By Dick Mosier

With the fielding of increasingly capable anti-ship missiles, the centerpiece of the next conflict with a near-peer maritime power will be warfare to deny the adversary the intelligence, surveillance, reconnaissance and target acquisition information required for successful anti-ship missile attack on surface combatants and capital ships. Land, air, surface ship, and submarine launched anti-ship missiles are and will increasingly be the dominant threat to surface navy operations. Ballistic anti-ship missile systems such as the Chinese Dong Feng 21 (DF21D) and Dong Feng 26 (DF26); hypersonic anti-ship missiles such as the Russian 3M22 Zircon (NATO SS-N-33); and, anti-ship cruise missiles leveraging artificial intelligence for threat avoidance and target acquisition dramatically increase the threat and severely challenge the anti-ship missile defense capabilities of the surface navy.

The trend favors the offense. The longstanding and current investments in fleet kinetic and electronic defense against incoming launch platform or inbound anti-ship missiles will remain necessary but increasingly insufficient. A sea-skimming, Mach 6, ZIRCON anti-ship missile, breaking the radar horizon at 15nm from a surface target, would impact the ship in approximately 15 seconds. With these short reaction times the likelihood of a navy surface ship detecting and destroying the incoming missile is low.

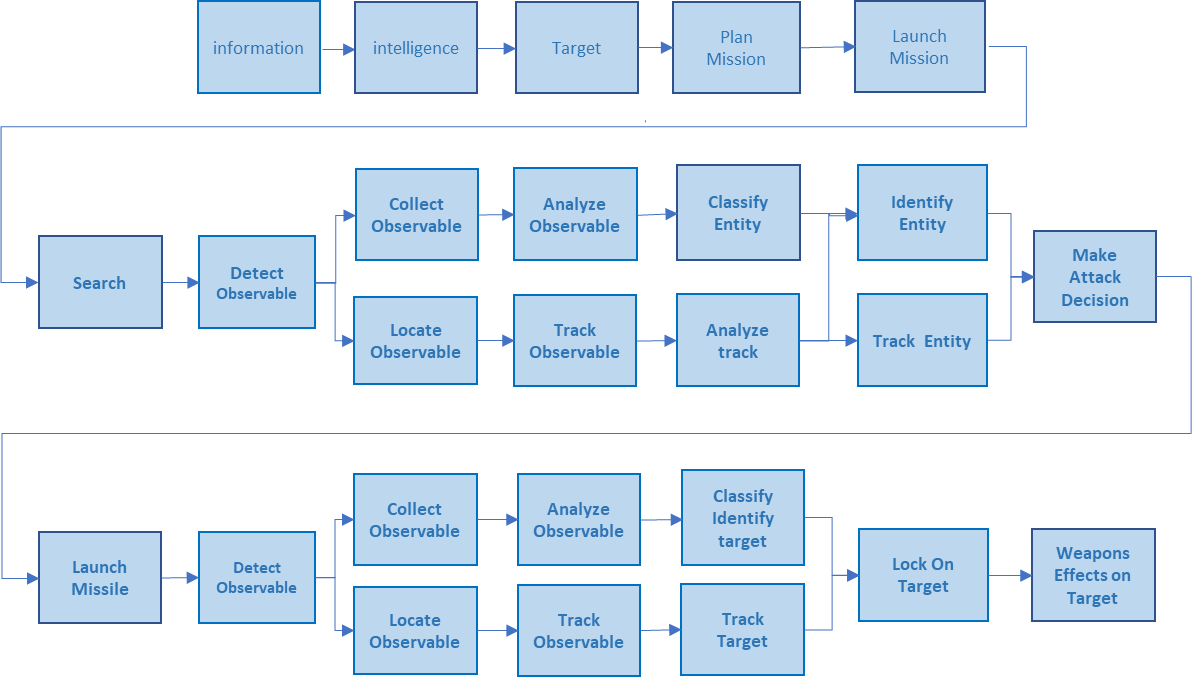

One way to offset this dramatically increased threat is to counter the adversary’s intelligence, surveillance, reconnaissance (ISR) and target acquisition (TA) capabilities. Even the most sophisticated anti-ship missile systems are dependent on a chain of events starting with intelligence to support the targeting decision process, followed by reconnaissance and surveillance to find the target, and ending with weapons effects on the target. It includes the communications and data links for the transfer of information along the kill chain and the command and control decisionmakers. The attack will be unsuccessful if any of the links in this anti-ship missile kill chain are broken.

The concept of a kill chain is well established in the U.S. military as evident in terms such as Sensor-to-Shooter; Observe, Orient, Decide, Act (OODA); and Find, Fix, Track, Target, Engage, and Assess (F2T2EA). Though similar in concept, the kill chain for anti-ship missile attack against moving maritime targets requires a detailed decomposition to identify the links in the chain of events that must be completed for attack success. The following is a representation of a notional anti-ship missile kill chain.

The links in the kill chain that reference “observables” all depend on own force/own ship offering visual, infrared, acoustic, RF (radar, communications, data links) observables that can be exploited by the adversary to complete the kill chain. In addition to technical observables, the operations of the force/own ship offer observables such as course, speed, and formation from which to deduce that the entities are military and that entities being screened by a formation might be the highest value. Many of the observables that can be exploited by the enemy to acquire this information can be controlled or manipulated to degrade links in the enemy’s anti-ship kill chain.

In response to the rapidly evolving threat, the Navy needs a strategy that officially recognizes the requirement and places high priority on breaking the anti-ship missile kill chain. There are several elements to the execution of this strategy. First, it requires very detailed intelligence on the end-to-end kill chain for each type of anti-ship missile, identifying, locating, and assessing the technical characteristics and performance of each link in the chain. Second, it requires operational intelligence on how a potential adversary actually uses or trains to operate the kill chain for each type of missile. Third, it requires analysis of the observables offered by U.S. Navy combatants that could inform an adversary’s kill chain. Having knowledge of all three elements, the analysis can be performed to identify both material and non-material alternatives; and assess their effectiveness, technical and operational feasibility, probability of success, and costs.

Breaking the anti-ship missile kill chain requires a response that integrates a variety of national, theater, and Navy information-related activities executed ashore and afloat. Composite Warfare Commanders and their supporting Information Operations Warfare Commanders will be required to have detailed knowledge of adversary ISR and TA systems and their capabilities. They will require situational awareness sufficient to determine whether the force is within enemy detection range, and assess whether the adversary has located and identified the force. This assessment drives the decision of if and when to transition from denying observables to active electronic and kinetic defense when it is tactically advantageous.

It will also require creation of a new warfighter career path focused on countering enemy ISR and TA and breaking the anti-ship missile kill chain. This career path would be technically challenging, requiring personnel educated in the physics of the various types of sensing, such as satellite reconnaissance, Over-The-Horizon Radar (OTH-R), Inverse Synthetic Aperture Radar (ISAR), time difference of arrival (TDOA), frequency difference of arrival (FDOA), imaging and non-imaging IR, and acoustic systems. The knowledge of physics at work in the acoustic, atmospheric, and ionospheric environments and in the various types of sensing systems has to be followed by knowledge of how various techniques are employed by adversaries along individual steps of the kill chain when hunting surface ships and aircraft. This foundation of knowledge forms the basis for the conceptualization and testing of new concepts, formulation of new requirements, the fielding of new systems, the development of doctrine and tactics, and manning of the fleet with ready warfighters.

In summary, the fielding of ballistic and hypersonic anti-ship missiles by Russia and the China constitutes an alarming increase in the threat to U.S. Navy surface ships. It demands a strong, focused, offsetting response aimed at defeating these new weapons by breaking their respective anti-ship missile kill chains. This strategy will be successful only if it is treated as a major new direction for the U.S. Navy, with sustained high-level support, strong organization, and innovative leadership.

Dick Mosier is a recently retired defense contractor systems engineer; Naval Flight Officer; OPNAV N2 civilian analyst; SES 4 responsible for oversight of tactical intelligence systems and leadership of major defense analyses on UAVs, Signals Intelligence, and C4ISR. His interest is in improving the effectiveness of U.S. Navy tactical operations, with a particular focus on organizational seams, a particularly lucrative venue for the identification of long-standing issues and dramatic improvement. The article represents the author’s views and is not necessarily the position of the Department of Defense or the United States Navy.

Featured Image: Sputnik/ Ildus Gilyazutdinov