Tanmen Militia’s Leading Role in the 2014 Haiyang Shiyou (HYSY)-981 Oil Rig Standoff, Spratly Features Construction, and Beyond

By Conor M. Kennedy and Andrew S. Erickson

Our series on the leading maritime militias of Hainan Province continues with this second installment in a two-part in-depth examination of the maritime militia of Tanmen Township. Since its founding in 1985, this force has transformed from an entrepreneurial fishing collective on China’s marine frontier to a reliable frontline unit in increasingly vigorous sovereignty promotion. In part one we discussed the role Tanmen’s maritime militia played in the 2012 Scarborough Shoal Incident that resulted in a Chinese takeover of the feature from the Philippines. After the Communist Party of China (CPC) officially declared the new national goal of becoming a maritime power at the 18th National Congress, newly appointed Chinese President Xi Jinping marked the Tanmen Militia unit as the model for emulation in maritime militia building. A subsequent deluge of delegation visits further reinforced the significance of this unit. Part two will focus on other major events involving the Tanmen Maritime Militia, particularly its participation in the 1995 Mischief Reef Incident and China’s sea-based defense of the HYSY-981 oil rig off the southern Paracel islands in 2014 (which also involved the Sanya militia, as the first article in this series discussed) and China’s multi-decade augmentation of its Spratlys outposts. This article will also probe the Tanmen militia’s organization and leadership, the challenges and opportunities associated with its management and motivation, and will raise the possibility that the Tanmen militiamen’s mission at Scarborough Shoal may not yet be finished.

After Xi Jinping’s visit in 2013, Tanmen Township quickly became ground zero in China’s discussion about the future direction of militia work. The township was host to the 2014 National Border and Coastal Defense Work Conference. Additionally, Tanmen People’s Armed Forces Department (PAFD) Head and Maritime Militia Company Commander Zhang Jiantang attended the Fifth National Conference on Border and Coastal Defense Construction Work in Beijing in June 2014. There he received awards on behalf of his company for its bravery in defending China’s maritime sovereignty. One month prior, he and his men were involved in one of the most volatile showdowns between Vietnam and China since their border war in 1979, the Haiyang Shiyou (HYSY)-981 Oil Rig Standoff of 2 May-15 July 2014.

On 6 June 2014, Vietnamese Ministry of National Defense newspaper The People’s Army stated that China was maintaining between 110 and 115 vessels around China National Offshore Oil Corporation’s (CNOOC) HYSY-981 oil rig. This included 35-40 coast guard vessels, 30 transport ships and tugboats, 35-40 “fishing vessels,” and four naval ships. These forces assembled to form what the PRC Ministry of Foreign Affairs referred to in English as a “cordon” around the oil rig, effectively preventing Vietnamese vessels from approaching the platform. For China’s maritime forces it was an escort mission to protect HYSY-981 during its operations. In early May, the Chinese government issued Maritime Notice 14034 warning foreign vessels not to enter within three nautical miles of the location of the rig at these coordinates (15°29’58.0”N 111°12’06.0”E). However, Vietnamese reports state China expanded its cordon radius and would confront approaching vessels 9.5-10 nautical miles out from the rig. It appears that Vietnam’s fishing vessels could not fish near the platform because of heavy Chinese interference, so they opted to fish outside of the Chinese cordoned area to display presence in their “traditional fishing grounds.” They were not safe, however, as vessels from China’s maritime militia sallied forth to repel the Vietnamese vessels, using non-military forces against non-military forces as a deliberate means of preventing escalation. One report describes Chinese fishing vessel Qiongdongfang 11209 (琼东方11209) ramming and sinking Vietnamese fishing vessel No. 90152 during an encounter 17 nautical miles from the rig, where Vietnamese fishing vessels were surrounded by 40 Chinese fishing vessels. Video footage of Qiongdongfang 11209 running down the smaller Vietnamese vessel can be seen below. Moreover, Vietnam’s smaller wooden-hulled fishing vessels were outclassed by China’s larger tonnage steel-hulled fishing vessels.

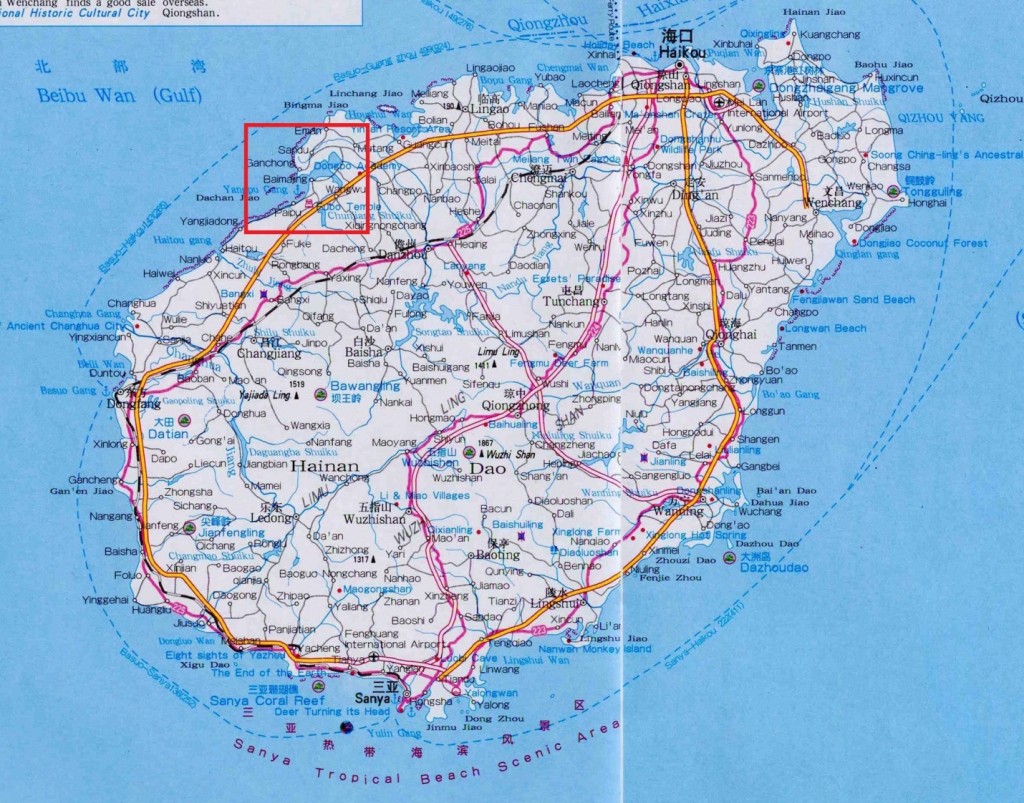

News reports put the number of Chinese vessels present in the area around HYSY-981 at twice that of Vietnam’s. China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs stated that by early June there were as many as 63 Vietnamese vessels in the area. While the number of these vessels present fluctuated over the course of the confrontation, Hainan’s key maritime militia units accounted for many of the Chinese fishing vessels operating on the front lines. Tanmen Maritime Militia Company Deputy Commander Wang Shumao’s web profile on the Qionghai City government website chronicles his force’s mobilization to protect the cordoned zone surrounding HYSY-981 in May 2014. Wang led ten of the company’s militia vessels and 200 militiamen to the platform’s location south of Triton Island to block Vietnamese attempts to disrupt the platform’s operations. Sanya’s maritime militia contributed 29 fishing vessels to the oil rig’s defense. This number, combined with the 10 sent by the Tanmen militia, correlates closely with Vietnamese estimates of the number of Chinese fishing vessels present. While detailed discussion of the fact is beyond this article’s scope, it is clear that maritime militia units from other areas also participated in this incident. The aforementioned Qiongdongfang 11209, for instance, hails from Dongfang City, located on Hainan Province’s western coast between Sanya and Danzhou cities. Dongfang City established its first maritime militia unit on 8 May 2013, with a smaller contingent of 64 fishermen. The sheer scale of the “rights protection” action to defend the cordon around HYSY-981 was surely unprecedented for new units and the more experienced Tanmen maritime militia alike.

In his interviews with the Tanmen fishermen, Zhang Hongzhou of the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies found that although many of the fishing vessels defending the rig were from Tanmen, many fishermen actually did not respond to the Chinese government’s request to mobilize, citing a lack of incentive to do so. To be sure, if a more robust incentive structure were instituted, perhaps a greater number of Chinese fishing vessels would have turned out to completely envelope the oil rig. However, our research indicates that the Tanmen Maritime Militia Company was not simply requested to go, but was ordered to do so—and indeed met its obligations. Local military and government officials likely recognize the difference in reliability between disciplined militia forces and other fishermen and will continue to act accordingly in the future. Furthermore, many Chinese reports on the maritime militia indicate that entry into the militia requires members to submit “National Defense Obligation Registration Certificates” (民兵国防义务登记证) that are reviewed annually. Abandoning one’s duties as a member of the Maritime Militia could result in punishments or in some cases criminal prosecution, according to China’s “Military Service Law,” which specifies rules governing the service of active duty military, People’s Armed Police, and the reserves. Maritime Militia-specific punishments might include fines, withheld fuel subsidies, suspension of trips, or revocation of fishing licenses as described in an article written by the Zhoushan Garrison Commander in Zhejiang Province in 2014. Although it remains unclear to what extent such requirements are actually enforced, militia may respond better to encouragement from local leaders in the form of incentives, whereas overly zealous punishments could dampen the willingness to serve among this amalgamation of irregular volunteers.

Certainly, economic incentives matter in multiple ways. Given overall trends, in which a rising tide of economic growth and government investment may be channeled to raise all boats, officials in key localities of Hainan Province are able to foster maritime militia construction while furthering their other goals. Tanmen Township, for its part, has leveraged its contributions to China’s pursuit of “maritime rights and interests” to expand the scope of its infrastructure and economy. This includes constructing the new Tanmen Bridge to the prosperous Bo’ao Township and developing the clam and turtle industries and tourism. The aim is to transcend exclusive reliance on Tanmen’s fishing industry, while diversifying its services. Still the very picture of a small, sleepy fishing village on the outside, Tanmen has slowly expanded its infrastructure for the fishing industry. Approved by the provincial government, the Tanmen Harbor expansion project broke ground in late August 2006, turning Tanmen fishing harbor into a “core fishing port.” The project entailed dredging out the harbor, greatly expanding the dock space, and expanding shore-side facilities to support the fishing fleets. Through heavy central and local government investment, Tanmen Harbor now reportedly has capacity for one thousand 100-ton fishing vessels. A February 2015 government report put Tanmen’s marine fishing fleet at 786 vessels, with 174 large and medium distant-water vessels and 612 small near-seas vessels. Enjoying great political and financial support, Tanmen harbor is well positioned to support the region’s fishing industry as well as its own burgeoning fishing communities.

Current Force Structure

As with so much else in China, the Party’s leadership role—considered critical to control of the militia and the fishing community more broadly—is central to the Tanmen Militia’s employment in the HYSY-981 incident and to its broader development. To facilitate Party oversight of the Tanmen Militia, a “South China Sea Fisheries Party Branch” was created in 2006 to organize the Party members among the Tanmen fishermen and the vessel owners. The position of Party Chief in this organization is held concurrently by a Tanmen Township Party Committee member. This branch organizes rescue and self-defense training events for the fishermen and implements a system of Party control aboard each fishing vessel. This entails a requirement that there be at least one party member per vessel and the formation of a temporary “Party Small Group” (PSG, 党小组) out of 5-7 vessels that go to sea. These are formed to manage both the fishermen and the militia, ensuring a Party presence for supervising fishermen’s behavior during regular trips out to sea. Each PSG will have a single experienced Party member or vessel captain in command. During Luo Baoming’s 2012 visit to Tanmen Township to inspect the fishing community, he publicly made a radio call at the fisheries management station to one such PSG operating at Johnson South Reef. On the receiving end, PSG leader Shi Kexiong thanked the Central Party enthusiastically for supporting his group’s work. The conversation was a signal to the Tanmen fishermen of the increasing importance of their efforts to advance China’s maritime rights and interests and of the necessity of a Party presence aboard their vessels, even as far away as the Spratlys.

In keeping with China’s parallel Party-State and military structure, Tanmen’s maritime militia members are also directly subject to the PLA chain of command. The principal civilian and military leaders of Tanmen Township, Qionghai City, and Hainan Province are all responsible for militia work within their respective jurisdictions. This dual-responsibility system is at the core of Chinese civil-military integration efforts and ensures ‘Party control of the gun’—in this case, the local military forces including the maritime militia. The Tanmen Maritime Militia is currently led by the Commander Zhang Jiantang (also head of Tanmen PAFD), and Political Instructor Pang Fei, the current Tanmen Township Party Chief. The Tanmen grassroots-level PAFD manages the maritime militia directly and reports back to the Qionghai City county-level PAFD, which is manned by active duty PLA personnel. These PAFDs are at the bottom-tier of the provincial military headquarters system that manages local forces.

The Qionghai City government website description of Tanmen’s involvement in the HYSY-981 incident suggests that on-site authority is delegated to the company’s deputy commander Wang Shumao, who reports back to his superiors in Tanmen. As we previously documented in our article on Sanya City’s maritime militia, the Guangzhou Military Region command mobilized the local forces of the Hainan Military District. It has become clear that a mobilization order also made its way down the chain to the Tanmen PAFD, which then gave its company orders to deploy and defend the HYSY-981 oil rig. While details of the Tanmen Maritime Militia’s specific involvement in that incident remain unclear, the overall process of its participation illuminates how China’s maritime militia is mobilized for maritime rights protection.

Chinese reporting on the Tanmen Maritime Militia varies in its descriptions of the company’s organizational structure. As reported in 2014, Tanmen Maritime Militia units are organized roughly as follows:

Militia Company – Approximately 128 personnel / 12 fishing vessels

Headquarters – 8 personnel

4 Platoons = 12 squads / 10 personnel each

A company of approximately 128 personnel aboard 12 fishing vessels makes up the bulk of the force, with 8 personnel at the maritime militia headquarters. While it is difficult to track the exact composition of any particular unit, Chinese sources help clarify that a single vessel is considered a “squad” and three vessels form a “platoon.” Three platoons composed of nine vessels in total would form a “company.” However, another report in 2013 put the number at 150 personnel and 21 vessels. This suggests a change in the total size of the force over time. The total number of vessels in the militia seems to have shrunk, likely because of the replacement of old wooden-hulled vessels with larger, more capable steel-hulled vessels.

Through various Chinese reports, we have identified the following eleven trawlers as Tanmen Maritime Militia vessels. Their captains typically have specific leadership roles as cadres in the paramilitary organization:

- Qionghai 02048 – Wang Shubiao (Captain) – Platoon Leader

- Qionghai 09045 – Lu Chuan’an (Captain) – Platoon Leader

- Qionghai 03026 – Chen Zebo (Captain) – Platoon Leader

- Qionghai 09099 – Xu Detan (Captain) – Squad Leader

- Qionghai 01066 – Ke Weixiu (Captain) – Squad Leader

- Qionghai 09005 – Lu Quanxiao (Captain)

- Qionghai 02065 – Xiu Guru (Captain)

- Qionghai 02029 – Wang Qingjian (Captain)

- Qionghai 06026 – Huang Hongfen (Captain)

- Qionghai 05033 – Fu Mingguang (Captain)

- Qionghai 09335

On the basis of the organization outlined above, the Tanmen Maritime Militia Company is following a “Maritime Militia Operational Model” that integrates several concepts. The fishing vessels serve as “carriers” or transports (载体), “sovereign islands and reefs” are the “battlefield,” and the home port is the “base.” The company is assigned important roles and missions: displaying a sovereign presence, controlling the marine resources among the islands and reefs, and assisting the troops garrisoned in the South China Sea and assisting maritime agencies in conducting rights protection missions. Tanmen militiamen are also tasked with collecting information on foreign activities in China’s claimed waters and fulfilling other support functions for both the fishing industry and government agencies overall.

Tanmen Militia Training

In 2013, the Tanmen Maritime Militia Company completed 32 days of conventional training and 18 days of high-intensity training. To date, experts from the Sanya Naval base have been invited to train the Tanmen maritime militia twice, focusing on reconnaissance and surveillance skills.

Similar to that for other maritime militia, training will focus on cadres, captains (船老大), and unit leaders, all of whom will in turn provide leadership to individual militiamen on the boats. These personnel, including squad leaders Chen Zebo and Xu Detan (both present at the 2012 Scarborough Shoal standoff), constitute an important “backbone force” in the militia. More politically reliable and experienced than their militia crews, they can exercise leadership over them. This management role is particularly critical, as there may be significant fluctuation in crew composition because the industry relies on Chinese migrant workers who periodically enter and exit the fishing fleet. On 2 February 2013, two months before Xi’s visit, Tanmen Township held a collective training session for such “backbone cadres” in its maritime militia. The session recognized their contribution to protecting maritime rights and sovereignty in 2012 (particularly during the Scarborough Shoal incident) and stressed the role of each cadre as a model representing Tanmen Township, Qionghai City, and Hainan Province. Later that month, Qionghai City held a training event for the Tanmen Maritime Militia Company to plan the year’s training objectives and schedule. Qionghai City Deputy Mayor Fu Chuanfu called for strengthening maritime militia military training to prepare for manifold emergency situations and even high-tech local wars. These meetings, just months before Xi’s visit, were also likely to ensure that the maritime militia members were primed for the political wave about to arrive.

Based inside the Tanmen government compound, the Tanmen Maritime Militia Headquarters is co-located with the People’s Armed Forces Department, which exercises daily command and management of the maritime militia in Tanmen.

Arms and Uniforms

Although Tanmen’s maritime militia do not appear to be regularly armed, they do receive live-fire arms training. In 2013 they held nine live-fire training sessions. Weapons for the Tanmen maritime militia are likely stored in and serviced by the Qionghai City Militia Armory, which is run by the Qionghai City PAFD according to regulations on militia weapons and equipment promulgated by the General Staff Department—now under the responsibility of the newly created National Defense Mobilization Department of the Central Military Commission. Staff responsible for 24-hour management and guarding of the armories are selected from “politically sound” demobilized veterans and they receive salaries and social benefits. Grassroots level PAFDs, like Tanmen, will also have secure weapons rooms, but will likely need to request distribution of the weapons from the Qionghai Armory, as militia weapons and equipment are supposed to be concentrated in the county-level militia armories. If mission requirements call for the Tanmen Militia to be armed, they would need to submit a request up the PLA chain of command for the distribution of weapons. While Tanmen’s maritime militia members are unlikely to be regularly armed at sea, China may, in time, allow its fishermen to defend themselves with light arms. The Hainan Provincial Military District commander major general Zhang Jian wrote in an October 2015 National Defense article that maritime militiamen would receive “defensive combat weaponry” (自卫作战武器) according to their mission.

Tanmen’s “Island” Builders

The origins of the Tanmen Maritime Militia’s status as a uniformed force whose members often work with the PLAN dates to the government-led buildup of the past three decades. Many years prior to that, Tanmen Maritime Militia personnel and regular fishermen took it upon themselves to develop many of South China Sea islands and reefs for their own economic benefit, often landing and camping out on such features. They officially became involved in the state’s development of the Paracels and Spratlys in late 1988 when the then-Deputy Party Secretary of Tanmen accepted the mission after a visit with naval engineers at the PLA Navy’s South Sea Fleet base in Zhanjiang. Upon returning to Tanmen they quickly began selecting the members of the maritime militia and vessels to undertake this effort. Platoon Leader Wang Shumao (today Deputy Company Commander) and several other militia captains were chosen to begin assisting PLA troops in the construction of Chinese-controlled features in the Spratlys, delivering stone, rebar, and concrete. During this period, Tanmen maritime militiamen reportedly made 580 trips to the Spratlys and delivered 2.65 million tons of materials to assist the navy in constructing docks on all seven of the Chinese-occupied Spratly features. They also helped deliver provisions to the troops stationed on those features, alleviating the supply concerns of those responsible for remaining in the harsh conditions of remote island and reef garrisons. Tanmen’s current company commander, Zhang Jiantang, explains that the naval vessels’ draughts were too deep to reach the shallow-water features, so they used Tanmen fishermen aboard fishing vessels and small motorboats to transport building materials to the construction sites. This demonstrates that, at least in the early years of PRC presence in the Spratlys, the Tanmen Militia was a critical enabler of China’s sustained occupation of its features.

Below is a brief timeline describing the construction work of Tanmen Maritime Militia forces on Spratly reefs. Identified by name where possible, some of the fishing vessel captains involved in this early construction are publicly recognized leaders of Tanmen’s militia today.

- February 1989 – The first group tasked with the construction was composed of five fishing vessels and 120 fishermen. They worked for six months on Fiery Cross, Cuarteron, Johnson South, Hughes, and Gaven reefs. This included vessels Qionghai 00206, 00265 (with Wang Shumao as captain), 00805, 0056, and 00441.

- February 1990 – Qionghai 00206 and Qionghai 00265 (with Wang Shumao as captain), with 48 fishermen, spent six months performing construction work at Subi Reef. Qionghai 0480 and its captain/militia member “Old Qiu” (老邱) is also reported to have worked at Subi Reef for three months.

- February 1992 – Qionghai 00226 (with Wang Shubiao as captain), Qionghai 00267 (with Wang Shumao as captain) and Qionghai 00269, with 72 fishermen, spent three months engaged in construction at Fiery Cross, Cuarteron, Johnson South, Hughes, and Gaven reefs.

- February 1995 – Qionghai 00265 (with Wang Shumao as captain), Qionghai 00226 (with Wang Shubiao as captain), Qionghai 00437, and Qionghai 00208, with 96 fishermen, spent six months doing construction work at Mischief Reef.

Deputy Commander Wang Shumao went on all the construction trips reported here and current Platoon Leader Wang Shubiao is reported to have gone on two of them. Despite brutal working conditions and likely using only manual labor, they were able to help construct bunker-style stilted structures and two helicopter pads, and even cut breaks in the reefs for vessels. The sweat shed by the Tanmen Maritime Militia in building these first-generation Chinese structures helped anchor a military presence on disputed features for decades, literally laying a foundation for the PRC’s recent construction of artificial islands on those very same sites.

Participation in the 1995 Mischief Reef Incident

The final construction trip reported above coincides with the Chinese takeover of Mischief Reef in January 1995, when the PRC stationed naval vessels at the reef and erected permanent structures. Chinese open sources confirm that it was the Tanmen Maritime Militia that assisted in transferring the construction materials from PLAN transport ships onto the construction site of the three-stilted structures. Their stated purpose as a “shelter” for Chinese fishermen did little to allay Philippine concerns over Chinese expansion in the Spratlys. As negotiations between Beijing and Manila failed to gain traction, Philippine naval forces set forth to destroy Chinese sovereignty markers on several features. On 25 March 1995, the Philippine navy arrested a group of Chinese fishermen operating south of Mischief Reef for poaching endangered species and planting territorial markers. The four boats detained were Tanmen Maritime Militia vessels led by platoon leader Wang Qiongfa, who helped keep the 62 jailed fishermen from accepting Philippine demands that they sign statements recognizing Manila’s sovereignty over the features. The benefits of a strong Party and militia presence became clear as Wang Qiongfa and his fellow militia unit leaders maintained their staunch verbal defense of China’s South China Sea sovereignty claims, even in a Philippine jail cell. The presence of another group of Tanmen maritime militia members near the site of the standoff indicates that additional units were dispatched to further assist Beijing’s effort to consolidate control over Mischief Reef.

Managing the Militia

While the Tanmen Militia of yesterday and today has contributed greatly to the furtherance of Chinese national objectives, to ensure its dedication to future achievements in the South China Sea’s increasingly roiled waters, further work is needed to control and incentivize its efforts. As they engage in maritime militia construction to meet provincial and national objectives, local officials must balance competing objectives. Three major areas of official effort in this regard are mitigating poaching, providing financial incentives, and monitoring and coordinating fleets.

Poaching, for instance, can reap greater returns in a high-risk environment, especially as traditional fishing yields decline and subsidies fail to compensate. Tanmen officials appear to be making efforts to increase the fishermen’s respect for the rule of law and safety. Because China would like to assert the validity of its domestic law over the sea areas it claims, it is important for the fishermen that regularly populate those waters to recognize China’s domestic law. All along China’s coast, local governments are therefore taking multiple approaches to reconcile these competing incentives. First, they are increasing investment in fishing fleets’ electronic communications equipment, using systems such as the Beidou satellite navigation system and its unique features—such as positioning, messaging, and distress reporting functions—to increase monitoring of them. Second, they are improving the fishing population’s education and training. Tanmen Township officials released notices and held conferences on safe fisheries production for the fishing vessel captains. Third, they are imposing punishments, such as fines or revoking of fishing licenses.

One example that embodies the competing priorities local officials must confront is a large land reclamation project nearby that has alarmed hundreds of Tanmen fishermen. The Provincial Ocean and Fisheries Bureau approved the project in 2010. The project is meant to boost tourism by building a five-star resort hotel, vacation condominiums, parks, and facilities for yachts. The fishermen are worried the increased tourism and related activities will harm their harbor’s environment and their livelihoods. Officials including the head of Qionghai City’s Ocean and Fisheries Department have dismissed the fishermen’s concerns, reaffirming that they do not own the land and therefore have no right to compensation. The company in charge of the reclamation work distributed “compensation” to each village committee in the form of 120,000 RMB (18,534.78 USD), essentially a bribe to preempt opposition from grassroots officials. Other construction work, such as the aforementioned recently-built bridge across Tanmen Harbor, also received some opposition from the local fishermen. While these projects align well with the national mandate to develop Hainan province into an international tourism destination, the rapid changes surrounding such a long-established fishing harbor may foster tensions with the local fishermen, in addition to mounting pressures they face from reduced catches and friction with foreign vessels in the South China Sea.

Such local conditions directly influence the vitality of maritime militia organization. Government support, such as vessel construction and fuel subsidies, help raise the scale of the fishing community’s production, thereby increasing their ability to make profits on each fishing trip. It also helps alleviate any misgivings locals may have over development projects that will likely change the structure of the local economy, especially for a township as small as Tanmen. It also has the dual benefit of both improving their livelihoods and increasing their ability to support China’s maritime claims further out in the South China Sea. The strong political and economic support to this community will be essential if it is expected to continue the struggle for maritime rights and interests in places as far as the Spratlys. It will also help reduce the amount of illicit activities tempting the fishermen, thereby reducing moral erosion in what is supposed to be China’s leading model maritime militia unit.

In 2014 Tanmen implemented a “Fishing Vessel Upgrade and Modification Program,” whereby over 50 wooden-hulled fishing vessels were reconfigured into 300-to-500-ton steel-hulled vessels. Additionally, the Hainan Provincial Government and the Qionghai County Government subsidized construction of twenty-nine 500-ton displacement steel-hulled fishing vessels, most of which have been delivered. The subsidies amounted to more than one-third the cost of the vessels’ construction. They reportedly possess modern equipment and communications gear and provide greater sea keeping and operational ranges. Twelve of these 500-ton vessels are confirmed to have entered service in the Tanmen Maritime Militia, which coincides with the organizational structure outlined above. Tanmen Township is also currently building a new maritime militia detachment; its size and mission focus remain uncertain.

Poaching and its Mitigation

As might be expected among irregular frontiersmen, illicit enrichment through irresponsible fishing in troubled waters remains a perennial problem. Tanmen village’s fishermen are notorious for their illegal fishing activities, despite local officials’ admonitions and neighboring countries’ opposition. While poaching is not exclusive to Tanmen, its fishermen have been caught repeatedly harvesting endangered species of turtles and giant clams. The ever-present demand for products derived from this ‘aquatic ivory’ fuels the high prices Tanmen fishermen can charge. For example, giant clam processing and handicrafts represent an important industry in Tanmen. The Tanmen Township 2014-2030 Marine Economy Industrial Park Plan states that giant clam processing currently constitutes 70% of all the enterprises in operation. Apparently enjoying a plum position in keeping with her family’s disproportionate contribution to the local economy, government policies, and community norms that literally make patriotism pay, Chen Zebo’s wife staffs Tanmen’s clam handicraft shop while he is out to sea. Tourism, in turn, furthers demand for these products. One month after the Scarborough Shoal incident, Tanmen fishermen were busy bringing in large hauls of giant clams, this time under the protection of Chinese MLE escorts.

Returning to the waters near Palawan Island, two Tanmen fishing vessels were caught poaching endangered turtles by the Philippines near Half Moon Shoal on 6 May 2014. One of the vessels, Qionghai 03168, escaped, while Qionghai 09063 was detained. After boarding Qionghai 09063, Philippine authorities immediately shut off the boat’s Beidou Satellite Navigation Transmitter, as indicated by the Tanmen Fisheries and Fishing Harbor Management Station Chief Wang Qizhen. After losing contact with the fishing boat’s Beidou terminal and receiving reports from the fleeing Qionghai 03168, Chinese Fisheries Law Enforcement and Coast Guard forces began searching the area for the lost boat. They sent orders via the Beidou system to fishing vessels Qionghai 03168 and Qionghai 05067 to return to the area of last contact to conduct a search. China Coast Guard vessel 3102 was also pulled away from its task of blockading Second Thomas Shoal to support the search.

The poaching is detrimental to the overall narrative Beijing promotes regarding the South China Sea. This narrative involves China’s effective “administrative control” (管控) over disputed waters. Domestic Chinese regulations and the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora, to which China is a party, both declare the harvest of endangered species such as Tridacnidae (giant clams) to be illegal. Yet Tanmen fishermen blatantly ignore these prohibitions, damaging China’s image both in terms of environmental conservation and effective control over the activities that take place in its claimed waters. The latter is likely a far greater concern for Beijing, considering the scale of reef destruction caused by China’s construction of artificial “islands.” Asia analyst Victor Robert Lee has documented much of the environmental destruction wrought by the giant clam industry, while BBC reporter Rupert Wingfield-Hayes has personally witnessed Tanmen fishermen in the act of poaching. Additionally, continuous arrests of Tanmen’s fishing vessels by Philippine authorities for poaching not only increases China’s diplomatic challenges, but also strengthens the Philippine narrative that it is taking action to protect the marine resources within its maritime claims. The reality at sea may be more complicated, since one Tanmen fishing captain recalled in 2012 that boarding and inspection by Philippine troops is common and he always brings enough cigarettes and alcohol to “pass” the imposed inspection.

There appears to be some effort by China’s local government authorities to reduce illicit harvesting. Recently, meetings were held with many of the fishing boat captains to instruct them not to fish illegally, poach endangered clams or turtles, enter sensitive waters, shut off their Beidou locating transmitters, or take private trips for rights protection. Tanmen officials may be taking heat for lax management of fishermen, especially since Xi placed his seal of approval on the Tanmen fishermen. Local officials may also worry about enthusiastic citizens, incited by official patriotic rhetoric, getting excessively involved in the state’s business of protecting China’s maritime claims.

These bureaucrats may be making parallel efforts in support of specific objectives. First, they seek to gain control over the wayward fishing population, to prevent tensions from flaring because of rising nationalism and illegal activities, to increase safe working conditions, and to demonstrate effective control in disputed sea areas. Second, Chinese leaders seek to maintain a civilian presence in disputed waters to reinforce China’s claims and to create demand for administrative services in the form of MLE protection. Economic realities and the threat of foreign interception can place these efforts in contradiction. Third, development of a more politically motivated, trained, and obedient maritime militia to conduct the state’s business in the South China Sea could be China’s answer to regular MLE presence in its disputed waters.

Financial Incentives

Incentives in the form of fuel subsidies, a special Spratly fishing subsidy, and money to build larger steel-hulled vessels have been implemented to induce Chinese fishermen to build better vessels and to spend the extra time and fuel to travel to more distant waters. With this support, Tanmen fishermen have reportedly ordered 29 new 500-ton fishing vessels from a shipyard in Ningbo, Zhejiang Province; most are already delivered. In 2011, Tanmen fishermen reported receiving a one-time subvention of 35,000 RMB (5,404.48 USD) and 82 RMB (12.66 USD) per KW of engine power in the fishing vessel for each trip taken to Scarborough Shoal or the Spratlys. For example, if known Tanmen maritime militiamen Ke Weixiu takes his new 500-ton fishing vessel with its 700 KW of power to Scarborough Shoal, he will receive 76,000 RMB (11,734.55 USD) for the first trip and 41,000 RMB (6,330.03 USD) for each consecutive trip taken. While this may not be sufficient to incentivize every fisherman to enter contested waters, maritime militia receiving these subsidies can in many cases legally apply for compensation for material losses and personal harm while executing mission orders. One Tanmen fishing captain interviewed by the Australian Broadcasting Corporation stated “We won’t go there [to the Spratlys] if the Government doesn’t pay us subsidies of about $20,000 each time, and we only get it if we commit to going four times a year. We don’t make money from the fishing.” Armed with more capable vessels and subsidies in hand, Tanmen maritime militia likely make more frequent trips to disputed waters than regular fishermen. This elite presence is precisely what China seeks to promote in sensitive waters.

Fleet Monitoring and Coordination

China’s indigenous Beidou/Compass satellite navigation system, a regional rival of the American global satellite positioning, navigation, and timing (PNT) system and now installed on thousands of Chinese fishing vessels, appears frequently in state news. This system is an important tool for government departments monitoring China’s fishing fleets. Chinese media report that China’s fishing vessels receive government warnings when they cross into foreign waters that Beijing does not claim. Interestingly, for this to occur the Beidou system must possess a defined set of coordinates for China’s U-shaped maritime boundary claim that enables warnings to be issued when a fishing vessel ventures beyond “China’s waters.” Unfortunately, these coordinates for China’s “nine-dashed line” remain unknown to outsiders.

The Beidou system’s marine vessel monitoring system integrates positioning with communication, featuring a unique 120-character short-messaging service and an emergency distress button that instantly alerts fisheries authorities. Akin perhaps to a silent alarm used to catch bank robbers, this allows fisheries authorities to determine the vessel’s position and dispatch rescue forces to the location. The widespread installation of these satellite PNT systems, in combination with other communications gear given to the maritime militia, allows Chinese authorities to essentially form a “maritime border early warning” (预警国家海上边界) network. In the case of the People’s Armed Police Border Defense Station in Tanmen Township, Fu Shibao mans what has become colloquially known as the “South China Sea 110” (China’s equivalent to America’s 9-1-1 emergency service). His shore station uses the Beidou system, radios, and cellular coverage to maintain communications with approximately 135 of Tanmen’s vessels operating in the Paracels, Spratlys, and Macclesfield Bank. Each day he spends hours contacting these vessels at sea to check their status, provide weather updates, and disseminate important information about neighboring countries that would be of concern to the fishermen. Despite his assignment to a grassroots-level station, Fu and others manning the Tanmen Border Defense Station are able to provide disproportionate, continuous contributions to China’s overall maritime domain awareness in the South China Sea. Such a role was seen during the Scarborough Shoal standoff, wherein timely militia-to-police grassroots-level reporting provided the awareness for more professional forces to respond.

Given overall trends, in which a rising tide of economic growth and government investment may be channeled to raise all boats, local officials are able to foster maritime militia construction while furthering their other goals. Nevertheless, significant mission-incentive misalignments persist, requiring further efforts at their reconciliation.

Conclusion: A Frontline Force Today… and Tomorrow

Xi Jinping’s designation of the Tanmen Maritime Militia as the model for others to emulate is no coincidence. Even among the leading maritime militias of Hainan Province, no other unit has made such significant contributions over time to Chinese feature construction and “rights” promotion in the increasingly-contested South China Sea. This long track record and official sanction has left a lengthy paper and electronic trail, a gold mine for open source research. This article has therefore examined in particular depth the Tanmen militia’s structure, missions, and management in order to better understand this leading organization, which remains a trusted tool of Beijing’s maritime policy, and to appreciate the lessons that other irregular Chinese sea forces may be drawing from its elevation.

The Tanmen Maritime Militia’s recent popular history is one of a small fishing village on the edge of a large civilization, working to address a tide of foreign encounters and national-level political movements. While most Tanmen fishermen did not previously consider their work to have national ramifications, recent Central Party policies and initiatives are changing that. President Xi and numerous other officials’ visits to Tanmen and elsewhere in the past few years have officially politicized the operations of China’s fishermen in the South China Sea. Local Party officials are re-invigorating an old communist tactic of ensuring Party control over China’s fishing fleets, with Tanmen’s maritime militia designated the exemplar for all others to follow. Tanmen Maritime Militia Company, with growing government support and guidance, will be expected to lead the fishing fleets to China’s claimed waters and provide support in the everyday struggle against foreign “aggression” in the South China Sea. Already, Tanmen Militia forces have helped to consolidate Chinese control over Mischief Reef and Scarborough Shoal, and to defend the HYSY-981 oil rig. Having long supported feature augmentation and facilities construction in the Spratlys, they might again be called to do so—particularly in situations calling for low-profile activity.

While this two-part article focuses primarily on activity after the modern Tanmen Militia’s formal establishment in 1985, Tanmen fishermen have a much longer relationship with the South China Sea. They are considered by Beijing to have stood the test of time, making their very existence and presence of value to its far-reaching maritime claims. Numerous instances of daring rescues and unshakeable nerve in the face of foreign attempts to contest maritime rights notwithstanding, the Tanmen Maritime Militia also represent an important model for emulation by other localities’ officials building up their own maritime militia.

Looking forward, recent reports suggest increased Chinese survey activity on Scarborough Shoal, with sources pointing to possible land reclamation efforts there later this year—perhaps as partial retribution for the forthcoming Philippine Arbitration ruling, likely to be issued in June 2016. Just as the Chinese government insisted so vehemently on having civilian designs in the feature augmentation and development it conducted in the Spratlys, any reclamation at Scarborough Shoal will likely be under the same pretext. Growing regional tensions over this possibility may prompt China to instead use the Tanmen Maritime Militia once again to construct a first generation of civilian structures, which might serve as the foundation for future artificial island bases. Underpinning this next step in Chinese geo(political)-reengineering would be the fishermen and maritime militia of Tanmen Township, who have paid the human price to maintain a Chinese presence at Scarborough Shoal. As U.S. Freedom of Navigation operations and other foreign activities occur in proximity to Beijing’s sweeping claims, Tanmen militiamen are likely to continue their frontline role as irregular defenders of the nation’s “maritime rights and interests.”

The next article in our series will delve into the establishment and development of the maritime militia of Sansha City, China’s newest city located on Woody Island in the Paracels. Often living on the Chinese occupied features of the South China Sea, Sansha City’s maritime militia are the true front-line defenders of China’s maritime claims. Surrounding these largely-transplanted island people is a growing torrent of reclamation and infrastructure investment in an increasingly (para)militarized South China Sea.

Dr. Andrew S. Erickson is a Professor of Strategy in, and a core founding member of, the U.S. Naval War College’s China Maritime Studies Institute. He serves on the Naval War College Review’s Editorial Board. He is an Associate in Research at Harvard University’s John King Fairbank Center for Chinese Studies and an expert contributor to the Wall Street Journal’s China Real Time Report. In 2013, while deployed in the Pacific as a Regional Security Education Program scholar aboard USS Nimitz, he delivered twenty-five hours of presentations. Erickson is the author of Chinese Anti-Ship Ballistic Missile Development (Jamestown Foundation, 2013). He received his Ph.D. from Princeton University. Erickson blogs at www.andrewerickson.com and www.chinasignpost.com. The views expressed here are Erickson’s alone and do not represent the policies or estimates of the U.S. Navy or any other organization of the U.S. government.

Conor Kennedy is a research assistant in the China Maritime Studies Institute at the US Naval War College in Newport, Rhode Island. He received his MA at the Johns Hopkins University – Nanjing University Center for Chinese and American Studies.

Featured Image: “Escort Fleet” protects the HYSY-981 Oil Rig. Source: Phoenix News