By CDR Luis Nuno Sardinha Monteiro, Portuguese Navy, for our Forgotten Naval Strategists Week

“Good war makes good peace”

In “Art of War at Sea” (Part I, Chapter 1)

Introduction

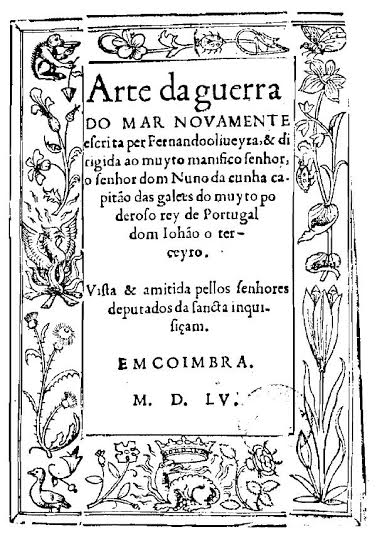

The Discoveries Era, a period of expansive exploration initiated by Portuguese navigators, prompted the emergence of a structured naval thinking in the 16th century. This originated mainly in the Mediterranean countries (specifically France, Italy, Portugal and Spain). Among the works produced at that time stands out a treatise written in 1555 by Portuguese Priest Fernando Oliveira, entitled “Arte da Guerra do Mar” (“Art of War at Sea”). It addresses, in a truly comprehensive and integrated way, a wide range of nautical and naval warfare issues, but it goes beyond a mere tactical and operational perspective, revealing a strategic vision with regard to the engagement of navies at the service of national interests, as well as other innovative strategic insights.

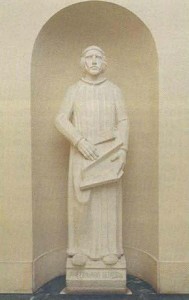

Life

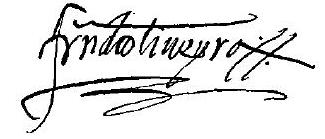

Fernando Oliveira was born circa 1507 and at the age of 10 entered a Dominican Convent, where he acquired the humanist values manifested in his writings. In 1536, he published a grammar of the Portuguese language. This was his first book and also the first Portuguese grammar ever published.

Oliveira was a venturesome man, with a profound love of seafaring. Therefore, he took every opportunity to get underway, be the ships Portuguese, French, English or Spanish. Sometimes Oliveira volunteered as chaplain, but most of the time he was hired as pilot, due to his extensive knowledge and experience of nautical sciences. Every now and then these ships engaged in naval combat and he was even taken prisoner on several occasions.

Oliveira parlayed his vast experience at sea to produce seminal treatises on nautical and naval warfare issues. Besides the already mentioned treatise “Art of War at Sea” (published in 1555), he also wrote:

- An encyclopedic treatise dated circa 1570 and entitled “Ars Nautica” (“Art of Navigation”). This work was written in Latin and has three parts: one about navigation, another about naval construction (the first known scientific work on this topic), and a third addressing generic navies’ logistical and administrative matters;

- A companion work on naval construction, written around 1580 in Portuguese and entitled “Livro da Fábrica das Naus” (“Book on the Building of Ships”);

- A book entitled “História de Portugal” (“History of Portugal”), written probably in 1581.

With regard to naval strategy, Oliveira’s keystone work is “Art of War at Sea”, which is therefore the main subject of this text and from which all citations contained in this article have been taken.

“Art of War at Sea”

“Art of War at Sea” has one prologue and two parts, each of them containing fifteen chapters. It addresses a broad array of topics, such as naval construction, ship’s commissioning, navigation, seamanship, meteorology, oceanography, logistics, recruitment, training, education, command skills, maritime ceremonial and intelligence.

“Art of War at Sea” has one prologue and two parts, each of them containing fifteen chapters. It addresses a broad array of topics, such as naval construction, ship’s commissioning, navigation, seamanship, meteorology, oceanography, logistics, recruitment, training, education, command skills, maritime ceremonial and intelligence.

To illustrate his ideas, Oliveira often recalls warfare episodes from the Classical Era (ancient Greece and Rome) and from the Discoveries Era (with a focus on episodes of the Portuguese history).

In Chapter 14 of Part II, Oliveira lists 39 “general rules of war” that summarize and synthetize most of the issues covered in the book. These are very simple aphorisms, such as “better order than multitude” (stressing the value of military organization) and “war requires fairness and deceit, truth and lie, cruelty and pity, preserving and destroying” (noting the contradictory nature of war).

There is only one copy of the original treatise, which is at the National Library of Portugal, in Lisbon. However, the book has been republished four times: in 1937, 1969, 1983 and 2008. The most recent editions include a facsimile of the original 1555 edition.

Influences in “Art of War at Sea”

Oliveira was an erudite and cultivated person, who was inspired by the classical authors, as was characteristic in the Renaissance. His main reference for “Art of War at Sea” was the Roman writer of the 4th century Publius Flavius Vegetius Renatus, commonly referred to simply as Vegetius. Vegetius wrote “De Re Militari” (“Concerning Military Matters”), a treatise about warfare and military principles, which explained methods and practices used during the Roman Empire. In “Art of War at Sea”, Oliveira mentions Vegetius twenty eight times, and one of his most well-known maxims (“If you search peace, study war”) seems directly derived from Vegetius’ dictum “Qui desiderat pacem, praeparet bellum” (“He who desires peace, prepare for war”).

The other main influence in “Art of War at Sea” is St. Augustine, who lived in the 4th and 5th centuries. St. Augustine was a notable theologian and philosopher, who – among other seminal contributions to western Christianity and philosophy – helped crafting the “just war” theory. According to St. Augustine, Christians should be, by the very nature of their faith, against war. However, he considered that the pursuit of peace should always include the option of going to war (a “just war”) if that was the only option to prevent a grave wrong. Oliveira, as a man of the Catholic Church, also believed firmly in “just wars” and dedicated a whole chapter to this issue. Invoking St. Augustine, he defines “just war” as “the one that defends a people from those who want to offend it without reason or the war that punishes the offenses to God” (Chapter 4, Part I). He also considered that “the war of Christians that fear God is not bad, it is full of virtues, because it is done with a desire for peace, without greediness nor cruelty, as a punishment to the bad and relief of the good” (Prologue).

Strategic Thinking

“Art of War at Sea” reveals a reflection upon the importance of naval power as the key to maintaining a mighty empire, such as the Portuguese, with territories and possessions in all five continents.

In the 16th century, the concept of “naval power” had not been introduced. Nevertheless, a careful reading of “Art of War at Sea” shows that Oliveira used the expression “war at sea” with a meaning that encompasses all the aspects of military organization for sea warfare, including construction, commissioning, training and operation of warships, i.e. very similar to what would later be defined as “naval power”.

In the prologue, Oliveira emphasizes the importance of “war at sea” (i.e. “naval power”):

“In particular for this land’s men, that now use the sea more than any others, thus acquiring high profit and honor. (…) Nurturing this war [i.e. this power], Portuguese people have gained lots of wealth & prosperity (…) & have gained honor in a short period of time, as no other nation in longer periods” (Prologue).

In the 3rd chapter, Oliveira returns to this idea that nations must defend their interests at sea through the use of naval power. He emphasizes that maritime security must not be taken for granted, reiterating the importance of naval power to preserve political and economic interests:

“Because the sea is very licentious (sic) and men cannot avoid using it to trade, to fish and to other purposes, taking supply and profit from it, it is essential to safeguard it, through fear or severe punishment. (….) Due to all these reasons, it is necessary to have navies at sea, that safe keep our coasts and passages and that protect from the surprises that can storm from the sea, which are much more sudden than the ones coming from land” (Chapter 3, Part I).

In addition, I would like to briefly present some of the perennial strategic principles than can be found in Oliveira’s work and illustrate each of them with a citation from “Art of War at Sea”.

- Importance of readiness at sea: “Promptitude gives victory to the diligent and negligence defeats the careless”.

- Importance of the surprise factor: “Sudden attacks terrify the enemies, but expected encounters do not frighten them”.

- Time as a fundamental element of strategy: “There is a time to engage in battle, when we have an opportunity or when the advantage is on our side”.

- Space as a fundamental element of strategy: “The location is often worthier than the force”.

- Importance of deception: “Let us dissimulate as much as we can, so that we will be taken as liars”.

- Importance of intelligence: “As important as covering our intentions, is trying to know the opponent’s”.

- Importance of unity of command: “It is necessary that man of war have a head (…) and one that commands over everyone”.

Finally, another characteristic of Oliveira’s thinking was his backing of the use of naval power for spreading Christianity. In fact, he praised the Portuguese Discoveries as to “allow multiplying the God’s faith & the salvation of men” (Prologue).

Conclusion

Although written more than 450 years ago, Oliveira’s “Art of War at Sea” is a very comprehensive work, addressing the various elements related to the building up, organization and employment of naval power. Oliveira sought inspiration in the doctrines of Classical authors and in the philosophy of Church thinkers, innovating in the conceptualization of the use of naval power as an instrument to serve the political goals and the economic interests of his country. He was a man ahead of his time, establishing some of the basis of modern naval strategy.

Father Fernando Oliveira anticipated notable strategists such as Alfred Thayer Mahan, who (350 years later) brilliantly theorized about the influence of sea power upon history and its importance, to enhance nations’ wealth and prestige. It is interesting to note two other similarities between Oliveira and Mahan: (1) both resorted extensively to history, choosing specific episodes to illustrate their ideas; (2) both were very religious Christians (although Oliveira was Catholic and Mahan Protestant), having views consistent with the theories of “just war” and advocating the use of naval / sea power to disseminate Christianity.

Unfortunately, “Art of War at Sea” did not have the international projection it deserved and Oliveira remains an obscurity. That can be partially explained because his treatise was written in ancient Portuguese and was never translated to another language. Hopefully, that shortfall is about to be overcome, since my countryman Tiago Maurício is currently translating Father Fernando Oliveira´s “Art of War at Sea” to English. This may allow that treatise getting the attention it deserves, due to its historical value, to the broad range of issues addressed and to its strategic insights – much of which are still valid in the 21st century.

Luís Nuno Sardinha Monteiro is a Commander of the Portuguese Navy. He was Commanding Officer of the fast patrol craft “Dragão” (1992-1994) and of the Portuguese sail training ship “Sagres” (2011-2013). He holds a MSc and a PhD in Navigation Technology, both from the University of Nottingham (UK). He published several books and papers on navigation and naval / maritime strategy. He is currently serving at NATO’s Allied Command Transformation, in Norfolfk (USA).