The following testimony published on Information Dissemination, and is shared with the author’s permission.

By Jon Solomon

Testimony before the House Armed Services Committee

Subcommittee on Seapower and Projection Forces

Prepared Statement of Jonathan F. Solomon

Senior Systems and Technology Analyst, Systems Planning and Analysis, Inc.

December 9th, 2015

The views expressed herein are solely those of the author and are presented in his personal capacity on his own initiative. They do not reflect the official positions of Systems Planning and Analysis, Inc. and to the author’s knowledge do not reflect the policies or positions of the U.S. Department of Defense, any U.S. armed service, or any other U.S. Government agency. These views have not been coordinated with, and are not offered in the interest of, Systems Planning and Analysis, Inc. or any of its customers.

Thank you Chairman Forbes and Ranking Member Courtney and all the members of the Seapower and Projection Forces subcommittee for granting me the honor of testifying today and to submit this written statement for the record.

I am a former U.S. Navy Surface Warfare Officer (SWO), and served two Division Officer tours in destroyers while on active duty from 2000-2004. My two billets were perhaps the most tactically-intensive ones available to a junior SWO: Anti-Submarine Warfare Officer and AEGIS Fire Control Officer. As the young officer responsible for overseeing the maintenance and operation of my destroyers’ principal combat systems, I obtained an unparalleled foundational education in the tactics and technologies of modern naval warfare. In particular, I gained a fine appreciation for the difficulties of interpreting and then optimally acting upon the dynamic and often ambiguous “situational pictures” that were produced by the sensors I “owned.” I can attest to the fact that Clausewitz’s concepts of “fog” and “friction” remain alive and well in the 21st Century in spite of, and sometimes exacerbated by, our technological advancements.

My civilian job of the past eleven years at Systems Planning and Analysis, Inc. has been to provide programmatic and systems engineering support to various surface combat system acquisition programs within the portfolio of the Navy’s Program Executive Officer for Integrated Warfare Systems (PEO IWS). This work has provided me an opportunity to participate, however peripherally, in the development of some of the surface Navy’s future combat systems technologies. It has also enriched my understanding of the technical principles and considerations that affect combat systems performance; this is no small thing considering that I am not an engineer by education.

In recent years, and with the generous support and encouragement of Mr. Bryan McGrath, I’ve taken up a hobby of writing articles that connect my academic background in maritime strategy, naval history, naval technology, and deterrence theory with my professional experiences. One of my favorite topics concerns the challenges and opportunities surrounding the potential uses of electronic warfare in modern maritime operations. It’s a subject that I first encountered while on active duty, and later explored in great detail during my Masters thesis investigation of how advanced wide-area oceanic surveillance-reconnaissance-targeting systems were countered during the Cold War, and might be countered in the future.

Electronic warfare receives remarkably little attention in the ongoing debates over future operating concepts and the like. Granted, classification serves as a barrier with respect to specific capabilities and systems. But electronic warfare’s basic technical principles and effects are and have always been unclassified. I believe that much of the present unfamiliarity concerning electronic warfare stems from the fact that it’s been almost a quarter century since U.S. naval forces last had to be prepared to operate under conditions in which victory—not to mention survival—in battle hinged upon achieving temporary localized mastery of the electromagnetic spectrum over the adversary.

America’s chief strategic competitors intimately understand the importance of electronic warfare to fighting at sea. Soviet Cold War-era tactics for anti-ship attacks heavily leveraged what they termed “radio-electronic combat,” and there’s plenty of open source evidence available to suggest that this remains true in today’s Russian military as well.[i] The Chinese are no different with respect to how they conceive of fighting under “informatized conditions.”[ii] In a conflict against either of these two great powers, U.S. maritime forces’ sensors and communications pathways would assuredly be subjected to intense disruption, denial, and deception via jamming or other related tactics. Likewise, ill-disciplined electromagnetic transmissions by U.S. maritime forces in a combat zone might very well prove suicidal in that they could provide an adversary a bullseye for aiming its long-range weapons.

To their credit, the Navy’s seniormost leadership have gone to great lengths to stress the importance of electronic warfare in recent years, most notably in the new Maritime Strategy. They have even launched a new concept they call electromagnetic maneuver warfare, which appears geared towards exactly the kinds of capabilities I am about to outline. It is therefore quite likely that major elements of the U.S. Navy’s future surface warfare vision, Distributed Lethality, will take electronic warfare considerations into account. I would suggest that Distributed Lethality’s developers do so in three areas in particular: Command and Control (C2) doctrine, force-wide communications methods, and over-the-horizon targeting and counter-targeting measures.

First and foremost, Distributed Lethality’s C2 approach absolutely must be rooted in the doctrinal philosophy of “mission command.” Such doctrine entails a higher-echelon commander, whether he or she is the commander of a large maritime battleforce or the commander of a Surface Action Group (SAG) consisting of just a few warships, providing subordinate ship or group commanders with an outline of his or her intentions for how a mission is to be executed, then delegating extensive tactical decision-making authority to them to get the job done. This would be very different than the Navy’s C2 culture of the past few decades in which higher-echelon commanders often strove to use a “common tactical picture” to exercise direct real-time control, sometimes from a considerable distance, over subordinate groups and ships. Such direct control will not be possible in contested areas in which communications using the electromagnetic spectrum are—unless concealed using some means—readily exploitable by an electronic warfare-savvy adversary. Perhaps the adversary might use noise or deceptive jamming, deceptive emissions, or decoy forces to confuse or manipulate the “common picture.” Or perhaps the adversary might attack the communications pathways directly with the aim of severing the voice and data connections between commanders and subordinates. An adept adversary might even use a unit or flagship’s insufficiently concealed radio frequency emissions to vector attacks. It should be clear, then, that the embrace of mission command doctrine by the Navy’s senior-most leadership on down to the deckplate level will be critical to U.S. Navy surface forces’ operational effectiveness if not survival in future high-end naval combat.

Let me now address the question of why a surface force must be able to retain some degree of voice and data communications even when operating deep within a contested zone. As I alluded earlier, I consider it highly counterproductive if not outright dangerous for a higher-echelon commander to attempt to exercise direct tactical control over subordinate assets in the field under opposed electromagnetic conditions. But that doesn’t mean that the subordinate assets should not share their sensor pictures with each other, or that those assets should not be able to spontaneously collaborate with each other as a battle unfolds, or that higher-echelon commanders should not be able to issue mission intentions and operational or tactical situation updates—or even exercise a veto over subordinates’ tactical decisions in extreme cases. A ship or an aircraft can, after all, only “see” on its own what is within the line of sight of its onboard sensors. If one ship or aircraft within some group detects a target of opportunity or an inbound threat, that information cannot be exploited to its fullest if the ship or aircraft in contact cannot pass what it knows to its partners in a timely manner with requisite details. In an age where large salvos of anti-ship missiles can cover hundreds—and in a few cases thousands—of miles in the tens of minutes, where actionable detections of “archers” and “arrows” can be extremely fleeting, and where only minutes may separate the moments in which each side first detects the other, the side that can best build and then act upon a tactical picture is, per legendary naval tactical theorist Wayne Hughes, the one most likely to fire first effectively and thus prevail.[iii]

This requires the use of varying forms of voice and data networking as tailored to specific tactical or operational C2purposes. A real-time tactical picture is often needed for coordinating defenses against an enemy attack. A very close to real-time tactical picture may be sufficient for coordinating attacks against adversary forces. Non-real time communications may be entirely adequate for a higher-echelon commander to convey mission guidance to subordinates.

But how to conceal these communications, or at least drastically lower the risk that they might be intercepted and exploited by an adversary? The most secure form of communications against electronic warfare is obviously human courier, and while this was used by the U.S. Navy on a number of occasions during the Cold War to promote security in the dissemination of multi-day operational and tactical plans, it is simply not practicable in the heat of an ongoing tactical engagement. Visible-band and infrared pathways present other options, as demonstrated by the varying forms of “flashing light” communications practiced over the centuries. For instance, a 21st Century flashing light that is based upon laser technologies would have the added advantage of being highly directional, as its power would be concentrated in a very narrow beam that an adversary would have to be very lucky to be in the right place at the right time to intercept. That said, visible-band and infrared systems’ effective ranges are fairly limited to begin with when used directly between ships, and even more so in inclement weather. This may be fine if a tactical situation allows for a SAG’s units to be operating in close proximity. However, if unit dispersal will often be the rule in contested zones in order to reduce the risk that an adversary’s discovery of one U.S. warship quickly results in detection of the rest of the SAG, then visible-band and infrared pathways can only offer partial solutions. A broader portfolio of communications options is consequently necessary.

It is commonly believed that the execution of strict Emissions Control (EMCON) in a combat zone in order to avoid detection (or pathway exploitation) by an adversary means that U.S. Navy warships would not be able to use any form of radiofrequency communications. This is not the case. Lower-frequency radios such as those that operate in the (awkwardly titled) High, Very High, and Ultra High Frequency (HF, VHF, and UHF) bands are very vulnerable because their transmission beams tend to be very wide. The wider a transmission beam, the greater the volume through which the beam will propagate, and in turn the greater the opportunity for an adversary’s signals intelligence collectors to be in the right place at the right time. In order to make lower-frequency radio communications highly-directional and thereby difficult for an adversary to intercept, a ship’s transmitting antennas would have to be far larger than is practical. At the Super High Frequency (SHF) band and above, though, transmission beamwidth using a practically-sized antenna becomes increasingly narrow and thus more difficult to intercept. This is why the Cold War-era U.S. Navy designed its Hawklink line-of-sight datalink connecting surface combatants and the SH-60B helicopter to use SHF; the latter could continually provide sonarbuoy, radar, or electronic support measures data to the former—and thereby serve as an anti-submarine “pouncer” or an anti-ship scout—with a relatively low risk of the signals being detected or exploited. In theory, the surface Navy might develop a portfolio of highly-directional line-of-sight communications systems that operate at SHF or Extremely High Frequency (EHF)/Millimeter-wave (MMW) bands in order to retain an all-weather voice and data communications capability even during strict EMCON. The Navy might also develop high-band communications packages that could be carried by manned or unmanned aircraft, and especially those that could be embarked aboard surface combatants, so that surface units could communicate securely over long-distances via these “middlemen.” Shipboard and airframe “real estate” for antennas is generally quite limited, though, so the tradeoff for establishing highly-directional communications may well be reduced overall communications “bandwidth” compared to what is possible when also using available communications systems that aren’t as directional. Nevertheless, this could be quite practicable in a doctrinal culture that embraces mission command and the spontaneous local tactical collaboration of ships and aircraft in a SAG.

High-directionality also means that a single antenna can only communicate with one other ship or aircraft at a time—and it must know where that partner is so that it can point its beam precisely. If a transmission is meant for receipt by other ships or aircraft, it must either be relayed via one or more “middleman” assets’ directional links to those units or it must be broadcast to them using less-directional pathways. Broadcast is perfectly acceptable as a one-way transmissions method if the broadcaster is either located in a relatively secure and defensible area or alternatively is relatively expendable. An example of the former might be an airborne early warning aircraft protected by fighters or surface combatants broadcasting its radar picture to friendly forces (and performing as a local C2 post as well) using less-directional lower-frequency communications. An example of the latter might be Unmanned Aerial Systems (UAS) launchable by SAG ships to serve as communications broadcast nodes; a ship could uplink to the UAS using a highly-directional pathway and the UAS could then rebroadcast the data within a localized footprint. Higher-echelon commanders located in a battlespace’s rearward areas might also use broadcast to provide selected theater- and national-level sensor data, updated mission guidance, or other updated situational information to forward SAGs. By not responding to the broadcast, or by only responding to it via highly-directional pathways, receiving units in SAGs would gain important situational information while denying the adversary an easy means of locating them.

Low Probability of Intercept (LPI) radiofrequency communications techniques provide surface forces an additional tool that can be used at any frequency band, directional or not. By disguising waveforms to appear to be ambient radiofrequency noise or by using reduced transmission power levels and durations, an adversary’s signals intelligence apparatus might not be able to detect an LPI transmission even if it is positioned to do so. I would caution, though, that any given LPI “trick” might not have much operational longetivity. Signal processing technologies available on the global market may well reach a point, if they haven’t already, where a “trick” works only a handful of times—or maybe just once—and thereafter is recognized by an adversary. Many LPI techniques accordingly should be husbanded for use only when necessary in a crisis or wartime, and there should be a large enough “arsenal” of them to enable protracted campaigning.

Finally, I want to briefly discuss the importance of providing our surface force with an actionable over-the-horizon targeting picture while denying the same to adversaries. The U.S. Navy is clearly at a deficit relative to its competitors regarding anti-ship missile range. This is thankfully changing regardless of whether we’re talking about the Long-Range Anti-Ship Missile (LRASM), a Tomahawk-derived system, or other possible solutions.

It should be noted, though, that a weapon’s range on its own is not a sufficient measure of its utility. This is especially important when comparing our arsenal to those possessed by potential adversaries. A weapon cannot be evaluated outside the context of the surveillance and reconnaissance apparatus that supports its employment.

In one of my earlier published works, I set up the following example regarding effective first strike/salvo range at the opening of a conflict:

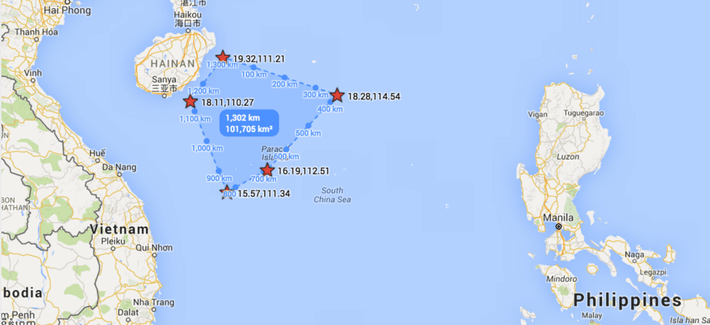

Optimal first-strike range is not necessarily the same as the maximum physical reach of the longest-ranged weapon system effective against a given target type (i.e., the combined range of the firing platform and the weapon it carries). Rather, it is defined by trade-offs in surveillance and reconnaissance effectiveness…This means that a potential adversary with a weapon system that can reach distance D from the homeland’s border but can achieve timely and high-confidence peacetime cueing or targeting only within a radius of 0.75D has an optimal first-strike range of 0.75D…This does not reduce the dangers faced by the defender at distance D but does offer more flexibility in using force-level doctrine, posture, plans, and capabilities to manage risks.[iv]

Effective striking range is reduced further once a war breaks out and the belligerents take off their gloves with respect to each others’ surveillance and reconnaissance systems. The qualities and quantities of a force’s sensors, and the architecture and counter-detectability of the data pathways the force uses to relay its sensors’ “pictures” to “consumers” matter just as much as the range of the force’s weapons.[v] Under intense electronic warfare opposition, they arguably matter even more.

For a “shooter” to optimally employ long-range anti-ship weaponry, it must know with an acceptable degree of confidence that it is shooting at a valid and desirable target. Advanced weapons inventories, after all, are finite. It can take considerable time for a warship to travel from a combat zone to a rearward area where it can rearm; this adds considerable complexities to a SAG maintaining a high combat operational tempo. Nor are many advanced weapons quickly producible, and in fact it is far from clear that the stockpiles of some of these weapons could be replenished within the timespan of anything other than a protracted war. This places a heavy premium on not wasting scarce weapons against low-value targets or empty waterspace. As a result, in most cases over-the-horizon targeting requires more than just the detection of some contact out at sea using long-range radar, sonar, or signals collection and direction-finding systems. It requires being able to classify the contact with some confidence: for example, whether it is a commercial tanker or an aircraft carrier, a fishing boat or a frigate, a destroyer or a decoy. An electronic warfare-savvy defender can do much to make an attacker’s job of contact classification extraordinarily difficult in the absence of visual-range confirmation of what the longer-range sensors are “seeing.”

A U.S. Navy SAG would therefore benefit greatly from being able to embark or otherwise access low observable unmanned systems that can serve as over-the-horizon scouts. These scouts could be used not only for reconnaissance, but also for contact confirmation. They could report their findings back to a SAG via the highly-directional pathways I discussed earlier, perhaps via “middlemen” if needed.

Likewise, a U.S. Navy SAG would need to be able to degrade or deceive an adversary’s surveillance and reconnaissance efforts. There are plenty of non-technological options: speed and maneuver, clever use of weather for concealment, dispersal, and deceptive feints or demonstrations by other forces that distract from a “main effort” SAG’s thrust. Technological options employed by a SAG might include EMCON and deceptive emissions against the adversary’s signals intelligence collectors, and noise or deceptive jamming against the adversary’s active sensors. During the Cold War, the U.S. Navy developed some very advanced (and anecdotally effective) shipboard deception systems to fulfill these tasks against Soviet sensors. Unmanned systems might be particularly attractive candidates for performing offboard deception tasks and for parrying an adversary’s own scouts as well.

If deception is to be successful, a SAG must possess a high-confidence understanding of—and be able to exercise agile control over—its emissions. It must also possess a comprehensive picture of the ambient electromagnetic environment in its area of operations, partly so that it can blend in as best as possible, and partly to uncover the adversary’s own transient LPI emissions. This will place a premium on being able to network and fuse inputs from widely-dispersed shipboard and offboard signals collection sensors. Some of these sensors will be “organic” to a SAG, and some may need to be “inorganically” provided by other Navy, Joint, or Allied forces. Some will be manned, and other will likely be unmanned. This will also place a premium on developing advanced signal processing and emissions correlation capabilities.

We can begin to see, then, the kinds of operational and tactical possibilities such capabilities and competencies might provide U.S. Navy SAGs. A SAG might employ various deception and concealment measures to penetrate into the outer or middle sections of a hotly contested zone, perform some operational task(s) of up to several days duration, and then retire. Other naval or Joint forces might be further used to conduct deception and concealment actions that distract the adversary’s surveillance-reconnaissance resources (and maybe decision-makers’ attentions) from the area in which the SAG is operating, or perhaps from the SAG’s actions themselves, during key periods. And still other naval, Joint, and Allied forces might conduct a wide-ranging campaign of physical and electromagnetic attacks to temporarily disrupt if not permanently roll back the adversary’s surveillance-reconnaissance apparatus. Such efforts hold the potential of enticing an adversary to waste difficult-to-replace advanced weapons against “phantoms,” or perhaps distracting or confusing him to such an extent that he attacks ineffectively or not at all.

The tools and tactics I’ve outlined most definitely will not serve as “silver bullets” that shield our forces from painful losses. And there will always be some degree of risk and uncertainty involved in the use of these measures; it will be up to our force commanders to decide when conditions seem right for their use in support of a particular thrust. These measures should consequently be viewed as force-multipliers that grant us much better odds of perforating an adversary’s oceanic surveillance and reconnaissance systems temporarily and locally if used smartly, and thus better odds of operational and strategic successes.

With that, I look forward to your questions and the discussion that will follow. Thank you.

Jon Solomon is a Senior Systems and Technology Analyst at Systems Planning and Analysis, Inc. in Alexandria, VA. He can be reached at jfsolo107@gmail.com. The views expressed herein are solely those of the author and are presented in his personal capacity on his own initiative. They do not reflect the official positions of Systems Planning and Analysis, Inc. and to the author’s knowledge do not reflect the policies or positions of the U.S. Department of Defense, any U.S. armed service, or any other U.S. Government agency. These views have not been coordinated with, and are not offered in the interest of, Systems Planning and Analysis, Inc. or any of its customers.

[i] For example, see the sources referenced in my post “Advanced Russian Electronic Warfare Capabilities.” Information Dissemination blog, 16 September 2015,http://www.informationdissemination.net/2015/09/advanced-russian-electronic-warfare.html

[ii] For examples, see 1. John Costello. “Chinese Views on the Information “Center of Gravity”: Space, Cyber and Electronic Warfare.” Jamestown Foundation China Brief, Vol. 15, No. 8, 16 April 2015,http://www.jamestown.org/programs/chinabrief/single/?tx_ttnews%5Btt_news%5D=43796&cHash=c0f286b0d4f15adfcf9817a93ae46363#.Vl4aL00o7cs; 2. “Annual Report to Congress: Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China 2015.” (Washington, DC: Office of the Secretary of Defense, 07 April 2015), 33, 38.

[iii] CAPT Wayne P. Hughes Jr, USN (Ret). Fleet Tactics and Coastal Combat, 2nd ed. (Annapolis, MD: U.S. Naval Institute Press, 2000), 40-44.

[iv] Jonathan F. Solomon. “Maritime Deception and Concealment: Concepts for Defeating Wide-Area Oceanic Surveillance-Reconnaissance-Strike Networks.” Naval War College Review 66, No. 4 (Autumn 2013): 113-114.

[v] See my posts 1. “21st Century Maritime Operations Under Cyber-Electromagnetic Opposition, Part II.” Information Dissemination blog, 22 October 2014, http://www.informationdissemination.net/2014/10/21st-century-maritime-operations-under_22.html; and 2. “21st Century Maritime Operations Under Cyber-Electromagnetic Opposition, Part III.” Information Dissemination blog, 23 October 2014,http://www.informationdissemination.net/2014/10/21st-century-maritime-operations-under_23.html

Featured Image: Persian Gulf (Feb. 5, 2007) – Air Traffic Controller 1st Class Otto Delacruz identifies an air contact to Air Traffic Controller 1st Class Brent Watson standing watch in the ship’s helicopter direction center aboard USS Boxer (LHD 4). (U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist Seaman Joshua Valcarcel)