By Geoffrey L. Irving

Introduction

A combination of the United States’ nascent modern industrial policy, diplomacy, and aligned governmental and commercial interests have set the conditions for it to pull ahead in the race to control vital telecommunications infrastructure in the Pacific. The race to control telecommunications infrastructure is founded upon a number of small island nations and territories in the Pacific Ocean that last saw global attention during the island-hopping campaigns of the Second World War. This analysis will give particular focus to the nations and territories of Guam and the Solomon Islands and the effect that they have on subsea telecommunications infrastructure. Further, this analysis will review how competing American and Chinese telecommunication infrastructure strategies are affecting these Pacific Island nations and territories and how the convergence of the United States’ regulatory regimes, including “Team Telecom,” and commercial interests are dominating Pacific telecommunications.

The People’s Republic of China’s (hereinafter referred to as “China”) return to great power status is well-covered in national security circles and beyond. From construction of artificial islands in the South China Sea, to continued saber rattling directed at Taiwanese unification, to the infiltration of Chinese technology into the United States’ supply chains and defense industrial base, media and academic coverage of China’s return to global power often include dire warnings that the United States is unknowingly falling behind. However, there is one sector of Sino-American competition that currently bodes well for the United States and its allies, and deserves additional recognition and analysis; namely, the race to control international telecommunications infrastructure, and specifically the subsea fiber-optic cables that serve as the backbone of modern communication.

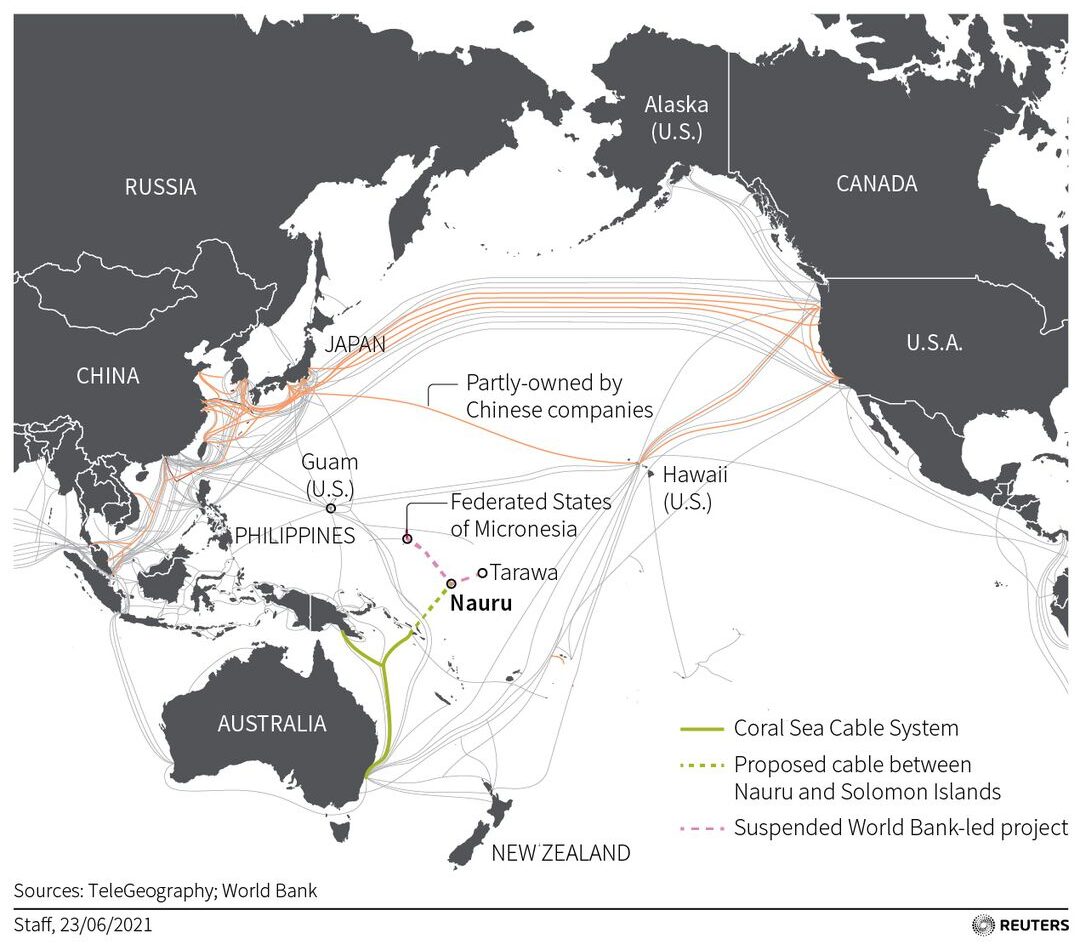

Subsea communications infrastructure is the backbone of the modern way of life. More than 95 percent of international internet traffic flows across subsea fiber-optic cables.1 This data traffic includes all types of communications, from consumer phone calls, to streaming entertainment, financial transactions, or secure military or intelligence messaging.2 While high-profile satellite communications like those provided by SpaceX’s Starlink low earth orbit technology receive a lot publicity for their deployment in austere conditions, satellite data capabilities do not come close to matching the data capacity of fiber-optic cables.3

The concept of a subsea cable is relatively simple. Since the first subsea copper telegram cable was laid by the Atlantic Telegraph Company in 1858 between the North America and Ireland, cable technology has progressively matured with advances in materials science and information technology, although the operational concept has remained the same.4 A physical cable is spooled into the hull of a massive ship designed specifically for the task of laying and maintaining subsea cables.5 The ship then steams from one landing site across a body of water to another, laying cables and signal amplification units along the way. The cable, with its periodic amplifiers, sinks to the seafloor where it rests on top of seabed topography and uses relative obscurity and layers of armored sheathing to protect the delicate strands of glass fibers that carry light waves across thousands of miles.6 A tremendous level of complexity is required to execute this task; however, this simple explanation is meant to provide a basic understanding of the operations behind a subsea fiber-optic cable.

As the largest body of water in the world by far, the Pacific Ocean poses a particular challenge when laying subsea cables. Before the first Pacific subsea cable existed, reaching East Asia by electronic communication required either unreliable radio repeaters subject to the vagaries of weather and atmospheric conditions, or through a cable route that travelled across the Atlantic, through Cape Town, South Africa or Russia to a connecting cable to Japan or India.7 However, since the first Pacific cable was laid in 1903, cables across the Pacific have proliferated and now serve as the primary means to connect isolated Pacific Island Nations to the rest of the world.8 Additionally, in a bi-polar geopolitical environment internet connectivity and infrastructure is a key tool in drawing these nations towards alignment with the United States or China.9

Cable infrastructure is such an important piece of the geopolitical chessboard because its ownership and control can influence global data traffic and the contents of that traffic. Of particular note, as an overwhelming majority of financial transactions are negotiated, administered, and settled via electronic communications, if a party controls communications infrastructure, it can control the financial dealings of any client who relies on that infrastructure.10 For small Pacific Islands Countries, having a single cable connecting an island to the world wide web creates a single point of failure that can have extremely dire consequences if there is an unanticipated fault or break in the line – as there often are in subsea infrastructure.11 For example, in January 2022, an underwater volcanic eruption and landslide severed the only subsea cable connecting the island nation of Tonga to the outside world. As a result, it was nearly impossible to contact the island for a number of weeks.12

China’s return to superpower status on the global stage has been accompanied by its audacious Belt and Road Initiative.13 This program funded massive infrastructure programs around the developing world to expand China’s diplomatic reach and to erode the international institutions of the post-Second World War international order. As a subset of the Belt and Road Initiative, China specifically focused on future technologies and set a goal to create a “Digital Silk Road” that would involve communication infrastructure projects driven by Chinese national champion state owned enterprises like Huawei and China Unicom.14 These projects were intended to include both the provision of 5G-capable network infrastructure for developing nations as well as subsea communications infrastructure to connect partner nations to China’s internet service providers. To this end, Huawei, an electronics hardware conglomerate, established Huawei Marine in 2009 to begin providing marine communications technology hardware and infrastructure services.15 Huawei Marine, as a newcomer to the maritime communications technology industry, had to compete with established Western companies like SubCom and Alcatel Submarine Networks to build and maintain subsea infrastructure.16

While the United States and its allies did not have the appetite to compete with China’s massive spending spree in the developing world, an alignment of government and commercial interests has led it and other western-aligned countries to dominate the communications landscape in the Pacific. As of this writing, no Chinese-owned or operated subsea cable is the sole provider for subsea communications to any Pacific Island.17 Further, networks generally reject any Huawei and other Chinese state-owned-enterprise communications and network hardware.18 This outcome bodes well for American interests in the Pacific, and the expanded provision of network capabilities to Pacific Island countries and territories will have beneficial economic impacts on local economies. In the following section, this paper will analyze case studies of Guam and the Solomon Islands as it relates to the competition of US and Chinese telecommunications providers and the expansion of Pacific telecommunications networks.

Case Study: Guam

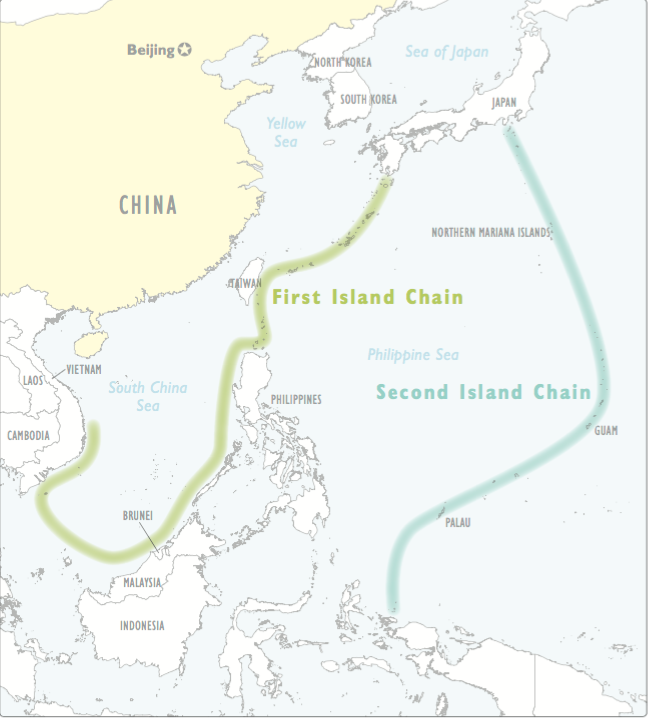

Guam is a small Pacific Island that is the southernmost island in the Mariana Island chain and is the largest island in Micronesia.19 Guam has a rich history of indigenous culture and position in contemporary history as a strategic way point in the Pacific Ocean for competing navies. Guam was a protectorate of the United States Navy following the end of the Spanish-American war in 1898 and then received formal recognition as an unincorporated territory with self-rule in 1950.20 Guam is also home to a large American military presence and hosts a U.S. Naval Base, an Air Force Air Field, and a burgeoning Marine Corps Base. Because it is the United States’ westernmost territory, Guam is also a landing point for many trans-Pacific cables, earning it the moniker “The Big Switch in the Pacific.”

The first transpacific cable landed on Guam in 1904 by a private enterprise led by John Mackay. This cable functioned until 1950 when a fault removed it from service leaving decades of inconsistent telecommunications connectivity until the advent and proliferation of fiber-optic cables. Following the advent of fiber-optic cables, there was an explosion of telecommunication activity on Guam evident by the laying of sixteen cables between 1987 and 2022 – roughly one cable every two years.21 See Figure 1.

| Cable System Name | Year | Status |

| TPC-3 | 1987 | Retired |

| GPT | 1990 | Retired |

| PacRim West | 1995 | Retired |

| Mariana-Guam (MICS) | 1997 | Currently lit |

| GP | 1999 | Retired 2011 |

| Australia-Japan | 2001 | Currently lit |

| China-US | 2001 | Retired 2016 |

| Tata TGN Pacific | 2002 | Currently lit |

| Asia-America Gateway | 2009 | Currently lit |

| PPC-1 | 2009 | Currently lit |

| HANTRU1 | 2010 | Currently lit |

| Guam Okinawa Kyushu Incheon | 2013 | Currently lit |

| Atisa | 2017 | Currently lit |

| SEA-US | 2017 | Currently lit |

| Japan-Guam-Australia North | 2020 | Currently lit |

| Japan-Guam-Australia South | 2020 | Currently lit |

| Echo | 2023 | Planned, not lit |

| Apricot | 2024 | Planned, not lit |

| Bifrost | 2024 | Planned, not lit |

| Asia Connect Cable 1 (ACC-1) | 2025 | Planned, not lit |

Figure 1: A historic list of telecommunication cables landing on Guam

Despite sixteen cables laid on Guam over the past three decades, Guam’s telecommunications market is relatively small. Guam’s population is around 170,000 people, roughly the same as a midsized American city like Springfield, Missouri.22 Despite this small market, three competing internet and communications service providers compete for market share on the island – Docomo, IT&E, and GTA. As of 2017, Guam had an internet penetration rate of eighty-one percent among its population.23 As a US territory that hosts a large military footprint, Guam’s telecommunications network is largely insulated from Chinese intrusion. Measures such as Federal government regulation, import controls, and the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) largely block Chinese or Chinese-funded companies from penetrating the Guamanian telecommunications sector.24

Further, as a result of Guam’s strategic position as a gateway to Asia and wider trends in the telecommunications sector, many large US technology companies are vying to invest in data centers in Guam.25 These data centers will serve as edge storage and computing nodes for internet service providers with retail and commercial customers in the Indo-Pacific theater. This next wave of telecommunications infrastructure poses an additional benefit to Guam’s local economy, as the influx of investment to stand up data centers that rely on consistent power generation and stable climate will likely create increased opportunities for job growth and a local telecommunications expertise.

Because of these reasons, Guam’s role as the “Big Switch in the Pacific” has been a driver of its local economy and will likely continue to yield dividends as the telecommunications industry matures and seeks improved and additional infrastructure projects. Additionally, as the United States focuses its national security posture on the Pacific theater, Guam will likely see increased military investment which has both positive and negative effects on local culture, but inarguably injects additional capital into the small island.

Case Study: The Solomon Islands

A study of the Solomon Islands’ telecommunications infrastructure and geopolitical position is an interesting counterpoint to Guam. Unlike Guam, the Solomon Islands is a sovereign nation state comprised of hundreds of islands off the East coast of Papua New Guinea and Northwest of Australia.26 The Solomon Islands have a population of approximately 700,000, but a gross domestic product of only $1.6 billion.27 Compared to Guam’s population of 170,000 and 2021 GDP of $5.8 billion, an apparent disparity exists as the Solomon Islands trails Guam’s development and productivity in terms of per capita GDP. Additionally, the Solomon Islands had an internet penetration rate of only 12% in 2017, and reportedly around 30% in 2022.28 While Guam serves as a switch for a growing inventory of subsea cables, the Solomon Islands is served by only one cable, the Coral Sea Cable (installed in 2020), which connects four of its major islands to New Guinea and Australia.29

To maintain a neutral position in the Sino-American competition for influence in the South Pacific, the Solomon Islands previously courted foreign investments and partnerships from the party willing to make them. The Coral Sea Cable reveals how the competition between China and US-aligned nations plays out over competition to build telecommunications infrastructure.

In 2018, the Solomon Islands government announced a partnership with China’s Huawei Technology Company to install a maritime fiber-optic cable that would link the islands to its two major neighbors: Papua New Guinea and Australia.30 This infrastructure project was long overdue, as high-speed internet was not available to an overwhelming majority of Solomon islanders. When the Solomon Islands announced the partnership with Huawei, US and Australian diplomats identified the risk that Huawei hardware and software could pose to Australia’s telecommunications network and began pushing the Solomon Islands to reconsider the partnership.31 Ultimately, the Australian government financed construction of the Coral Sea Cable by providing $92 million dollars in funding.32 Australia’s commitment, alongside diplomatic pressure from Japan and the United States, blocked Huawei from installing a new fiber-optic system connecting Pacific Island countries and further pushed the balance of power towards US-aligned nations in the Pacific telecommunications race. Unfortunately, these same pressures did not stop Papua New Guinea from completing its own domestic fiber-optic cable in partnership with Huawei Maritime Tech Co. in 2019.33

Although the Solomon Islands government ultimately partnered with Australia and the Australian firm Vocus to lay the Coral Sea Cable, the Solomon Island government has continued to court Chinese infrastructure investment. In 2019, the Solomon Islands formally ceased diplomatic relations with Taiwan, possibly to ensure future close diplomatic ties to the PRC. Then, in 2022, the Solomon Islands again announced a partnership with Huawei to build 161 mobile transmission towers financed by a $66 million loan from China’s Export Import Bank.34 The project has an expected completion date of November 2023, with the goal of installing most of the towers before Solomon Islands hosts the Pacific Games. Australia and other Pacific partners have again voiced opposition and concern about Huawei’s integration into the Solomon Islands’ local telecommunications infrastructure.35

The Solomon Islands’ diplomatic posturing between both Chinese and Australian/US-aligned investment gives it negotiating power to derive maximum investment from all sides. Its government cannot be criticized for attempting to upgrade the country’s telecommunications infrastructure to connect its population and drive GDP growth. However, negotiators should see the consistent playbook of courting Chinese investment and pressuring Australia and Pacific nations to step in with additional funding. While this means that Huawei and China are still in the race for dominance of Pacific telecommunications infrastructure, the Coral Sea Cable project shows that nations will choose US-aligned nations when given the opportunity. Therefore, it is up to the United States and its allies to create the opportunities to do so.

The United States’ Pacific Policy Response

A broad decoupling of American and Chinese industries has been the theme of the early 2020s. For example, equity markets demanded audit transparency of Chinese firms listed in the United States and threatened to delist noncompliant companies.36 Further, the Foreign Investment Risk Review Modernization Act of 2018 strengthened the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS) and gave the federal government broad power to mitigate or block adversarial investment or ownership in industries sensitive to The United States’ national security.37 With additional authorities, CFIUS has been increasingly aggressive and encouraged by members of Congress to investigate and block specific transactions. In CFIUS’ shadow however, there is a smaller interagency committee that receives less media coverage but is largely responsible for ensuring United States telecommunications resiliency and for winning the telecommunications competition in the South Pacific. That committee is the Committee for the Assessment of Foreign Participation in the United States Telecommunications Services Sector (Team Telecom). This Committee’s name does not have a phonetic acronym and is referred to simply as “Team Telecom.”

Team Telecom is an interagency committee chaired by the Department of Justice that includes the Departments of Defense and Homeland Security.38 Executive Order 13913 established Team Telecom in April 2020. The Committee provides the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) with recommendations on whether to issue licenses to companies applying to provide telecommunications services or otherwise connect to the domestic US telecommunications network.39 This scope includes licenses to provide cable-based international telecommunications transport services, licenses to provide satellite communications, and multiple other FCC licenses.

When the FCC receives an application for a new cable landing or for the transfer existing assets to a foreign purchaser, the FCC will refer the transaction to Team Telecom for review by the Departments of Justice, Homeland Security, and Defense to ensure that national security interests will not be affected or compromised by the foreign owner. If Team Telecom sees undue risk to domestic consumer data or to secured government data traffic traveling over a particular cable system, the members then recommend that the FCC deny the license or grant the license with specific conditions to mitigate the national security risk.40 In effect, this collaborative effort has succeeded in sealing out adversarial actors from the United States telecommunications sector, and shielded the United States telecommunications industry from Chinese competition and associated risks.

Because the United States controls strategic switching points in the Pacific, namely American Samoa, Guam, and Hawaii, Team Telecom’s rules regarding network hardware manufacturers and cyber security standards apply to any cable that lands in those territories. Because these territories are situated at geographically strategic points in the Pacific, Team Telecom’s rulings have become the de facto standard for the Pacific maritime telecommunications industry. While CFIUS is garnering headlines by protecting American technology and forcing adversary finance from core aspects of the United States’ domestic economy, Team Telecom operates quietly to both preserve the integrity of the United States’ domestic telecommunications network as well as set the conditions for US-aligned telecommunications companies to dominate network infrastructure across the Pacific Ocean.

The proliferation of Pacific subsea telecommunication cables is not a product of government policy alone. Rather, the information technology explosion of the past two decades and the demand for near-instant communication and connectivity to markets around the world created a huge demand for telecommunications capacity. The volume of cables landing on Guam in Figure 1 captures the frenetic pace of construction and expansion of bandwidth connecting North America to Asia. Furthermore, advances in materials science allowed fiber-optic cables to carry increasing volumes of data. The MICS cable, installed in 1997 that connects the Mariana Island chain, provides an estimated bandwidth capacity of 622 Megabytes per second, while Google’s Apricot cable is projected to have the capacity to run 190 Terabytes per second (190,000,000 Megabytes per second), or just over 300,000 times the throughput of the MICS cable.41 Despite exponential increases in data transport capabilities, infrastructure cables have continuously struggled to keep pace with industry demands for transport service. A trend away from consortia construction of fiber-optic lines in the telecommunications industry is one of the results of data transport demand so quickly outstripping supply.

In the early stages of large fiber-optic cable projects, international consortia of telecommunication infrastructure companies, government organizations, and occasionally research organizations primarily funded and planned new cable lines. In 2007, a consortium of 19 different parties funded the Asia American Gateway cable and laid 20,000 kilometers of fiber-optic cable from the United States, through Guam, to South Pacific nations like Singapore, Thailand, and the Philippines.42 The Australia-Japan cable, laid in 2009, was funded through a consortium of five telecommunications companies – Communications Global Network Services Ltd, NTT Ltd, Softbank Corp., Telstra, and MFC Globenet, Inc.43 This trend of consortium ownership was necessary to secure the required licenses and regulatory approvals to run and maintain new cables across multiple jurisdictions, as well as to diversify financial risk across a number of different owners. However, a new trend has emerged. Technology “hyperscalers” like Meta (formerly Facebook), Google, and Amazon are now unilaterally, or bilaterally, building and controlling their own cables.

Over the past few years, technology conglomerate hyperscalers announced projects that will install and operate their own series of subsea fiber-optic cables. These hyperscalers have been overwhelmingly American and are creating the next wave of telecommunications infrastructure that will be primarily influenced by US legislation and governmental policy. Hyperscalers are interested in building and owning their own infrastructure so that they get primary right of transport on the cable, instead of having to negotiate and pay for leases on competitor or legacy cables. Google and Meta plan to run two new cables, Echo and Bifrost, through Guam to diverse landing points in the Pacific.44 Additionally, Google plans to create the Apricot Cable to extend Google Cloud services to markets that complement Echo and Bifrost’s reach.45 These cables will have the net effect of increasing internet connectivity and lowering latency for large swaths of under-connected Pacific populations.46 The ancillary effect is that these hyperscalers are all primarily US corporations, subject to US regulation and therefore prohibited from contracting with or connecting to many Chinese telecommunications providers. While US technology champions are on a building spree, China’s technology champions and state-owned enterprises like HMN Technologies (formerly known as Huawei Maritime Networks) do not have plans to build any comparable trans-Pacific cables. With the United States’ alignment of commercial demand and governmental industrial policy, fiber-optic cables have and will continue to proliferate in the Pacific, creating net benefit to both isolated Pacific Island Countries and the United States.

Conclusion: The United States is Winning the Pacific Telecom Race

The United States is particularly well suited to win the contest to dictate and control operations, standards, and installation of new telecommunications infrastructure in the Pacific. As discussed, the United States’ control of key geographic islands like Hawaii and Guam gives it an upper hand when seeking to run transpacific fiber-optic cables. As “The Big Switch in the Pacific,” Guam is well situated as the landing point of choice for the next generation of transpacific cables that will effectively seal out Chinese telecom competitors from the Pacific subsea infrastructure market. The US Team Telecom’s oversight and regulation, in addition to associated federal industrial policies, has effectively increased critical telecommunications infrastructure resiliency and set a standard for new infrastructure projects in the Pacific. This beneficial status quo is reflected in the relationship between island nations such as the Solomon Islands and the United States and its allies. While Pacific Island Countries like the Solomon Islands will continue to entertain Chinese technology investment, case studies like the Coral Sea Cable show that these nations will elect Western infrastructure programs when given the opportunity. Finally, the geopolitical competition to connect the Pacific is a massive net benefit for Pacific Island Countries’ populations. Competitive and redundant communications infrastructure mean that the number of nations and islands that rely on single points of failure for their communications will diminish over time as future cable projects propagate. On a geopolitical note, the race to build and operate Pacific telecommunications infrastructure is a bright spot for the United States and a valuable case study in how governmental policy and commercial opportunity can interact to protect American interests and extend necessary and beneficial services to the global community.

Geoffrey Irving works with the Office of the Undersecretary of Defense, Acquisition and Sustainment to protect the Defense Industrial Base. Geoff previously served on active duty with the U.S. Marine Corps, and is currently a Major in the United States Marine Corps Reserve. Geoff is a graduate of Tsinghua University College of Law and writes about the national security implications of international economic competition.

The views expressed in this paper are those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Department of Defense or the U.S. Government.

References

[1] 2013 Section 43.82 Circuit Status Data, FCC International Bureau Report, Federal Communications Committee (July 2015)

[2] Ibid.

[3] Micah Maidenberg, “Elon Musk’s SpaceX, Pentagon to Deepen Ties Despite Dispute on Starlink Funding in Ukraine,” Wall Street Journal, October 20, 2022, https://www.wsj.com/articles/elon-musks-spacex-pentagon-to-deepen-ties-despite-dispute-on-starlink-funding-in-ukraine-11666270801; Ibid.

[4] Allison Marsh “The First Transatlantic Telegraph Cable was a Bold Beautiful Failure” IEEE Spectrum, (October 31 2019), https://spectrum.ieee.org/the-first-transatlantic-telegraph-cable-was-a-bold-beautiful-failure

[5] Justin Sherman, “Cyber Defense Across the Ocean Floor: The Geopolitics of Submarine Cable Security” Atlantic Council Snowcroft Center for Strategy and Security, Cyber Statecraft Initiative (September 2021)

[6] Ibid.

[7] “Honolulu’s First Cable” Evening Bulletin, December 5, 1902.

[8] Bill Burns “Submarine Cable History” SubmarineCableSystems.com, 2012. https://www.submarinecablesystems.com/history

[9] Justin Sherman, “Cyber Defense Across the Ocean Floor: The Geopolitics of Submarine Cable Security” Atlantic Council Snowcroft Center for Strategy and Security, Cyber Statecraft Initiative (September 2021)

[10] Ibid.

[11] Amanda Watson, “The Limited Communication Cables for Pacific Island Countries,” Asia-Pacific Journal of Ocean Law and Policy, vol 7, 2022

[12] Ibid.

[13] U.S. Library of Congress, CRS, China’s 14th Five-Year Plan: A First Look, by Karen Sutter and Michael Sutherland, CRS Report IFI1684 (Washington, DC: Office of Congressional Information and Publishing, January 5, 2021).

[14] Ibid.

[15] Thomas Blaubach “Connecting Beijing’s Global Infrastructure: The PEACE Cable in the Middle East and North Africa,” MEI Policy Center (March 2022)

[16] “Submarine Fiber Cable Market Size to Grow by USD 3.86 Bn at a CAGR of 11.04%| Investments Source Segment is expected to witness lucrative growth,” Technavio Research (May 27, 2022): https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/submarine-fiber-cable-market-size-to-grow-by-usd-3-86-bn-at-a-cagr-of-11-04-investments-source-segment-is-expected-to-witness-lucrative-growth–technavio-301555740.html

[17] “HMN Tech,” Submarine Cable Map, TeleGeography, accessed November 13, 2022; https://www.submarinecablemap.com

[18] Amy Remeikis, “Australia supplants China to build undersea cable for Solomon Islands,” The Guardian, June 13, 2018

[19] “Guam,” The World Factbook, U.S. Central Intelligence Agency, accessed November 13, 2022

[20] Ibid.

[21] “Guam,” Submarine Cable Map, TeleGeography, accessed November 13, 2022; https://www.submarinecablemap.com

[22] “Population, total – Guam” Data, The World Bank, accessed November 13, 2022; https://data.worldbank.org/country/GU

[23] “Individuals using the Internet (% of population) – Guam” Data, The World Bank, accessed November 13, 2022; https://data.worldbank.org/country/GU

[24] Donald Trump, Executive Order 13913, “Establishing the Committee for the Assessment of Foreign Participation in the United States Telecommunications Services Sector.” Federal Register 85, no. 19643 (April 4, 2022): https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2020/04/08/2020-07530/establishing-the-committee-for-the-assessment-of-foreign-participation-in-the-united-states

[25] David Abecassis, Dio Teo, Goh Wei Jian, Michael Kende, Neil Gandal, “Economic Impact of Google’s APAC Network Infrastructure,” Anlysys Mason (September 2020)

[26] “Solomon Islands,” The World Factbook, U.S. Central Intelligence Agency, accessed November 13, 2022

[27] “Population, total – Solomon Islands” Data, The World Bank, accessed November 13, 2022; https://data.worldbank.org/country/solomon-islands

[28] “Individuals using the Internet (% of population) – Solomon Islands” Data, The World Bank, accessed November 13, 2022; https://data.worldbank.org/country/solomon-islands; Georgina Kekea, “Solomon Islands secures $100m China loan to build Huawei mobile towers in historic step,” The Guardian, (August 18, 2022)

[29] “Solomon Islands,” Submarine Cable Map, TeleGeography, accessed November 13, 2022; https://www.submarinecablemap.com

[30] Amy Remeikis, “Australia supplants China to build undersea cable for Solomon Islands,” The Guardian, June 13, 2018

[31] Colin Packham, “Ousting Huawei, Australia finishes laying undersea internet cable for Pacific allies,” Reuters, (August 27, 2019), https://www.reuters.com/article/us-australia-pacific-cable/ousting-huawei-australia-finishes-laying-undersea-internet-cable-for-pacific-allies-idUSKCN1VI08H

[32] Australian High Commission Papua New Guinea, “Coral Sea Cable System launched”. Accessed November 13, 2022; https://png.embassy.gov.au/pmsb/1148.html#:~:text=Construction%20of%20the%20cable%20system,Guinea%20and%20Solomon%20Islands%20governments.

[33] Corinne Reichert, “PNG sticks with Huawei for subsea cable: Report” ZD Net Magazine, November 26, 2018; https://www.zdnet.com/article/png-sticks-with-huawei-for-subsea-cable-report/

[34] Georgina Kekea, “Solomon Islands secures $100m China loan to build Huawei mobile towers in historic step,” The Guardian, (August 18, 2022)

[35] Ibid.

[36] Matthew P. Goodman, “Unpacking the PCAOB Deal on U.S.-Listed Chinese Companies,” Center for Strategic & International Studies, (September 28, 2022)

[37] Foreign Investment Risk Review Modernization Act of 2018, US Code 50 (2018), § 4565

[38] Donald Trump, Executive Order 13913, “Establishing the Committee for the Assessment of Foreign Participation in the United States Telecommunications Services Sector.” Federal Register 85, no. 19643 (April 4, 2022): https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2020/04/08/2020-07530/establishing-the-committee-for-the-assessment-of-foreign-participation-in-the-united-states

[39] Ibid.

[40] “The Committee for the Assessment of Foreign Participation in the United States Telecommunications Services Sector – Frequently Asked Questions” National Security Division, United States Department of Justice, accessed November 13, 2022; https://www.justice.gov/nsd/committee-assessment-foreign-participation-united-states-telecommunications-services-sector

[41] Federal Communications Commission. “In the Matter of Micronesian Telecommunications Corporation, Application for a license to land and Operate a High Capacity Digital Submarine Cable System Extending Between the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands and Guam,” File No. S-C-L-92-003, February 3, 1993. https://transition.fcc.gov/ib/pd/pf/scl_doc/93-91.pdf; Nico Roehrich “Apricot subsea cable will boost internet capacity, speeds in the Asia-Pacific region” Engineering at Meta, August 15, 2021; https://engineering.fb.com/2021/08/15/connectivity/apricot-subsea-cable/

[42] “About Us’ Asia American Gateway, accessed November 13, 2022; https://asia-america-gateway.com/AboutUs.aspx

[43] “Staff & Shareholders” Australia Japan Cable, accessed November 13, 2022; https://ajcable.com/ajc-network/staff-shareholders/

[44] Bikash Koley, “This bears repeating: Introducing the Echo subsea cable,” Google Cloud Blog, March 29,2021, https://cloud.google.com/blog/products/infrastructure/introducing-the-echo-subsea-cable

[45] Ibid.

[46] Bikash Koley, “Announcing Apricot: a new subsea cable connecting Singapore to Japan,” Google Cloud Blog, August 16, 2021; https://cloud.google.com/blog/products/infrastructure/new-apricot-subsea-cable-brings-more-connectivity-to-asia

Featured Image: APRA HARBOR, Guam (March 5, 2016) An aerial view from above U.S. Naval Base Guam (NBG) shows Apra Harbor with several navy vessels in port. (U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 3rd Class Deven Ellis/Released)