For the Athenians, the Great Harbor of Syracuse was anything but. A monument to the Athenian tactic of bottle-necking of the “world’s” most powerful navy, the battle at the Great Harbor symbolizes the cost of trading mobility for convenience. Today, the five carriers lined up in Norfolk like dominoes are reminiscent of that inflexibility, serving as a greater metaphor for constraints the fiscal crisis may impose on the U.S. Navy worldwide.

– General Patton, sort of

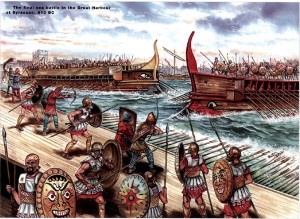

During the siege of Syracuse, the Athenian expedition anchored its naval task force inside the protected Great Harbor of Syracuse. Maintaining such a large force in a single place and at anchor decreased the costs of manning and command and control (C2). The single entrance of the harbor and its copious defenses against wind and wave also simplified the fleet’s maintenance and logistics. The convenience came at heavy cost. The fleet’s great numerical advantage was lessened by lack of mobility. Infrequent patrols allowed the Athenians to deploy navigational hazards and blockade runners. Syracuse’s superficially low-cost, reactive approach lost to the proactivity of the enemy. The harbor’s single entrance turned into a nightmare scenario as the massive fleet was locked into the harbor by a chain of ships strung across the entrance. The fleet of the mightiest naval power in the world died in a Sicilian quarry without a single ship remaining.

America’s Great Harbor is not in a foreign land, but up Thimble Shoals Channel and through the gap in the Hampton Roads beltway. Five carriers, the world’s most powerful collection of conventional naval power in one location, sit idle at harbor, one beside the other. The United States maintains a massive naval center of gravity, within a single chokepoint that could be plugged at a moment’s notice in prelude to further enemy action. The concentration not only lends itself to easy containment, but simplifies the potential for espionage and terrorism. The fiscal noose tightening around the Navy’s neck is creating a prime target that goes against every lesson we’ve learned from Pearl Harbor to Yemen.

America’s Great Harbor is a vicarious manifestation of a more terrifying fleet-wide atrophy. Sequestration will force the navy into a fiscal Great Harbor. A 55% decrease in Middle Eastern operational flights, a 100% cut in South American deployments, a 100% cut in non-BMD Mediterranean deployments, cutting all exercises, cutting all non-deployed operations unassociated with pre-deployment workups, as well as a slew of major cuts to training – these further compound the losses from the Navy’s previous evisceration of the training regime. Despite a growing trend of worries about fleet maintenance, a half year of aircraft maintenance and 23 ship availabilities will be cancelled. The snowballing impact on already suffering training and maintenance will further exacerbate that diminishing return on size and quality created by the fiscal Great Harbor. Nations like China and Iran continue to make great strides in countering a force that will recede in reach, proficiency, and awareness. The mighty U.S. Navy is forced to sit at anchor while the forces arrayed against her build a wall across the harbor mouth.

Military leadership has done a poor to terrible job advocating the true cost of defense cuts. A series of actions by the brass has undermined their credibility and covered up the problem. The blinders-on advocation for teetering problems like LCS and the F-35 have undermined the trust that military leadership either needs or can handle money for project development. The Navy personnel cuts were pushed for hard by leadership, and when the Navy grossly overshot its target, the alarms were much quieter than the advocation; the ensuing problems were left unadvertised. In general, military-wide leadership uses public affairs not to inform, but as a method to keep too positive a spin in a misguided attempt to keep the public faith. That public faith has removed vital necessary support in a time when the military is rife with problems that absolutely require funding. The PAO white-wash helps under-achieving programs and leadership get passed over by the critical eye. Where Athenian leaders were frank with their supporters at home, stubbornness and inappropriate positivity have undercut military leadership’s ability break loose from the fiscal harbor.

Those who dismiss the hazard of sequestration are wrong in the extreme. When I was an NROTC midshipman, I remember a map on the wall of the supply building: a 1988 chart of all US Navy bases around the world. Today’s relative paucity of reach leads some to believe that surviving one scaling back shows inoculation against another. However, the law of diminishing returns has a dangerous inverse. Each progressive cut becomes ever more damaging. The U.S. Navy and sequestration apologists must realize what dangerous waters the Navy is being forced to anchor in. The question is, how long can the navy safely stay in the Great Harbor before her enemies get the best of her?

Matt Hipple is a surface warfare officer in the U.S. Navy. The opinions and views expressed in this post are his alone and are presented in his personal capacity. They do not necessarily represent the views of U.S. Department of Defense or the U.S. Navy, although he wishes they did.