The following is a two-part series on the role cruisers played in the Soviet and Russian Navy. The first part examined historical inspiration for developing a cruiser-focused force, concepts of employment, and strategic rationale. Part II will focus on how cruisers shaped the environment through forward presence during the Cold War, and how the nature of presence may evolve into the future.

By Alek Clarke

The Multi-Layered Approach of Presence

“Naval losses are hard to make good. Therefore, each defeat inflicted on an enemy means not only the achievement of the goal of the given combat clash but the creation of favorable conditions for quite a long time for solving the next task.” Admiral Sergey Gorshkov1

It was not of course all about the cruisers. Even with two ‘levels’ of construction the Soviets would not have been able to devote enough resources to the construction of cruisers to sustain the number of hulls required to maintain the level of visibility that is a requisite of presence. In simple terms they hit the same problem the Royal Navy (RN) of the 1920s faced. The pre-WWI Fisher reforms sold off all the old ships which had been used as presence vessels2 – in the phraseology of that period, gunboats,3 so what to build as new build vessel for presence?

The RN in the 1920s focused on light cruisers, ships of 6,000 tons and a main armament of six to eight six-inch guns.4 Yet, still even in that period when defense budgets were able to call on far larger proportions of national funds than they can today, the RN was not able to acquire enough (even discounting the artificial strictures imposed by the arms limitations treaties5) to maintain the visibility portion of presence with only these ships. The Soviet solution to this problem was not that different to Britain’s in the 1920s; to focus efforts on the more useful ships where they could be of most benefit, and to make use of other ships to achieve the visibility aspect of the presence mission elsewhere.6

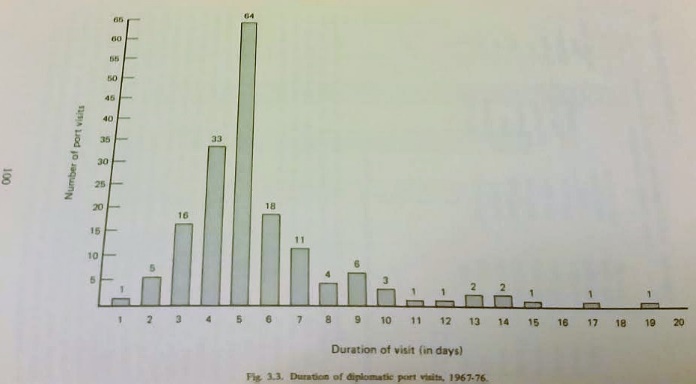

This visibility mission, often characterized as ‘Showing the Flag,’7 really started again for the Soviet Union after a 14-year hiatus that included the WWII years with a visit by a Sverdlov-class cruiser to Britain to take part in Queen Elizabeth’s 1953 Coronation Review.8 This visit was the harbinger of a busy future, and four years later another Sverdlov-class vessel, accompanied this time by a destroyer, made the first visit by a Soviet Union vessel to Latakia, Syria;9 a naval relationship which has continued to have an impact on world events to this day. The growing use of naval diplomacy by the Soviet Union in the early to mid-Cold War era is highlighted by the numerical increase in port visits: over a fourteen year period (1953-66) 37 port visits were made, 21 of which were to developed countries, yet over the next ten year period (1967-76) 170 port visits were made, of which only 30 were to developed countries,10 and 108 or 77.6 percent of which involved two or more vessels.11

What reveals more is the theater the visits were focused on: 69 went to the Indian Ocean –the highest number. Of these visits though, 29 took place during a two-year period, 1968-9, while the Soviet Navy was settling on which Indian Ocean ports to use as either a primary or secondary operational hub to support the Indian Ocean Squadron (the second forward deployed squadron the Soviet Union created), in the region.12 These visits were arguably more about testing the port facilities of allies, although they were also important for presence. In the retreating colonial atmosphere where the traditional power, Britain, was withdrawing and the new powers, America and the Soviet Union, were still integrating themselves – these visits served to foster relationships and grow connections.

The second largest was the Atlantic, followed by the Mediterranean (which was the home of the first Soviet Union forward deployed squadron), and then the Pacific.13 The visits were very much focused at the ‘southern flank,’ and nations which belonged to NATO. They served to highlight the reach and capability of the Soviet Union to these nations in a very visible and of course ‘peaceful’ way.

Alongside the visibility of presence gained from port visits, these visits also provided the opportunity to build relationships and gather human as well as electronic intelligence. Whilst of course this is true of both the visitor and host, the initiation of the visit by the visitor, and rules of diplomatic etiquette (if followed by both sides), will usually serve to give the visitor an edge. This can be crucial in providing knowledge to the capability and capacity (i.e. how many ships/units can be actually made available at any time for operations) of potential opponents and allies.

Electronic intelligence and human intelligence are factors which are widely discussed,15 but still need to be highlighted. Even a ship outfitted with a moderately capable Command, Control, and Communication (C3) setup can provide significant listening capability whilst just passing through an ocean. Many nations put in far more basic equipment. This variance in electronic equipment outfit can often be a significant explanation as to the cost differences between procurements of similar vessels for different countries.

These passive sensors are nothing though compared to the turning on of more active sensor systems as both capability sets provide governments with the ability of proactively observing events within an area so that they have as much and as accurate information as possible. This capacity, when combined with the relationships that are built by ongoing diplomatic and military interaction, can provide interested nations with the ability to more accurately predict the possibility, as well as take advantage, of events or opportunities.

The Soviets at many times, but most notably in the 1975 Angolan Crisis,16 were able to build upon forces already in the area, use local knowledge, as well as on-the-spot presence to react to events. The reinforcements were carefully managed to present a deterrent to the threatened increased American involvement – which never actually materialized. Although there existed the presence of two carrier battle groups, based around the USS John F. Kennedy and the USS Saratoga in the Gibraltar/Atlantic area at the time, such involvement was a significant possibility.17

The presence of the ships combined with the airlift of mainly Cuban military personnel and Soviet equipment for which those ships provided cover secured the installation of the Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA) in power, rather than the American- or Chinese-backed organisations.18 While the warships never directly took part in combat operations, their presence allowed the Soviets to keep a very close eye on the situation.

This success is the capability which presence is an auger for. The vessel that is seen serves as a symbol and warning for all the force that might be dispatched. While there, the ships can provide more tangible benefits in terms of gathering intelligence and building relationships which could make a larger deployment unnecessary. If such larger deployments do become necessary, the information already gathered enables governments to refine and focus any such deployment to achieve the aims they desire more effectively and efficiently.

These successes were ultimately why the Soviet Navy eventually chose to procure aircraft carriers, as well as cruisers.19 It was not the pursuit of German-style ‘Risk Fleet’ strategy,20 but a realization that adding another level of presence would give them more diplomatic and operational flexibility. With the addition of aircraft carriers to its cruiser force the Soviet government was able to maintain ongoing presence within regions and raise the level of commitment if warranted, but always building upon the foundation of presence that was the ongoing feature of their policy. It was their ability to magnify the presence of Soviet forces by the addition of an organic sea-based fixed-wing component (giving the options for overflight, like the British achieved in Belize/British Honduras vs Guatemala with the Ark Royal in 197221) that was their peacetime selling point.

Future Possibilities

“The best lack all conviction, while the worst are full of passionate intensity.”-W.B. Yeats, The Second Coming. 23

The primary question that will undoubtedly feature in future presence discussions is whether manned or unmanned systems are better value for money. Whilst those who are budget-minded will no doubt seek to replace manned with the unmanned, in reality the more sensible idea would be to consider the lessons of the past, and perhaps even the principle foundation of presence itself. It is a standard of presence that the small vessel that is seen is an active emblem for the far larger fleet that can be sent. This idea has been built upon. Helicopters have been used along with a detachment of marines/infantry to give an impression that a far larger ground force was available – as well as demonstrating their ability to appear anywhere. From all of this, there is therefore a successful precedent, whereby smaller/lower presence units are used to magnify the presence/area of effect of a higher impact unit. This is most likely to be the best option for unmanned systems, that they be part of a larger manned system or work in tandem with one so that the human side of presence is involved, while the unmanned aerial and surface systems would serve to magnify its impact.

It is as such a probability that the utility of small vessels for presence effect missions will grow; yet they will always depend, as the Russians and Soviets demonstrated, upon the strength of will encapsulated in their orders, the quality of their crew, and the foundation provided by the capable vessels they represent. This could be a basis for the promulgation of a two tier naval force, one with a strong core of warfighting vessels (aircraft carriers, destroyers, amphibious ships and submarines) kept at a high level of training and readiness, but which are deployed rarely – except to the most dangerous areas that require something more.

The second tier would be a larger number of presence/flotilla vessels, which would be almost continually forward deployed to show the flag, provide maritime security, and demonstrate interest around the world.24 Such an idea is not new:25 in fact it was the foundation of Soviet naval diplomacy and of the British Empire’s maritime policy for most of the 19th, and early 20th centuries. However, in an age where the complexity and advanced technology of weapons systems (and warships in particular) seems to be a major selling point for their procurement, such a premise may be difficult to sell.

Many countries possess both a Coast Guard and a Navy, and in the case of the U.S., the size, level of armament, and general sophistication of the Coast Guard cutters means that they are in many ways just as useful as USN ships in providing presence. This is not the case with most nations, but Britain as a nation which has a longstanding maritime history is an example of this.

In fact, Britain possesses not only a Coast Guard, but also a Border Force; both of which operate ships. Although the vessels are capable in localized maritime constabulary roles (and two of the Border Force vessels were deployed with HMS Bulwark to help with the 2015 Mediterranean Crisis26) – they are not as capable in the presence role as the River-class OPVs or minesweepers the RN currently uses for its small ship missions.

This does not mean though these Coast Guard and Border Force ships are not useful, just that they cannot be considered interchangeable with the RN ships. The British Government, which is currently procuring three more River-class vessels27 and has made an announcement to procure two further vessels, might wish to look again at the this very useful and adaptable class and see what more can be achieved from its design or could be gained by further increasing numbers in a presence context.

Conclusion

Presence matters. Events are decided by those who care enough to show up28 – not by those who sit back on the sidelines. The Soviet Navy, and to a large extent the modern Russian Navy, was not built on its wartime missions; but rather its peacetime roles – in contrast to Western navies that have prioritized warfighting constructs.

This focus is understandable when considering the constricting budgets these navies face and requirements that war would undoubtedly place on them. However, while the last year that British forces were not in action was 1968, wars which require naval forces to do more than support land forces are not that common – in fact the 1982 Falklands War was it for Britain. This does not mean the capabilities are not needed, as when they are needed they are really needed; but it does mean that in order to justify themselves navies need to be more engaged with peacetime possibilities and roles. They need to be engaged with the full role of the cruiser, the peacetime ambassador and bobby on the beat, and the warrior.

Lack of focus on peacetime roles weakens navies in the political sense, as in a democracy the leaders respond to the public and media, who in turn largely respond to what is most visible, most immediate – not having the time to really consider the long term before the next thing comes along. This weakness was of course less of a problem for the Soviet Navy, and to an extent the Russian Navy, which has to impress a small number of stakeholders. Western navies however need to be in the public debate in order to justify the expense, whether it is for warfighting or for peacetime.

This is not because democratic governments do not care about defense, but because the nature of democracy means that that the more visible the department of government, the more it shows its relevance to the public and the harder it is to cut. The Soviet Navy (admittedly working in a less democratic national governance model) managed to build a fleet for war by mastering and building recognition from the missions of peacetime.

This is not to say that western navies need to build flotilla vessels, although they could be useful as presence and force multipliers;29 the Soviets went down that route as an offset strategy. For the carrier-centered western navies, whilst a small increase in major surface combatants would no doubt be of use to provide flexibility of presence; for pure presence missions, vessels of OPV or corvette size would be more appropriate. These vessels are often cheaper, and as with the Soviet choice of cruisers in the Cold War, would not carry the risk of provoking an arms race, and would provide the hulls necessary for nations to have presence where they need it to be.

This is important, because if countries wish to be actors more often than reactors, they need to have as accurate as possible understanding of what is going on and be able to act quickly. A small ship may not have the status of a larger vessel, but its presence as the vanguard of the larger can enable it to have an impact out of all proportion.30 Events which are caught early can often be resolved more quickly by what is already there – thus according the situation less possibility for escalation. Presence can serve to increase predictability and stability which are always good for helping to maintain peace.

Dr. Clarke graduated with a PhD in War Studies from KCL in 2014, the thesis of which focused upon the Royal Navy’s development of naval aviation and aircraft carrier design in the 1920s and 1930s. He was supervised during this by Professor Andrew Lambert. Alongside this he has published works on the 1950s with British Naval History, and has also published on current events with European Geostrategy and the Telegraph online as part of the KCL Big Question series. He has maintained an interest in digital history, and is organizing, hosting, and editing a series of Falklands War veterans interviews for the Center for International Maritime Security and Phoenix Think Tank. Recent research outputs include presenting a paper at the National Maritime Museum’s 2016 conference on the ASW capabilities of the RNAS in WWI, and will be presenting a paper on the design & performance of Tribal Class Destroyers in WWII at the forthcoming BCMH (of which he is a member) New Researchers Conference.

Archival Sources

TNA: ADM 1/8672/227. 1924. “Light-Cruisers Emergency Construnction Progrmme.” Admiralty 1/8672/227. London: United Kingdom National Archives(Kew).

TNA: ADM 116/4109. 1940. “Battle of the River Plate: reports from Admiral Commanding and from HM Ships Ajax, Achilles and Exeter.” Admiralty 116/4109. London: United Kingdom National Archives (Kew).

TNA: ADM 116/4320. 1941. “Battle of the River Plate: British views on German pocket battleship Admiral Graf Spee in Montevideo harbour; visits to South America by HMS Ajax and HMS Achilles.” ADM 116/4320. London: United Kingdom National Archives (Kew).

TNA: ADM 116/4470. 1940. “Battle of the River Plate: messages and Foreign Office telegrams.” ADM 116/4470. London: United Kingdom National Archives (Kew).

TNA: ADM 223/714. 1959. “Translation of the 1949 Russian Book “Some Results of the Cruiser Operations of the German Fleet” by L. M. Eremeev – translated and distributed by RN Intelligence.” ADM 223/714. London: United Kingdom National Archives(Kew), 02 September.

TNA: ADM 239/533. 1960. “Supplementary Naval Intelligence Papers relation to Soviet & European Satellite Navies: Soviet Cruisers.” ADM 239/533. London: United Kingdom, National Archives (Kew), November.

TNA: ADM 239/821. 1959. “Particulars of Foreign War Vessels Volume 1: Soviet & European Satelite Navies.” ADM 239/821. London: United Kingdom National Archives (Kew), January.

TNA: DEFE 6/51/104. 1958. “Requirement for Cruisers East of Suez.” DEFE 6/51/104. London: United Kingdom National Archvies (Kew), 21 August.

TNA: FO 371/106559. 1953. “Soviet ships off the Shetlands; visit of Soviet cruiser Sverdlov to Spithead for the Coronation. Code NS file 1211.” FO 371/106559. London: United Kingdom National Archives(Kew).

TNA: PREM 11/1014. 1955. “Reconnaissance of Soviet cruisers by HMS Wave and RAF aircraft.” PREM 11/1014. London: United Kingdom National Archives(Kew).

References

1. Sergey Gorshkov (1980), p.229

2. Lambert (2008)

3. Cable, Gunboat Diplomacy 1919-1979, Political Applications of Limited Naval Force (1981)

4. TNA: ADM 1/8672/227 (1924) provides a good example of this, but for quick reference then Norman Friedman’s work British Cruisers; Two World Wars and After (2010) is also excellent

5. Signatories of the Washington Naval Limitation Treaty (2005)

6. Dismukes & McConnell (1979), p.93 & 96

7. Dismukes & McConnell (1979), pp.88-114 –this is Chapte 3, written by Charles C. Peterson, who credits much of the information used to the work of Anne Kelly Calhoun

8. TNA: FO 371/106559 (1953), and Dismukes & McConnell (1979), p.89

9. Dismukes & McConnell (1979), p.89

10. Ibid, pp.89-90

11. Ibid, p.94

12. Ibid, pp.91-2

13. Ibid, p.94

14. Ibid, p.100

15. Aldrich & Hopkins (2013), and Herman (1996)

16. Dismukes & McConnell (1979), pp.144-53

17. Ibid, pp.147

18. Ibid, pp.144

19. Rohwer & Monakov (2006), Polmar (1991), and TNA: ADM 223/714 (1959)

20. Massie (2005)

21. White (2009)

22. Pocock (2015)

23. W.B. Yeats The Second Coming

24. Cable, Gunboat Diplomacy 1919-1979, Political Applications of Limited Naval Force (1981)

25. Clarke, Protecting the Exclusive Economic Zones – Part I & Part II (2014), & Clarke, October 2013 Thoughts (Extended Thoughts): Time to Think Globally (2013)

26. Ministry of Defence & The Rt Hon Michael Fallon MP (2015), and Naval Today (2015)

27. BAE Systems (2015)

28. President Bartlet (Sorkin, 2000)

29. A. Clarke, Europe and the Future of Cruisers (2014)

30. Cable, Gunboat Diplomacy 1919-1979, Political Applications of Limited Naval Force (1981)

Featured Image: Soviet Navy Kirov-class cruiser. (Public Domain)