By Benjamin Claremont

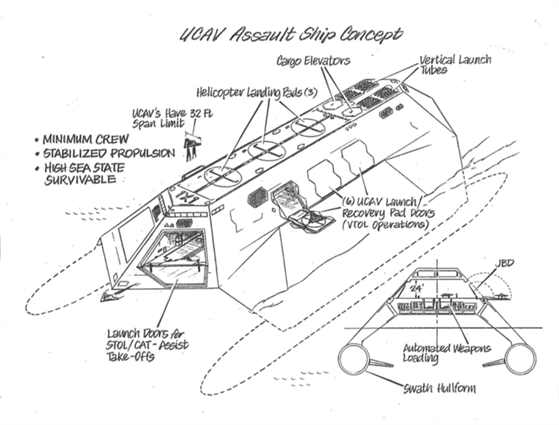

In a recent article titled “Is the Moskva-Class Helicopter Cruiser the Best Naval Design for the Drone Era?” author Przemysław Ziemacki proposed that the Moskva-class cruiser would be a useful model for future surface combatants. He writes, “A ship design inspired by this cruiser would have both enough space for stand-off weapons and for an air wing composed of vertical lift drones and helicopters.”1 These ships would have a large battery of universal Vertical Launch Systems (VLS) to carry long range anti-ship missiles and surface-to-air missiles. The anti-ship missiles would replace fixed-wing manned aircraft for strike and Anti-Surface Warfare (ASuW), while surface-to-air missiles would provide air defense. Early warning would be provided by radar equipped helicopters or tilt-rotor aircraft, while vertical take-off UAVs would provide target acquisition for the long range missiles. A self-sufficient platform such as “a vessel inspired by the Moskva-class helicopter carrier and upgraded with stealth lines seems to be a ready solution for distributed lethality and stand-off tactics.” The article concludes that inclusion of this type of vessel in the US Navy would make “the whole fleet architecture both less vulnerable and more diversified.”

The article’s foundation rests on three principles: aircraft carriers are, or will soon be, too vulnerable for certain roles; manned naval aviation will be replaced by shipboard stand-off weapons; and drones have fundamentally changed warfare. From these principles the article proposes a more self-sufficient aviation cruiser would be less vulnerable in enemy Anti-Access/Area Denial (A2/AD) zones and able to effect “sea denial” over a large area of ocean, becoming an agile and survivable tool of distributed lethality, rather than “a valuable sitting duck.”2 Both the foundational principles and the resulting proposal are flawed.

The article names itself after the Moskva-class. They were the largest helicopter cruisers, but like all helicopter cruisers, were a failure. They were single-purpose ships with inflexible weapons, too small an air group, too small a flight deck, and awful seakeeping that magnified the other problems. Their planned role of hunting American ballistic missile submarines before they could launch was made obsolete before Moskva was commissioned: There were simply too many American submarines hiding in too large an area of ocean to hunt them down successfully.

The article’s ‘Modern Moskva’ proposal avoids the design’s technical failures but does not address the fundamental flaws that doomed all helicopter cruisers. Surface combatants such as cruisers, destroyers and frigates need deck space for missiles, radars, and guns. Aviation ships need deck space for aircraft. Fixed-wing aircraft are more efficient than rotary-wing, and conventional take-off and landing (CTOL) – particularly with catapults and arresting gear – more efficient than vertical take-off and landing (VTOL). Trying to make one hull be both an aviation vessel and a surface combatant results in a ship that is larger and more expensive than a surface combatant, but wholly worse at operating aircraft than a carrier.

Consequently, helicopter cruisers were a rare and fleeting type of surface combatant around the world. Only six of these ungainly hybrids were ever commissioned: France built one, Italy three, the Soviet Union two. The Japanese built four smaller helicopter destroyers (DDH).3 In every case the follow-on designs to these helicopter ships were dedicated aircraft carriers: the Soviet Kiev-class, Italian Giuseppe Garibaldi-class*, and Japanese Hyuga-class. France’s Marine Nationale chose not to replace Jeanne d’Arc after her 2010 retirement.

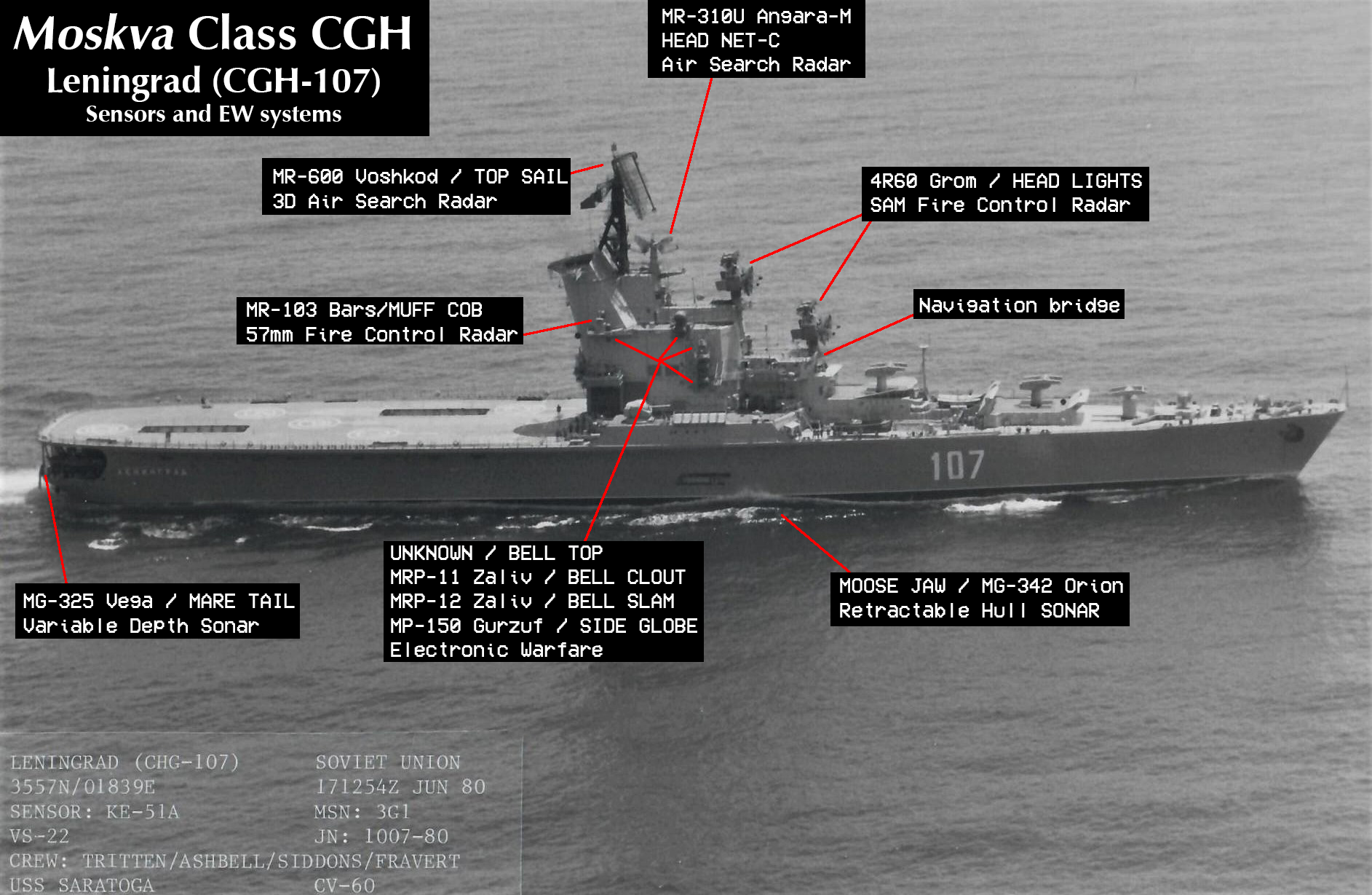

The Moskva-class was a striking symbol of Soviet Naval Power. These vessels epitomize the aesthetic of mid-Cold War warship with a panoply of twin arm launchers, multiple-barrel anti-submarine rocket-mortars and a forest of antennae sprouting from every surface save the huge flight deck aft. They are also poorly understood in the West. The Soviets were never satisfied with the design, cancelling production after the first two ships in favor of dedicated separate aircraft carriers and anti-submarine cruisers, the 6 Kiev and Tblisi-class carriers and 17 Kara and Kresta-II-class ASW cruisers in particular.4

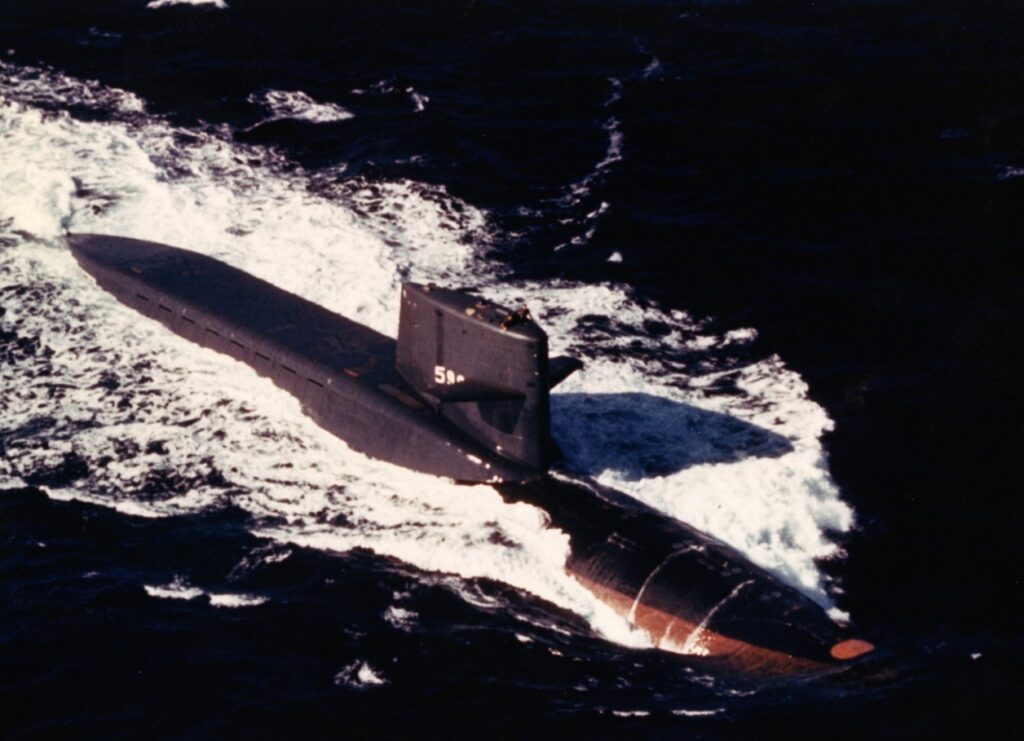

The Moskva-class, known to the Soviets as the Проект 1123 “Кондор” Противолодочная Крейсера [Пр.1123 ПКР], (Project 1123 “Condor” Anti-Submarine Cruiser/Pr.1123 PKR) was conceived in the late 1950s. Two ships, Moskva and Leningrad, were laid down between 1962 and 1965, entering service in late 1967 and mid 1969 respectively. The Moskva-class was conceived as anti-submarine cruisers, designed to hunt down enemy SSBN and SSN as part of offensive anti-submarine groups at long ranges from the USSR.5 The primary mission of these groups was to sink American ballistic missile submarines, the 41 for Freedom, before they could launch.6

The requirements were set at 14 helicopters to enable 24/7 ASW helicopter coverage, and a large number of surface to air missiles for self-protection. The resulting ships were armed with (from bow to stern):7

- 2x 12 barrel RBU-6000 213mm ASW rocket-mortars

- 96 Depth Bombs total, 48 per mount

- 1x Twin Arm SUW-N-1 (RPK-1) Rocket-Thrown Nuclear Depth Bomb system

- 8 FRAS-1 (Free Rocket Anti Submarine) carried

- 2x twin-arm launchers for SA-N-3 GOBLET (M-11 Shtorm)

- 48 SAM per mount, 96 total

- 2x twin 57mm gun mounts, en echelon

- 2x 140mm ECM/Decoy launchers (mounted en echelon opposite the 57mm guns)

- 2x quintuple 533mm torpedo mounts amidships

- One per side, 10 weapons carried total

This concept and armament made sense in 1958, when submarine-launched ballistic missiles had short ranges and SSBNs would have to approach the Soviet coast.8 In 1964 the USN introduced the new Polaris A-3 missile, which extended ranges to almost 3,000 miles.9 By the commissioning of Moskva in December 1967, all 41 for Freedom boats were in commission, with 23 of those boats carrying the Polaris A-3.10 The increased range of Polaris A-3 meant that US SSBNs could hit targets as deep in the USSR as Volgograd from patrol areas west of the British Isles, far beyond the reach of Soviet ASW forces.11 The Project 1123 was obsolete in its designed mission before the ships took to sea, as they could never find and destroy so many submarines spread over such a large area before the SSBNs could launch their far-ranging missiles.

The defining feature of the Moskva-class was the compliment of 14 helicopters kept in two hangars, one at deck level for two Ka-25 (NATO codename: HORMONE) and a larger one below the flight deck for 12 more of the Kamovs. The greatest limitation of this hangar and flight deck arrangement was the relative inefficiency compared to a traditional full-deck carrier. There was only space on the flight deck to launch or recover four aircraft at any one time. This was sufficient for the design requirements, which were based around maintaining a smaller number of aircraft round-the-clock. However, the limited space prevents efficient surging of the air group, and the low freeboard forced central elevators, rather than more efficient deck edge designs. The Soviet Navy found the aviation facilities of the Moskva-class limited and insufficient for its role.12 The third ship in the class was to be built to a differing specification, Project 1123.3, 2000 tons heavier, 12m longer and focused on improving the ship’s air defenses and aviation facilities.13 Project 1123.3 was cancelled before being laid down and focus shifted to the more promising Project 1143, the four ship Kiev-class aircraft carriers.

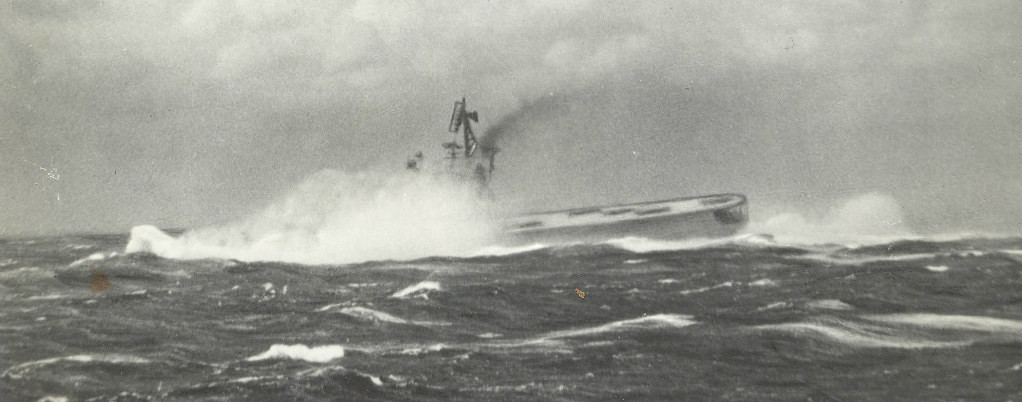

Among the chief reasons for the cancellation of all further development of the Moskva-class was the design’s terrible seakeeping. The very fine bow pounded in rough seas, shipping an enormous amount of water over the bow.14 On sea trials in 1970, Moskva went through a storm with a sea state of 6, meaning 4-6m (13-20ft) wave height calm-to-crest. For the duration of the storm the navigation bridge 23m (75 ft) above the waterline was constantly flooded.15

The Moskva-class also had a broad, shallow, round-sided cross-section aft. This caused issues with roll stability in all but moderate seas. This meant that flight operations could be conducted only up to a sea-state of 5, or 2.5-4m (8-13 ft) waves, especially when combined with the excessive pounding in waves.16 In addition, the class shipped so much water over the bow that the weapons suite was inoperable in heavy seas and prone to damage at sea state 6.17 The Moskva-class failed to meet the requirements for seakeeping set by the Soviet Navy.18 It could not effectively fight in bad weather, a fatal flaw for ships designed to hunt enemy submarines in the North Atlantic.

Project 1123 stands among the worst ship classes put to sea during the Cold War. The Moskva-class had too few aircraft, too small a flight deck, poorly laid out weapons, shockingly bad seakeeping, and was generally unsuitable for operation in regions with rough seas or frequent storms, despite being designed for the North Atlantic. They were not significantly modernized while in service and were scrapped quickly after the Soviet Union collapsed. Many knew the Moskva-class cruisers were bad ships when they were in service. The Soviets cancelled not only further construction of the class, but further development of the design before the second ship of the class, Leningrad, had commissioned.19 In place of Project 1123 the Soviets built Project 1143, the Kiev-class, an eminently more sensible, seaworthy, and efficient ship with a full-length flight deck which saw serial production and extensive development.20

Part II: Whither the Helicopter Cruiser?

Having explored the development and history of the Moskva-class helicopter cruiser, let’s examine the proposed ‘Modern Moskva’. The goal of the ‘Modern Moskva’ is to have a self-contained ship with drones, helicopters, stand-off anti-ship and strike weapons, and robust air defenses.21 The original article calls this a helicopter cruiser (CGH), helicopter carrier (CVH), or helicopter destroyer (DDH). This article will describe it as an aviation surface combatant (ASC), which better reflects the variety of possible sizes and configurations of ship. The original article then explains that such a self-contained ship accompanied by a handful of small ASW frigates (FF) would be the ideal tool for expendable and survivable distributed lethality to carry out sea denial in the anti-access/area denial zones of America’s most plausible enemies.22 Both the design and operational use concept are flawed, and will be examined in sequence.

The argument made in favor of aviation surface combatants in the article rests on three fundamental principles: that the threat of anti-shipping weapons to carriers has increased, that naval aircraft will be supplanted by long-range missiles, and that unmanned and autonomous systems have fundamentally changed naval warfare. These foundational assertions are false.

The threat of anti-ship weapons has increased over time, in absolute terms. Missile ranges have increased, seekers have become more precise, and targeting systems have proliferated, but the threat to aircraft carriers has not increased in relative terms. As the threat to aircraft carriers has increased, shifting from conventional aircraft to both manned (Kamikaze) and unmanned anti-ship missiles, the carrier’s defenses have also become more powerful. The Aegis Combat System and NIFC-CA combine the sensors and weapons of an entire naval task force, including its aircraft, into one single coherent system. Modern navies are also transitioning towards fielding fully fire-and-forget missiles, such as RIM-174 ERAM, RIM-66 SM-2 Active, 9M96, 9M317M, Aster 15/30, and others. Navies are also moving towards quad-packed active homing missiles for point defense, such as RIM-162 E/F/G ESSM Block 2, CAMM and CAMM-ER, or 9M100. These two developments radically increase the density of naval air defenses, pushing the saturation limit of a naval task force’s air defenses higher than ever before.

The article is correct that anti-ship weapons have become more capable, but the defenses against such weapons have also benefited from technological advances. The aircraft carrier is no more threatened today than has been the case historically. That is not to say that aircraft carriers are not threatened in the modern era, but that they always have been threatened.

The article claims that naval fixed-wing aircraft will soon be supplanted in their roles as stand-off strike and attack roles by long range missiles. While it is true that modern missiles can strike targets at very long ranges, naval aircraft will always be able to strike farther. Naval aviation can do so by taking the same missiles as are found on ships and carrying them several hundred miles before launch. For example, an American aviation surface combatant as proposed in the article would carry 32 AGM-158C LRASM in VLS, and fire them to an estimated 500 nautical miles. A maritime strike package with 12 F-18E Super Hornets could carry 48 LRASM to 300 nautical miles, and then launch them to a target another 500 miles distant, delivering 150% of the weapons to 160% the distance.23 Unlike VLS-based fires, which must retreat to reload, carrier-based aircraft can re-arm and re-attack in short order. The mobility, capacity, and persistence of aircraft make it unlikely that naval aviation will be replaced by long range missiles.

Finally, the article claims that there is an ‘unmanned revolution’ which has fundamentally changed naval combat. This point has some merit, but is overstated. Unmanned systems typically increase the efficiency of assets, most often by making them more persistent or less expensive. However, this is not a revolution in naval warfare. There have been many technological developments in naval history that were called revolutionary. Other than strategic nuclear weapons the changes were, instead, evolutionary. Though they introduced new methods, new domains, or increased the mobility and tempo of naval warfare, these were evolutionary changes. Even with modern advanced technology, the strategy of naval warfare still largely resembles that of the age of sail. As Admiral Spruance said:

“I can see plenty of changes in weapons, methods, and procedures in naval warfare brought about by technical developments, but I can see no change in the future role of our Navy from what it has been for ages past for the Navy of a dominant sea power—to gain and exercise the control of the sea that its country requires to win the war, and to prevent its opponent from using the sea for its purposes. This will continue so long as geography makes the United States an insular power and so long as the surface of the sea remains the great highway connecting the nations of the world.”24

Control or command of the sea is the ability to regulate military and civilian transit of the sea.25 This is the object of sea services. Unmanned and autonomous systems enhance the capability of forces to command the sea, but they do not change the principles of naval strategy.

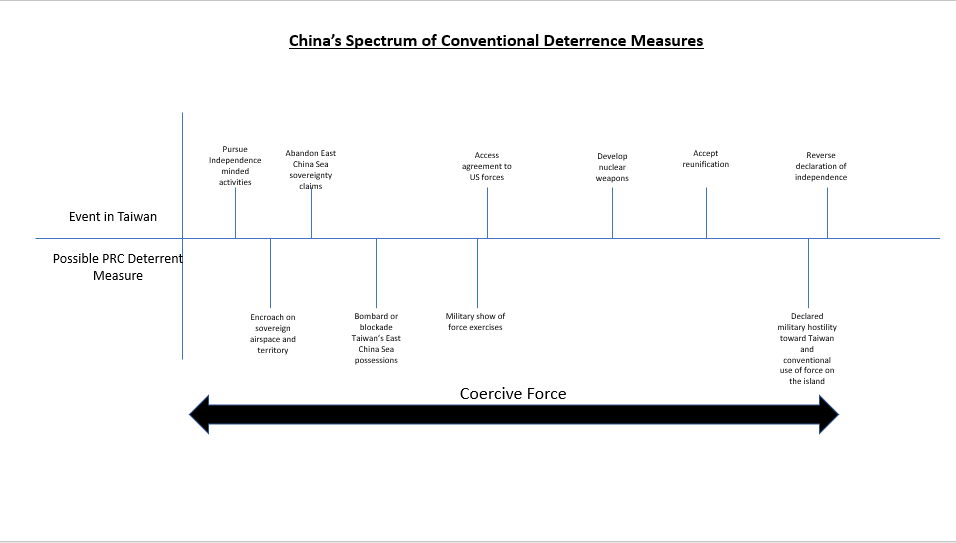

Having examined the underlying assumptions of the article, we must now examine how these ships are proposed to be used. The concept is that task groups of “two of the proposed helicopter carriers and at least 3 ASW frigates… would be most effective… [in] the South-West Pacific Ocean and the triangle of the Norwegian Sea, the Greenland Sea and the Barents Sea.”26 These waters are said to be so covered by enemy anti-access/area denial (A2/AD) capabilities that “traditional air-sea battle tactics” are too dangerous, requiring these helicopter cruisers groups to change the risk calculus.

The article’s use case for the aviation surface combatant has three interlocking assertions. First is that China and Russia will use A2/AD. A2/AD refers to “approaches that seek to prevent US forces from gaining or using access to overseas bases or critical locations such as ports and airfields while denying US forces the ability to maneuver within striking distance of [the enemy’s] territory.”27 Next, that A2/AD represents a novel and greater threat to naval forces which prevents typical naval tactics and operations, therefore new tactics and platforms are needed. Finally, that aviation cruisers leading frigates into these A2/AD zones for various purposes are the novel tactic and platform to solve A2/AD.

The article is flawed on all three counts. Despite the popularity of A2/AD in Western literature, it does not actually correlate to Russian or Chinese concepts for naval warfare. Even if A2/AD did exist as is proposed, it does not represent a relatively greater threat to naval task forces than that historically posed by peer enemy forces in wartime. Finally, even if it did exist and was the threat it is alleged to be, the solution to the problem would not be helicopter cruiser groups.

A2/AD is a term which evolved in the PLA watching community and has been applied to the Russians.28 Indeed, there is no originally Russian term for A2/AD because it does not fit within the Russian strategic concept.29 Russian thinking centers around overlapping and complimentary strategic operations designed “not to deny specific domains, but rather to destroy the adversary’s ability to function as a military system.”30 While there has been a spirited back-and-forth discussion of the capabilities of Russian A2/AD systems, these center around “whether Russian sticks are 4-feet long or 12-feet long and if they are as pointy as they look or somewhat blunter.”31 By ignoring the reality of how the Russian military plans to use their forces and equipment this narrative loses the forest for the trees.

The term A2/AD comes from PLA watching, perhaps it is more appropriate to the PLAN’s strategy? Not particularly. The Chinese concept is a strategy called Near Seas Defense, “a regional, defensive strategy concerned with ensuring China’s territorial sovereignty and maritime rights and interests.”32 Defensive refers to the goals, not the methods used. The PLAN’s concept of operations stresses offensive and preemptive action to control war initiation.33 Near Seas Defense has been mixed with the complimentary Far Seas Protection to produce A2/AD.34 As with the Russian example, the actual strategy, operational art and tactics of the PLA have been subsumed into circles on a map.

If A2/AD existed as more than a buzzword it would not necessarily pose a new or greater threat to aircraft carriers than existed historically. The Royal Navy in the Mediterranean and the US Navy off Okinawa and the Japanese Home Islands during the Second World War experienced threats as dangerous as A2/AD. The constrained waters in the Mediterranean, especially around Malta, kept Royal Navy forces under threat of very persistent air attack at almost all times. At Okinawa and off the Home Islands, the Japanese could launch multi-hundred plane Kamikaze raids against exposed US forces thousands of miles from a friendly anchorage. These raids were the impetus for Operation Bumblebee, which became Talos, Tartar and Terrier and eventually the Standard Missiles and Aegis Combat System.35 The US Navy has been aware of and striving to meet this challenge for nearly a century, just under different names.

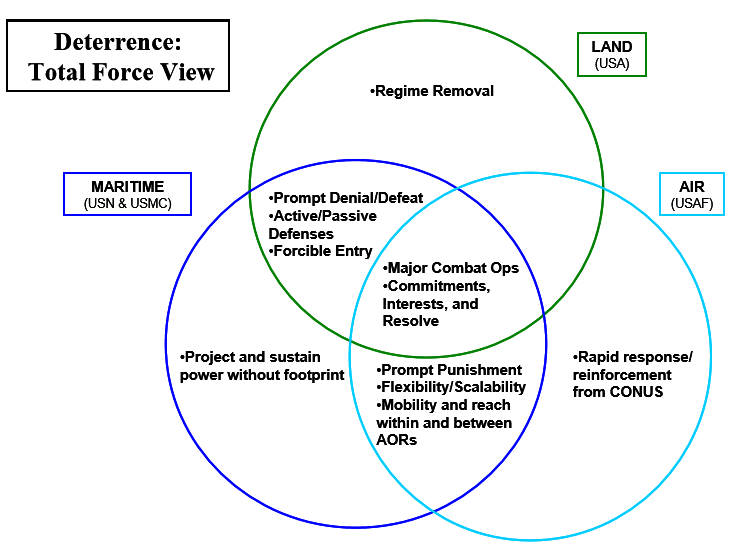

Since 1945, the defense has required:

- Well-positioned early warning assets, such as radar picket ships or aircraft,

- Effective fighter control,

- Large numbers of carrier-based fighters relative to incoming launchers (shoot the archer) and weapons (shoot the arrow),

- Heavily-layered air defenses on large numbers of escorts and the carriers themselves. In the Second World War, these included 5”/38, 40mm, and 20mm anti-aircraft guns. Today, these include SM-2ER/SM-6, SM-2MR, ESSM, RAM, Phalanx, Nulka and SRBOC.

- Well-built ships with trained and motivated crews, skilled in fighting their ship and in damage control.

This methodology does not wholly prevent ships being lost or damaged: There is no such thing as a perfect defense. What it does do is optimize the air defenses of a task force for depth, mass, flexibility, and redundancy.

Aviation cruiser groups are not the appropriate solution to the A2/AD problem. The cruiser groups proposed have far less air defense than the US Navy’s Dual Carrier Strike Groups (DCSG), the current concept to push into “A2/AD” areas.36 The paper implies that these aviation surface combatants would be smaller targets and would not be attacked as much, but if they were attacked, they would be expendable. However, the enemy decides what targets are worth attacking with what strength, not one’s own side. If a carrier strike group with 48 strike fighters, 5 E-2D AEW&C aircraft to maintain 24/7 coverage, escorts with 500 VLS cells, and the better part of two dozen ASW helicopters is too vulnerable to enter the A2/AD Zone, why would two aviation cruisers and five ASW frigates with 200-350 VLS cells, some drones and 4 AEW helicopters be able to survive against a similar onslaught?37 If a carrier cannot survive the A2/AD area, deploying less capable aviation surface combatants would be wasting the lives of the sailors aboard. The rotary-wing AEW assets proposed are too limited in number and capability to provide anything approaching the constant and long-range coverage the USN feels is necessary.38 Even if A2/AD existed as the threat it is alleged to be, the proper response would not be to build helicopter cruisers and send them into harm’s way with a small ASW escort force. The appropriate response would be to build large numbers of competent escorts to reinforce the carrier task forces, such as the Flight 3 Burke-class or the forthcoming DDG(X).

Conclusion: Neither Fish Nor Fowl

The Moskva-class represented the largest and most obvious failure of the helicopter cruiser concept. Their weapons were inflexible and their air group too small, compounded by horrible seakeeping. Beyond the failings of the design itself, their doctrinal role was made obsolete before the first ship commissioned. While the proposed ‘Modern Moskva’ avoids these failings, the concept does not address the problems which doomed all helicopter cruisers. Efficiently operating large numbers of aircraft requires as much flight deck as possible. Surface combatants require deck space for weapons and sensors. Trying to combine the two requirements yields a ship that does neither well. A ‘Modern Moskva’ finds itself in a position of being larger and more expensive than a normal surface combatant, but wholly worse than a carrier at flight operations.

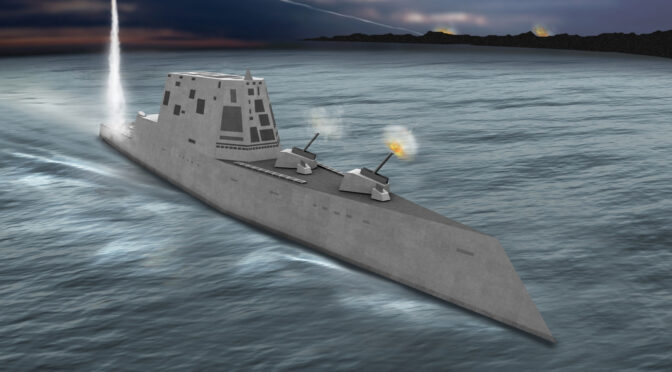

If the aircraft are necessary and supercarriers unavailable, then a light carrier (CVL) is a better solution. Specifically, this light carrier should be of conventional CATOBAR design with two catapults capable of operating two squadrons of strike fighters, an electronic attack squadron and an ASW helicopter squadron, plus detachments of MQ-25 and E-2D. In addition to the previously mentioned increased anti-shipping and land attack strike radius, the CVL’s fixed wing air group can fight the outer air battle, the modern descendant of the WWII-era “Big Blue Blanket,” and do so in excess of 550 nautical miles from the carrier.39 A task group with a single CVL and escorts could exercise command of the sea over a far greater area than a helicopter cruiser group, and do so with greater flexibility, persistence, survivability, and combat power. The range of carrier aircraft allows the carrier to stay outside of the purported A2/AD bubbles and launch full-capability combined arms Alpha strikes against targets from the relative safety of the Philippine or Norwegian Seas.

The world is becoming less stable. Russia and China are both militarily aggressive and respectively revanchist and expansionist. They are skilled, intelligent and capable competitors who should not be underestimated as potential adversaries. American and Allied forces must be ready and willing to innovate both in the methods and tools of warfare. Rote memorization, mirror imaging and stereotyping the enemy lead to calamity, as at the Battle of Tassafaronga. It is important to remember that these potential enemies are just as determined, just as intelligent, and just as driven as Western naval professionals. These potential enemies will not behave in accordance with facile models and clever buzzwords, nor will they use their weapons per the expectations of Western analysts. They have developed their own strategies to win the wars they think are likely, and the tactics, equipment and operational art to carry out their concepts.

English speaking defense analysis tends to obsess over technology, but war is decided by strategy, and strategy is a historical field.40 We must not forget that “The good historian is like the giant of a fairy tale. He knows that wherever he catches the scent of human flesh, there his quarry lies.”41 Historical context focuses on the human element of warfare: the persistent question of how to use the weapons and forces available to achieve the political goals of the conflict. By removing history, and with it strategy, operational art, and tactics, proposals often drift toward past failed concepts mixed with the buzzword du jour. War has only become faster and more lethal over time. The stakes in a conflict with the probable enemy will be higher than any war the US has fought since the Second World War. Novelty and creativity are necessary and should be lauded, but they must be balanced with historical context, strategic vision, and a candid and realistic understanding of potential adversaries.

Benjamin Claremont is a Strategic Studies MLitt student at the University of St Andrews School of International Relations. His dissertation, Peeking at the Other Side of the Fence: Lessons Learned in Threat Analysis from the US Military’s Efforts to Understand the Soviet Military During the Cold War, explored the impact of changing sources, analytical methodologies, and distribution schemes on US Army and US Navy threat analysis of the Soviet Military, how this impacted policy and strategy, and what this can teach in a renewed era of great power competition. He received his MA (Honours) in Modern History from the University of St. Andrews. He is interested in Strategy, Operational Art, Naval Warfare, and Soviet/Russian Military Science.

The appearance of U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) visual information does not imply or constitute DoD endorsement.

*Correction: The Italian carrier was of the Giuseppe Garibaldi class, not the Vittorio Veneto class as originally stated.

Endnotes

1. Przemysław Ziemacki, Is the Moskva-Class Helicopter Cruiser the Best Naval Design for the Drone Era?, CIMSEC, 7/9/2021, https://cimsec.org/is-the-moskva-class-helicopter-cruiser-the-best-naval-design-for-the-drone-era/

2. Ziemacki, Moskva Class for the Drone Era. All quotations in this and the preceding paragraph are from Mr. Ziemacki’s article.

3. The French Jeanne d’Arc, the Italian Andrea Doria, Caio Duilio, and Giuseppe Garibaldi, the Soviet Moskva and Leningrad, and the Japanese Haruna, Hiei, Shirane and Kurama.

4. Yuri Apalkov, Противолодочные Корабли, 2010, МОРКНИГА, p. 79, 98 The Tblisi class became the Kuznetsov class after 1991.

5. Apalkov, Противолодочные Корабли, p. 18

6. Apalkov, Противолодочные Корабли, p. 17

7. Apalkov, Противолодочные Корабли, p. 22,

8. USN Strategic Systems Programs, FBM Weapon System 101: The Missiles, https://www.ssp.navy.mil/fb101/themissiles.html#I

9. USN Strategic Systems Programs, FBM Weapon System 101: The Missiles, https://www.ssp.navy.mil/fb101/themissiles.html#I

10. The first to be built with Polaris A-3 was USS Daniel Webster, SSBN-626. In addition, the 10 SSBN-627 boats and 12 SSBN-640 boats all carried 16 Polaris A-3 each for a total of over 350 missiles.

11. Determined using Missilemap by Alex Wellerstein, https://nuclearsecrecy.com/missilemap/

12. Apalkov, Противолодочные Корабли, p. 28

13. Apalkov, Противолодочные Корабли, p. 28

14. Apalkov, Противолодочные Корабли, p. 28

15. Apalkov, Противолодочные Корабли, p. 28

16. Apalkov, Противолодочные Корабли, p. 28

17. Apalkov, Противолодочные Корабли, p. 28

18. Apalkov, Противолодочные Корабли, p. 28

19. Work was halted on Pr.11233 in 1968, Leningrad commissioned on June 22nd, 1969.

20. Yuri Apalkov, Ударные Корабли, МОРКНИГА, p. 4-6

21. Ziemacki, Moskva Class for the Drone Era.

22. Ziemacki, Moskva Class for the Drone Era.

23. Xavier Vavasseur, Next Generation Anti-Ship Missile Achieves Operational Capability with Super Hornets, USNI News, 12/19/2019 https://news.usni.org/2019/12/19/next-generation-anti-ship-missile-achieves-operational-capability-with-super-hornets

24. Adm. Raymond A. Spruance, quoted in Naval Doctrine Publication 1: Naval Warfare (2020), P. 0 accessible at: https://cimsec.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/NDP1_April2020.pdf

25. Julian Corbett, Some Principles of Naval Strategy, p. 103-4

26. Ziemacki, Moskva Class for the Drone Era.

27. Chris Dougherty, Moving Beyond A2/AD, CNAS, 12/3/2020, https://www.cnas.org/publications/commentary/moving-beyond-a2-ad (clarification in brackets added)

28. Michael Kofman, It’s Time to Talk about A2/AD: Rethinking the Russian Military Challenge, War on the Rocks, 9/5/2019, https://warontherocks.com/2019/09/its-time-to-talk-about-a2-ad-rethinking-the-russian-military-challenge/

29. Kofman, It’s Time to Talk about A2/AD. The Russian term is a translation of the English

30. Kofman, It’s Time to Talk about A2/AD

31. Kofman, It’s Time to Talk about A2/AD

32. Rice, Jennifer and Robb, Erik, “China Maritime Report No. 13: The Origins of “Near Seas Defense and Far Seas Protection”” (2021). CMSI China Maritime Reports, p. 1

33. Rice and Robb, CMSI #13, p. 7

34. For more on the interactions between Near Seas Defense and Far Seas Protection see RADM Michael McDevitt, USN (Ret.), Becoming a Great “Maritime Power”: A Chinese Dream, CNA, June 2016, https://www.cna.org/cna_files/pdf/IRM-2016-U-013646.pdf

35. The technical advisor for Bumblebee, 3T, Typhon, and Aegis was the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory, who also developed the VT fuse. https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/pdfs/ADA229872.pdf

36. USS Theodore Roosevelt Public Affairs, Theodore Roosevelt, Nimitz Carrier Strike Groups conduct dual carrier operations, 2/8/2021, https://www.cpf.navy.mil/news.aspx/130807

37. A nominal CSG has 1x CG-47 and 4x DDG-79; CGH group has 2x 96 Cell CGH and 5x ASW LCS or 5x FFG-62

38. This is due to the payload, fuel efficiency, speed and altitude limitations inherent to rotary wing or tilt-rotor aircraft compared to fixed wing turboprops.

39. Based on estimated combat radius of c. 500 nautical miles for the F-18E, plus 50 nautical miles for the AIM-120D.

40. Hew Strachan, ‘Strategy in the Twenty-First Century’, in Strachan, Hew, ed., The Changing Character of War, (Oxford, 2011) p. 503; A.T. Mahan, The Influence of Seapower on History, (Boston, 1918) p. 7, 226-7; Julian Corbett, Some Principles of Maritime Strategy, (London, 1911) p. 9, Vigor, ‘The Function of Soviet Military History’, in AFD-101028-004 Transformation in Soviet and Russian Military History: Proceedings of the Twelfth Military History Symposium, 1986 p. 123-124; Andrian Danilevich, reviewing M. A. Gareev M. V. Frunze, Military Theorist, quoted in Chris Donnelly, Red Banner: The Soviet Military System in Peace and War, p. 200

41. Marc Bloch, The Historian’s Craft, (New York, 1953), p. 26

Featured Image: April 1, 1990—A port beam view of the Soviet Moskva class helicopter cruiser Leningrad underway. (U.S. Navy photo by PH3 (Ac) Stephen L. Batiz)