By Victoria Castleberry

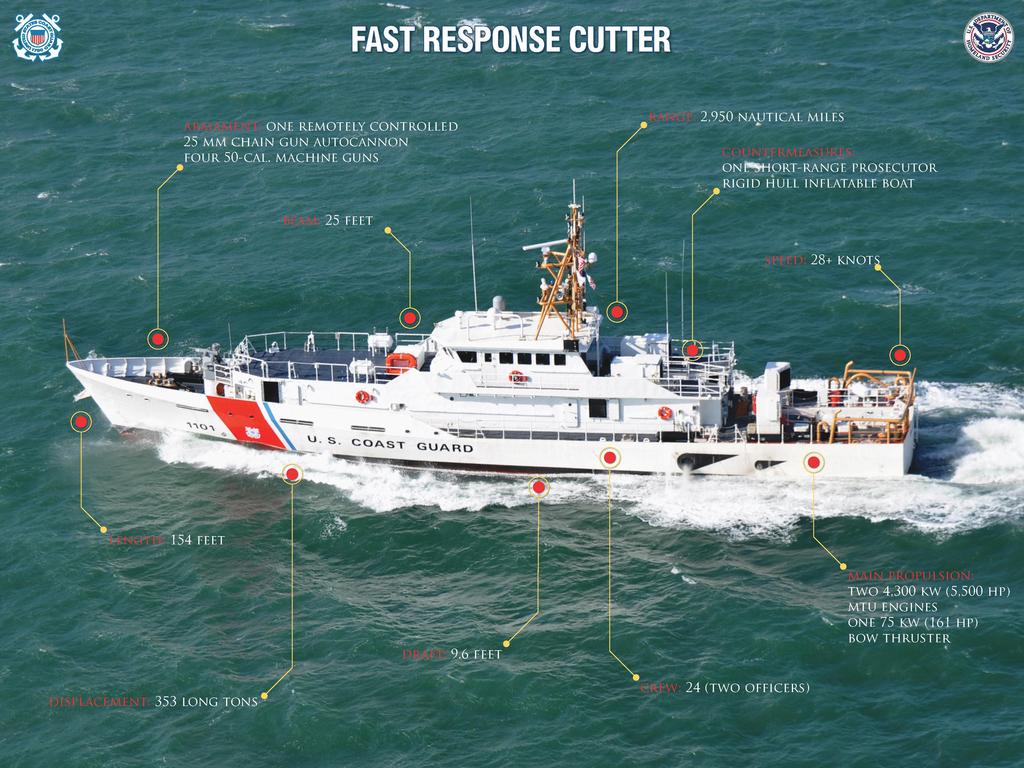

The need for security of international maritime trade has never been greater as over 90 percent of internationally traded goods are transported via maritime shipping and 70 percent of maritime shipped goods are containerized cargo.1 Most trade vessels are funneled through one or more of six strategic chokepoints around the world: the Suez and Panama Canals, Strait of Malacca, Strait of Bab el-Mandeb, Strait of Gibraltar, and the Strait of Hormuz.2 Perhaps the most unique of these chokepoints is the Strait of Hormuz, and the presence of six 110’ Coast Guard Cutters in its vicinity. Coast Guard presence provides what no other U.S. asset can to this hostile region: provide security without an escalation of arms and the facilitation of transnational cooperation through various interagency programs. Expanding this model of strategic deterrence by increasing the U.S. Coast Guard’s presence internationally, the United States will be capable of protecting our most precious passages, promote international cooperation, and give the U.S. an advantage in determining how the international maritime waterways are governed.

According to the Energy Information Administration, the Strait of Hormuz exports approximately 20 percent of the global oil market and a total of 35 percent of all sea-based trade.3 With such a valuable resource transported through a small area, the necessity of security for this strait is clearly essential to the international market. Unfortunately, tensions within the region are rising and the risk of port closure, piracy, and military interference are all real possibilities that the global market may face when transporting through this region.4 In an effort to counter potential mishaps the United States has already utilized the Coast Guard to provide an authoritative yet non-threatening presence in the Persian Gulf that over time has proven effective.

Currently the Coast Guard spearheads several programs in Patrol Forces Southwest Asia (PATFORCESWA).5 Programs in the region specialize in the training of Coast Guards from around the world to bolster international maritime security cooperation. These programs help to support Article 43 of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) agreement which requires user and bordering states to cooperate for the necessity of navigation and safety for vessels transiting.6 This specific call to duty for the user and bordering states by UNCLOS is a mission set specialized by the Coast Guard. The Coast Guard is currently operating in Freedom of Navigation Operations, escorting of military vessels, hosts an International Port Security Liaison Officer program, and possesses a Middle East Training Team responsible for conducting operations in conjunction with foreign militaries.7

As previously stated, the Coast Guard currently offers programs which work toward international cooperation for maritime security. Programs offered in the Persian Gulf include the International Port Security Liaison Officer (IPSLO) program and the Middle East Training Team (METT). These programs act as partnerships between the U.S. Coast Guard and foreign militaries to build up and sustain their own Coast Guards, as well as improve their own port security to facilitate trade between all nations.8 The IPSLO program allows for a “sound foundation from which countries can build their own domestic maritime security system.” This foundation is built through the education and enforcement of the international codes.9 Other programs such as the METT regularly participate in “theater security cooperation engagements with foreign navies and coast guards throughout the region.” These teams focus on teaching other coast guards and navies proper procedure for LE boarding and smuggling interception.10 These are the programs which need support to protect maritime chokepoints globally.

Lieutenant Jared Korn, USCG, was the Operations Officer aboard USCGC Adak, one of the six cutters deployed to PATFORCESWA. When asked about situations experienced while deployed within the Persian Gulf region, LT Korn described instances where Iranian vessels would approach the cutter and eventually depart. LT Korn to explained that in whole, the U.S. Coast Guard is an internationally recognizable symbol for aid, security, and is notably less threatening than a grey-hulled naval vessel within the Persian Gulf region.11

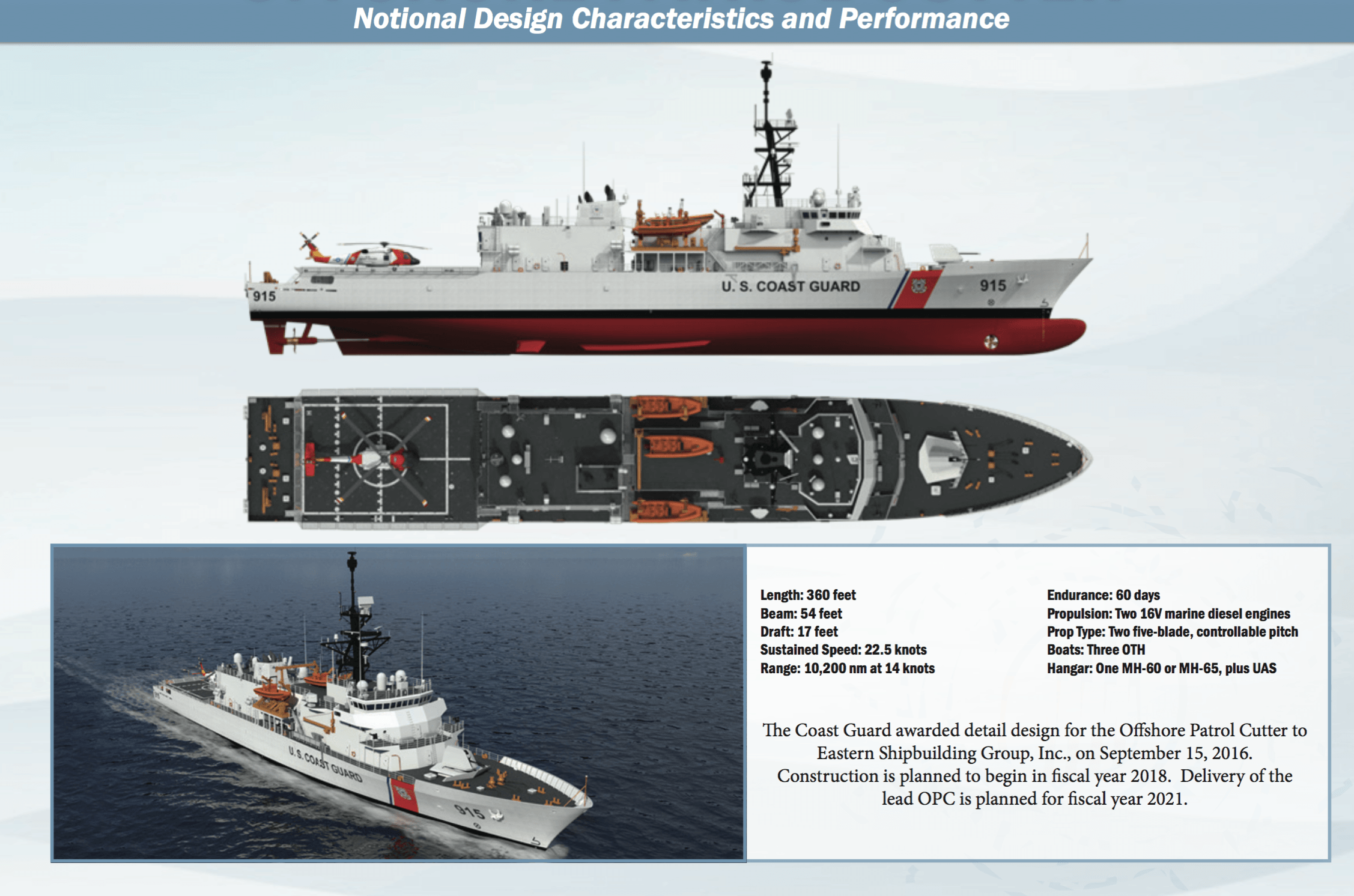

The presence of the U.S. Coast Guard in the Persian Gulf has been an effective tool in deterrence of hostiles within the region. This model can and should be applied to the other strategic chokepoints around the world. In 2014 the Panama Canal was faced with 44 reported piracy attacks, the Suez Canal is similarly plagued with piracy, off the coast of Somalia pirates have collected ransoms for over 10,000 dollars.12 Other strategic chokepoints such as the Strait of Gibraltar, Strait of Malacca, and Strait of Bab el-Mandeb would also benefit from the presence of the U.S. Coast Guard within their regions. Although these regions are not experiencing as severe of a threat to their maritime trade route imminently, prevention-based presence could avoid severe consequences of trade shutdown in these strategic chokepoints. The best way to do this is to grow the U.S. Coast Guard’s patrol craft fleet internationally as well as the training programs which aid in the diplomatic relations and sovereignty of nations’ security.

Although the solution of expanding the Coast Guard’s mission internationally is possible, it does have two potential obstacles. The first obstacle is public perception, the second, asset availability. Public perception of law enforcement today is already at an all-time low. By allowing our only armed service with law enforcement capabilities to shift its mission internationally the United States runs the risk of the American people’s perceptions shifting as well.13 The positive perception by the American people of the Coast Guard is at risk of being diminished due to the perception of war-like actions by our domestic maritime law enforcement. More clearly, however, is the logistics. As the smallest branch of the armed services the U.S. Coast Guard accomplishes its mission set with just a fraction of the assets, personnel, and budget as her Department of Defense counterparts. Expanding the mission set of the Coast Guard will only spread these resources more thin without congressional budgetary aid to gradually build up international forces overseas.

The solution to the problem of securing strategic maritime passageways is a complex one. The solution cannot escalate tensions, must facilitate international cooperation, be non-intrusive, and help bolster nations’ forces. In many of the strategic chokepoints around the world, tensions run high. The necessity for diplomatic operations makes the Coast Guard the best choice to accomplish this mission. Expanding the United States Coast Guard’s assets and programs internationally will allow for these requirements to be met and give the United States a strategic advantage in the control of international maritime security.

Victoria Castleberry is a student at the Coast Guard Academy. She is a junior who studies government and focuses on security studies. She is the varsity coxswain for the women’s crew team. She participates in the cadet musical and was recently a dancer in the musical Footloose. She has 2 dogs named Ezekiel (Zeke) and McCain (Mac) and grew up in Northern Virginia. She will be stationed in Puerto Rico on the USCGC Richard Dixon this summer. She hopes to become a Deck Watch Officer and drive big white boats somewhere south of the Mason-Dixon Line and attend law school.

Bibliography

Allen, Craig, Jr. “White Hulls Must Prepare for Grey Zone Challenges.” U.S. Naval Institute, November 2016: 365.

Castonguay, James. “International Shipping: Globalization in Crisis.” Witness Magizine. n.d. http://www.visionproject.org/images/img_magazine/pdfs/international_shipping.pdf (accessed March 28, 2017).

Katzman, Kenneth, Neelesh Nerurkar, Ronald O’Rourke, R. Chuck Mason, and Michael Ratner. “Iran’s Threat to the Strait of Hormuz.” Congressional Research Service, 2012: 1-23.

Korn, LT Jared, interview by Victoria Castleberry. Operations Officer CGC Adak Interview (March 29, 2017).

Rodrigue, Jean-Paul. “Stragetic Maritime Passages.” The Geography of Transport Systems. n.d. https://people.hofstra.edu/geotrans/eng/ch1en/appl1en/table_chokepoints_challenges.htm (accessed March 27, 2017).

US Coast Guard. United States Coast Guard. December 12, 2016. https://www.uscg.mil/lantarea/PATFORSWA/ (accessed March 30, 2017).

—. United States Coast Guard. December 21, 2016. https://www.uscg.mil/d14/feact/Maritime_Security.asp (accessed March 31, 2017).

Williams, Colonel Robin L. Somalia Piracy: Challenges and Solutions. Academic Reseach Project, Carlisle Barraks: United States Army War College, 2013.

1. Castonguay, James. “International Shipping: Globalization in Crisis.” Witness Magizine. n.d. http://www.visionproject.org/images/img_magazine/pdfs/international_shipping.pdf (accessed March 28, 2017).

2. Rodrigue, Jean-Paul. “Stragetic Maritime Passages.” The Geography of Transport Systems. n.d. https://people.hofstra.edu/geotrans/eng/ch1en/appl1en/table_chokepoints_challenges.htm (accessed March 27, 2017).

3. Katzman, Kenneth, Neelesh Nerurkar, Ronald O’Rourke, R. Chuck Mason, and Michael Ratner. “Iran’s Threat to the Strait of Hormuz.” Congressional Research Service, 2012: 1-23.

4. ibid.

5. US Coast Guard. United States Coast Guard. December 12, 2016. https://www.uscg.mil/lantarea/PATFORSWA/ (accessed March 30, 2017).

6. United Nations. United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, § Part III Straits Used for International Navigation (n.d.).

7. US Coast Guard. United States Coast Guard. December 12, 2016. _______https://www.uscg.mil/lantarea/PATFORSWA/ (accessed March 30, 2017).

-United States Coast Guard. December 21, 2016. https://www.uscg.mil/d14/feact/Maritime_Security.asp (accessed March 31, 2017).

8. United States Coast Guard. Maritime Security

9. United States Coast Guard. Maritime Security

10. ibid.

11. ibid.

12. Williams, Colonel Robin L. Somalia Piracy: Challenges and Solutions. Academic Reseach Project, Carlisle Barraks: United States Army War College, 2013.

Featured Image: ASTORIA, Ore. – Two Coast Guard 47-foot motor lifeboat crews comprised of members from smallboat stations throughout the Thirteenth District train in the surf at Umpqua River near Winchester Bay, Ore. (Coast Guard photo by Petty Officer First Class Shawn Eggert)