“The past isn’t dead. It isn’t even past.” – William Faulkner.

The crisis in Ukraine highlights a shortcoming in materialist theories, and a derivative shortcoming in our foreign policy process: the rhetorical battle between Russia and Ukraine is presently jumping across eleven hundred years of history, invoking symbols and identities from at least five different eras simultaneously into the present. Our policy-making ‘now’ is the last election, while the Russians and Ukrainians are all drawing on a millennium-long ‘now’ in their argument with each other. We are missing most of what is being said with our myopic lens, and much of what ‘power’ means hinges on these identity questions.

First, two ideas from academic literature help explain what’s happening.

– ‘Master Cleavage’ – Stathis Kalyvas describes how local leaders invoke larger narratives to address local issues during civil wars. What is presently happening is a dynamic, inside-out version of that process. There are any of a number of potential historical cleavages, depending on which pieces of the past are more present at any given time. For instance, to energize Ukrainian nationalists, the Red-and-Black flag of the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA) speaks of fierce resistance to both Soviets and Fascists during the Second World War. However, the UPA treated Poles brutally between Ukraine and Poland, so the Ukrainians would greatly prefer to decouple the UPA from their framing with Poland, and instead situate that relationship within the era of Soviet Occupation. What era is present, and with whom, is a key aspect of the current struggle. Whoever builds a better pastiche of history gets to choose the identity frame.

– ‘Polychronic’ Cultures – The ability to navigate this space hinges on a culture’s mode of interacting with the past. Hall, in his work on culture, describes two broad views of time – monochronic, where a culture experiences the flow of time as a linear progression of events, and polychronic, where a culture experiences multiple timeframes in parallel. In a monochronic culture, the past is ‘how we got here,’ but it’s not ‘here.’ In a polychronic culture, the past is ‘here’ in different ways for different things. The United States foreign policy process is explicitly monochronic. While many of those who inhabit that process are polychronic, ideas from these frames rarely last long in institutions to whom they are foreign. This is a problem when trying to understand polychronic identity struggles.

Second, since history is a battlefield of this present crisis, here’s a quick and semi-humorous video crash course on Russian history. There are at least five eras currently in play – these are horribly over-simplified, and I highly recommend reading a proper history on them.

First, the Kievan Rus’is the most fundamental identity dispute between Russia and Ukraine. The Rus’ was first identifiable state of the Eastern Slavs (Russia, Ukraine, Belarus,) the Kievan Rus’ was founded by Vikings in the 9th Century AD, and lasted until the 13th Century, when it was destroyed by the Mongols. During this time, the Rus’ converted to Christianity and aligned themselves with Constantinople. This was a golden age of sorts, at least in memory, and both Russia and Ukraine claim the mantle of the Kievan Rus’. Russia’s claim derives from being the strongest successor state to the Rus’, and from an influx of immigration following the Mongol conquest. In this version, Moscow leads the eventual resistance to the Mongols, and evolves as a Eurasian state. In the course of this evolution, strength and autocracy become necessary defenses; the consolidation of power under the Czars and the concomitant management of rebels is the natural state of play.

Ukraine’s claim derives from geography – Kiev was the leading city of the Rus.’ In this, the Rus’ provided a source for deep Ukrainian national identity – in the 1990s, the Ukrainian state shifted toward the hrivna currency, the same name as that of the Rus’, and the Trident symbol was a royal seal of the leaders of the Rus’. Soviet historiography declared the Kievan Rus as a feudal state, in order to fit a dialectical materialist model of history, while Ukrainian historians generally see the Rus’ as a proto-republic, proto-capitalist confederation. From this retelling, Moscow served as tax collectors to the Mongols, and the increasingly powerful city-state drifted toward autocracy. Therefore, the corruption of Yanukovych hearkens to the Mongol yoke, and the natural orientation of the Rus’ is toward Europe.

A second frame is the 16th to 18th Century Cossacks, and their conflicts with both the Polish-Lithuanian commonwealth and the Russian Czars. This was a tremendously tumultuous period for all parties involved, and too complicated to meaningful recount here. In present memory, the Cossack culture of freedom and their Hetman leaders provide identity markers for Ukraine, and a basis for the rejection of autocracy. Conversely, this was a ‘time of troubles’ for Moscow, and the Russians the Cossacks more as raiders and bandits. What this period means for modern interpretations of Ukrainian identity vis-à-vis their neighbors depends greatly on the interpretation of this time – the Cossacks alternatively supported and fought almost all of their neighbors during this period.

The Second World War provides the third frame for this argument. As described before, the Ukrainian Insurgent Army’s (UPA) red-and-black banner was a common sight in EuroMaidan – this is a direct challenge to the Russian leadership, who transpose onto the Soviet Union in this frame. The Soviets were deeply invested in framing the UPA as Fascist collaborators; while it is difficult to capture the entirety of a guerilla movement, the UPA described themselves as at war with both Soviets and Nazis. In the current struggle, Putin continues using the Soviet frame, with Russia Today describing the Ukrainians as neo-Nazis. (This echoes a refrain from Yugoslavia – the preferred anti-Croatian slur referred to a WWII collaborationist government.) The general Ukrainian framing takes the UPA at its word and sees it as a nationalist movement. Interestingly, in present memory, the UPA’s symbols have become more inclusive than the UPA itself likely was. The UPA’s hallmark phrase, ‘Slava Ukraini, Heroyam Slava,’ (Glory to Ukraine, Glory to her heroes,) is now being applied to the protestors killed in Kyiv’s Independence Square during the recent protests – East and West Ukrainian alike.

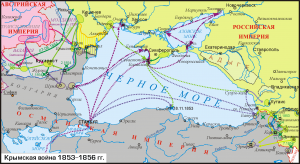

The Communist domination of Eastern Europe, in particular the Soviet interventions into Prague and Budapest, provides the most useful frame for the Ukrainian to reach out to their immediate Western neighbors. Framing the Soviet invasion of the Crimea in these terms invokes these memories amongst the Poles, Bulgarians and Romanians. For obvious reasons, the Russian government has little to gain from invoking this era, and their narratives steer clear of it.

Finally, the most recent memory frame is the chronological present and the contrast between the European Union and the Russian-led Eurasian Union. This is the frame best understood by our policy process, but it is misleading to view the previous eras as prologue rather than present. Note that the flags from these eras fly alongside each other – these symbols are all invoked in parallel. To some extent, all nations use parallel symbols, but what is particularly fascinating here is that the Ukrainians are making multiple identity bids to different eras all at once.

How does all of this matter? First, in this case, materialist approaches actually turn on identity. Russia obviously overmatches Ukraine in any sort of a tank-count. But it is a quite different overmatch if the Russians pin the Ukranians in the 17th Century as the rebellious Zaporozhian Cossacks fighting the Tsar than if Kiev traps the Putin in the 10th Century by claiming the mantle of the Kyivskaya Rus’ against the Mongol thralls of Muscovy. If this is the story of the Ukrainian language against the dominion of Greater Russia, then East Ukraine is properly on the Russian side of the struggle; in this story, the Ukrainians would be fighting on Russian turf until they reached Kyiv, and defections of Russophone units should be common. Conversely, if this is about the idea that the greater Rus’ is by its nature both European and free, then command and control becomes far easier for Kyiv, and Russian supply lines in Donetsk or Khar’kov would find themselves under partisan attack. The realist tank-count turns on the remarkably fluid identity contest.

Second, we cannot interpret many of the actions of either side without access to these texts and without the understanding that they run in parallel. Most dramatically, the battle over the mantle of the Kievan Rus’ has profound implications over the significance of the outcome of this crisis. If the Ukrainians can sustain the argument that descendants of the Rus’ aren’t inherently predisposed to autocracy, this immediately links to Belarus and even Russia itself. If the Ukrainians can do so in a way that fully incorporates East Ukraine in the project, then Putin’s irredentist strategies turn back on him, and Russophone Ukrainians become a visible threat to the narrative he is advancing.

To this point, the hub of Ukrainian nationalism, Lviv, spontaneously chose to speak Russian for a day a few days ago in a show of solidarity with East Ukraine. Donetsk, the easternmost major city in Ukraine, reciprocated by speaking Ukrainian for a day. The now-famous Colonel Mamchur of the Ukrainian Air Force, who marched his unit back onto their base, similarly demurred from ethnic chauvinism:

“It makes no sense. I can’t even say whether I am Ukrainian or Russian – it’s not a choice any of us can really make. My wife’s Belarusian, her mother is Russian. We’ve all got relatives on both sides,” said Col Mamchur. “When all this started we got calls from friends in Moscow who were simply in shock.” “Belarus, Russia, and Ukraine are really one Slavic people,” said the Colonel. “The divisions are only formalities. Whoever gave the order for this operation set brother against brother. It’s a crazy situation.”

This is potentially far more important than naval bases and the Black Sea fleet.

Note that in the Euromaidan protests, the previous Belarusian flag flew alongside the Ukrainian flag and the EU flag, and the Ukrainians are using a Belarusian protest rock song from as an anthem. (The lyrics are hardly ‘Winds of Change’ – the chorus goes, roughly, “Warriors of the Light.” The band actually played for EuroMaidan last December.) Moreover, the phrase ‘Slava Ukraina, Zhivye Belarus’ pops up fairly often in the comments section of viral videos from EuroMaidan supporters – “Glory to Ukraine, Long Live Belarus’.” These phrases and symbols are attempting to harmonize these different eras, all in the present – a spray painted trizub symbol [photo] speaks to this idea. At least in part, the identity challenge is intertwined with the strategic challenge; ‘who are we’ is as much a battleground as ‘what do we want.’

Our monochronic, rationalist, materialist foreign policy process deals well with answering the latter question. We have a deep problem, especially when dealing with peoples adept at harmonizing polychronic time rather than sequencing monochronic moves, in dealing with the former question. Recalling the painful market transitions of the 1990s, along with the technical economic issues, nations that synthesized liberal reforms into their national identity found the social capital to continue through difficult times. Poland was ideologically committed to reform, and was able to persist in part because of this. These reforms were generally presented as ‘Western,’ in contrast to a ‘traditional’ model in Russia. Mining the past would have perhaps provided deeper national connections to these projects – it is always easier to rediscover your golden age (even if you have to update it a bit) than to accept someone else’s vision of who you should be. Doing so requires skill and knowledge, but not a tremendous amount of cost.

Similarly, in the counter-terror world, we generally took al-Qaeda’s word for what the Caliphate looked like. Bin Laden was no Salah ad-Din, and Zawahiri is laughably distant from an Averroes or an Avicenna. The Caliphate was, in many ways, a customs union and an empire of trade; through this lens, Dubai is a more legitimate successor to the Caliphate than anything that al-Qaeda built in the mountains of Afghanistan. We should have contested the past rather than agreeing to our adversary’s framing by presenting the future in its stead.

While mastering the mechanics of polychronic time requires far more than a simple transpose, we cannot afford to be blind to the present memory of history nor deaf to the symbols through which that history is contested. We certainly cannot afford to do so in this conflict, where history is so present in the present. At least amongst the Rus’, the past is hardly past.

Dave Blair is an active duty officer in the United States Air Force and a PhD student at Georgetown University. The views expressed are of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the Air Force, the DoD or the U.S. government.