The following essay is adapted from a report published by George Mason University’s Center for Security Policy Studies: A Question of Time: Enhancing Taiwan’s Conventional Deterrence Posture

By Joe Petrucelli

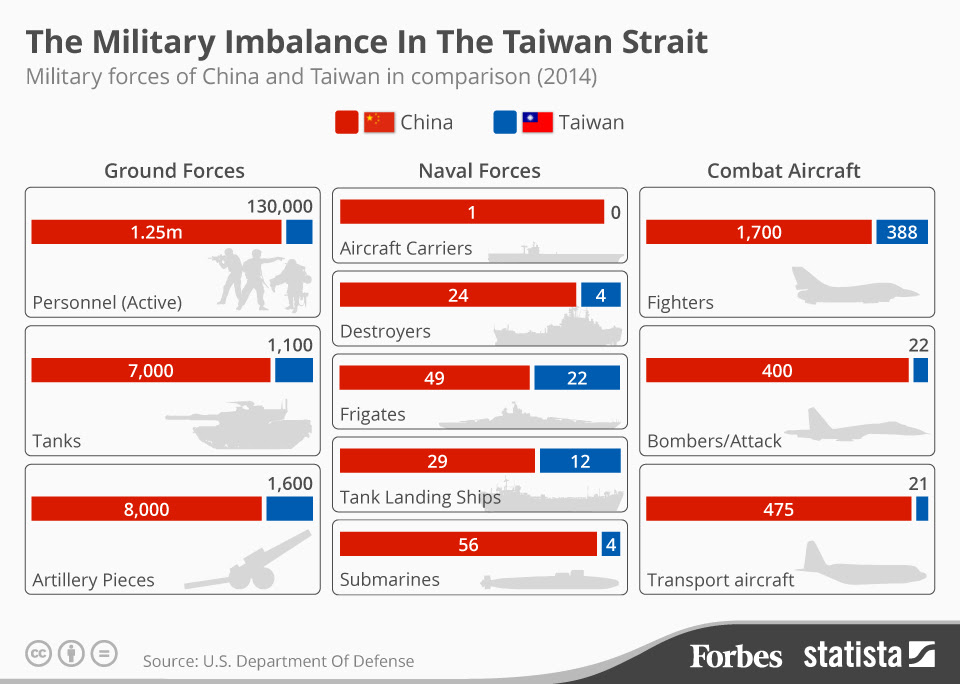

Just last month two U.S. Navy warships conducted a transit of the Taiwan Strait, reminding the world that the status of Taiwan remains contested and unresolved. Although China prefers to use peaceful means to achieve unification, it has not taken the possibility of force off the table. Accordingly, Taiwan remains one of the few states to endure the plausible risk of military invasion.

After visiting Taiwan to study this problem, a team of researchers, including the author, recently released a report advocating for a dramatic shift in Taiwan’s conventional deterrence posture. Among our recommendations, we call for Taiwan’s navy to change its current acquisition priorities and embrace an unconventional-asymmetric doctrine of sea denial.

We suggest this shift in maritime strategy because of what we termed Taiwan’s deterrence trilemma. At a strategic level, Taiwan must simultaneously accomplish three goals that exist in tension with each other:

- It must counter China’s grey zone challenges, which means Taiwan must project symbolic strength across its airspace and territorial waters;

- It must raise the costs of invasion, which means it needs forces that can prolong any conflict and inflict unacceptable losses on the invaders; and

- It must do both of these things in a resource-constrained environment defined by a general unwillingness to significantly increase defense spending

At least in the near term, a military invasion remains unlikely since the PLA faces a number of obstacles that complicate its ability to mount a successful invasion. Nonetheless, time is on China’s side and Taiwan’s naval doctrine and force posture remain misaligned. Although Taiwan has revised its strategy to emphasize multi-domain, asymmetric deterrence, it remains focused on purchasing high-end, high-capability systems such as the F-35B fighter, Aegis-like destroyers and diesel submarines, the “darlings of their service chiefs.”

We argue that Taiwan should enhance its deterrence posture by adopting a more coherent and holistic approach. Specifically, we recommend that it adopt an elastic denial-in-defense strategy, which will consist of three core elements:

- Accept risk in the grey zone. Grey zone aggression does not constitute an existential threat allowing Taiwan to rebalance its force to maintain “just enough” capability to push back against grey zone challenges, such sufficient naval strength to prevent and intercept unwanted excursions into Taiwanese waters;

- Prioritize denial operations. Specifically, divest as many costly, high-tech platforms as possible so as to invest in large numbers of relatively low-cost, counter-invasion capabilities. This would raise the cost associated with bringing a hostile force close to Taiwan’s shores; and

- Invest in popular resistance. The prospect of waging a prolonged insurgency will likely deter China’s leadership far more than the threat of fighting a relatively small, conventional force.

We are not the first to propose shifting to an asymmetric maritime force to deny China use of the seas as an invasion corridor. Numerous reports and analyses have suggested specific maritime platforms Taiwan should acquire to execute a sea denial strategy, such as fast missile boats, semi-submersibles, mini-submarines, mines, and coastal defense cruise missiles. We entirely agree with these recommendations and note that to date, despite talk of an asymmetric strategy, Taiwan has made only marginal changes. For example, while it has modestly increased its inventory of missile boats and anti-ship cruise missiles, Taiwan’s navy remains anchored around a relatively small and therefore vulnerable inventory of high-end platforms.

The political reality is that Taiwan’s navy faces major resource constraints and so must make difficult choices. Accordingly, Taiwan should defer its high-profile procurement priorities, especially the Aegis-like destroyer and the Indigenous Diesel Submarine (IDS). These are technically challenging programs, especially given Taiwan’s lack of experience building similar platforms. Additionally, they are expensive enough that Taiwan will not be able to field them in large numbers and ultimately remain vulnerable to Chinese long-range strike and anti-access weapons systems. Taiwan’s current naval fleet, although aged, is sufficient to “show the flag” and resist grey-zone aggression for the near future. Instead of these planned procurements, Taiwan should significantly increase the numbers of low-cost, lethal platforms, even at the expense of other planned procurements.

These lower cost platforms, by the larger numbers procured, complicate adversary targeting and improve their force-level survivability against PLA strike capabilities. Taiwan should start by fielding a larger fleet than currently envisioned of its stealthy Tuo Jiang missile corvette and build on the lessons learned from these small corvettes to field a future small frigate. Both can fulfill peacetime missions but be built in large enough numbers to possibly survive in a wartime environment. By delaying the more ambitious destroyer and IDS programs and starting with smaller, less expensive projects, Taiwan can best prioritize limited resources.

This incremental approach also helps develop relevant technical capability, so that potential future submarine and large surface combatant programs are less technically risky when it becomes fiscally and strategically appropriate to build them. The immediate savings from delaying the destroyer and IDS programs can be diverted into the sea denial platforms that Taiwan needs now, ranging from the small frigate discussed above to even smaller missile boats, mini-subs and mobile anti-ship cruise missiles.

Moreover, Taiwan should eliminate its entire amphibious force. Bluntly speaking, Taiwan’s amphibious assault ships are strategically unnecessary as they are not immediately useful for confronting limited challenges to Taiwan’s territorial sovereignty or other “grey zone” aggression. They also have no ability to counter a cross-strait invasion. Rather than procure expensive amphibious assault ships and maintain aging landing craft, which generate sizable sustainment costs, Taiwan should retire this entire force. It can then shift these savings into further investments in counter-invasion capabilities.

Because Taiwan’s Marine Corps would be losing its sealift, it should be rebranded as Taiwan’s premier counter-amphibious force so as to fill a gap between the navy’s sea denial role and the army’s ground denial mission. Specifically, it would specialize in defending possible landing zones with mines and spread out hard points in addition to engaging landing craft with dispersed, near-shore weapons such as anti-tank guided missiles.

These proposals to transform Taiwan’s naval strategy and procurement plans would produce a force capable of waging a sea denial campaign against a conventionally superior opponent, tailored to the specific threat of a cross-Strait invasion. The changes in naval force structure would be mirrored throughout Taiwan’s armed forces, to include a reduction in army ground strength, the termination of plans to procure F-35B fighters, and accelerated procurement of similar asymmetric capabilities. To invest in popular resistance, we recommend transforming Taiwan’s two-million-man Reserve Force into a Territorial Defense Force prepared to conduct a lengthy insurgency campaign. By abandoning plans for a decisive battle and shifting to a posture that increases invasion costs and prevents a quick victory, Taiwan can better deter China.

Read about these recommendations and more in the full report: A Question of Time: Enhancing Taiwan’s Conventional Deterrence Posture.

Joe Petrucelli is a Ph.D. student at George Mason University’s Schar School of Policy and Government and a currently mobilized U.S. Navy reserve officer. The analysis and opinions expressed here are his alone and they do not represent those of the Department of Defense.

Featured Image: Tuo Jiang-class missile boat in service with the Taiwanese Navy. (Defense Ministry of Taiwan)