By Joshua Tallis

“Maritime security.” The phrase, and the nebulous set of missions that loosely fall underneath it, came into expanded use in the decades after September 11, including in U.S. strategic documents. Even during the height of interest in maritime security, however—say, around 2007 and the publication of A Cooperative Strategy for 21st Century Seapower—it was not clear how those missions could or should be prioritized with respect to other strategic challenges. As the Department of Defense, and the Navy with it, reorients to great power competition, it will only become easier for those questions to slide into the background. And yet, as we will see below, historical trends and emerging patterns will conspire to keep the littorals at the forefront of policymaker’s minds. Alongside the renewed focus on traditional adversaries, therefore, operations in green and brown waters driven by unconventional threats will likely play an enduring role in U.S. foreign policy.

In his book Out of the Mountains, counterinsurgency strategist David Kilcullen sets out a compelling argument for taking the littorals seriously. Kilcullen’s argument is focused on events ashore, but his articulation of the global drivers shaping the littorals can be made equally valuable for the seaward end of the domain. The premise underlying these drivers is based on one simple principle: conflict happens where people are.1 So, where are the people?

In response, Kilcullen identifies four “megatrends” of demography and economic geography that suggest where we will find most of the world’s population in the coming decades. “Rapid population growth, accelerating urbanization, littoralization (the tendency for things to cluster on the coastlines), and increasing connectedness” all suggest that populations are concentrating in networked, urban, dense, littoral communities.2 UN estimates project that by 2050 at least two-thirds of the global population (which is projected to reach 9.8 billion) will likely live in cities, a great many of whom will end up in slums (where about a billion people already call home). Moreover, much of this urban expansion—most of which will be coastal—will take place across the global South, often where governments are least prepared to receive it. The populations of the Caribbean and Latin America could grow by more than 130 million people; Africa may see its population expand by more than a billion; and Asia will see a growth of at least 800 million according to mean estimates from the United Nations.

To give an indication of scale, consider the following. In one generation, the world’s poorest cities will absorb most of a population increase equal to all the population growth ever recorded in human history through the year 1960.3 That is sure to produce astounding institutional strains, ones that will inevitably stress already fragile municipal governments. And we need not wait for 2050 to see these statistics in action. Today, half of the world’s population lives within about thirty miles of a coast, and three-quarters of large cities are on the water. To those and other cities, nearly 1.5 million people migrate to every week, which explains why urban areas are soon expected to absorb almost all new population growth.4

But how is demography dangerous? The answer comes from how urban communities respond to the pressures of these trends. Research suggests that when a city doubles in size, it produces, on average, “fifteen percent higher wages, fifteen percent more fancy restaurants, but also fifteen percent more [HIV/AIDS] cases, and fifteen percent more violent crime. Everything scales up by fifteen percent when you double the size.”5 In cities already straining their respective systems, cities like Lagos or Mumbai or San Pedro Sula, the consequences of a 15 percent spike in crime or HIV/AIDS rates act on preexisting stressors like poverty, climate change, and political violence, which can precipitate disorder. In the most extreme cases, the impact of these magnified stressors might even cause a metropolis to turn “feral.” In the Naval War College Review, Richard Norton defines a feral city as “a metropolis with a population of more than a million people in a state the government of which has lost the ability to maintain the rule of law within the city’s boundaries yet remains a functioning actor in the greater international system.”6 John Sullivan and Adam Elkus describe the feral city as a place without any meaningful presence of legitimate authority, where “the architecture consists entirely of slums, and power is a complex process negotiated through violence by differing factions.”7 Norton noted at the time that only Mogadishu truly exemplified his criteria of a feral city. Yet, several cities then contained feral pockets characteristic of Norton’s theory. In such pockets, segments of an urban sprawl may exist outside the reach of the government. A Proceedings article by Matthew Frick as well as a New York Times piece both cite São Paulo, Mexico City, and Johannesburg (the Times also adds Karachi) as examples of modern cities with components that could be described as feral.8 Frick even explicitly links these feral cities to maritime security by arguing that they are echoes of the pirate havens of the 18th century, when raiders similarly leverage ungoverned spaces as bases of operation. In feral cities or pockets, the legitimate governing fabric of the urban area erodes as the stress of an oversized population pushes it past the ability to cope with the pressures of crime, poverty, and health. Such violence perpetuates the cycle of urban exclusion that created it, precipitating yet more political, social, economic, and infrastructure neglect.9

The collapse or erosion of local governance creates a power and services vacuum. That power vacuum creates disorder from which people naturally crave a reprieve. In turn, the local actor that can produce a sense of order and stability is frequently adopted as a surrogate government. Inevitably, these surrogates are not peaceful neighborhood watch groups. Kilcullen’s concept of “competitive control” posits that the surrogates most likely to survive in these environments are those that can act across a spectrum of power ranging from soft to coercive.10 Without soft power, the allure of an institutionalized set of normative community rules, the population is denied the sense of order it demands. Under such a rules-based system, a neighborhood is likely to tolerate a measure of violence because it can be predicted and avoided. Without violence, a competitor will find it easy to supplant the surrogate. What we are left with is a void filled by organized gangs, terrorists, militias, or criminal networks that manipulate a feral city’s disorder to establish fortifications within neighborhoods that often come to depend on them. In Kingston, Jamaica, garrison neighborhoods offer one such example where these districts are made loyal to gang leaders because of their dominant role in the local informal justice system and economy.11 We are left facing an amorphous hybrid threat, what John Sullivan calls “criminal insurgents,” or the melding of criminal syndicates with the direct political control of territory.12 When such groups offer residents enough of a sense of fair and predictable order, many are willing to tolerate their presence.

So far, however, violent nonstate groups and feral cities would appear a danger largely within their own neighborhoods, far from concerning the United States, and certainly not U.S. maritime services. What brings these groups and populations into the international maritime orbit is Kilcullen’s final megatrend—connectedness. Crowded, poor, coastal zones may turn feral, but feral regions do not implode. Instead, they remain connected with the world around them through the Internet, ports, airports, diaspora communities, and other connective tissues. Thus, with all the implications of such connectedness, even a feral region remains a dynamic, strategic, and significant actor in the international arena. This connectedness allows the feral elements of a community to interact with licit and illicit trade and information flows, offering local actors the capacity to directly impact events across the country and, potentially, the globe.13 The same pathways that facilitate normal trade and migration likewise enable illicit transfers such as the smuggling of narcotics, people, and weapons; human trafficking; terrorism; and piracy. This connectedness is what gives rise to the potential for actions a world away, events like protests or acts of political violence, to have a rapid and meaningful consequence across domains, from cyberspace to the sea. September 11 was a dramatic example of the extreme consequences of this networked, globalized connectivity of local violence to the international system. What we have increasingly seen in the intervening two decades, thanks in part to the explosive growth in technologies that connect all of us, is that this ladder between local and international is only strengthening. As a result, in the sphere of nonstate threats, “the distinction between war and crime, between domestic and international affairs” almost disappears.14

As the line blurs between war and crime, the capacity for the return to great power competition to focus minds on a singular, important challenge may simultaneously make it more attractive for strategists to circumvent planning for these opaque, nontraditional challenges. History, however, suggests that would be a mistake. What is remarkable about the pattern of unconventional conflict is its irreverence for the preferences of policymakers.15 Lyndon Johnson was eventually subsumed by a troop escalation in Vietnam despite his clear domestic policy agenda. Bill Clinton, after reluctance to act in the Balkans and Rwanda, ultimately sent troops to Bosnia, Kosovo, Macedonia, Haiti, and Liberia. While candidate George W. Bush dismissed interest in stability operations, President Bush launched two prolonged, large-scale counterinsurgency campaigns and led NATO into its largest stabilization mission ever.16 As President Obama initiated his pivot to Asia, he was still negotiating the drawdown of two land wars while conflicts simmered (and flared), inter alia, in Syria, Yemen, Somalia, Iraq, Mali, Nigeria, and the Congo. Now President Trump, despite obvious isolationist impulses, has struggled to extricate U.S. forces from Afghanistan and Syria in practice. “American policy makers clearly don’t like irregular operations, and the U.S. military isn’t much interested in them, either,” but as the demographic and economic geographic trends discussed above suggest, they will likely continue to present policymakers with difficult choices.17

Any attempt to predict the exact nature of a future threat or conflict is a fool’s errand. To borrow a metaphor from Kilcullen, much like how climate modeling cannot say whether it will rain or snow next week, the projections above say little about the near-term conflict forecast. Yet, just as with climate models, such forecasts “do suggest a range of conditions—a set of system parameters, or a ‘conflict climate’—within which [future] wars will arise.”18

These projections illustrate trends. And while those trends do not say much about what happens tomorrow or the day after, they speak volumes about the forces steadily reshaping our world. These forecasts are unequivocally telling us that dense, networked, and littoral communities are an emerging global force. How maritime forces meet (or fail to meet) the challenges associated with that rise will be dictated by their attentiveness to the unique constraints of securing muddy waters.

Joshua Tallis is the author of The War for Muddy Waters: Pirates, Terrorists, Traffickers, and Maritime Insecurity, from which the above passage is adapted. He is a research scientist at the Center for Naval Analyses and holds a PhD in international relations from the University of St Andrews.

References

[1] David Kilcullen, Out of the Mountains: The Coming Age of the Urban Guerrilla (London: Hurst, 2013), 239.

[2] Ibid., 25.

[3] Ibid., 29.

[4] Ibid., 29.

[5] Ibid., 247.

[6] Richard Norton, “Feral Cities,” Naval War College Review 56, no. 4 (2003): 98.

[7] John Sullivan and Adam Elkus, “Postcard from Mumbai: Modern Urban Siege,” Small Wars Journal, February 16, 2009, 8.

[9] Kilcullen, Out of the Mountains, 40.

[10] Ibid., 114.

[11] Ibid., 89, 93.

[12] Sullivan and Elkus, “Postcard from Mumbai.”

[13] Kilcullen, 45.

[14] Ibid., 99.

[15] Ibid., 24.

[16] Ibid., 24.

[17] Ibid., 24.

[18] Ibid., 27.

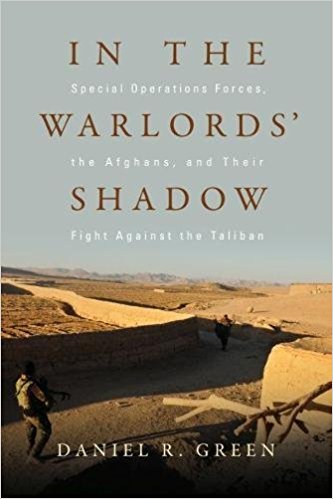

Featured Image: A Republic of Singapore Navy Littoral Mission Vessel (background, far left), and the Police Coast Guard’s patrol interdiction boat (at right) intercepting a mock terrorists’ speedboat in Singapore waters off Changi Coast Road during a demonstration for Exercise Highcrest. (PHOTO: LIANHE ZAOBAO)