Guest post for Chinese Military Strategy Week by Paul Pryce

There is much of concern in China’s Military Strategy white paper released by the Chinese Ministry of National Defense in May 2015. In particular, the notion of active defense extolled in the document arguably poses a far greater threat to the stability of the Asia-Pacific region than the reinterpretation of Article 9 in Japan’s Constitution. Coupled with other recent developments in the formulation and expression of China’s defense policy, there is a startling willingness to resort to the threat of force in order to resolve disputes. In July 2015, a meeting of the Central Military Commission announced that the People’s Liberation Army Air Force (PLAAF) requires a stealth-capable strategic bomber with a minimum range of 8,000 kilometers and the capacity to carry a payload of more than 10 tons of air-to-ground munitions. Although this envisioned replacement to the Xian H-6K bomber would still have a range and payload capacity less than the Northrup Grumman B-2 Spirit that has been in service with the United States Air Force (USAF) for almost two decades as of this writing, the extended range would allow China’s bomber fleet to reach as far as Guam or Japan’s Northern Territories, also known as the Kuril Islands.

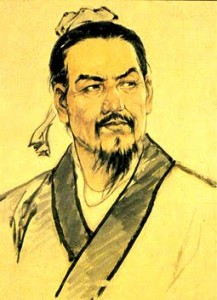

This saber-rattling can be explained in part by examining a school of thought that has risen to prominence together with the People’s Republic of China’s fifth generation of leadership, of which Xi Jinping is a part. Since Mao Zedong, Chinese leaders such as Deng Xiaoping and Jiang Zemin promoted the virtues of Confucianism and frequently quoted from Confucian works in their public remarks. With an emphasis on community-mindedness and obligations to the authority of the state, Confucius seemed to offer the philosophical justification for the entrenchment of the Communist Party of China in all areas of Chinese life. But there has been a noticeable departure from this tradition under Xi Jinping, who has relied heavily upon references to the works of Han Feizi.

Believed to have lived from 280 to 233 BC, Han Feizi was one of the founding thinkers of Legalism, a meritocratic ideology that came into being during the Warring States period of China’s history and was formally adopted by the victorious Qin state. Han Feizi has been called China’s Machiavelli, concerned more so with the efficiency of the state than with any over-arching moral or ethical questions. One passage from Han Feizi’s essay “The Eight Villainies,” a quote the fifth generation of leadership has apparently taken to heart, reads, “It is customary with a ruler that, if his state is small, he will do the bidding of larger states, and his army is weak, he will stand in fear of stronger armies. When the larger states come with demands, the small state must consent; when stronger armies appear, the weak army must submit.” Han Feizi does not comment on whether the doctrine of might makes right ought to be; he simply regards it as a natural and unavoidable consequence of a system in which different actors hold varying levels of power. There is also no apparent role for soft power in Han Feizi’s worldview – the strength of a ruler and his state is directly tied to military strength.

The memory of foreign occupation looms large for many Chinese leaders. In 2010, a diplomatic spat emerged when Chinese officials asked visiting British dignitaries to remove their poppies, worn to commemorate Remembrance Day and the Commonwealth’s war dead, because it allegedly reminded them of the Opium Wars. Xi Jinping himself often evokes the century of humiliation and the supposed role of the Communist Party of China in restoring national independence. If we regard Chinese history from the 1840s to the 1940s in the Legalist context, China was made subservient because it was militarily weak in relation to global powers like the United Kingdom, France, Russia, the United States, and others. If the weak must do the bidding of the strong and China is militarily weak in comparison to American hyperpower, the conventional thinking among the members of the Central Military Commission is that the gap must be closed or else it will only be a matter of time before the United States dictates to China once again.

One need not look far for examples of this anxiety about the capability gap. Xu Qiliang, the vice chairman of the Central Military Commission, wrote in 2013 that the People’s Liberation Army cannot currently meet the needs of national security and requires rapid modernization to contend with “the world’s advanced militaries”. Even though China already possesses the means to deter military aggression from any of its neighbors, it is apparent that the fifth generation of leadership still regards China as vulnerable unless it has an equivalency to every tool in the United States’ security toolbox. After all, it is telling that Xu Qiliang does not regard China as one of the world’s advanced militaries even though the PLAAF’s contingent of Xian H-6K bombers places China in a very exclusive club – only the United States, the Russian Federation, and the United Kingdom can also boast having strategic bombers at their disposal.

It is also worth noting how the presentation of the most recent Chinese Military Strategy reflects Han Feizi’s thought. In another of his works, The Difficulties of Persuasion, Han Feizi writes that, “If you wish to urge a policy of peaceful coexistence, then be sure to expound it in terms of lofty ideals, but also hint that it is commensurate with the ruler’s personal interests.” Just as the white paper advances the ideas of active defense and bottom-line thinking, it also emphasizes China’s commitment to participating in United Nations peacekeeping missions, the role of the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) in counter-piracy efforts in the Gulf of Aden, and appeals to such values as “the peaceful settlement of disputes.” This reflects a growing awareness on the part of Chinese officials that the rest of the world is paying attention to what kind of actor China might become in the 21st century. The message, in many respects, is that the Chinese Dream is inclusive – other nations and societies can benefit from China pursuing its own national interests, such as the investment and increased security that might come to Djibouti through the proposed establishment of a PLAN base there.

It is vital that those studying or interacting with Chinese policymakers to consider the historical context for China’s policies and their ideological framework. The China threat narrative considers Chinese strategy within a strictly neo-realist prism that supposes conflict will inevitably arise from a shift in polarity in international politics. Rather, Xi Jinping and Xu Qiliang can be best understood by consulting Han Feizi. As such, the explicit reference to China in the United States’ most recent maritime strategy, A Cooperative Strategy for 21st Century Seapower, might not help matters. It indicates to the Chinese political leadership that Han Feizi’s view of international politics endures more than two millennia later – the strong will continue to dictate to the weak, and so the United States will continue to determine the outcome of any territorial dispute in the South China Sea or East China Sea so long as the capability gap with China persists. An appeal to lofty ideals in the U.S.-China relationship, rather than explicit reference to geopolitical changes, could have spoken to the fifth generation of leadership on a deeper level without alienating the US’ Asia-Pacific allies. For its part, the National Military Strategy of the U.S. released in June 2015 goes some way toward accomplishing this, balancing criticism of China’s actions in the South China Sea with assertions that the U.S. “support[s] China’s rise.”

It may be that the revised maritime strategy adopts a harsher tone toward China in order to generate political will among other countries to participate in what the original Cooperative Strategy termed the Global Maritime Partnership. By distinguishing the U.S. from China as far as adherence with international maritime law is concerned, the U.S. Navy demonstrates that it can be a more reliable partner than PLAN to such countries as the Philippines and Vietnam. Nonetheless, with China participating meaningfully in the Rim of the Pacific Exercise (RIMPAC) and other multilateral venues, there must be consistency in the message delivered by the U.S. at the strategic, tactical, and operational levels. Security in the Asia-Pacific region will not benefit from mixed signals delivered by any actor.

Paul Pryce is Political Advisor to the Consul-General of Japan in Calgary and a Research Analyst at the Atlantic Council of Canada. The views expressed in this article are his own.