By Dr. Ian Ralby

The M/T MAXIMUS and the M/T ANUKET AMBER are vessels that have tested the cooperative architecture for maritime security in West and Central Africa. The MAXIMUS is considered a great success story, and the ANUKET AMBER was at least a partial success. Though each involved a different type of maritime crime, a common element between them is that they helped highlight key areas where further effort is needed to achieve the goal of collective and comprehensive maritime security in Atlantic Africa. It is vitally important to celebrate the successes that have occurred in recent years, and there are quite a few. But even in reviewing success stories there is room for teasing out lessons in how to improve. When viewed as a pair of cases, these two distinct matters help point toward how West and Central Africa can proceed to enhance maritime security in the years to come.

The Case of the M/T MAXIMUS

Relative to other piracy cases in the Gulf of Guinea, a lot has been written about the hijacking and successful recovery of the MAXIMUS. One reason for the attention is that, perhaps more than any other incident, this one demonstrated the value of the cooperative architecture set forth in the 2013 Code of Conduct Concerning the Repression of Piracy, Armed Robbery Against Ships, and Illicit Maritime Activity in West and Central Africa (Yaoundé Code of Conduct). In February 2016, the MAXIMUS was overrun by pirates about 60 nautical miles off the coast of Côte d’Ivoire. The maritime law enforcement agencies of Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana, Togo, Benin, Nigeria and São Tomé and Príncipe all cooperated in tracking the vessel across their respective Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs). Ultimately, the Nigerian Navy performed an opposed boarding, killed one pirate, captured the remainder and freed both the hostages and the vessel. At the time, the incident was heralded as the “coming of age” of navies in the region.

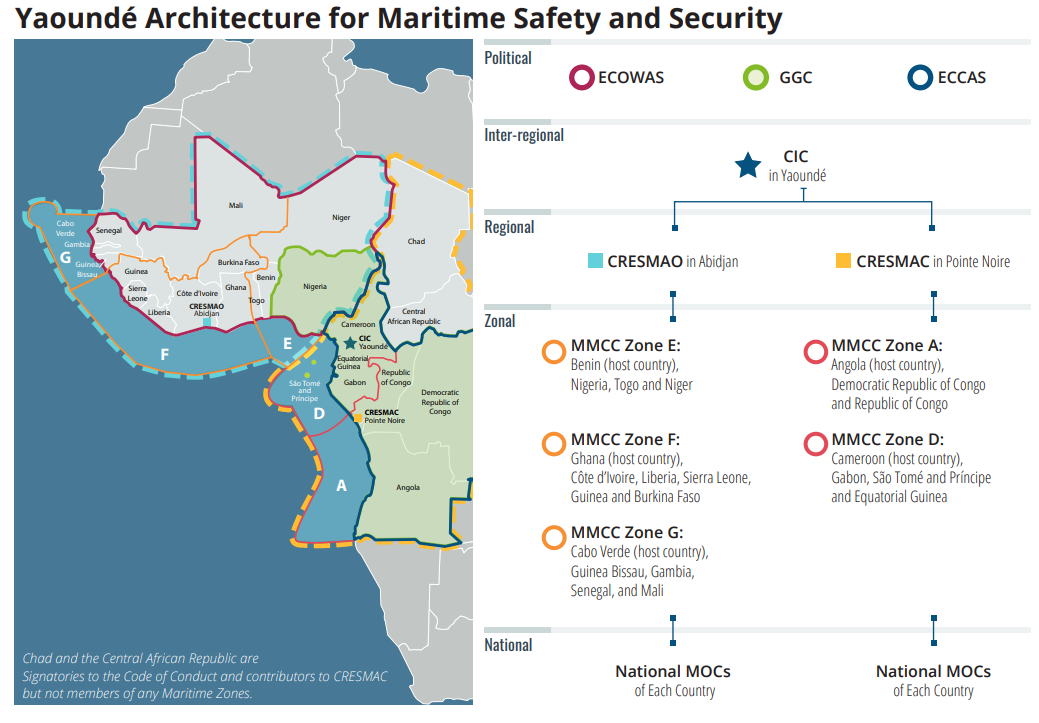

While nothing can detract from the success of the MAXIMUS case, there are some key issues that the incident revealed, several of which remain unaddressed. Perhaps the most prominent is the ongoing challenge of closing the seams between regions. The ultimate interdiction of the MAXIMUS occurred on the fault line between the Economic Community of Western African States (ECOWAS) and the Economic Community of Central African States (ECCAS), and thus on the line between the West African Maritime Security Center (CRESMAO, though not manned until 1 September of that year) and the Central African Maritime Security Center (CRESMAC), as well as between Maritime Zones E and D.

Complicating matters further, the Joint Development Zone between Nigeria and São Tomé, created by treaty in 2003, creates an overlap between those regions and zones. Theoretically, the cooperative mandate of the Yaoundé Code should resolve any tensions arising out of incidents that cross zones and regions, but the practical realities imply challenging issues of command and control. If crossing from Zone E to Zone D, should the chain be from the Nigerian maritime operations center (MOC) to the Zone E Maritime Multinational coordination center (MMCC), to CRESMAO to the Interregional Coordination Center (CIC), to CRESMAC, to the Zone D MMCC, to Cameroon or São Tomé’s MOC?

Additionally, the story of the MAXIMUS is often told as an operational success, despite, in many regards, being a legal failure. When the Nigerian Navy hailed the MAXIMUS, renamed by the pirates the M/T ELVIS 5, the pirates actually challenged the Nigerian officers, claiming they were in international waters and that the Nigerians had no legal authority to act. That baseless legal argument nevertheless slowed the Nigerians’ advance, as it caused them to take several hours to question their legal authority. Furthermore, since the case concluded, debates have continued as to why Nigerian vessels could interdict a pirated vessel in another country’s EEZ.

The legal confidence to recognize that piracy, as a matter of international law, is a crime of universal jurisdiction has been compromised by the painfully slow process of updating national legislation to even outlaw piracy. While the MAXIMUS is one of the region’s most famous piracy cases, it is not a piracy case in the court. Rather, the responsible individuals have been tried for such crimes as conspiracy, firearms violations, and mishandling of petroleum resources. While the long-awaited piracy bill in Nigeria – to outlaw the crime under national law – was finally signed by President Buhari in July 2019, it has yet to be implemented. Work has proceeded since February 2016 to build both Nigeria’s and the wider region’s legal capacity, but more work is needed.

These lessons regarding closing the seams between cooperative mechanisms and enhancing the legal wherewithal of maritime law enforcement agencies were more recently reinforced by the case of the M/T ANUKET AMBER.

The Case of the M/T ANUKET AMBER

There are actually two separate incidents involving the ANUKET AMBER tanker that occurred in the autumn of 2018 – the first has been publicized, but the second has not. On 29 October, while engaged in a ship-to-ship (STS) bunkering operation with an LNG tanker off the Republic of Congo, both the ANUKET AMBER and the ARC TZE, the vessel to which she was coupled, were pirated. In one of the only incidents of double piracy the region has seen, it took several months for the hostages to be released. In the meantime, the ANUKET AMBER itself was abandoned and recovered in Togo’s waters at the beginning of November.

The second incident, however, is the one that bears greater attention. On 17 December the Maritime Multinational Coordination Center (MMCC) for ECOWAS Zone F alerted the states of Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire that the ANUKET AMBER was engaging in systematic STS transfers in the previously disputed area of the EEZ between the two countries. On 18 December, one of the vessels with which it had rendezvoused, the MSC MARIA, actually entered the port of San Pedro in Côte d’Ivoire, where Ivorian authorities detained it. At the same time, Ghanaian and Ivorian naval operators agreed that they needed to arrest the ANUKET AMBER. While operational cooperation existed in so far as there was a good relationship between the two navies, the potential political backlash of crossing the, until recently, disputed maritime boundary rendered them hesitant.

Through activating a network of relationships with international partners and the United States government, coordinated in part by CRESMAO, both countries were able to get the political top cover needed to go and arrest the vessel. On 21 December, both navies sent vessels in pursuit of the ANUKET AMBER. Ghana’s vessel arrived first and brought her back to Tema. If the matter had ended there, this would have been a great success story in regard to the relationships of trust that have been built in the region in recent years. While Ghana later claimed that they fined the ANUKET AMBER for failure to notify them as the coastal state, they did not find the legal means to hold the vessel, and let her go on 23 December without notifying the Ivorians. That, in turn, destroyed the Ivorians’ case against the MSC MARIA, which was then let go as well.

While there are many things to celebrate about this incident – from the interaction and coordination among CRESMAO, the Zone F MMCC, and both countries involved to the immediate ability of both navies to talk with each other and reach out to international partners – this matter ultimately brought out three key issues. First was the lack of an operational memorandum of understanding (MOU) within Zone F to allow for the seamless invocation of hot pursuit, not so much as a legal matter, but as one with political implications for the two countries involved. In other words, there needed to be a standing order for them to be able to exercise the legal right of hot pursuit without fear of political backlash. Second was the lack of legal expertise to be able to at least investigate potential charges for the vessels involved. The final issue was the lack of communication between the states after the operation. While they had coordinated getting the vessels, there was no interaction when the decision was made to release the ANUKET AMBER. This suggests a need for stronger cooperative mechanisms between states during the legal finish phase of an operation.

Learning from Success

In both of these cases, the greatest success may not have been what happened on the water, but what happened in response to the shortcomings identified. On the one hand, the capacity and capability of a number of navies have improved since February 2016, suggesting the MAXIMUS case might have been resolved faster if it had happened now. Additionally, increased focus on legal understanding has improved the resilience of the navies, and new laws, like Nigeria’s long-anticipated piracy bill, serve as key tools in the fight against maritime crime. Furthermore, some of the inter-regional operational concerns that threatened the success of the MAXIMUS interdiction have been resolved. More work is likely needed to ensure smooth command and control and seamless cooperation, but there has been significant improvement in recent years.

The deficiencies recognized in the ANUKET AMBER case, however, were addressed even more swiftly and aggressively. Even during the incident, notes were being taken as to what needed to be improved. In early 2019, Côte d’Ivoire held a national debriefing on the matter and, recognizing the need for stronger laws, began work on improving its legislation regarding STS transfers.

Thereafter a multilateral debriefing involving all the parties – Ghana, Côte d’Ivoire, MMCC Zone F and CRESMAO – on 25 February 2019 identified the key takeaways from the experience. First and foremost was developing an operational MOU for MMCC Zone F to avoid encountering some of the same operational challenges as the states had in December. The speed with which this was addressed – exactly five months after that meeting – is a tremendous credit to the drive of the states involved as well as to the leadership of both the MMCC Zone F and CRESMAO. The MOU was largely drafted in March 2019 and subsequently signed on 25 July.

Lessons on the Horizon

In the spirit of continual improvement, it is worth noting that these structures of security cooperation under the Yaoundé Architecture are going to be challenged time and time again. Notwithstanding the spike in piracy in and around Nigeria, there are plenty of other transnational maritime threats that will likely help to both validate and further refine the architecture. For example, fishing vessels registered in one state that are fishing in the EEZ of a nearby state and then dragging nets on the way home across a third state, or complex networks of offshore transshipments, are the sorts of scenarios that are not yet fully capturing the attention of maritime law enforcement agencies but will likely become a key test of the cooperative mechanisms in the months and years to come. That said, the prompt response of the region to incorporate lessons learned provides cause for optimism that the Yaoundé Architecture will be able to adapt to threats as it matures. While learning from failure is often a necessity, these cases involved learning from what were otherwise important successes, and that is truly something to celebrate.

Dr. Ian Ralby is a recognized expert in maritime law and security and serves as CEO of I.R. Consilium, a family business with leading expertise in maritime and resource security. He is also a Maritime Crime Expert for UNODC’s Global Maritime Crime Program and a Senior Fellow at the Atlantic Council. He previously spent four years as Adjunct Professor of Maritime Law and Security at the United States Department of Defense’s Africa Center for Strategic Studies.

Featured Image: Arrested pirates who hijacked the MT Maximus last month. (Sunday Alamba/AP)