Read Part One here.

“It shall be the policy of the United States to have available, as soon as practicable, not fewer than 355 battle force ships.”

-Section 1025, Para (A) of the National Defense Authorization Act for FY2018 (FY18 NDAA)

“Battle force ships are commissioned United States Ship (USS) warships capable of contributing to combat operations, or a United States Naval Ship that contributes directly to Navy warfighting or support missions, and shall be maintained in the Naval Vessel Register” –SECNAVINST 5030.8C

By Keith Patton

Flotillas and Ants Versus the Elephant

Current shipbuilding plans expand the fleet, but no consideration is given to mass producing a warship smaller than the “small surface combatant” role filled by the LCS and new frigates, which are larger than World War II destroyers. The Navy could consider even smaller vessels, less than 100m. These would be of a few different designs, or perhaps one design that can be optimized when constructed for different mission areas. One variant could be an armed replacement for the T-AGOs as they age out of service and to expand their numbers. Another could be a close-in ASW escort for ships. A third would be a surface strike platform with either or both land-attack and anti-ship missiles. The main goals would be ship designs that are compact, can be built in additional shipyards besides the current ones supporting the U.S. fleet, and provide needed niche capabilities. A flotilla of smaller vessels can be in more places at once to show the flag, be part of the deterrence force suggested as an alternative operating concept, and any losses in combat are more easily tolerated compared to large, multi-role vessels. Training would be streamlined as each crew would only have a few missions to focus on. Being able to use more shipyards to produce them would also allow reaching a 355 ship force sooner. However, this would break the mold of building most U.S. surface combatants as multi-mission platforms.

A more radical idea to save costs and accomplish the above is to stop carrier production after the last Ford on order. The existing carrier fleet would still exist, in dwindling numbers, for decades to come and still outnumber any projected rival carrier fleet in size and capability. The Navy has already floated the idea of cancelling the refueling of the carrier Truman as a cost savings measure. By block buying the last two Fords and retiring Truman early, a significant savings is achieved. SECDEF Mattis wanted the savings rolled into unmanned systems (discussed below) and other new capabilities. Additionally, the USN does not have sufficient air wings to equip all its carriers today. For the cost of a Ford class, including crew, multiple DDGs or perhaps a score of small combatants could be procured. They would likely also be produced much faster. However, while this idea would help expand the size of the U.S. fleet quickly, it would not do it within the next decade because the existing Fords are already on the way within that timeframe. This would simply allow a bigger fleet, more economically, in future decades. As such, it might be a pressure release against decisions that expand the fleet sooner but less economically. However, considering the House Armed Services Seapower Subcomitteee Chairman announced the idea of retiring a carrier early is a non-starter, the political obstacles to early retirement or cancelling future carrier production are enormous.

The Ghost Fleet

The critical first step in a naval war is locating targets – the battle of Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance (ISR) and Counter-ISR (C-ISR). You cannot hit what you can’t find. The submarine is the pinnacle of this concept, but modern combatants are becoming stealthier in an attempt to reduce the ranges they can be detected from. An example is the Zumwalt destroyers, which reportedly have such a small radar cross-section they are likely to be seen visually before being detected on radar.

However, there is another and perhaps cheaper approach to not being detected – flooding the adversaries ISR network. While jamming systems can deny an adversary information, they also provide it by making it clear that something is producing the jamming. Since high power jamming systems are located on warships and aircraft, the source of the jamming is a worthwhile target, and jamming is itself an active emission. Decoy systems, however, produce a false target. If there are ten contacts, and only one is a warship worthy of expending weapons against, the adversary must sort through all of the decoys to ensure they target the correct contact. This takes time and energy, allowing the warship to gain the upper hand. Alternatively, the adversary could attack all ten contacts. However, they might not have the resources available to attack all of them effectively, and may be expending great effort for low returns.

Does a battle force ship need to be manned? It is not listed in the definition as a requirement. Since a battle force ship must contribute “directly to Navy warfighting,” small, minimally manned or unmanned decoy and jamming vessels would count. DARPA’s Sea Hunter anti-submarine warfare continuous trail unmanned vessel (ACTUV) cold serve as a prototype example. Instead of following an adversary submarine, it could have signal arrays and deployable decoy payloads that could produce radar or radio emissions to mimic a warship. If sufficient power was available, it could also produce high power radar or jamming signals to attract an adversary’s attention. If the Sea Hunter is not cost effective enough, basic merchant hulls could be procured for the same purpose. They could be visually altered to resemble Navy logistics vessels, have noisemakers to better mimic high-value targets, and even periodically launch a drone helicopter to simulate manned flight operations. If not completely unmanned due to feasibility issues of command and control, they could be minimally manned with crew mostly living and working in an armored citadel-like structure, and if the decoy ship succeeds in its mission and draws fire, they are at reduced risk. In some ways this is like the Q-ships that were designed to lure in a submarine and survive torpedo damage to fight back. Procuring 50-100 civilian construction “Ghost Ships” to stretch an adversary’s ISR network with numerous false or less valuable contacts would raise the battle force count, increase fleet resilience, and help protect traditional warships.

Armed Merchantmen

The idea of armed merchant ships is not new. While the 1856 Treaty of Paris continued a prohibition on privateering (privately owned ships permitted by its government to wage war), as noted above military crews were placed in command of armed merchants (Q-ships) designed to lure in U-boats and the U.S. placed the U.S. Navy Armed Guard detachments on civilian ships to operate defensive weapons. During the Cold War, the United States armed its supply and auxiliary vessels with defensive weapons. This practice was stopped as a cost savings measure. Transferring auxiliaries from regular Navy to Maritime Sealift Command and civilian mariners saved hundreds of millions of dollars annually, never mind the cost savings of not having to equip them with expensive weapons and train personnel in their use. Such policy decisions could be reversed and the auxiliaries placed under military command, and then armed again to provide basic self-defense capability. However, this does not increase the count of battle force ships.

Mass-produced commercial hulls could provide a way to quickly increase battle force ship numbers, particularly as escorts or strike platforms. Container ships can carry thousands of twenty-foot equivalent unit (TEU) standardized cargo containers. 100 TEUs could contain the combat system and power requirements equivalent to a modern frigate. Israel has demonstrated a containerized ballistic missile launched from a cargo vessel, and Russia has advertised containerized versions of its Club-K missile family. Containerized U.S. missiles have been suggested by a former Dean of the U.S. Naval War College. It has also been suggested that commercial ships could form the basis of a naval surface fire support platform. Another way of looking at this is that the combat system would be independent of the hull. The cargo vessel would be carrying a capability akin to AEGIS ashore, manned by NAVY personnel or a modern equivalent of the U.S. Navy Armed Guard. These would not be true “arsenal ships” as conceived of in the 90s. They might only carry 32-64 missiles (standard Mk.41 VLS configurations) rather than 500. However, a mix of defensive or long-range strike weapons would free traditional warships of some missions. The slower design speed of commercial vessels would not make them valuable carrier escorts, and they may not be as capable and certainly not as stealthy as modern U.S. surface combatants, but a number of these vessels could augment capabilities like long-range strike, ballistic missile defense, or act as escorts for similarly large and slow logistics vessels. Also, these hulls could be produced very quickly and probably would require lower manning than traditional warships. The 2018 GAO Shipbuilding report showed that the T-EPF and T-ESD designs, largely commercial in nature, were the only Navy shipbuilding programs of the last decade to come in under budget.1

Warship Equivalents

Another line of thought is considering when a Battle Force Ship is not a ship. Can the Navy “break the mold” in the definition of a ship and provide a 355-battle force ship equivalent fleet without 355 actual vessels?

Coastal Artillery Corps

The U.S. Army used to have a prestigious coastal artillery corps. The coasts of the United States have many examples of old, fixed fortifications operated by the U.S. Army for harbor defense. As airpower developed, these defenses became casemented to protect against air attack, or mobile to complicate an adversary’s ability to locate and target them. A modern Army (or USMC) Coastal Defense Corps would have to employ mobile systems. This would not just be to increase their survivability but to allow them to be forward deployed or surged in a crisis or war. The anti-ship capability of the land-based HIMARs rocket was tested during RIMPAC 2018 and future ATACMs rounds are planned to have much longer range and an anti-ship seeker capability. The venerable Harpoon anti-ship missile is already used as a coastal defense cruise missile (CDCM) by many nations and is being considered for U.S. Army and USMC use. The Norwegian Strike Missile or LRASM missile are also potential contenders for a CDCM, as would be the planned Maritime Strike Tomahawk now that the U.S. announced plans to withdraw from the Intermediate Range Nuclear Forces Treaty. Tomahawk had a land-based variant until that treaty was signed, and the 2017 NDA authorized funds to study a new long-range ground-launched cruise missile. Could a battery of mobile CDCM’s be a “warship equivalent”?

The advantage of these land-based weapons is they could be deployed to allied territory and dispersed to avoid targeting. Their range rings could cover a significant amount of water space, and a camouflaged and mobile land-based weapon would be more survivable than a ship, as well as being more cost effective overall and faster to transport to a theater by air should speed be needed. Batteries of land based CDCM, possibly with their own SAM capabilities as well, could provide a ship equivalent asset for sea denial missions.

Patrol Bombers

The U.S. Navy’s shipbuilding plan to reach a 355 ship Navy (or 335 by FY48), doesn’t address naval aviation specifically. It can be assumed sufficient helicopters and air wings are acquired to support the aviation capable ships in the fleet. However, can the return of a Navy bomber force act as a ship equivalent? The Navy did field bombers for patrol and strike in WWII – VB squadrons.

This move would both break the mold of a 355-ship navy being composed of ships, and infringe somewhat on the U.S. Air Force mission area. However, USAF bombers are generally optimized for strike against land targets and tasked for such a long-range power projection missions. While USAF bombers can employ anti-ship missiles and drop sea mines, these capabilities were allowed to atrophy for decades and such missions would pull USAF bomber resources away from other traditional USAF missions. A naval bomber would not need deep penetration capability. A naval bomber would be a simpler missile truck to get into position to launch long-range anti-ship missiles or mine a chokepoint that was not protected by adversary air defenses. While the P-8 is capable of these missions, it is more a reconnaissance, sub hunting and patrol aircraft with a relatively limited weapons load compared to a true bomber.

Dedicated VB squadrons, either manned or perhaps as a large armed drone, could provide a long-range maritime strike capability similar to Russia or Chinese maritime bomber squadrons. They could greatly augment the firepower of a surface action group or even a carrier air wing. Their long-range would allow them to rapidly shift missions across an AOR in a way surface vessels cannot. Additionally, unlike surface vessels, they can quickly rearm. While warships provide presence, sustained ISR, and other critical naval capabilities, VB (or VUB) squadrons would provide maritime strike capabilities and deterrent capabilities when actual ship hulls are not available. While USAF bombers could also do this, aircraft directly manned, trained, and equipped by the Navy and optimized for the maritime domain would seem more efficient and in keeping with increasing fleet power to a 355-ship equivalent on a quicker timeline.

License or Purchase Foreign Designs

If current United State battle force shipbuilding cannot produce the required quantity of vessels, could foreign designs be licensed or outright purchased to meet the needs of a 355 ship Navy? Some options would require a rethinking of U.S. procurement policy and laws. 41 USC 8302, amended most recently by H.R.904, is a U.S. law, more commonly called the “Buy American Act” that requires anything the U.S. government buys be made in the United States. The Presidential Executive Order of 18 April 2017 directed government agencies to minimize exemptions to 41 USC 8302. The law does have two exceptions that could allow purchase of foreign battle force ships. One is that items procured for use outside the United States are exempt. It can be argued warships, and indeed most of the U.S. military, is intended for use outside the United States. Under the concept of regionally designed ships, covered earlier, these warships could be procured from the countries they are forward based in and intended for the defense of. The second is when there is insufficient U.S. production capacity. Since U.S. shipbuilding cannot ramp up to produce a 355 ship navy in a few years, this criteria is met.

The Royal Navy’s Queen Elizabeth-class carrier, while not as capable as a U.S. nuclear-powered carrier, still provides a significant aviation capability at a significant cost savings compared to U.S. nuclear carriers. Procurement of a third hull, before the line goes completely cold, would allow an increase in the Navy carrier fleet faster than if domestic carrier building was the sole source. For a time, the Queen Elizabeth class was planned to have catapults and arresting gear like U.S. carriers, a capability which would make them significantly more capable, at increased cost. In either short take off, vertical landing (STOVL) or Catapult Assisted Takeoff and Barrier Arrested Recover (CATOBAR) configuration, a Queen Elizabeth-class would add to Navy capabilities and battle force ships count.

While an additional aircraft carrier would increase the battle force ship count, it would require appropriate escort and supporting vessels. Additionally, as noted above, the Navy seems to have a greater need for escorts and smaller combatants that can be geographically dispersed for presence, shadowing, or ISR missions, or used in surface action groups (SAG). The new Navy frigate program will eventually produce some ships of this nature, but to rapidly achieve a 355 ship navy, already available foreign designs should be considered. The Israeli Sa’ar V and VI corvettes are 1,000-2,000 thousand tons, have small crew sizes, deck guns, and 32 defensive VLS missiles as well as deck-mounted anti-ship missiles. The Sa’ar V ships were even built in the United States by Huntington Ingalls. A U.S. corvette built to these designs would be well-suited for operations in the 5th Fleet or 6th Fleet AORs and possibly as part of an offensive SAG in PACOM. Both Korea and Japan produce Arleigh-Burke-like warships, and there are multiple solid frigate designs available in allied countries. Using foreign builders would allow a rapid buildup and shield U.S. industry from a boom-bust impact. However, it would be politically challenging. There are also fewer options for nuclear submarines.

Diesel AIP

Accelerated U.S. shipbuilding plans do not reach the requested number of SSNs in the fleet until 2042. Indeed, under current shipbuilding plans, the Navy is looking at a valley in attack submarine strength between FY25 and FY36, reaching a low of 41 SSNs in FY30.2 This is a 20 percent decrease in SSN strength as the Navy attempts to reach a congressionally-mandated goal for a 20 percent increase. There appears to be no way for the U.S. to achieve desired submarine numbers for a 355 ship fleet, with current levels of U.S. production.

Several allies produce extremely effective conventional submarines, or conventional diesel submarines (SSP) augmented with Air Independent Propulsion (AIP). These submarines are significantly smaller and cheaper than U.S. nuclear powered submarines. The U.S. has long preferred nuclear submarines due to their higher sustained speeds for transit to a theater, on station times only limited by consumables, and no need to raise a snorkel above the water for a period every few days. However, if forward deployed and perhaps built in the countries they are deployed in, some of these limitations can be mitigated. Soryu-class AIP subs built and operated from Japan would be able to arrive rapidly on station in Asian waters and contribute to the battle force. German Type 212 could provide a similar option in Europe. Both provide critical capabilities in their respective areas, and multiple SSPs can be built and manned for cost of a single U.S. SSN while also being available far sooner than any potential acceleration of U.S. submarine shipbuilding.

The Truly Radical

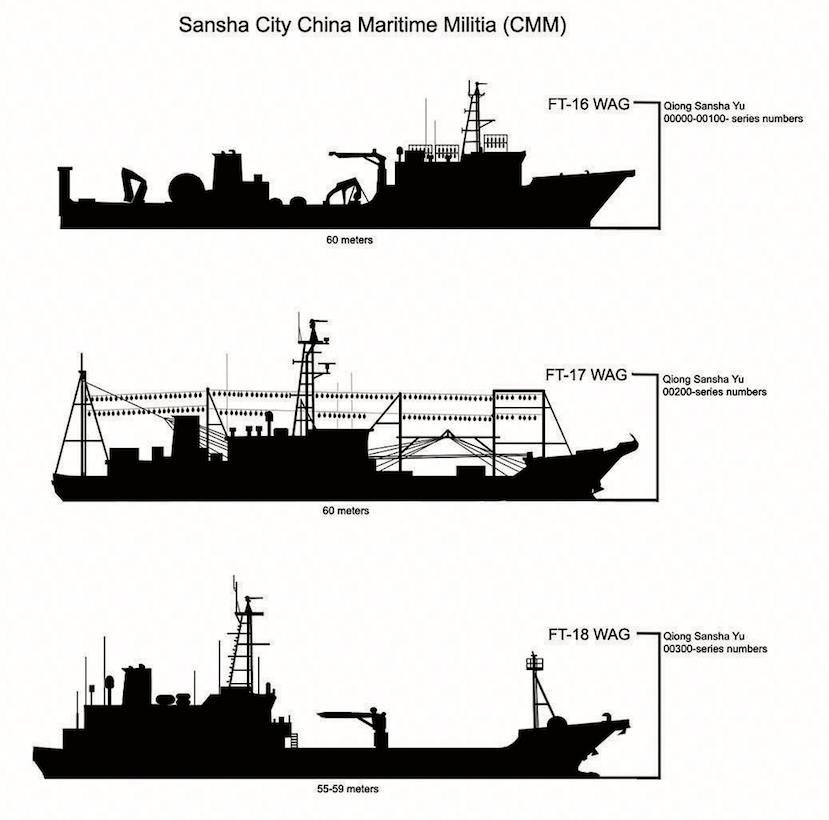

A final, truly radical idea, is the establishment of a U.S. Navy Foreign Legion. Two different options could be considered. One would be a mercenary, small boat operations force akin to Chinese Maritime Militia, but more overtly armed and associated with the U.S. military. These could be locals recruited into service, or contractors from the United States. Like the French Foreign Legion, they would have to be an official part of the U.S. military despite their foreign status. This would allow them to operate ships counted as battle force ships and under the laws of armed conflict. The small craft, while perhaps useful for some lower end missions, would not count as battle force ships. This idea seems to help more with the manning requirements of a 355 ship navy than with actually achieving the ship count sooner.

An alternate method would to procure foreign warships, as discussed above, and crew them with the US Navy Foreign Legion crews. These would take the form of non-citizens, but under U.S. command and control. In some ways it would be like the Japanese building a submarine or warship, crewing it, and then seconding it to the U.S. Navy. This would both raise battle force ship count and solve the man power problem simultaneously. However, it would also be very “mold breaking” in that the U.S. hasn’t done such a thing with its Navy before, and use of foreign citizens as full crews would be controversial aside from the controversy of non-U.S. built warships. Foreign nationals already serve in the U.S. military, but not a dedicated formations.

Conclusion

This has been an attempt to capture some of the interesting thoughts, from two separate working groups, on how the U.S. Navy could achieve a 355 battle force ship Navy sooner than current plans predict. Several of the ideas above could increase the battle force size, but come at significant economic or political risk to achieving them, like using older or reactivated ships or buying foreign warships possibly with foreign crews. Others challenge Navy established practices by phasing out carriers, giving up SSBNs, or focusing on smaller combatants. Some challenge the idea of what a warship is, what can be counted and what should count as a warship. Is 355 correct? Or is the equivalent capability of 355 ships desired?

Right now, the Navy has presented a plan to Congress. There may be no need for the above. But the global political situation is rapidly changing, especially with worsening relations with increasingly assertive great power rivals, and the urgent need for a 355-ship Navy could very well come sooner rather than later.

CDR Patton is deputy chairman for the U.S. Naval War College’s Strategic and Operational Research (SORD) Department. SORD produces innovative strategic research and analysis for the U.S. Navy, the Department of Defense, and the broader national security community. CDR Patton was commissioned in 1995 from Tufts University NROTC, with degrees in history and political science and has served four tours conducting airborne nuclear command and control missions aboard the US Navy E-6B Mercury aircraft, and two tours as Tactical Action Officer (TAO) and Combat Direction Center Officer (CDCO) aboard the carriers USS KITTY HAWK and USS NIMITZ.

The opinions and ideas above do not necessarily represent those of the Department of Defense, U.S. Navy, or the Naval War College. The ideas expressed here do not necessarily reflect those of the principal author either. They were drawn from the Breaking the Mold II workshop held at the U.S. Naval War College with invited participants from military, industry, government and academic institutions. The workshop was held under the Chatham House Rule, so these ideas will not be attributed to their originator. Some ideas were specific enough that they are not included here because the idea itself might identify the originator and violate the Chatham House rule.

References

1. “Navy Shipbuilding,” June 2018, pg. 8

2. Ronald O’Rourke, “Options and Considerations for Achieving a 355-Ship Navy” July 25, 2017. Pg. 6

Featured Image: ATLANTIC OCEAN (Dec. 23, 2018) MV-22 Ospreys assigned to Marine Medium Tiltrotor Squadron (VMM) 264 (Reinforced) prepare to launch from the flight deck of the Wasp-class amphibious assault ship USS Kearsarge (LHD 3) during night flight operations. (U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 1st Class Mike DiMestico/Released) 181223-N-UP035-0011