By Aidan Clarke

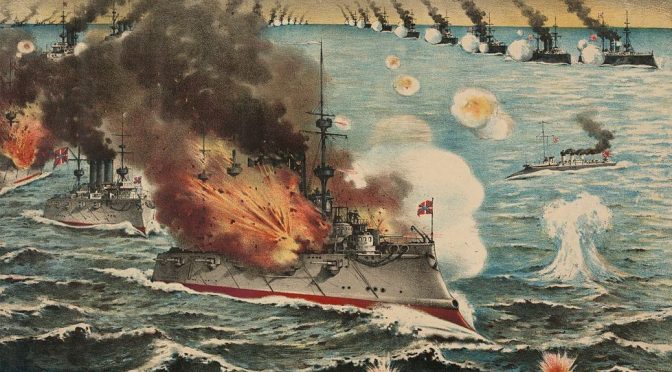

The Russo-Japanese War saw the Imperial Russian Navy soundly beaten by the Imperial Japanese Navy. While much of the analysis on the Russo-Japanese War focuses on the Battle of Tsushima and the success of the Japanese Admiral Tōgō Heihachirō, one can also look to understand the deficiencies present in the Imperial Russian Navy that contributed to this defeat. The causes for this shocking defeat can be compared with the challenges of the Russian Empire as a whole. Russian naval culture, like that of its civilian society, had been built on an outdated system of social class, with nobles (particularly nobles with partial German ancestry) rising as officers, while talented sailors languished in the conscripted ranks. Just as the Tsar’s attempts at reforming Russian society failed to fully solve the deep-seated cultural problems of the Empire, and prevent the 1905 Revolution, Russian attempts at naval reform through the 1885 naval qualifications statute would also fail creating a new class of risk-averse and bureaucratic officers. The initial naval battle outside Port Arthur, and the ultimate defeat of the Port Arthur squadron in the Battle of the Yellow Sea, reflect these failings.

A Fish Rots from the Head

Of all the weaknesses which the Imperial Russian Navy suffered from during the Russo-Japanese War, none were so glaring as the failings of the officer corps. These officers were generally more concerned with their own advancement rather than success in battle. Tellingly, they suffered from over-bureaucratization and a failure to encourage initiative among their ranks.

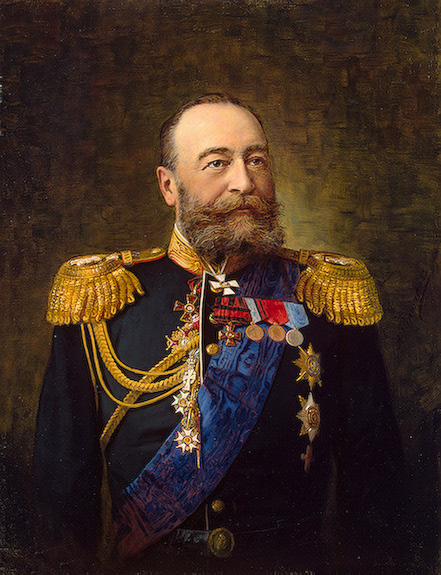

Before the war, the Russian Navy was more superficial than substantive, suffering from general disorganization, as well as shortcomings of its personnel. While Tsar Nicholas “was attracted to military traditions and pageantry” he was also uninformed, and willing to tolerate “the often unproductive interference of uniformed Grand Dukes in the running of the army and navy.”1 The role of the nobility in the navy was a pernicious problem for Imperial Russia. In 1881, the highest position in the Imperial Navy, the General Admiral, was given to Grand Duke Alexei Alexandrovich, who was Tsar Nicholas’ uncle. Almost certainly his position was not given on his merit, as the Director of the Navy Ministry, Vice Admiral I.A. Shestakov, felt the Grand Duke was “not an efficient administrator, being more interested in external appearances and the opposite sex than tackling professional issues.”2 The professional problems of the Imperial Russian Navy also extended to the realm of strategic planning and discourse. Prior to the war, the navy had no general staff, and “until the outbreak of the war in 1904, the Navy Ministry had not issued a coherent official tactical doctrine.”3 There was almost no centralized planning at all in the navy, with operational strategy left to “makeshift fleet staffs in different geographical theaters” and subject to the “personal directions and whims” of regional commanders.4

In order to reduce nepotism in the advancement of naval officers and promote professionalism in the navy, the Russian state implemented the naval qualifications statute of 1885, under which “promotions were regulated by a rigid system hinging on specific terms spent at sea, available vacancies, and recommendations by superiors.”5 Ostensibly, this common-sense reform ought to have improved professionalism and efficiency within the fleet. Unfortunately, in most cases it had the opposite effect. The new promotion system “stifled talent and initiative”6 while encouraging officers to maintain a “bureaucratic temperament.” This meant that rather than adapting to the circumstances and seizing on enemy weaknesses, Russian officers “placed great stress on avoiding situations where they might attract criticism from above.”7 They focused on “external appearances and the superficial completion of service requirements.”8 In other words, captains and admirals spent more time inspecting brass pipes and white uniforms than they did testing the readiness of their men for war. This system meant that “the typical Russian officer seemed more at peace within himself when it was the enemy who had the initiative.”9 According to J.N. Westwood, “Russian naval officers were the product of a bureaucratic society in which avoidance of blame was more important than technical competence or imaginative enterprise.”10 This has been a common problem in naval history, perhaps most visible in the stagnation of the Royal Navy, laid bare in the Battle of Jutland.11

From the onset of the war, this failing reared its ugly head. The Commander of the Russian Pacific Squadron, Vice-Admiral Oscar Victorovich Stark, had recognized the dangers posed by Japan in light of the deteriorating diplomatic situation. He had repeatedly requested Admiral Yevgeni Ivanovich Alekseyev, Commander in Chief of Imperial Forces in Port Arthur and Manchuria, as well as Viceroy of the Imperial Russian Far East, “to permit him to prepare the fleet for war.”12 However, Alekseyev dismissed Stark’s fears on the grounds that they were “premature and escalatory.”13 Admiral Alekseyev did not see much of a threat from the Japanese, and a report from Vice-Admiral Wilhelm Withöft (a Russian-German noble) argued that the Russian “plan of operations should be based on the assumption that it is impossible for our fleet to be beaten.”14 Regardless, Vice-Admiral Stark did attempt to work around these restrictions, ordering his crews to put out torpedo nets and prepare for a Japanese surprise attack. However, he could not appear to undercut the noble Withöft or Alekseyev (who was a son of the Tsar), and in the end, “so low-key was the instruction in relation to the Supreme Commander’s known views that…nothing was done.”15 Captains and crews did not wish to contradict Admiral Alekseyev, regardless of the orders from the local commander, and few took any precautions.

There is a common misperception of soldiers and sailors as mindless automatons, following orders like pieces on a chess board. In this image, there is little wrong with the decision of the officers of the Pacific Squadron to yield to the will of Alekseyev and not that of Vice Admiral Stark. However, by the time the Russo-Japanese War began, this model was already outdated, and had largely been replaced with the relatively new concept of auftragstaktik (commonly translated as mission command in English).16 Mission command requires junior officers to “use their own initiative” and adapt to their own circumstances in order to achieve a mission defined by “a superior commander’s concept of operations.”17 Mission command is ultimately a superior model because it recognizes that those on the frontlines often have the best perception of their own situation, and that communication in war is susceptible to interruption, confusion, and misunderstanding (the fog of war). Allowing local commanders to maneuver as best suits them will allow them to minimize their casualties and complete their objectives more rapidly, while avoiding wasted opportunities or fatal miscommunications. In this context, as the local commander, Vice-Admiral Stark had a much clearer view of the threat posed by Japan, while Alekseyev, concerned with Russian objectives across all of Asia, did not. Admiral Alekseyev’s failure to defer to the local awareness of Vice Admiral Stark reflects Russia’s failure to adapt to modern military thought.

Admiral Alekseyev deserves special attention in considering the failures of the Russian officer corps. Directly beneath him in the chain of command were Vice-Admiral Makarov (after his replacement of Vice-Admiral Stark) and General Kuropatkin. It should be recognized that these two figures were viewed as “the two best officers for their respective posts.”18 Makarov in particular was “Russia’s most competent admiral” and “was certainly Tōgō’s equal.”19 Despite this, Russia’s cultural deference to the nobility left Makarov and Kuropatkin “under Alekseyev, whose ego far outstripped his energy and competence.”20 Stark, Makarov, and ultimately, Withöft all found themselves hamstrung by their superiors, while the Japanese left Admiral Tōgō Heihachirō free to operate as he saw fit. This was a critical difference, and it played a major role in Russia’s ultimate defeat.

That is not to say that Vice-Admiral Stark or any of his replacements should be absolved of blame. Frederic William Unger, an American war correspondent who followed and wrote extensively about the war, noted that when the first Japanese attack on Port Arthur began, “Many of the Russian naval officers were ashore, celebrating with appropriate festivities the birthday of Admiral Stark.”21 While others including J.N. Westwood dispute this claim, Richard Connaughton argues that the party was “entirely in keeping with his reputation as a fun-loving partygoer.”22 Perhaps more importantly, the party’s guests included Admiral Alekseyev himself, as well as several other critical officers. Thus, on the night of February 8th, when Admiral Tōgō launched his initial torpedo attack, the Russian pacific squadron was unprepared and leaderless. Within ten minutes a Russian cruiser, the Pallada, a battleship, the Retvizan, and worst of all, the pride of the Russian Navy and most powerful ship in the Pacific Squadron, the Tsarevitch, had all been hit by torpedoes and were at least temporarily disabled. The Retvizan in particular suffered badly. Having hit Retvizan in the bow, a Japanese torpedo was able to open “a hole through which a car could be driven.”23

The loss of these ships, although temporary, would prove critical. Over the next several months, the Japanese enjoyed total control of the seas, while the Russian Navy could only attempt to rebuild its capabilities. This allowed the Japanese a free hand to land vast numbers of troops in Manchuria, forcing the hand of the Russian Navy, and creating the circumstances for Japan’s ultimate victory.

Battle of the Yellow Sea: The Death of the Pacific Squadron

As Japanese ground forces fought their way closer to Port Arthur, they began raining artillery down on the Pacific Squadron, which for the last six months had failed to even attempt to contest control of seas.24 Petrified as they were of failure, the death of Admiral Makarov in the entrance to the harbor as his ship hit a mine, paralyzed all ensuing Russian officers. In August 1904, as the land battle continued to rage, Viceroy Alekseyev demanded that the most recently appointed commander of the Pacific Squadron, Rear-Admiral Wilhelm Withöft, take the remainder of the Russian Pacific Squadron to Vladivostok. Withöft stalled as long as he could, but before long he “received orders of a more peremptory tone from both the Viceroy and the Tsar.”25 Despite the urging of his superior, Withöft held several councils of war, and together he and his captains agreed that their position dictated they stay in port. Alekseyev ignored Withöft and repeated that this decision was not only in contradiction to his orders, but was also against the wishes of the Tsar.26 Finally, after yet more protests from Withöft, Alekseyev informed the Vice-Admiral that “if the Port Arthur squadron failed to put to sea despite his and the Tsar’s wishes, and was destroyed in Port Arthur, it would be a shameful dishonor.” Furthermore, Alekseyev reminded Withöft of the example of “the cruiser Varyag” which had “put to sea fearlessly to fight a superior force.”27 Of course, Alekseyev did not mention the fate of the Varyag, though Withöft doubtless knew it had been demolished by heavy Japanese fire and had been scuttled at great cost to its crew.

The refusal of the squadron to put to sea appears as cowardice, but in truth, there was good logic to Withöft’s decision to stay in port. Firstly, Withöft was still under the impression that the Russian Baltic Squadron would arrive by October. So reinforced, the Russian Pacific Squadron would be able to concentrate their force, allowing them to confront Tōgō with “overwhelming Russian battleship superiority,” forcing the Japanese admiral to either abandon the field or face near certain defeat. Port Arthur only needed to hold on for three months, and the war could yet be won. Furthermore, the ships of the Port Arthur squadron were contributing supporting fire to the defenders of the Port, and their mere presence prevented the possibility of a Japanese amphibious attack. In short, “an inert Russian squadron in Port Arthur was of far greater strategic value than a bold squadron at the bottom of the sea.”28

Withöft’s logic had one inherent flaw: the Baltic squadron would not arrive by October, in fact it would not even arrive for another nine months. Alekseyev was “probably aware”29 that this was the case, but neglected to inform the local commander, instead offering only strict and inflexible orders. Under these circumstances, bureaucratic Russian officers responded the only way they could, with fatalistic obedience. Accusations of cowardice on the part of Withöft and his captains are inaccurate: “they were more frightened of failure than death.”30

On August 10th, 1904, the Pacific Squadron put to sea with six battleships, four cruisers, and eight torpedo boats. The Japanese matched them with four battleships, six or seven cruisers, 17 destroyers, and 29 torpedo boats.31 While this did give the Russian fleet a nominal advantage in first-class battleships, two of the six “were the old, lumbering, Poltava and Sevastopol.”32 There seemed to be no doubt of the outcome in the mind of Admiral Withöft, whose last words before stepping onto his flagship were: “Gentlemen, we shall meet in the next world.”33 As the ships of the Port Arthur squadron began their flight for Vladivostok, they “displayed the unwelcome effects of a fleet cooped up in port.”34 Stricken with mechanical issues, Russian engineers worked frantically to achieve the maximal speed of the squadron, while their ships lagged and the formation was repeatedly forced to stop and wait for others to catch up. Later, the Russian gunnery would suffer from a lack of practice as well. As the Russian ships affected their repairs, the faster Japanese ships were also allowed to catch up, and the battle began in earnest at 12:30 PM.35

For the next five hours, the two fleets would shell each other from long range. For most of the battle, the Russians gave as good as they got, scoring powerful hits on the leading Japanese ships, Mikasa, Shikishima, and Asahi. As Mikasa took a number of hits, she, and the Japanese line, began to slow. Tōgō soon found himself trailing behind the Russian fleet. “He had been out-maneuvered” and Vice-Admiral Withöft “had secured the best position possible.”36 Then, as it so often does, pure chance completely changed the course of the battle.

At 5:45 PM, a pair of Japanese 12-inch shells slammed into the bridge of the Russian flagship Tsarevitch, killing Admiral Withöft and all of his staff, and jamming the wheel of Tsarevitch hard over, forcing the Russian flagship into a dramatic circle.37 It was at this point in the battle that the failings of the Russian officer corps became manifest. Contemporary accounts and modern historians agree that “the effort of the Russian ships to fight their way through the Japanese would probably have been successful…had it not been for the disaster to the battleship Tsarevich.”38 Without Withöft, chaos reigned in the Russian fleet. Withöft’s replacement as commander of the squadron was Prince Pavel Petrovich Ukhtomsky. Ukhtomsky’s immediate problem was that his signals mast and lines were shot away, forcing him to signal from the bridge, where only the ships nearest him could see them. However, this was probably the least of the Prince’s problems. As he signaled “follow me” to his ships, Prince Ukhtomsky turned back toward Port Arthur – a somewhat ironic decision given that he had been one of the officers pushing Vice Admiral Withöft to attempt a breakout to Vladivostok in the first place.

Ukhtomsky was not held in any high regard in the Russian Navy. Many in the fleet believed that “he owed his position to connections rather than ability” and he was derided as “a second rate man.”39 His decision to return to Port Arthur made little sense, as the Russian stronghold “could no longer offer a safe haven” and “there was a strong probability that that a significant part of the squadron could have reached Vladivostok.”40 Just as in the forthcoming 1905 revolution, some of the Russian ships simply refused to follow the orders of the nobility, personified by Prince Ukhtomsky. In particular, the light cruiser Novik made a dash for Vladivostok, but was finally defeated after being sighted by a Japanese freighter.41

While the majority of the Russian ships did return to Port Arthur, the Russian mission was a dramatic failure. Although it had lost only one battleship (Tsarevich was forced to shelter in a German port where she was interned), the Port Arthur squadron was so damaged that it would never put to sea again. Russian ground troops were disgusted by this failure, and according to a Russian correspondent, “there was nothing but abuse and curses for the naval officers, from the highest to the lowest.”42 Prince Ukhtomsky’s decision to turn around and return to Port Arthur was an enormous blunder. In so doing, he trapped himself and the squadron in the port, where they would be shelled and sunk, eliminating any value they could have offered to Admiral Rozhestvensky and the Baltic fleet. While he may have feared the loss of most of his ships, “even one battleship at Vladivostok would have been a serious embarrassment for Tōgō when he faced the oncoming Baltic squadron.”43 Instead, Ukhtomsky’s decision removed the Port Arthur squadron entirely from the playing field. This was an immense strategic victory for Japan, who could now use their artillery to sink the Russian ships, while allowing Tōgō and the Navy to prepare for the upcoming battle with the Baltic Squadron.

Conclusion

The Battle of Tsushima was decided well before the Russian and Japanese Fleets met. Admiral Rozhestvensky’s words on the expedition indicate his feelings on the prospects of the mission: “We are doing now what needs to be done still, defending the honor of the flag. It was at a previous stage that another course ought to have been taken….Sacrifice the fleet if need be, but at the same time deliver a fatal blow to Japanese naval power.”44 These words, so drenched in the presumption of defeat and complete fatalism, rival those of Admiral Villeneuve on the eve of Trafalgar as some of the least inspiring in naval history. Rozhestvensky was right of course, he had little hope of defeating the Japanese. His fleet was comprised of untrained officers and crews on brand-new ships, which were as yet untested. He had to sail across the globe, hardly stopping for shore, and having to deal with embarrassments such as the Dogger Bank incident, when his untested and nervous crews mistook British fishing trawlers for Japanese torpedo boats, and began pouring fire into them. This incident caused a great deal of enmity towards Russia, causing the Royal Navy to shadow Rozhestvensky for much of his journey, and a number of other nations to deny him access to their port facilities for resupply. When the time for battle finally came, the Russians were disorganized and unprepared. Untested in battle, their fire was “indifferent and ineffective.”45 The exhausted and overwhelmed Rozhestvensky was badly wounded and could only watch as the Japanese picked his fleet apart.

However, Russia’s naval failures in the Russo-Japanese War cannot be laid entirely on his account. Had the Tsar been able to consolidate his squadrons before giving battle to the Japanese, the outcome of the war would likely have been vastly different. However, without any fleet-wide strategic or operational planning, the Imperial Navy was left disjointed and dispersed, while the Japanese could concentrate their forces in their home waters. What little planning there was took place on a localized level, and was hampered by feckless, disinterested officers, parochial interests, corruption, and nepotism, wasting Russia’s quantitative advantages.

However, perhaps the decisive factor in the Russo-Japanese War was the bureaucratic and indecisive nature of the officers in the Russian Navy. Rather than encourage initiative and free their captains to adapt to the circumstances at hand, Russian naval culture rewarded paper pushers and officers whose crews spent more time cleaning their guns than firing them. Worse still, a gerontocratic Russian state meant that modern techniques and technologies were ignored in favor of the outdated practices of noble officers, who had little interest or ability in naval warfare. Russian officers were thus hesitant in the moments of crisis, incapable of decisive action. Meanwhile, their crews, filled with conscripts and trained for inspections rather than combat, were entirely outmatched by the remarkably professional and extremely well-motivated Imperial Japanese Navy.

Japanese victory in the Russo-Japanese War was undoubtedly the result of Japanese superiority in a number of critical areas. However, the most telling asymmetry between Japan and Russia in the war was the disparity between their leadership, laid bare in the heat of battle.

Aidan Clarke is an undergraduate student at Furman University, double majoring in History and Politics and International Affairs, with an interest in naval affairs. He has previously researched the U.S.-Soviet naval showdown during the Yom Kippur War, and is currently conducting a research project on the Russo-Japanese War.

References

1. Nicholas Papastratigakis, Russian Imperialism and Naval Power, Military Strategy and the Build-up to the Russo-Japanese War, 2011, (New York: I.B. Tauris & Co. Ltd), 45.

2. Ibid, 46.

3. Ibid, 47; Ibid, 42.

4. Ibid, 48.

5. Ibid, 53.

6. Ibid, 53; J.N. Westwood, Russia Against Japan, 1904-05. 1986, (New York: State University of New York Press), 1.

7. Ibid 29

8. Papastratigakis, Russian Imperialism and Naval Power, Military Strategy and the Build-up to the Russo-Japanese War, 53.

9. Westwood, Russia Against Japan, 1904-05. 29.

10. Ibid, 35.

11. Andrew Gordon, The Rules of the Game, 2012, (Annapolis, MD, US Naval Institute Press).

12. Richard Connaughton, The War of the Rising Sun and the Tumbling Bear, 1991, (New York: Routledge, Chapman, and Hall, Inc.) 30.

13. Ibid

14. Westwood, Russia Against Japan, 1904-05, 37.

15. Connaughton, The War of the Rising Sun and the Tumbling Bear, 30.

16. Connaughton, The War of the Rising Sun and the Tumbling Bear, 117.

17. Ibid; “Concept of operations” should be understood as the overall strategic or operational objective.

18. Ibid, 38.

19. Westwood, Russia Against Japan, 1904-05, 46.

20. Connaughton, The War of the Rising Sun and the Tumbling Bear, 38.

21. Frederic William Unger, The Authentic History of the War between Russia and Japan, 1904, (Philadelphia: World Bible House), 345.

22. Connaughton, The War of the Rising Sun and the Tumbling Bear, 31.

23. Connaughton,The War of the Rising Sun and the Tumbling Bear, 32.

24. Unger, The Authentic History of the War between Russia and Japan, 344.

25. Westwood, Russia Against Japan, 1904-05, 80.

26. Ibid, 81.

27. Ibid, 80.

28. Ibid, 81.

29. Ibid.

30. Ibid.

31. Unger, The Authentic History of the War between Russia and Japan, 391; “Japanese Win Naval Battle in Corean Strait,” Chicago Tribune, August 14, 1904, Pg. 1, Accessed via ProQuest Historical Newspapers; Connaughton, The War of the Rising Sun and the Tumbling Bear, 172.

32. Connaughton, The War of the Rising Sun and the Tumbling Bear, 171.

33. Ibid, 172.

34. Ibid.

35. Connaughton, The War of the Rising Sun and the Tumbling Bear, 172.

36. Westwood, Russia Against Japan, 1904-05, 83.

37. Westwood, Russia Against Japan, 1904-05, 85; Connaughton, The War of the Rising Sun and the Tumbling Bear, 173.

38. “Japanese Win Naval Battle in Corean Strait,” Chicago Tribune, August 14, 1904, Pg 1.

39. Connaughton, The War of the Rising Sun and the Tumbling Bear, 174.

40. Westwood, Russia Against Japan, 1904-05, 86.

41. Westwood, Russia Against Japan, 1904-05, 86; Connaughton, The War of the Rising Sun and the Tumbling Bear, 174.

42. Connaughton, The War of the Rising Sun and the Tumbling Bear, 174.

43. Westwood, Russia Against Japan, 1904-05, 86.

44. Westwood, Russia Against Japan, 1904-05, 138.

45. Connaughton, The War of the Rising Sun and the Tumbling Bear, 266.

Bibliography

Chicago Tribune (Chicago, IL). “Japanese Win Naval Battle in Corean Strait.” August 14, 1904. https://search-proquest-com.libproxy.furman.edu/docview/173171585/7CB7EBC23EDC4AE5PQ/13?accountid=11012.

Connaughton, Richard. The War of the Rising Sun and Tumbling Bear. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Routledge, 1991.

Gordon, Andrew. The Rules of the Game. Annapolis, MD: US Naval Institute Press, 2012.

Koda, Yoji. “The Russo-Japanese War—Primary Causes of Japanese Success.” Naval War College Review 58, no. 2.

Papastratigakis, Nicholas Papastratigakis. Russian Imperialism and Naval Power, Military Strategy and the Build-up to the Russo-Japanese War. New York, NY: I.B. Tauris, 2011.

Stone, David R. A Military History of Russia. Westport, CT: Praeger Security International, 2006.

Unger, Frederic William. The Authentic History of the War between Russia and Japan. Edited by Charles Morris. Philidelphia, PA: World Bible House, 1904.

Westwood, J.N. Russia against Japan, 1904-05. New York, NY: State University of New York Press, 1986.

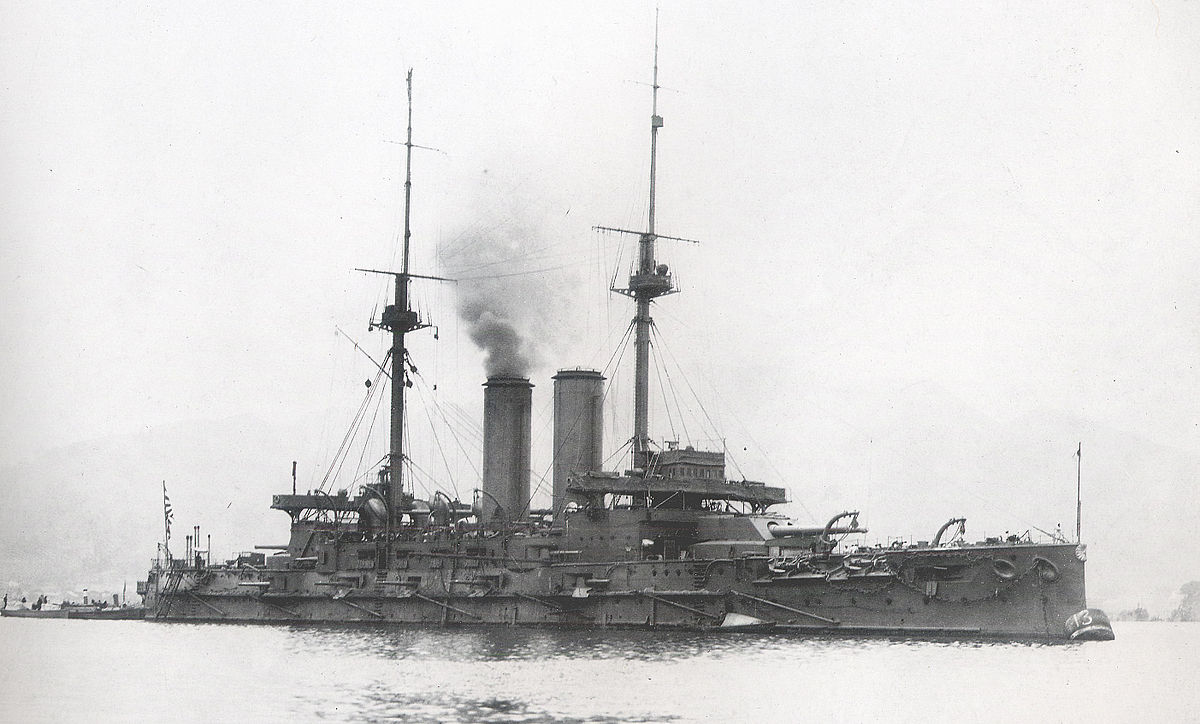

Featured Image: Print shows, in the foreground, a Russian battleship exploding under bombardment from Japanese battleships; a line of Japanese battleships, positioned on the right, fire on a line of Russian battleships on the left, in a surprise naval assault on the Russian fleet at the Battle of Port Arthur (Lüshun) in the Russo-Japanese War. (Torajirō Kasai/Wikimedia Commons)