The following article originally appeared in The Naval War College Review and is republished with permission. It will be republished in three parts. Read it in its original form here.

By Christofer Waldenström

This article suggests a new perspective on the old problem of protecting ships at sea, for two reasons. First, although screen tactics and other defensive measures have been developed and used for many years, this new perspective will be useful in addressing two developments since the late nineteenth century: attackers are no longer just other ships but also aircraft, submarines, and, recently, missiles with very long ranges launched from the land; also, torpedo boats, coastal submarines, and mines have complicated operations in congested and archipelagic waters. The second reason for a new approach is that in order to support commanders in the problems of sea control we need to study the issues they encounter while solving them. This requires a description of each task that commanders have to do; without such a description it becomes difficult to determine which actions lead to increased control and which to loss of control, which in turn makes it harder to identify whether commanders are running into trouble and if so, why. The new analytical method introduced here represents an attempt at such a description. As such, it may enrich and extend traditional thinking about sea control and how to achieve it, especially in littoral waters.

Sea control is generally associated with the protection of shipping, and it refers normally either to a stationary patch of water, such as a strait, or to a region around a moving formation of ships. Today it is quite well understood how to protect such a region of water. To handle aircraft and missiles, defenses are organized in several layers, with an outer layer of combat air patrols to take out enemy aircraft before they can launch their weapons. Next is a zone where long- and short-range surface-to-air missiles take down missiles that the enemy manages to fire. Any “leakers” are to be handled by soft-kill and hardkill point defenses—for example, jammers, chaff, and close-in weapon systems. For submarines and surface vessels the logic is similar, but here maneuver is also an option. Since the attacking surface ship or submarine moves at about the same speed as the formation, it is possible to stay out of reach of the enemy. Maneuver seeks to deny detection and targeting and to force attacking surface ships and submarines to operate in ways in which they cannot muster enough strength to carry out their mission or are more easily detected.1

A prerequisite of a successful layered defense is detection of the enemy far enough out that all the layers get a chance to work. The restricted space of congested and archipelagic waters, however, may prevent the outer “strainers” from acting on the enemy. This gives small, heavily armed combatants opportunities to hide, perhaps among islands, and fire their weapons from cover, leaving only point defenses to deal with the oncoming missiles and torpedoes, with little room for maneuver.2 This increases the risk of saturation of defense systems and may allow weapons to penetrate.

The problems associated with archipelagic and coastal environments have been recognized since the introduction of the mobile torpedo.3 The torpedo gave small units the firepower to destroy ships much larger than themselves and made it possible for a small fleet to challenge a larger one, at least if it did not have to do so on the open ocean. To deal with such an inshore threat, the British naval historian and strategist Sir Julian Corbett suggested in 1911 that a “flotilla” of small combatants had to be introduced to deal with this type of warfare, because capital ships could no longer approach defended coasts, as they had when ships of the line dueled with forts.4 Today, the introduction of long-range missiles, mines, stealth design, and the ability to coordinate the efforts of land-, sea-, and air-based systems have further intensified this threat.5

Littoral environments seem to change the problem of sea control, at least in some aspects.6 Sensors, weapons, and tactics developed to handle threats on the open ocean may be less appropriate in congested and archipelagic waters. Radar and sonar returns are cluttered, missile seekers are confused, and targeting is complicated by the existence of islands and coastlines close to the ships to be protected. The land-sea environment introduces variables that make the sea control problem hard to solve using methods developed for an open ocean. As the uncertainties and intangibles mount up, quantitative approaches become less feasible, and we can only rely on human judgment.7 That is why it is important to study what commanders find difficult when executing sea-control missions in littoral environments.

It has been shown to be fruitful, when studying the problems people face when trying to solve a task, to have a model of the task that describes what the decision maker is required to do.8 Whether that task description takes the form of a document—a formal description or formula—or an expert, the approach is similar—you compare people’s behavior to the description and try to identify where and why they differ. Since experts differ, formal descriptions are preferable, if feasible. For the sea-control task, the description can either list the problems that the commander must solve in order to get ships safely to their destinations or define the variables of interest and the states they must be in for sea control to be considered established.

To get a description of what is required to establish sea control one can study what doctrine has to say. A major U.S. Navy doctrinal publication, Naval Warfare, characterizes sea control as one of the service’s core capabilities and states that it “requires control of the surface, subsurface, and airspace and relies upon naval forces’ maintaining superior capabilities and capacities in all sea-control operations. It is established through naval, joint, or combined operations designed to secure the use of ocean and littoral areas by one’s own forces and to prevent their use by the enemy.”9 British Maritime Doctrine has a similar description of sea control: “Sea control is the condition in which one has freedom of action to use the sea for one’s own purposes in specified areas and for specified periods of time and, where necessary, to deny or limit its use to the enemy. . . . Sea control includes the airspace above the surface and the water volume and seabed below.”10 A North Atlantic Treaty Organization publication, Allied Joint Maritime Operations, relates the level of control to the level of risk: “The level of sea control required will be a balance between the desired degree of freedom of action and the degree of acceptable risk.”11 Two academic analysts offer a more minimalistic view, arguing that tying the definition of sea control to specific military objectives creates contrasts between the challenges posed by, for example, littoral environments and blue-water environments.12 To accommodate these contrasts and allow for the full range of operations, they put forward “the use of the sea as a maneuver space to achieve military objectives” as a definition of sea control.

However, two issues make it hard to use these descriptions for studying the problems commanders face in sea control tasks. To say so is not to criticize their doctrinal utility but rather to point out that for the purposes of this article, their meanings need to be expressed in a somewhat more formal way. The first issue is related to how the definitions describe when sea control has been established. All these definitions describe sea control from a general perspective, as a state, implying a line between when that state has been reached and when it has not. As result, it would be possible to use such a description to determine whether sea control has been established, at least in theory. A necessary precondition of such a description, however, is that it contain concepts—or to be more specific, a set of variables—that can be observed from the outside. For each variable there must be specified the value it must have, or the condition it must be in, in order to say that the overall state has been reached. Only then are we able to use the definition to measure whether a commander has succeeded in establishing sea control. The second issue regards the “general,” “outside” perspective that characterizes all these descriptions—a conceptual view, detached from the environment, the task, and the decision maker. In a sea-control task, however, several factors, variables, need to be considered in order to determine the degree to which the commander has managed to solve it: geography, type and duration of the operation, the enemy’s units and weapons, own resources, and the size of the region are just a few examples. A description covering all possible aspects of sea control and all possible situations would probably be quite complicated, containing many variables and many states; new variables not considered at the beginning might even have to be added as they arise.13 This is not an attractive situation for a scientific concept. Another approach would go in the other direction, stripping the definition of variables and formulating it on a very general level (the academic definition cited above is such an attempt).14 Such a definition covers a wide range of situations, but it is not very specific and provides no guidance as to when sea control has been established.

It would seem, then, that defining sea control from a general perspective is not helpful for present purposes. The point is to not separate the definition of sea control from the person trying to achieve it, or from the environment, or from the task. Such a definition would assume the perspective of the commander, describe sea control as a task that the commander has to accomplish, and lay out what is required to accomplish that task.15 Such a definition could, as we have postulated about the analytical definition we need, either describe the problems that the commander must solve in order to protect the ships or be a representation of the sea-control task. Such a description would allow systematic investigation of the effects of different tasks and different environments on the commander’s ability to establish sea control.

In fact, I argue, to investigate the concept empirically, sea control is best described from the inside. Taking the perspective of commanders trying to achieve control makes it possible to investigate systematically the problems they face and in turn, perhaps, to derive guidance for the design of training and support systems. The point of departure for such a description is the idea that securing control at sea is analogous to establishing a “field of safe travel,” a concept that has been proposed to describe the behavior of automobile drivers.16 This approach can be useful for investigating the problems commanders at sea face, and it may enrich and extend traditional thinking about sea control and how to achieve it, especially in littoral waters.

The Field of Safe Travel

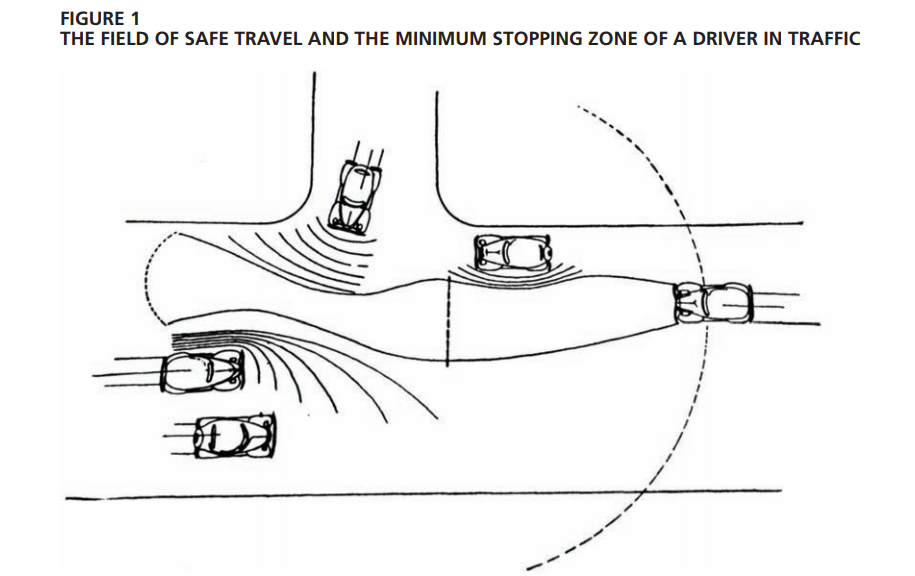

Driving a car has been described analytically as locomotion through a terrain or a field of space. The primitive function of locomotion is to move an individual from one point of space to another, the “destination.” In the process obstacles are met, and locomotion must be adapted to avoid them—collision may lead to bodily injury. Locomotion by some device, such as a vehicle, is, at this level of abstraction, no different from walking, and accordingly it is chiefly guided by vision. This guidance is given in terms of a path within the visual field of the individual, such that obstacles are avoided and the destination is ultimately reached.

The visual field of a driver is selective, in that the elements of the field that are pertinent to locomotion stand out and are attended to, while irrelevant elements recede into the background. The most important part of this pertinent field is the road. It is within the boundaries of the road that the “field of safe travel” exists.17 The field of safe travel is indefinitely bounded and at any given moment comprises all the possible paths that the car may take unimpeded (see figure 1). The field of safe travel can be viewed as a “tongue” that sticks out along the road in front of the car. Its boundaries are determined by objects that should be avoided. An object has valence, positive or negative, in the sense that we want to move toward some (positive valence) and away from others (negative valence). Objects of negative valence have a sort of halo of avoidance, which can be represented by “lines of clearance” surrounding it. The closer to the object the line is, the greater the intensity of avoidance it represents. The field of safe travel itself has positive valence, the more so along its midline.18

The field of safe travel is a spatial field. It is, however, not fixed in physical space but moves with the car through space. The field is not merely a subjective experience of the driver but exists objectively as an actual field in which the car can operate safely, whether or not the driver is aware of it. During locomotion it changes constantly as the road turns and twists. It elongates and contracts, widens and narrows, as objects encroach on its boundaries.

It is now possible to investigate how the concept of a “field of safe travel” applies to naval warfare. As stated above, the purpose of sea control is to take control of maritime communications, whether for commercial shipping or naval forces. The practical problem for a commander is consequently to protect commercial vessels and warships as they move toward their destinations. These ships will be referred to as “high-value units.”

The analogy is straightforward: to make sure that the high-value units get safely to their destinations the commander must create a “field of safe travel” where they can move without risk of being sunk. At the simplest level, without the complication of hostile opposition, the problem of maneuvering a high-value unit is exactly the same as that of driving a car: make sure that it gets to its destination without running into something (that is, for a vessel, colliding or running aground). As such, there is no difference between a high-value unit’s field of safe travel and an automobile’s.

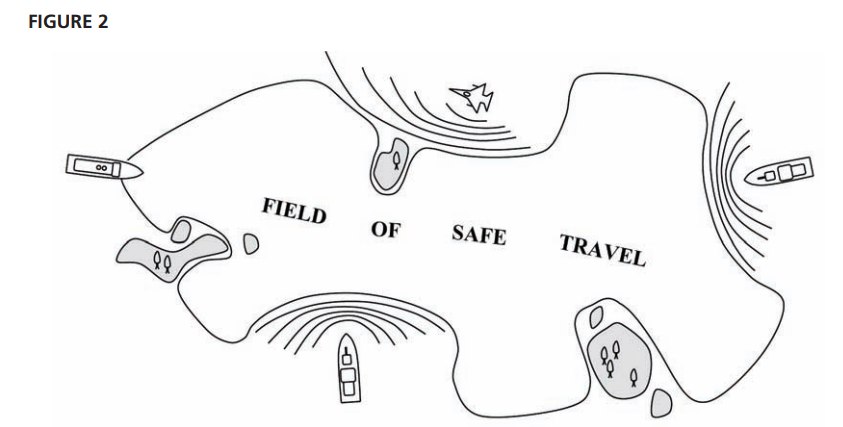

The fields of individual ships are, however, not of interest here and will not be further discussed; our focus is the field of the commander of the naval operation. In that field, the most pertinent element of the environment is not the terrain (though coasts and islands delimit how the ships can move) but the enemy. Consequently, the boundaries of the commander’s field of safe travel are determined most importantly by enemy units that threaten to sink the commander’s high-value units (see figure 2). In contrast to fixed objects in a driver’s field of safe travel, islands and coastlines may actually have positive valences for a commander, as they can offer protection. Nevertheless, the definition of the field remains the same: the commander’s field of safe travel comprises all the possible paths that the high-value units can take unimpeded.

Though the analogy is straightforward, there are several differences between the driver’s field of safe travel and that of the commander. First, the driver of a car has limited ability to influence the shape of the field of safe travel and can only see and react to obstacles that encroach on the field. Commanders, on the other hand, can actively shape the field of safe travel and have powerful means to do so: they can scout threatening areas to determine whether enemy units are present, and if they detect a threat they can eliminate it by applying deadly force. Second, the commander is up against an enemy who means to do harm. An opponent who uses cover and deception can make it more difficult to establish the requisite field.

Third, the commander’s field of safe travel cannot, like the field of a driver of an automobile, be directly perceived; it is too vast. Instead, the commander must derive the field, using data provided by sensors carried by the units in the force. As will be seen later, this difference complicates matters for the commander. Nevertheless, it is important at this point to notice that the field of safe travel is not merely a subjective experience of the commander but exists as an objective field where the commander’s ships can move safely.

The Minimum Safety Zone

In driving, collisions are avoided by one of two methods—changing the direction or stopping the locomotion.19 Changing direction is done by steering. Sometimes, however, the field of safe travel is cut off, for example, when another car turns onto the road from a side street. In these situations steering is not enough, and the driver has to slow down to avoid a collision. Another field concept describes how drivers decelerate—the “minimum stopping zone,” which denotes the minimum spatial field a driver needs to bring the vehicle to a stop (see figure 1).20 Deceleration (or the degree of braking) is proportional to the speed at which the forward boundary of the field of safe travel approaches the edge of the minimum stopping zone.

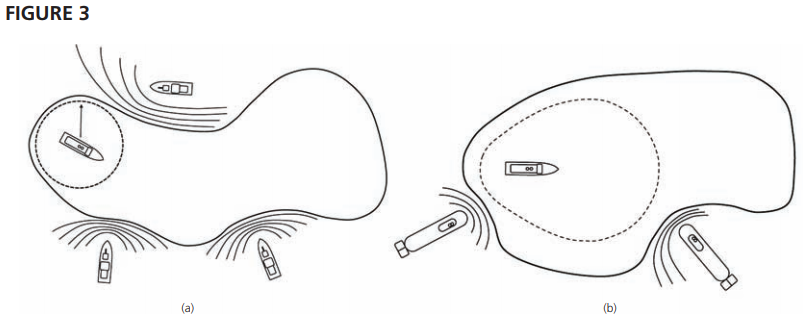

For the commander of a naval operation, the field of safe travel is delimited not only by the terrain but also by, most importantly, threatening enemy units. The commander uses a related field concept to determine whether action is needed to prevent the high-value units from being sunk—the “minimum safety zone” (see figure 3). The minimum safety zone is a field the size of which is determined by the range of a specific enemy weapon; there exists one minimum safety zone for each type of enemy weapon. The field denotes how close to the high-value units an enemy unit carrying that weapon can be allowed before the enemy unit can sink the high-value units using that specific weapon.21 For example, suppose an enemy ship has an antiship gun with a range of ten thousand meters. In this case, the minimum safety zone for that gun would be a circle with a radius of ten thousand meters around each high-value unit.

From this it follows that there exist as many fields of safe travel as there are minimum safety zones; minimum safety zones and fields of safe travel always come in pairs. For example, the enemy may have a long-range antiship missile that can be fired from surface ships and a medium-range torpedo that can be fired from submarines. This creates two separate pairs of fields of safe travel and minimum safety zones—one for the antiship missile and one for the torpedo. Consequently, to make sure that the high-value unit is not sunk, each minimum safety zone must be completely contained within its corresponding field of safe travel for the duration of the voyage.

Also, the shape of the minimum safety zone varies according to the type of weapon it represents (see figure 3). The shape is determined by the relative speeds of the weapon and the target and their relative headings when the weapon is fired. Suppose a high-speed antiship missile is fired toward a slow-moving high-value unit (see figure 3a). It will take the missile about five minutes to reach its target if the speed of the missile and the range to the target are, respectively, 645 knots and about fifty-four nautical miles. The distance the high-value unit can move during this time at twenty-five knots is about four thousand meters. Thus, the difference in time between when the missile is fired with the high-value unit heading toward it or moving away is negligible; the minimum safety zone can be considered circular. Now consider firing a medium-range torpedo at the same high-value unit. The torpedo has a speed of, say, fifty knots and a range of 25 nautical miles. If the enemy unit fires this torpedo when the high-value unit is heading toward it the theoretical range becomes about thirty-seven nautical miles (it takes thirty minutes for the torpedo to travel its maximum distance, in which time the high-value unit can move 12.5 nautical miles closer). On the other hand, if it fires when the high-value unit is moving away, the range drops to only 12.5 nautical miles. Thus, the shape of the minimum safety zone for the torpedo will be more or less elliptical, with the high-value unit positioned toward its far end (see figure 3b).

What minimum safety zone the commander uses when encountering a new contact depends on how well the contact is classified. If the commander knows what type of enemy unit is approaching, the proper, specific minimum safety zone is applied. If there is uncertainty, the commander must assume the largest minimum safety zone for that class of contacts. For example, if the commander knows that only surface ships can carry long-range antiship missiles, the minimum safety zone for those missiles must be assumed for an unidentified radar contact—that is, of the class of surface contacts. For the submarine screen, however, the minimum safety zone can be based on the medium-range torpedo—the class of underwater contacts. For the driver of an automobile, braking is a reaction to the threat of crashing into an object and it is initiated when the forward boundary of the field of safe travel recedes toward the minimum stopping zone. In a similar way, the commander of a naval operation reacts when the field of safe travel recedes toward the minimum safety zone—that is, when a threat develops toward the high-value units. In contrast to the automobile driver, however, the commander has three ways of handling a threat: move the high-value units away from the threat, order subordinate units to take action against the threat, or receive the attack and defend. Either way, to establish whether a threat is developing, the commander must be able to determine whether the field of safe travel is receding toward the minimum safety zone.

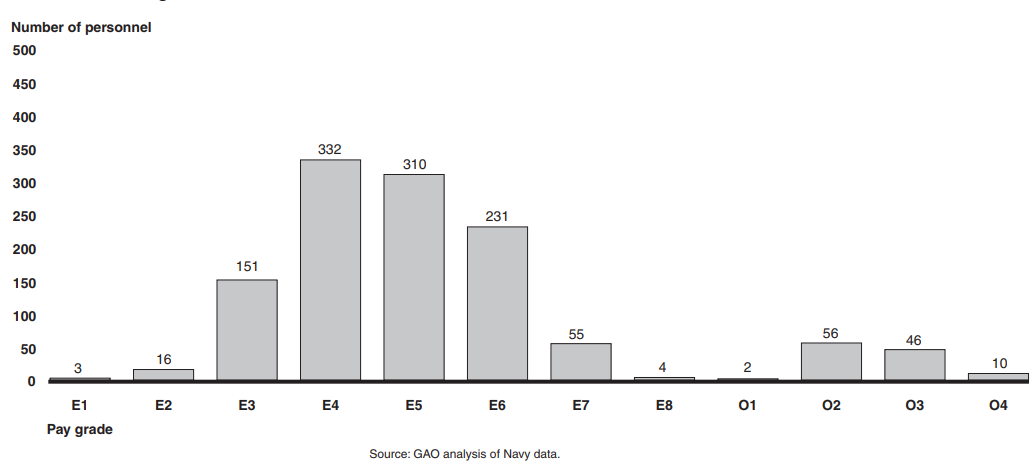

Dr. Waldenström works at the Institution of War Studies at the Swedish National Defence College. He is an officer in the Swedish Navy and holds an MSc in computer science and a PhD in computer and systems sciences. His dissertation focused on human factors in command and control and investigated a support system for naval warfare tasks. Currently he is working as lead scientist at the school’s war-gaming section, and his research focuses on learning aspects of war games.

References

1. Robert C. Rubel, “Talking about Sea Control,” Naval War College Review 63, no. 4 (Autumn 2010), pp. 38–47.

2. Ibid.; Wayne P. Hughes, Jr., Fleet Tactics and Coastal Combat (Annapolis, Md.: Naval Institute Press, 2000).

3. Sir Julian Corbett, Some Principles of Maritime Strategy (1911; repr. Annapolis, Md.: Naval Institute Press, 1988), pp. 122–24.

4. Ibid.

5. For descriptions of littoral navies, see, among others, J. Børresen, “The Seapower of the Coastal State,” Journal of Strategic Studies 17,

no. 1 (1994), pp. 148–75; Tim Sloth Joergensen, “U.S. Navy Operations in Littoral Waters: 2000 and Beyond,” Naval War College Review

51, no. 2 (Spring 1998), pp. 20–29.

6. Hughes, Fleet Tactics and Coastal Combat; Milan Vego, Naval Strategy and Operations in Narrow Seas, 2nd ed. (Portland, Ore.: Frank Cass, 1999); John F. G. Wade, “Navy Tactics, Doctrine, and Training Requirements for Littoral Warfare” (thesis, U.S. Naval Postgraduate School, Monterey, Calif., June 1996); V. Addison and D. Dominy, “Got Sea Control?,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 136, no. 3

(2010).

7. See the discussion of the C4ISR (command, control, communications, computers, intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance) system as an artifact in Berndt Brehmer, “Command and Control Research Is a ‘Science of the Artificial’” (paper delivered to the fifteenth International Command and Control Research and Technology Symposium, Seattle, Wash., 2010).

8. An example that has generated a Nobel Prize winner is “heuristics and biases” decisionmaking research, where human judgment is compared to statistical models. See D. Kahneman, P. Slovic, and A. Tversky, Judgment under Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases (New York: Cambridge Univ. Press, 1982); and T. Gilovich, D. Griffin, and D. Kahneman, eds., Heuristics and Biases (New York: Cambridge Univ. Press, 2002). For a more general overview,

see, for example, Paul R. Kleindorfer, Howard C. Kunreuther, and Paul J. Schoemaker, Decision Sciences: An Integrative Approach (Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge Univ. Press, 1993).

9. U.S. Navy Dept., Naval Warfare, Naval Doctrine Publication 1 (Washington, D.C.: 2010) [hereafter NDP-1], p. 28.

10. Ministry of Defence, British Maritime Doctrine (BR1806), 3rd ed. (Norwich, U.K.: by command of the Defence Council, 2004), pp. 41–42.

11. North Atlantic Treaty Organization, Allied Joint Maritime Operations, AJP 3.1 (Brussels: NATO Standardization Agency, 2004), chap. 1, p. 8.

12. Addison and Dominy, “Got Sea Control?”

13. As it was necessary for Ptolemy to introduce epicycles in order to handle the irregular movement of planets in his geocentric description of the solar system.

14. Addison and Dominy, “Got Sea Control?”

15. There are several analyses that describe the kinds of missions a commander has to execute in order to achieve sea control. See, for example, Frank Uhlig, “How Navies Fight, and Why,” Naval War College Review NWC_Winter2013Review.indd 98 11/1/12 10:57 AM 22

Naval War College Review, Vol. 66 [2013], No. 1, Art. 7

https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/nwc-review/vol66/iss1/7

WALDENSTRÖM 99 48, no. 1 (Winter 1995), pp. 34–49; Uhlig,

“The Constants of Naval Warfare,” Naval War College Review 50, no. 2 (Spring 1997), pp. 92–105; and NDP-1. What missions have to be executed, however, do not constitute a description of what has to be accomplished in order to establish sea control. The missions that can be executed represent the means

available to establish sea control—that is, the commander’s ways of bringing about the state of sea control.

16. J. Gibson and L. Crooks, “A Theoretical Field Analysis of Automobile-Driving,” American Journal of Psychology 51, no. 3 (July 1938), pp.

453–71.

17. Ibid., p. 454.

18. The concept of ”valence” is from ibid., p. 455.

19. Ibid., p. 456.

20. Ibid., p. 457.

21. The “minimum safety zone” is just another term describing how far out from the field of safe travel an enemy contact starts to encroach on it. To use the field and anchor it to the high-value units is convenient, however, and makes it possible to use the same concept for all enemy weapons, antiship missiles as well as mines. Further, the observations of naval officers when they solve sea-control tasks have revealed that they use tools in the command-and-control systems on board their ships to visualize these zones—circular regions around high-value units or corridors where high-value units will move.

Featured Image: ATLANTIC OCEAN (May 13, 2010) Operations Specialist 3rd Class Gregory L. Gray mans his station in the Combat Direction Center aboard the aircraft carrier USS Enterprise (CVN 65). (U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 3rd Class Brooks B. Patton Jr./Released)