By Ridvan Bari Urcosta

Introduction

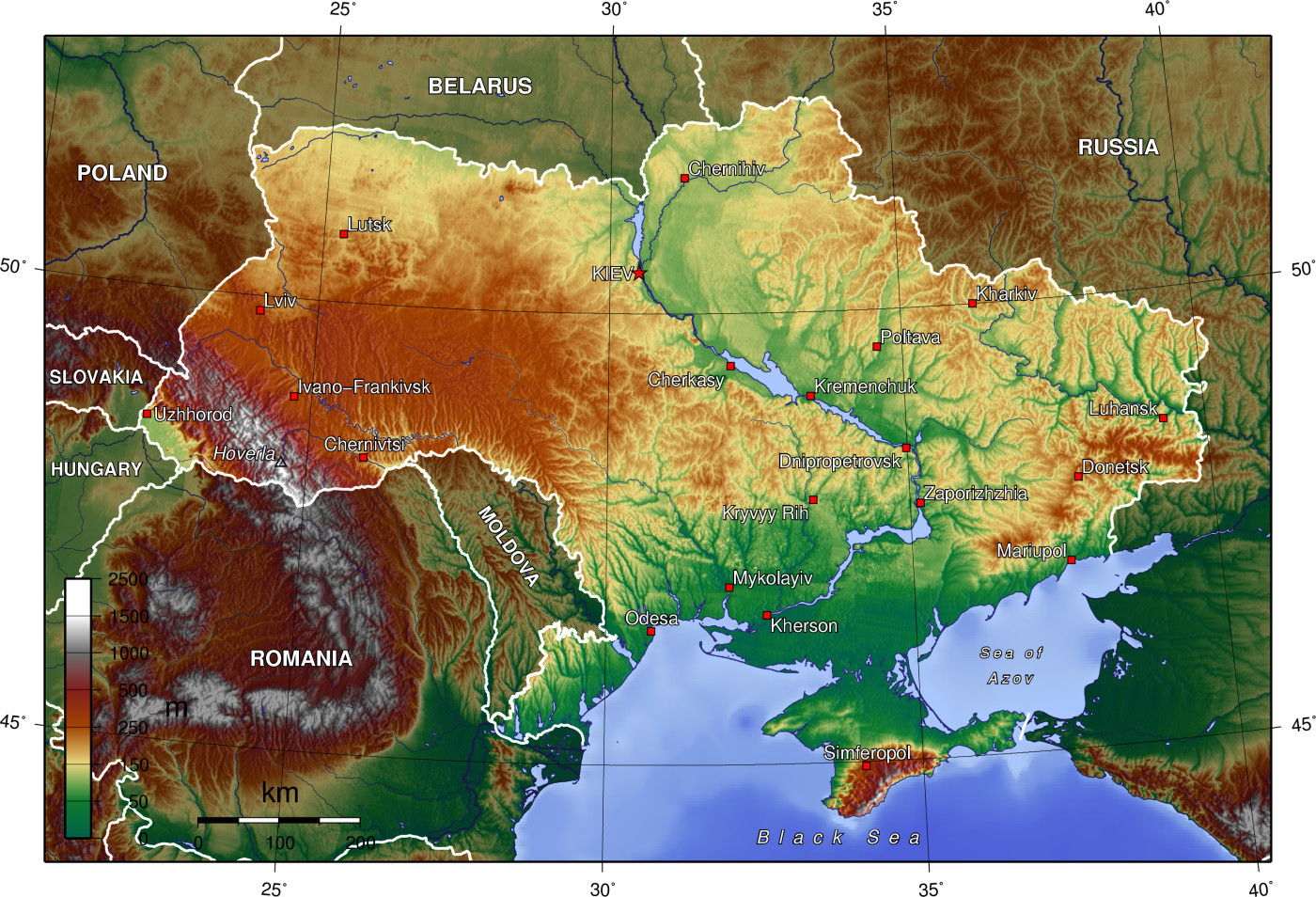

The Sea of Azov is a tiny and small sea that historically has not often earned much strategic attention from the countries that possessed it. However, history reveals that the strategic importance of the sea periodically rises when at least two countries possess the shores of this sea. The sea lends itself to regional geopolitical rivalry, and as a result of tensions both sides often create Azov flotillas. Such a contest existed during the Civil War in Russia and the Second World War when both the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany had to establish special naval units in the Sea of Azov. In general, Russia’s historical expansion to the South had three main directions – the Northern Caucasus, the Sea of Azov, and Crimea. All of these three geographical directions are fully interrelated. First, the Russian Azov Flotilla appeared in 1768 in order to fight the Crimean Tatars and Ottoman Empire. Now the geopolitical situation again necessitates that both Kiev and Moscow urgently create Azovian geographical units drawn from their naval forces.

Since the annexation of Crimea in 2014, the Russian Federation became a full-fledged hegemon in the Azov Sea because of how the annexation of Crimea greatly expanded Russian coastal possessions. The Kerch Straits made Russia the keeper of a strategic chokepoint where the Kerch Strait acts as a gate to free waters and to Ukrainian and Russian Azovian ports. Interestingly, Russian river waterways facilitate a connection between the Black Sea with Russian cities that are almost located in Siberia and even deliver goods directly to Moscow or to the Baltics. In these regards, the possession of the Kerch Strait and access to the Sea of Azov has strategic meaning to Russia. As tensions have been building in recent months in the Sea of Azov Russia and Ukraine find themselves poised for further escalation.

Russian Naval and Maritime Strategy in the Sea of Azov

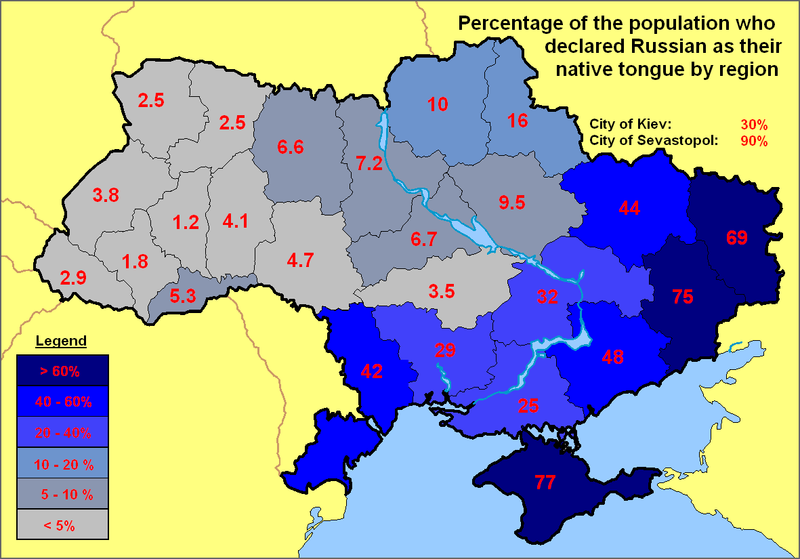

It is crucial to view Russia’s general vision regarding naval strategy and its place in the Sea of Azov since 1991 in order to understand the current state in broader context. Before Vladimir Putin, Russia’s leadership did not pay much attention to the country’s naval forces. But in 2000, the same year Putin came to power, the situation changed. Russia introduced the “Naval Strategy of Russia” in which there was pointed attention from the Kremlin in the Sea of Azov and the Black Sea. Putin personally participated in the drafting of the document. In the document it was clear that these seas, together with the Baltic and Caspian Seas, have serious importance to Russian national interests. With respect to the Sea of Azov Russia had proposed it be labeled as internal waters as the most suitable approach to national interests. Moreover, along with Moscow’s return to the old Soviet Union approach in trying to turn southern seas into “internal seas,” Russia wanted to establish a favored regime that would block every non-Azovian state warship from the entrance into the seas.

Next year in 2001, Russia introduced the “The Russian Maritime Doctrine” where again the Kremlin asserted that the Sea of Azov is a part of national interests. According to the document, the longstanding interests of Russia in the Black and Azov Seas were the restoration of the naval and merchant fleets along with the inland navigation system (Don-Volga canal system), ports, and other infrastructure. It emphasized the necessity of addressing with the Ukrainian government the legal status of the Black Sea Fleet and to ensure that Sevastopol remains the main base of the Fleet. And finally, it discussed the creation of conditions for basing and using the components of maritime potential that would protect the sovereignty as well as international rights of the Russian Federation in the Black and Azov Seas.

Next, the “Naval Strategy of Russia 2020” was issued in 2012 and neither of the seas were mentioned. However, it was clear that some aspects of the document were related to the Sea of Azov and that Russia was facing restrictions to full access to the global maritime domain, and faced disputed maritime claims from neighboring countries. After the alteration of the international environment and due to the annexation of Crimea, Moscow released the “Maritime Doctrine 2020” in 2015, and again paid full attention to the region and categorizes the Black and Azov Sea as a part of the “Atlantic Regional Priority Area.” It highlights the region as crucial for national interests partly because it is proximate to NATO.

Thus, according to the document, the following measures were provided:

- To set more favorable (on the basis of the international law) international regimes for Russia in the Azov and Black Seas

- Systems of using natural resources of these seas

- Free use of the oil and gas fields and construction and operating pipelines

- To set international and legal regulation regimes in the Kerch Strait

- To enhance and to improve the structure and naval bases of the Black Sea Fleet and the development of its infrastructure in Crimea and Krasnodar Kray

- Building the related vessels and ships, especially river-sea type, and development of port infrastructure in these seas

- Creation of three huge regional economic and maritime zones (centers): Crimean, Black Sea-Kuban, and Azovian-Don zones

- Further development in regional gas and oil pipeline systems. (For instance, according to the Ministry of Energy, in the production structure of the Russian Federation the share of offshore fields in the Azov Sea is 9.4 percent of Russian oil and 14.7 percent of gas.)

- To provide a direct logistical connection between the Crimean peninsula and Krasnodar Kray. (Here at the moment of adoption of the document, it still was a theoretical scenario for a direct land connection through the territory of Ukraine, but now the recently completed Kerch Bridge has become the sole option.)

- Exploration of minerals in the seas

On July 20, 2017 Putin signed “The fundamentals of the state policy of the Russian Federation in the field of naval policy for the period up to 2030.” Again, previously mentioned threats were indicated, but the language of the document changed gravely in that it became more antagonistic and aggressive. The Azov Sea was mentioned regarding the necessity of maintaining favorable legal regimes around the state border of the Russian Federation, the border area, in the exclusive economic zone, on the continental shelf, as well as in the waters of the Caspian and Azov Seas. Without the Crimean peninsula it is impossible to fully appreciate the security implications for Russia’s policy in the Azov Sea. In Crimea, according to the document, it was recommended that Russia pursue an increase of the operational and combat capabilities of the Black Sea Fleet by developing an interspecific grouping of forces on the territory of the Crimean peninsula.

A historic moment that sheds light on Russia’s strategic vision in the Sea of Azov is the Yeysk meeting in 2003. The Tuzla Island conflict started on September 29, 2003 when Russia initiated the construction of an artificial dam on the tiny island within the Kerch Strait, and the Yeysk meeting was conducted under Vladimir Putin’s supervision on September 17, 2003. On the same day before Yeysk, he had met with Ukrainian President Leonid Kuchma where he clearly stressed that “the Sea of Azov must be the internal sea of Russia and Ukraine.” Already in Yeysk (an important Russian city on the Azov shores with heavy military presence), Putin held a historical meeting for Russian geopolitical ambitions in its southern region. All the most important ministers responsible for the state military, naval, and security policy were present.

During the meeting, Putin made strong commitments regarding the Black and Azov Seas. At the onset of the meeting he said:

“I would like to talk about the Azov-Black Sea basin as a whole. On military and environmental issues it is a zone that is very important for Russia. This is the zone of our strategic interests. The Black Sea region has a special geopolitical significance. The Black Sea provides Russia’s direct access to the most important global transport routes, including energy.”

In this phrase he outlined the key interests of Russia in this region without which Russian national interests could not be fulfilled. In order to impart this vision in the formal framework, Putin signed the document “Plan of cooperation of ministries and agencies to address the diplomatic and military missions in the Azov-Black Sea region.” The text of the plan was closed from publicity but its general aim was to provide a complex strategy of Russia to this Black-Azov Seas region and the modernization of port and naval facilities. The next point which was raised is the Azov Sea question; according to Putin, it is undergoing a difficult process of negotiations and painstaking efforts to resolve existing problems of the legal status of the borders, regimes of straits, and legal aspects of the use of the water area and resources of the Black and Azov Seas. Moreover, within the meeting he signed a decree “On the establishment of the Black Sea Fleet’s base in Novorossiysk.” Many western and Ukrainian experts and politicians regarded it as a retreat of Russia in the means of her ambitions in the region, but Putin directly stressed that it is not a sign of retreat and that Sevastopol will remain a main base of the Russian Black Sea Fleet. Furthermore, during the meeting Putin emphasized the crucial reason why the Kremlin did not pay attention to the Azov Sea because “For a long time, a large number of ministries and departments were focused on the Caspian Sea. I think that now it is time to come to grips with the problems of the Azov-Black Sea basin.”

A Longstanding Dispute

Negotiations regarding the status of the Sea of Azov and the Kerch Strait began in 1995, and Russia steadily avoided finalizing them on Ukrainian terms. Only after the Tuzla Island crisis in September 2003 did Ukraine and Russia finally sign the agreement in December of the same year. At the same time, the biggest political disaster that Russia faced as a result of Tuzla crisis was the consolidation and hardening of the Ukrainian nation toward Russia. The Tuzla events were partly preconditions for the Orange Revolution in 2004. For the first time in many years it posed the possibility of a direct confrontation between the two nations.

After the Orange Revolution in 2004 new political leadership in Kiev called for a revision of this agreement and considered it a deal that had been imposed on Ukraine by the use of political and diplomatic pressure. Since then, negotiations were conducted many times but Ukranian President Viktor Yushchenko could not manage to settle the issue on Ukrainian terms. It should be taken into account that even the 2003 agreement did not satisfy Moscow, but it was definitely a victory for Moscow after years of contention. Ukraine was holding the largest and richest share of fish zones in the Sea of Azov and had total control of the Kerch-Enikale Canal. But for Russia, it secured the Sea of Azov from any possibility of foreign warships entering the sea, and Russia earned the ability to use the Kerch-Enikale Canal freely. Before, Russian vessels had to pay Ukraine for passage in and out of the Kerch Strait. Finally, the signed treaty that ended the dispute had a positive impact on Russia because Ukraine was forced to recognize the Sea of Azov as an internal sea. Thus the sea was sealed from third-party countries.

Unfortunately, Ukraine in 2003 did not effectively use international law and the influence of the West in order to settle the issue with Russia. NATO behaved in a very tempered manner and avoided taking sides. Ukrainian President Kuchma publicly asked the General Secretary of the NATO Lord George Robertson for an intervention into the confrontation before his departing to Moscow. Moreover, the head of the foreign office of the EU presented almost the same position of NATO and EU when he said the conflict “will be resolved and defused among themselves.” In 2010 when the regime of Yanukovich came to power, Russia made the status of Sevastopol a priority (the Kharkov Agreement), but negotiations about the Kerch Strait and the Sea of Azov never stopped because Russia wanted further expansion. Particularly in terms of favorable regimes, in the Kerch Strait they proposed the creation of a joint venture that would operate in the Strait. In 2013, Putin officially returned to the Sea of Azov question but he never returned to this topic very publicly. Even since the annexation of Crimea, he delegated the issue while he was silent about it himself. After the Maidan Revolution, the new Ukrainian political elite confronted the agreement but did not manage to revise it.

According to the 2003 agreement, Ukraine has legal control over 62 percent of Sea of Azov’s area and Russia only 38 percent, but since the annexation of Crimea, Russia possesses de facto three-quarters of the territory of the sea. It tries to impose this fact in relations with Ukraine. Plus, Russian proxies are possessing additional territories in the East of Ukraine that plays on Russian advances. The whole coastline of the breakaway Donetsk People’s Republic is approximately 45 km. In their territories, there are plans to erect a naval base in the Obryw village. It is more likely that Russia will be denying its involvement in the creation of the base. Therefore, in the Sea of Azov there are three major established naval centers in the zones of control under Ukraine, Russia, and the separatist republic of DPR.

Additionally, a great hindrance to the free navigation of international and Ukrainian ships was incurred with the opening of the Kerch Bridge in May. The bridge has an air draught of 33 meters and a water draught of eight meters which restricts the entrance of larger ships into the Sea of Azov. Notwithstanding the fact that Ukraine is reportedly eager to denounce the 2003 Agreement, Russia could go even further unilaterally – eventually sealing the free passage in the Kerch Strait to the Ukrainian merchant fleet. In this scenario Ukraine could have to pay for passage as Russia did before 2003.

The Sea of Azov after 2014 was more or less a tranquil place compared to the Donbas and Crimea, but the completion of the first phase of the Kerch Bridge required more decisive measures from Russia. Additionally, an incident with a boat arrested by Ukraine further escalated the situation. The Russian Federation still demands that Kiev return the boat and the captain as a main condition for returning to the status quo. Russia continues to use the following measures against Ukraine:

- Increasing the time for permit issues for the passing to and from the Azov Sea

- Undertaking additional controls of the vessels in the Azov Sea water going to Ukrainian ports and “luckily” facing one more control when they return after shipment

- Russia is challenging Ukrainian naval forces when controls are happening very close to Ukrainian shores

- Pushing Ukrainian fisheries to avoid going to sea

- Since June until October, Russia inspected 171 vessels and it took on average three days

- Ukrainian and Georgian vessels undergo more detailed inspections

- Usually 10 Russian warships are patrolling the Sea of Azov and Moscow sometimes closes parts of the sea under the pretext of naval drills

The Ukrainian economic losses to date are obvious. For instance, only from January to July Ukraine lost 50 percent of fishing, 30 percent of the profit of ports, and most importantly, the share of the ports in metallurgical export deteriorated to 50 percent. This trend will only be broadening and it is even possible to say that in the long-term Russia may attempt to eventually halt commercial activities. This could lead to social and political protests against the current political elite in Kiev if the situation does not change. Furthermore, Russia has plans to extract and use Ukrainian and Crimean Tatar natural resources from Crimea and the Sea of Azov such as the Azov-Berezansky and Indolo-Kubnasky oil and gas fields. Estimated oil and gas deposits in the Sea of Azov are 413 million tons. As a result of the Ukrainian water blockade of Crimea, Moscow may also be desperately seeking the fresh water in the Sea of Azov.

Russia caught Kiev in three main geopolitical traps. First, if Ukraine is going to confront Russia and demonstrate principality in the Azov sea, she should take into account that economic and social deterioration will become a direct consequence of this confrontation. Even though Ukraine goes to a stiff political stance in confronting Russia, international maritime companies will be avoiding this region and will try to find alternative routes. It should be noted that a quite popular idea with Russia is that of mining the Ukrainian coastline. Definitely these kinds of measures do not attract foreign investments. Second, Ukrainian naval forces are incomparable with Russian forces. Moscow is the absolute naval hegemon in this sea. Third, it is a “denunciation” trap. In Ukraine, denunciation is quite popular but some voices are against the argument that Ukraine will be deprived of a free passage through the Kerch Strait for the Ukrainian merchant fleet.

Western Responses and Countermeasures

The Ukrainian answer is offered by several measures. First, is a “law binding” policy. In 2016 Ukraine filed a lawsuit against the Russian Federation to the Permanent Court of Arbitrations – “Dispute Concerning Coastal State Rights in the Black Sea, Sea of Azov and Kerch Strait (Ukraine vs. the Russian Federation).” Interestingly, Russia is actively engaging in the process. Second, it is the establishment of sufficient naval forces (an “Azov flotilla”) by using external and internal sources for naval enforcement – for instance, building additional gunboats “Gurza-M” (Project 58155). For instance, Capitan Andriy Ryzenko presented a strategy of a “Mosquitoes Fleet” as the best option to counter Russia expansion in the sea. Currently, NATO and Ukrainian specialists are engaged in preparation of the “Naval Strategy 2035” that will take into consideration the recent developments in the Sea of Azov. Ukraine is considering the possibility of convoying Ukrainian and European vessels into the Sea of Azov. Additionally some Ukrainian politicians are voicing the necessity of sanctioning Russian ports in the Black and Azov seas for Russia’s unlawful activities and to develop the coastal missile defense systems that could deter Russia from direct invasion of Mariupol and Berdyansk.

Western reaction to the developments in the Sea of Azov have not been prompt since the recent confrontation began in March 2018. On August 30, the U.S State Department issued a press statement “Russia’s Harassment of the International Shipping Transiting the Kerch Strait and Sea of Azov.” The State Department called on Russia to cease its harassment of international shipping. On October 24, the General Secretary of NATO Jens Stoltenberg stressed during a press conference NATO’s concern regarding the situation in the Sea of Azov and about importance of the freedom of navigation both for Ukrainian and NATO ships in this sea. Interestingly, on October 31 there was a regular official meeting of the NATO-Russia Council in Brussels where according to the press release both sides discussed the situation in Ukraine and the escalation in the Sea of Azov but without any public details.

In Brussels, already in the middle of summer there were some discussions regarding the situation in the Sea of Azov. For example, on October 9, the European Policy Center conducted the event “Occupied Crimea: The impact on human rights and security in the Black and Azov Seas” that has been dedicated particularly to the recent escalation in the region. Representatives of the European Parliament, Ukrainian Ministers, experts and former NATO officials took part in the event. In the European Parliament of Subcommittee on the Security and Defense (SEDE) a very effective hearing was held with a fruitful discussion and provided analytical grounds for the European Parliament’s Resolution. Additionally, the Chair of the SEDE, Anna Fotyga, together with the other MPs, visited the east of Ukraine on 16-20 September where they observed the security situation in the contact-line in Donbas and in the city of Mariupol. In the SEDE hearings on October 11, “On the Security Situation in the Azov Sea” in the EP there were officials from the European External Action Service responsible for the Eastern dimension of the EU foreign policy, including Ambassador Konstiantyn Yelisieiev who is now the Deputy Head of Presidential Administration to the President of Ukraine and NATO’s officials.

Ms. Fotyga stressed that the Russian approach toward the seas has some similarities and they are to be found even in the Baltic region, where Russia is using its geographical advantage over Poland in the Vistula Lagoon and Strait of Baltiysk. Russia, as she stressed, is seeking ways to establish internal lakes (with limited access) in those seas. The representative of the EEAS stated that in July the EU imposed individual sanctions against persons involved in the Kerch Bridge construction and condemned the deterioration of the situation in the Black and Azov Seas. Mr. Yelisieiev presented a comprehensive and full picture of aggressive Russian behavior not only in the Sea of Azov but also in Crimea and the Black Sea. According to him, Russia pursues the following aims:

- A land corridor to Crimea

- Militarization of the Sea of Azov thereby to outflank Ukrainian military positions in the East of Ukraine

- Social and economic destabilization of the region

- Total control over the Black and Azov Seas in order to have secure flanks for further expansion

At the same time Yelisieiev outlined the necessity of the technical and economic assistance to Mariupol and Berdyansk. Moreover, on behalf of Ukrainian government, he was asking for the extension of sanctions against southern ports of Russia. As he noted “lack of the common response instigates the aggressor’s appetite.” He reiterated that the best option to deter Russia is to be braver in Ukraine and to finalize the membership action plan.

NATO representative Radoslava Stefanova, Head of the Russia and Ukraine Section, Political Affairs and Security Policy Division, stated that the case of the Sea of Azov is a much broader problem that is happening in the southern flank of the NATO. Three littoral states have access to the Black Sea together with strategic partners (Ukraine and Georgia) and since the Warsaw Summit NATO is trying to establish stronger presence in this region. During the last year and a half, NATO is actively involved in the assistance of the reconstruction of Ukrainian naval and maritime capability and the associated training. NATO, according to Ms. Stefanova, has reinforced the staff in Kiev and especially to those fields that are related to security and defense, and even sent to Kiev more experts to prepare a Ukrainian naval strategy.

Another event of interest is the Plenary Session in Strasbourg on October 23 “On the Situation in the Sea of Azov” together with the Vice-President of the Commission Federica Mogherini. In her speech, she outlined that the EU is concerned about the situation in the sea and its militarization and reiterated the EU’s support to Ukraine. She emphasized that militarization of the sea is threatening to undermine the wider Black Sea region and this is in no one’s interests. What is also of note is that she said that the Black Sea is a European sea – an idea that is not welcomed in Russia and is considered aggressive. In general, the discussion during the plenary session demonstrated full commitment and almost absolute majority to support Ukrainian sovereignty and asked for further development of sanctions against the Russian Federation.

The resolution adopted on October 24 appears to demonstrate that the European Parliament is firmly committed to reacting to emerging threats in this neighborhood. The resolution goes through crucial details of the confrontation and touches on the problem of the militarization of the Crimean peninsula and Sea of Azov as intertwined cases. Among its contents it also:

- Condemns Russian violation of the freedom of navigation and construction of the Kerch Bridge

- Highlights Russia’s plans to extract natural resources (oil and gas resources) from the legal Ukrainian territories

- Goes through the unacceptability of such a policy not only in the Sea of Azov but in the Vistula Lagoon (Poland)

- Calls for a more comprehensive EU foreign policy in this region and to appoint an EU Special Envoy to Donbas, Crimea, and the Sea of Azov

- Underlines the necessity to send mission experts to Mariupol that will be assessing the damage to the region and look at alternative ways of maintaining regional, social, and economic sustainability.

Regarding the recent escalation in the Black Sea zone of the Kerch Strait the western reaction was again quite restrained. The U.S State Department issued a statement indicating that they are concerned with the dangerous escalation in the Kerch Strait and that it “condemns this aggressive Russian action.” Washington again called for both parties to “exercise restraint and abide by their international obligations and commitments. We urge Presidents Poroshenko and Putin to engage directly to resolve this situation.” It is possible to assume that such a vague statement holds little water with Ukraine. Something similar happened with the European Union’s reaction where it defined the situation as dangerous and called on both sides to exercise “utmost restraint” and called for de-escalation. The Turkish Republic also called for the peaceful resolution of the confrontation, and the Turkish Foreign Affairs Ministry stated that it is concerned that Ukrainian vessels were fired upon but it does not make any reference to Russia. Even so, Ukraine together with its allies, managed to conduct an emergency meeting at the UN Security Council but it did not had desired effect. The most lackluster reaction was the aftermath of the private meeting of the Political and Security Committee in Brussels that refrained to go tougher against the Russian Federation.

Thus we could see that the consequences of the incident remain unclear. The international reaction demonstrates to Kiev that it is not ready to escalate the situation. At the same time, it is more likely that both the European Union and the United States are going to provide more measures to deter Russian hegemony in the Sea of Azov and Black Sea.

Conclusion

History rarely pays attention to the Sea of Azov, but it is always related to the strategic importance of Crimea. When the Russian Federation annexed the Crimean peninsula and further consolidated its military facilities, it became clear that the Sea of Azov will again be playing an important strategic role in East-West relations. After more than 20 years of strategic patience Russia resolved many of its longstanding problems about the Azov and Black Sea regions by annexing Crimea. It is not a mere coincidence when the Foreign Minister of Russia, Sergey Lavrov, on March 21, 2014 straightforwardly pointed out that since the annexation, the Kerch Strait “could not be the subject of negotiations anymore.”

Almost five years after the annexation of the Crimean peninsula it appears that Russia is again trying to impose a long-term strategy to deal a crucial blow in Ukraine via the Sea of Azov. In Moscow they count on strategic patience, and as Putin said “in long-run strategy we must win.” Western answers and reactions have to be strong and preventative. The case of the adopted EU resolution is direct evidence of how interested Western commitments are. But if the recommendations in the resolution remain on paper it means that aggressive Russian behavior is poised to deal another blow to Ukraine and the West.

Ridvan Bari Urcosta is a research fellow at the Center of Strategic Studies, University of Warsaw.

Featured Image: Kerch bridge. (Wikimedia Commons)