By Daniel Thomassen

Germany’s assault on neutral Norway in April 1940 was swift and surprising. A great power was contemplating a smaller state with strategic importance, but without any significant defense capability and no credible allies. Fortress Norway ensured all-year access to the Atlantic for the Kriegsmarine, as well as iron ore transport for the German war industry. Extending the frontline to a secondary northern front put pressure on the crumbling British and French resistance on the European continent. The invasion of Norway was an act of brutal realism, where the comparative power of states and alliances within an anarchic international system is decisive for strategic decision making.

This writing discusses the deteriorating strategic environment that will challenge Norwegian security again in the coming decades, and the necessary responses to them. The Norwegian National Security Strategy must address these challenges by refocusing NATO, enhancing bilateral partnerships, and strengthening the Norwegian Armed Forces.

A New Dawn on the Arctic

Four reverberant strategic trends are converging to increase pressure on Russian neighbor Norway and NATO’s Arctic flank. First, climate change will gradually melt Arctic ice, opening a new ocean for shipping and competition for natural resources. Secondly, Russia will continue its confrontational line with the West, while strengthening its global power status through commercial and military activities in the High North and strategic cooperation with new Asian partners. The Russian loss of confidence in diplomacy and international law is a dangerous trajectory converging with increased Arctic competition. Third, the balancing power of the U.S. is gradually shifting its effort to the Asia-Pacific, while fiscal challenges necessitate a reduced footprint elsewhere. Finally, NATO is becoming relatively weaker because of decreasing European defense spending, American reluctance to cover the expenses, as well as divergent national interests and conflicting views on Article 5 collective response scenarios.

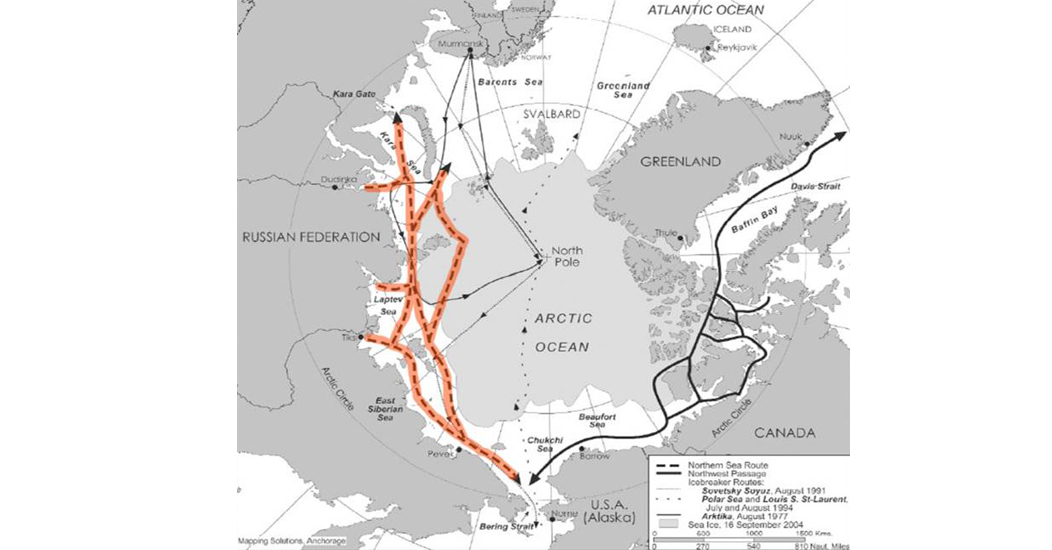

The world’s attention is now increasingly on the Arctic, where melting polar ice ensures access to new areas faster than previously expected. Global commercial shipping will gradually utilize new shipping lanes in the Arctic, which also holds an abundance of petroleum, gas, minerals, and important fish stocks. The leading nations of the world will increase their presence in the region and emphasize its access and security as a global maritime commons. The Northern Sea Route on the Russian coast is already open through July to December and normally ice-free in September and October. 71 vessels from 11 different nations used the passage in 2013. The travel between Western Europe and East-Asia can be reduced by two weeks when choosing this route. The Northwest-passage as well as the transpolar route will also become seasonally accessible in the 2020-2030 period.[2]

Studies suggest that a third of the world’s undiscovered natural gas is in the Arctic – mostly in the Russian sector.[3] Then, there are vast amounts of oil and minerals[4] with an estimated 13% of the world’s undiscovered oil resources and $2 trillion worth of important minerals like iron ore, zinc, nickel, gold, and uranium in the Russian sector. Even if the accessibility and technology have been unavailable to extract these resources safely and economically, such constraints are gradually overcome. Russia started oil production from the first Arctic field of Prirazlomnaya in December 2013[5] and recently increased its output. Exxon and Russian state-owned oil-company Rosneft only saw their cooperative effort to start production in the Kara-Sea interrupted because of sanctions on the Russian energy industry.

The Arctic nations are now racing for ownership of the valuable Arctic seabed. Russia and Denmark have already submitted overlapping claims to the UN Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf, and Canada is preparing to do the same. However, the Commission does not hold authority to decide ownership. Its statements will be the basis of bilateral negotiations, like the 2010 Barents Sea Treaty, which settled the delimitation between Russia and Norway. Significant Asian nations are also focusing their attention to the polar region. China, India, Japan, South Korea, and Singapore were all accepted as observer-nations in the Arctic Council in 2013. China is actively negotiating extensive commercial relations with the Arctic nations – with favorable export deals in return for Chinese investment and technology.

The interpretation of the Svalbard Treaty from 1920 and international law in adjacent maritime zones will become increasingly disputed as multinational activity in the Arctic increases. The most pressing concern will be threefold: whether Norway enjoys sovereign rights to resources buried in the continental shelf, whether it can claim taxes from other nations’ commercial activity, and finally whether the signatories have equal rights to extract these seabed resources.[6] Furthermore, Norwegian regulation on fishing as well as restrictions on drilling, extraction, and shipping for environmental protection will be challenged. Even if the other Arctic nations and the EU share Norway’s concern for responsible and sustainable activity, they will each weigh conflicting commercial and environmental interests separately.

Russia’s Rise and Requital

According to its strategies and doctrines, Russia is a major global power that must regain its temporarily lost historic and natural place as a counterbalance to the U.S. and the West in the international system. The Russian Federation regards the unipolar system with the U.S. solitary superpower as a serious threat to itself and other states with divergent forms of government and values. Russia has lost confidence in international law and cooperation in the international environment because of what they conceive as independent actions of U.S.-led coalitions without United Nations assent. So even if Russia presumably prefers agreements based on common interests with its competitors and claims to adhere to treaties and international bodies[8] – the official documents clearly express that they do not believe that western countries will respect these standards and make fair concessions.

The Russians have experienced that realism is the decisive international model over the last 30 years, where the relative power of the states is what matters. They believe weak states run the risk of forced regime change if they stand up to American pressure. Russian strategic documents state that Western subversion has corrupted the former Soviet republics during Russia’s period of weakness after the Cold War. Some of these have been adopted into NATO and the EU, while the Russian demand for friendly buffer states has been disregarded. Thus, Russian leadership believes it is under attack by the West and wants to look strong to its domestic audience. Their biggest fear is western influence on the younger Russian population, which could potentially spark opposition to the central government. This results in the portrayal of NATO – with its eastwards expansion and global mission sets – as the main threat to Russia and its regional allies. Russia must consequently reestablish a position of strength in order to uphold stability in its proclaimed sphere of exclusive interest.

Recent updates to Russian military and maritime doctrine were published in December 2014 and July 2015. They describe how the use of force in conflicts and international competition is intensified, while international relations are becoming more complicated and unfair.[10] Russia makes it clear that they will protect their vital national interests with all means necessary. The new doctrines reflect the growing global ambition of Russia and particularly in the Arctic – which is its most important region for military purposes and for strengthening its long term economy by exploiting natural resources. The strategic priorities towards 2020 are transforming Russia to a world power, raising the living standards of its people, ensuring economic growth, achieving a balanced multipolar international system through strategic partnerships, and retaining strategic deterrence by modernizing its armed forces.[11]

Russian national identity is complex, but remains more of a European than an Asian one. Ties to Europe have been bolstered by growing economic interdependence in energy trade. Russia made recent investments in renewed and diversified infrastructure to continue exporting energy to the EU into the future. However, conflicts with the West over Syria, Kosovo, NATO-expansion, Ukraine, and the dismissal of former president Medvedev’s proposal to replace NATO with Russian-European security cooperation[12] have led the Russians to look towards other partnerships. The worsening relationship between Russia and western countries coincides with a shifting of the world’s economic center of gravity and future vital markets to Asia. Therefore, Russia is presently engaged in forming strategic partnerships with China, India, and Iran where their shared interests are the suspicion of the West. Such interests include energy supply, mutual understanding of security challenges, and diminishing the role of the U.S. in global order.

The Union State with Belarus is Russia’s most formal alliance. This country is strategically located as a buffer zone to NATO and only 150 miles from the encircled province of Kaliningrad. Then, there is the Collective Security Treaty Organization, which was formed in 1992 in response to NATO. The members are Russia, Belarus, Armenia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan, while Afghanistan and Serbia are observers and Iran is touted as a possible candidate. But the most important in the future, is the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO). This political, economic and military cooperation was formed in 1996 and has seen substantial developments since then. Russia and China have been the most important members since the beginning, with India and Pakistan included in July 2015. Increasing military cooperation on exercises, arms trade, and intelligence has developed over the last years as well as continuing negotiations of a free-trade agreement within the SCO and the Eurasian Economic Union.[14]

The Russian economy is struggling and has been in decline since 2013. Governmental spending was recently slashed by 10% and most sectors had to be reduced, except the defense budget. Reports are suggesting that 60 out of Russia’s 83 different regions are in a state of crisis. The lingering effects of the 2008-09 financial crisis, plummeting oil prices and Western sanctions have been devastating. As a result, the reinstating of the superpower has slowed down and internal unrest is increasing. This is a worrisome development which causes Russia to become less predictable and more aggressive in its foreign relations, especially with its neighbors. Still, Putin’s popularity is at record levels,[16] nationalism is growing stronger, and the people accept the narrative that Russia is the victim of a Western conspiracy. Eventually though, the Russian economy needs to be adequately healthy in order to uphold this loyalty.

Russia and its allies are the world’s leading energy producers, exporting oil, natural gas and uranium on a grand scale. The EU estimates a 27% worldwide increase in energy consumption by 2030,[17] while the U.S. expects a 56% increase by 2040.[18] The export of oil and gas amounted to 70% of Russian foreign sales in 2012 and more than half of total state income.[19] The Russian economy is dependent on energy exports for the foreseeable future and the competition for ownership of natural resources is emphasized in its National Security Strategy. The Russian economy is bound to profit from increasing sales of energy to meet rising Asian need. Oil and gas exports from the Arctic region, Siberia, the Caspian Sea, and Eastern Russia are now targeting this new market. China is itself a world-class energy producer, but has seen substantially growing consumption due to demographics and industrialization. 2007 saw China become a net importer of natural gas and the demand is strong for gas to replace polluting coal power plants. The infrastructure for large gas imports from Russia is now under construction. Sizable gas deals between state owned companies Gazprom and CNBC were completed in November 2014 and May 2015 for at least 68 billion cubic meters per annum. These deals will make China the largest customer of Russian gas for a thirty-year period from 2018 and are valued at $900 billion.[21]

The importance of European trade will eventually become less significant to Russia – even if new infrastructure is still being built for Europe.[22] Eighty percent of Russian energy sales went to the EU as late as 2012, but the EU is diversifying its energy sources and no longer wishes to depend on Russia as the dominant provider.[23] The current dependency denies the EU any significant soft power leverage, and the economic sanctions towards Russia have been painful for the EU as well. The Russians have also shut down the gas flow for political purpose on several occasions.[24] Thus, the EU is looking for other partners to bolster their energy security and Russia responds by looking to alternatives and potentially larger rewards in emerging markets.

Russia will effectively remain the single great power in the Arctic for the near future. Until now, the Russians have been alone in considering the High North as vitally important, but there is growing interest and competitiveness from other major powers and the Arctic nations. Russia is leading the line in an inevitable militarization of the Arctic region while protesting military presence of any other nation in general, and NATO in particular. The establishment of the Russian Arctic Military Command and the Armed Forces modernization program[25] included renewing their strategic submarine fleet, strengthening homeland defense, and building military infrastructure in the Arctic. Their new doctrine emphasize the importance of both nuclear and conventional deterrence, as well as an increased presence of the Northern Fleet in the Arctic and the Atlantic Ocean. An expert group, advising the Norwegian Secretary of Defense, recently published a report describing how these measures are providing better protection for nuclear-armed submarines, as well as the ability to conduct sea-denial and sea-control operations off the coast of Norway.[26]

The Russians would like to retain the upper hand in the High North to avoid interference with their vital military and commercial activity, and to solidify their claims in potential negotiations over international or disputed areas. Also, Russia wants to be in a predisposed position, aimed at calling out a provocative act for an increased Western military presence. Neighboring Norway will remain a representative of the collective western protagonist and will be challenged by Russian activity and its competitive approach in the Arctic region. The geopolitical focus will take priority over regional bilateral relations and cooperation in the Arctic Council.

Norway and the Western Allies

The Norwegian Security Strategy is founded upon the NATO collective defense concept and the national ambition of protecting sovereign rights, dealing with incidents and crises, as well as enabling allied military action on national territory.[27] The absence of any serious threats since the Cold War, combined with the expectancy of proper warning time of an emerging conflict, along with the military supremacy of the NATO alliance, have reduced the national requirements for a significant war prevention capability. The requirements for higher readiness for counterterrorism and contributions to international operations have resulted in more professional forces with quicker reaction time. For this purpose and because of cuts in defense spending the Armed Forces have been transformed from a relatively large and robust mobilization force into a small, balanced and capable readiness force. However, the deteriorating strategic security environment recently led the Norwegian Chief of Defense to advise the Government to increase budgets by $5 billion for the next planning cycle running through 2020. There is a need to bolster territorial defense capability since there are no permanent allied forces stationed in Norway.[28] Failing to do so, he warns, would endanger the ability to sustain a first line of defense long enough to receive allied reinforcements. If Norway has already fallen, NATO would face a tougher task and decision to retake the territory instead of reinforcing it.

The problem, however, is that NATO is not the sustainable and unwavering organization it aims to be. It is becoming increasingly difficult to reach unanimous decisions among member states, which have substantially different security concerns. For example, there is speculation about whether allies are willing to risk a major conflict in the case of any Russian intrusion in the Baltics.[29] Even if Russia’s illegitimate actions in Ukraine sparked a renewed political commitment at the Wales summit to the unity, capability, and relevance of the alliance, the allied nations continue to be unwilling to fund the stated ambitions. The NATO nations committed to invest 2% of their GDP on defense in 2006, but the general will to actually respect the agreement is frail and the alliance is weakening as a consequence. Collective defense spending in NATO has dropped by $76 billion since 2013.[30] Only five out of the 28 nations are spending the required 2% or more in 2015: the U.S., Great Britain, Poland, Greece, and Estonia. Six nations are now shouldering 90% of NATO’s expenses. The American share has grown from about half during the Cold War to 75% currently.[31]

There is a growing frustration in the U.S. with the lack of European will to take responsibility for its own security.[32] The American defense budget is also in decline[33] and the U.S. considers Asia to be its most important future theater.[34] Repeatedly over the years, Washington warned that NATO must avoid becoming irrelevant if the U.S. is going to continue its commitment on the same level.[35] The high-end response capabilities of NATO were gradually reduced over the last 20 years, due to reduced budgets and transformation towards lighter, professional forces of smaller numbers. The military capabilities of the most significant European NATO powers (UK, France, Germany, Spain, and Italy) are now reduced to levels which provide inadequate means to address all the strategic concerns of the alliance.[36] The Norwegian northern flank is thus given a low priority, compared to the eastern and southern regions of NATO. And of course, Russia is more than happy to put pressure on the cohesion of NATO and test its willingness to stand its ground in the periphery towards the Russian borders. Frequent warnings are coming from the Kremlin for NATO to avoid “provocations” in the shape of exercises, shared Ballistic Missile Defense, and allied presence in Eastern-Europe and the Arctic. As a result, Norway must increasingly rely on its National Armed Forces to stand up to Russian aggression before the alliance can mobilize the political will and military strength to respond.

The new American maritime strategy gives guidance for its Navy, Marine Corps, and Coast Guard to increase their presence in the Asia-Pacific region to 60% of deployed ships within 2020, as well as strengthening their numbers in the Middle-East from 30 to 40 ships.[37] Consequently, other regions will be less prioritized even if this depends somewhat on the situation. The White House recently announced an increased budget for the European Reassurance Initiative in 2017,[38] but it is still not enough to reverse the long term trend of reduced U.S. commitment to Europe. The backbone of the maritime commitment to the European theater will be the four BMD-capable destroyers[39] operating from Rota in Spain, rotational deployments of the USMC ARG/MEU, and participation in NATO’s Standing Naval Forces. There is growing attention on the Arctic, but the U.S. is unable to commit necessary resources to increase its activity in the region and finds itself way behind Russia.[41] The American Arctic strategy is thus far reluctant and its presidency of the Arctic Council until 2017 is aimed at promoting peaceful cooperation in the High North. Simultaneously, the Russian military posture in the northern region is now being described as the second Anti-Access/Area Denial (A2AD) challenge, next to the Chinese island disputes. But for the foreseeable future, the U.S. Navy’s activity in the Arctic will primarily revolve around occasional submarine patrols, Coast Guard cutters, and one to two ice-breaking vessels.[42]

Going Forward

Norway is a small state which must adapt to a changing global security environment. It will experience growing political and military pressure from a surge in international activity in the increasingly more important Arctic region. This new attention on the Arctic will result in competition and a more cynical relationship between states, partners, and alliances based on political realism. This changed behavior will challenge regional cooperation and commitment to demilitarization. Russia’s prioritization of the Arctic is currently unprecedented because of the importance of the region for an improved Russian economy and nuclear deterrence. The only superpower in the High North is Russia. The other Arctic NATO-nations are starting to contemplate the increased importance of this region. But there is little effort to converge security strategies apart from agreed adherence to the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf, cooperative environmental protection, and shared climate research.

European NATO nations must increase burden sharing with the U.S. or face diminishing relevance of the transatlantic alliance. Norway will be less reassured by its traditional alliances as the U.S. reduces it European footprint and European unity and prioritization on defense-spending spirals downwards. Even if Norway will always have an asymmetrical relationship to its Russian neighbor, its national defense must be bolstered to uphold a substantial war-preventing threshold and to enable allied reinforcement before it would be too late. Norway must also have a capable military in order to be conceived as a responsible strategic supplier of energy to Europe. The Norwegian Government is obliged to mitigate the weakening of the NATO northern flank by increasing its investment in defense to the agreed 2% level of the GDP. Since 1990, the defense budget dropped from 2.5% of GDP to its current 1.4%, and the armed forces were severely reduced in numbers.[43] The Army shrank from six operational brigades to one in this period, and the reserves were cut by 90%. The Air Force and Navy likewise took big cuts, and there is now debate on the number of new fighter jets, as well as whether to uphold aging capabilities such as maritime patrol aircraft and submarines. Defense experts have been warning about the defense structures balancing on the edge of “critical mass” for the last decade. If Norway remains unwilling to increase its effort to maintain a capable and balanced national defense, it should devote itself increasingly to shared Smart Defense initiatives in order to achieve value for money. This is, however, an increasingly risky strategy when considering the negative trends in the alliance.

Norwegian security policy remains committed to NATO, but contingencies must be developed. In order to uphold commitment from its allies and mitigate the waning focus on the Arctic within NATO, Norway must be a committed member of NATO itself and be seen as willing to take its share of responsibilities and investment. Hosting major NATO events, like the upcoming high visibility exercise in 2018, are wise initiatives that seek to draw attention and resources towards the High North. Further, strengthening bilateral and multilateral partnerships based on long-term shared interests and security concerns within the North Sea region, the European Union, and the United States is of great importance. The U.S. is Norway’s primary ally, and continuing the shared sponsorship of the U.S. Marine Corps Prepositioning Program in Norway is vital. Nordic Defense Cooperation[44] must be developed into full spectrum defense cooperation and Norway should continue to commit forces to the Nordic Battle Group, [45] which is a rotational EU readiness force element. Norway must continue the balanced policy – adopted since long ago – towards Russia. Firm sovereign authority and deterrence through active alliances go hand in hand with acting predictably and avoiding unnecessary provocations on the border. Dialogue and mutual understanding should be nurtured when possible by maintaining active diplomatic relations, seeking cooperation in shared regional interests, and respecting Russian rights to commercial and military activity. However, Russia has chosen to upset the balance by its aggressive behavior and military pressure. Unless Norway and its allies respond by increasing its deterrent capabilities and presence, they signal weakness which invites Russia to adopt an even more dominant posture in the High North.

Conclusion

The Russian-Norwegian relationship is affected by geopolitical developments and crises in other regions, where currently the conflict in Ukraine is reverberating into the Arctic. Norway must consequently respond in a predictable manner in order to regain its balanced approach towards Russia and avoid being a weak link in a strategically vital region. A proper response includes strengthening the Armed Forces, inviting more allied presence on Norwegian territory, and increasing Arctic presence and capabilities. Norway’s best contribution to NATO is to emphasize national defense over foreign deployments, and to raise awareness among its allies of the increasing challenges on the northern flank. Hesitant and overloaded allies and partners must see a committed national effort by Norway before they can be expected to contribute to an increased deterrent posture in Norway and the Arctic.

Commander Daniel Thomassen is a Surface Warfare Officer in the Royal Norwegian Navy. He served as the Commanding Officer of a Fast Patrol Boat from 2005 to 2007. His last assignment was as the Executive Officer of HNoMS Fridtjof Nansen (FFGH) 2012-14. He participated in operations UNIFIL in 2006 and 2007 and RECSYR (Removal of Chemical Weapons from Syria) in 2014. He is currently an International Fellow at the United States Naval War College.

[1] “Northern Sea Route Information Office,” http://www.arctic-lio.com/nsr_ice.

[2] John Greenert, ”The United States Navy Arctic Roadmap for 2014 to 2030,” Chief of Naval Operations, February 2014, 11.

[3] Donald L. Gautier, ”Assessment of Undiscovered Oil and Gas in the Arctic,” Science Vol 324 (2009).

[4] Steve Hargreaves, ”Oil: Only part of the Arctic’s massive resources” , CNN, 19 July 2012.

[5] Martin Katusa, ”The Colder War,” Wiley & Casey Research (2015): 96.

[6] Sarah Wolf, “Svalbard’s Maritime Zones, their Status under International Law and Current and Future Disputes Scenarios, ”Working Paper FG 2, 2013/Nr. 02, January 2013, 37.

[7] See Vladimir Putin, “Address by President of the Russian Federation,” March 18, 2014, http://en.kremlin.ru/events/president/news/20603. (NATO’s intervention in Kosovo 1999 and the second Iraq-war 2003 are considered illegitimate by the Russians and were used by Putin as examples of western double standards when annexing Crimea.)

[8] President of the Russian Federation, “The Military Doctrine of the Russian Federation,” December 2014.

[9] U.S. House Armed Services Committee: “Understanding and Deterring Russia: U.S. Policies and Strategies,” February 2016, https://youtu.be/Th9vNtNReMw.

[10] President of the Russian Federation, “The Military Doctrine of the Russian Federation,” December 2014.

[11] President of the Russian Federation, ”National Security Strategy of the Russian Federation to 2020,” May 2009.

[12] Radio Free Europe Radio Liberty, ”Russia Unveils Proposal For European Security Treaty,” November 2009.

[13] See “China hosts largest ever military drill with Russia, other SCO nations,” August 2014, https://www.rt.com/news/182400-sco-military-drills-china.

[14] Daria Chernyshova, “India must speed up talks on free trade zone with Eurasian Economic Union,” Sputnik International: (2015).

[15] Stratfor Global Intelligence, “Conversation: Russia’s Perfect Economic Storm,” August 2015, https://www.stratfor.com/.

[16] Alberto Nardelli, Jennifer Rankin and George Arnett, “Vladimir Putin’s approval rating at record levels,” The Guardian, July 2015.

[17] European Commission, “European Energy Security Strategy,” May 2015.

[18] Ray Maybus, “A Cooperative Strategy for 21st Century Seapower,” Department of the Navy, March 2015, 60.

[19] Alan Neuhauser, and Paul D. Shinkman, “Europe, Russia Ensnared in ‘Energy Cold War,’ Experts Say,” U.S. News, April 2014.

[20] U.S. Energy Information, “International Energy Statistics” http://www.eia.gov/.

[21] Kenneth Rapoza, Russian Government Ratifies Huge China Gas Pipeline Deal”, Forbes, May 2015.

[22] See Stephen F. Szabo, “Germany, Russia, and the rise of Geo-Economics,” Bloomsbury, 2015. The oil terminal Ust-Luga in the Baltics, as well as gas pipelines North-Stream (Baltic Sea) and South Stream (Black Sea).

[23] See European Commission, “European Energy Security Strategy,” May 2015. (The Russian market share of EU gas was 39% in 2013. The Norwegian was 20%.)

[24] Adam Withnall, “Putin’s gas threat: What happens if Russia cuts the gas to Europe?,” The Independent, February 2015.

[25] See Expert Commission on Norwegian Security and Defense Policy, ”Unified Effort,” Norwegian Ministry of Defense, 2015, 18-19. (The ”GPV-2020” program is spending $3500 billion to modernize the Russian Armed Forces and strengthen the Military-Industrial Complex.)

[26] Expert Commission on Norwegian Security and Defense Policy, ”Unified Effort,” Norwegian Ministry of Defense, 2015, 20.

[27] Defense Long Term Proposition (2013-2016) ver 13.0, “Et Forsvar for Vår Tid,” Norwegian Ministry of Defense, December 2014, 25-27.

[28] Haakon Bruun-Hansen, “Norwegian Armed Forces in Transition: Strategic Defence Review by the Norwegian Chief of Defence,” Norwegian Armed Forces, 2015.

[29] Jarno Limnell, ”Will NATO Protect All Members Equally?,” Breaking Defense, September 2014.

[30] Kedar Pavgi, ”NATO Members’ Defense Spending, in Two Charts,” Defense One, June 2015.

[31] Jorge Benitez, ”Will the U.S.‘Rebalance’ Its Contribution to NATO?” Defense One, October 2013.

[32] BBC, “US diplomat warns Europe of dangerous defence spending cuts,” March 2015.

[33] Andrew Tilghman, “Lawmakers: Sequestration is here to stay,” Military Times, March 2015.

[34] Robert Burns, “Ash Carter says U.S. is opening new phase of Asia pivot,” Associated Press, April, 2015.

[35] Ted G. Carpenter, “NATO, European Spending and US Grievances,” CATO Institute, May 2015.

[36] Gary J. Schmitt, “A Hard Look At Hard Power: Assessing the Defense Capabilities of Key U.S. Allies and Security Partners,” Strategic Studies Institute and Army War College Press, July 2015, ch. 4, 10, 15.

[37] Ray Maybus, “A Cooperative Strategy for 21st Century Seapower,” Secretary of the Navy, March 2015, 11.

[38] White House Press Release, “FACT SHEET: The FY2017 European Reassurance Initiative Budget Request,” Office of the Press Secretary, February 2016.

[39] Arleigh Burke-class destroyers deployed for Ballistic Missile Defense.

[40] US Marine Corps Amphibious Readiness Group/Marine Expeditionary Unit: See http://www.marines.mil/Portals/59/Amphibious%20Ready%20Group%20And%20Marine%20Expeditionary%20Unit%20Overview.pdf.

[41] Steven L. Myers, “U.S. Is Playing Catch-Up With Russia in Scramble for the Arctic,” New York Times, August 2015.

[42] Joseph R. Fonseca, ”Seawolf Completes Arctic Deployment,” Marinelink.com: (2015).

[43] Diesen og Narum, “Norsk forsvarsevne – en varslet avvikling,” Aftenposten, May 2015.

[44] NORDEFCO, http://www.nordefco.org/the-basics-about-nordefco.

[45] Elizabeth Braw, “The Nordic Battlegroup, Ready and Willing,” World Affairs: (2015).