines successive Chinese maps from a cartographic perspective, stressing that “China has not published geographic coordinates specifying the location of the dashes. Therefore, all calculations in this study relating to the dashed line are approximate.” A similar criticism has sometimes been made of the San Francisco Treaty. The text also notes that “China does not assign numbers to the dashes,” and therefore those in the study are for “descriptive purposes only.” They “are not uniformly distributed,” being “separated from one another by between 106 (dashes 7 and 8) and 274 (dashes 3 and 4) nautical miles (nm).” This section of the paper stresses that “Nothing in this study is intended to take a definitive position regarding which features in the South China Sea are ‘islands’ under Article 121 of the LOS Convention or whether any such islands are ‘rocks’ under Article 121(3).” This is in line with Washington’s refusal to take sides concerning the ultimate sovereignty disputes in the region. The text notes that the “dashes are located in relatively close proximity to the mainland coasts and coastal islands of the littoral States surrounding the South China Sea,” and explains that, for example, Dash 4 is 24 nm from Borneo’s coast, part of Malaysia. Generally speaking, “the dashes are generally closer to the surrounding coasts of neighboring States than they are to the closest islands within the South China Sea,” and as explained later this is significant when it comes to interpreting the possible meaning of China’s dashed line, since one of the principles of the Law of the Sea is that land dominates the sea, and thus maritime boundaries tend as a general rule to be equidistant. That is, maritime boundaries tend to be roughly half way between two shores belonging to different states.

To hammer home this point, the study includes a set of six maps illustrating this. The report criticizes the technical quality of the PRC maps, saying that they are inconsistent, thus making it “complicated” to describe the dashed line, whose dashes are depicted in different maps “in varying sizes and locations.” Again, this is important in light of possible interpretations of Chinese claims, since this lack of consistency and quality not only obfuscates Chinese claims, introducing an additional measure of ambiguity, but also makes it more difficult to ascertain whether historical claims are being made and whether they are acceptable in light of international law.

The dashes change from map to map, with those “from the 2009 map” being “generally shorter and closer to the coasts of neighboring States” than those in the 1947 map. The dashed lines in these two maps are illustrated and compared in Map 5 of the document. The section concludes noting that the 2009 map, which Beijing distributed to the international community “is also cartographically inconsistent with other published Chinese maps.”

Read the next installment here.

Alex Calvo is a guest professor at Nagoya University (Japan) focusing on security and defence policy, international law, and military history in the Indian-Pacific Ocean. Region. A member of the Center for International Maritime Security (CIMSEC) and Taiwan’s South China Sea Think-Tank, he is currently writing a book about Asia’s role and contribution to the Allied victory in the Great War. He tweets @Alex__Calvo and his work can be found here.

[otw_shortcode_button href=”https://cimsec.org/buying-cimsec-war-bonds/18115″ size=”medium” icon_position=”right” shape=”round” color_class=”otw-blue”]Donate to CIMSEC![/otw_shortcode_button]

This was a necessary move to both reassure America’s allies and partners in the region of America’s commitment and to uphold common sense interpretations of the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). What many pieces of analysis gloss over is that even though UNCLOS is pretty clear that the reclamation doesn’t turn reefs into islands or give them the rights of islands, interpretations of international law – if contested – must be backed up by words and actions. Otherwise the counter-vailing view gains acceptance as customary international law.

This was a necessary move to both reassure America’s allies and partners in the region of America’s commitment and to uphold common sense interpretations of the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). What many pieces of analysis gloss over is that even though UNCLOS is pretty clear that the reclamation doesn’t turn reefs into islands or give them the rights of islands, interpretations of international law – if contested – must be backed up by words and actions. Otherwise the counter-vailing view gains acceptance as customary international law.