By Matthew Merighi

Join us for the latest episode of Sea Control for a conversation with Bill Harlow, an author and former intelligence community spokesman, about his work in strategic communications in the armed forces. He talks about the public affairs career track in the military, his experience at all levels of government, and how that experience informs the civilian work he does today.

Download Sea Control 145 – Strategic Communications with Bill Harlow

A transcript of the interview between Bill Harlow (BH) and Matthew Merighi (MM) is below. The transcript has been edited for clarity. Special thanks to Associate Producer Cris Lee for producing this episode and writing the transcription.

MM: Now, as is Sea Control tradition, please introduce yourself. Tell us a little bit about your professional background, what you’re up to now, and how you got from where you started in your career to where you are at the moment.

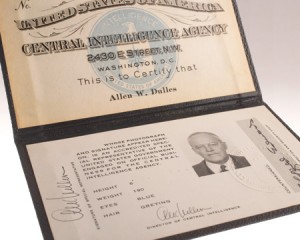

BH: Well, I like to think of myself as a communications professional. I started out in the Navy, got a commission through ROTC from Villanova. And spent 25 fascinating years in the Navy, most of that as a public affairs professional. I had a number of very interesting tours while on active duty, including four years at the White House Press Office, and duty at the Pentagon many times in various spokesman positions. This included Chief Spokesman for the secretary of the Navy and retired as a Navy Captain in 1997, and went to work as chief spokesman for a secret organization. Sounds like it should be a pretty easy job.

Then I was the spokesman for the CIA for 7 years, from 1997 to 2004. I left that job and did a couple things, one was writing and helping various people, mostly former CIA officials, write their memoirs or books. I do that under my Bill Harlow communications hat. Then I also started a company called 15 Seconds, 15-seconds.com, with Fred Francis, a former NBC news correspondent. We do crisis communications and media training, and tell clients how to approach dealing with the media from the dual perspective of Fred who spent 40 years in network news and my perspective of spending almost that much time as a government spokesman, so it provides a unique perspective to people about how to deal with the media in the current environment.

MM: Well, that’s a very broad and diverse set of career experiences so what we’ll do is start from the beginning. As you can imagine, as our listeners already know, most of the people we have come through military backgrounds on Sea Control end up talking about more kinetic topics and have line officer backgrounds but you ended up in public affairs. What made you want to go down the public affairs route and how did you end up getting involved in that world?

BH: Well, I always had an interest in communications and media relations and those kind of things, but I owed the Navy four years of service for my ROTC scholarship and fortunately after a couple quicks and takes I ended up aboard USS Midway as the collateral duty public affairs officer. I got on board in Alameda and about three days later the ship got underway for Japan for a cruise that lasted a couple generations, but I was fortunate enough to be on board when the Midway went to Yokosuka for the first time. And while on board I was able to run the ship’s newspaper, the closed-circuit radio TV. It also involved dealing with crises that we had on board, things like that, while also standing bridge watches from time to time.

And although I eventually qualified as an Officer of the Deck underway on the Midway, I was having more fun doing the communicating part of it than driving the ship. So, at the end of my tour there I applied for conversion to the public affairs designator within the Navy. It’s a very small community within the Navy, Public Affairs specialists who do that solely for the rest of their careers, and I was fortunate enough to be selected. When I went ashore from the Midway, I was able to build on what I learned in the fleet to help the story of the Navy for the next twenty-plus years.

MM: I want to ask a more general question in terms of what then is the traditional glide path and the traditional trajectory for a person that is doing public affairs in either the Navy or the military services? What kind of assignments do you normally end up getting, what are the standard kind of cycles that you go through to get into those positions, and how exactly does a public affairs career end up unfolding?

BH: It varies widely and it certainly varies more widely when you talk about the different services. The Navy I think has the best track record of training and deploying their spokespeople. They give them a lot of responsibility early on, which is typical of the Navy in general as you know. And they tend to put their spokespeople in areas of fleet concentration, whether its Norfolk or San Diego or whatever. Or places where there’s lots of communications opportunities like the Pentagon and again there’s only a small number of people. When I was in less than two hundred, total. The seniormost person was usually a one star, and then on down to the junior-most person, they might be a JG or a LT. And so they’re spread pretty thinly but you get an opportunity to deal with both media relations and with the press, along with internal relations communicating within the Navy whether it’s through closed-circuit TV or through other broadcasts or internet platforms now. It also includes community relations and dealing with the public, trying to get the public to understand what the Navy does and why it does it and try to build support that can be anything from working with the bands or with the Blue Angels, to all manner of things. So those are the kind of jobs that you end up getting within the public affairs community.

MM: You had some pretty high profile and high visibility positions. So, let’s talk a little bit about your time at the White House. I’m looking at your bio and seeing the years. You were there right during the transition between President Reagan and President Herbert Walker Bush, which was obviously an interesting time for national politics and international affairs with the collapse of the Soviet Union, the establishment of the new world order, complete redefinition of the world as we knew it. Which means that as things are changing quickly, I’m sure it was very, to put it mildly, interesting to say nothing of difficult to keep abreast of those changes and communicate what the White House was doing and what the world was becoming. So, tell us a little bit about what your time was like in the White House, particularly the transitions between the two presidencies and the transition in world order.

BH: Yeah, it was a fascinating time to be there. I guess it’s probably any time that the White House is fascinating, but it certainly seemed to be that I was fortunate at that particular time and it wasn’t meant to be as long as it turned out to be. At the end of the Reagan administration there was a vacancy at the White House press office in the part that handled national security. They reorganized several times back and forth, but that particular spot would be assigned to the National Security Council staff, but at the time we were considered White House staff. And there was a vacancy at the end of the Reagan administration and there weren’t any civilians beating down the door to take the job because there were only a few months left in the administration. So people didn’t want to leave a paying job to go there. So, people at the White House thought well maybe we can get a military guy to fill in for the final nine months of the Reagan administration. And they called over to the senior spokesman for the Pentagon and they asked if he knew anybody that would fit the bill, and at the time I was the senior military assistant to the assistant secretary of defense for public affairs and he asked me for a recommendation and I said, “How about me?” And he kindly said, “Sure go over and interview,” and I went over and interviewed. I was fortunate enough to be selected for what I thought was going to be a nine-month job. But then when President George Herbert Walker Bush won election, he asked the Presidential Press Secretary Marlin Fitzwater under President Reagan to stick around and keep that same job in the new administration and Marlin was kind enough to ask me if I would like to stay for a little bit longer. And I said, “heck yes.” So I took what was a nine-month temporary assignment and milked it for about four years.

It was a remarkable time to be there. President Reagan was a fascinating, wonderful guy to be around. You knew you were in the presence of somebody who was really powerful but also like your favorite uncle. You couldn’t help but like the guy if you were around him a little bit. He was truly a great communicator and he spent a lot of time working on his communications. And so, for a public affairs guy, that was a wonderful thing to observe and to play a small part in. I was there. And toward the end of his administration when he went to Moscow, for the summit meeting and things like that, I traveled with the president a little bit. It just was was a fascinating time.

Then the Vice President George Herbert Walker Bush becomes president, and it was a remarkable period in history. The fall of the Berlin Wall, the first Gulf War, the Soviet Union coming apart. And again, I was privileged to have been able to travel with him around the world, to a number of events and to be there taking part in figuring out how do we deal with these crises and how do you respond to a situation like the Berlin Wall coming down.

I think President Bush doesn’t get nearly enough credit for the way he handled all those things masterfully. He could’ve said or done things that would’ve triggered a negative response from the Soviet Union, but he handled it just perfectly and in a way which allowed the Soviet Union to take itself apart without taking down large portions of the West with them. So, it was a wonderful opportunity, working at the White House is of course a privilege.

One thing I would say is different about working in the White House and working in the military is that almost everyone at the White House understood the importance of communications. And so, you never had a problem getting the attention of some senior official to get them to give you information that you could use to respond to the media, to talk to them and think through the implications of how the reactions would play out in the media. Sometimes in the military, you run into senior officials who think “my job is to be a warfighter and that’s all I care about,” and that “The public doesn’t have to know anything about what we’re doing and therefore you press guys stay out of the way.” That was not the situation in the White House for they understood by the very nature of their jobs that they had to communicate effectively in order to do a good job for the administration and for the country.

MM: And so… when you’re within the White House versus in the military there’s a difference between how the senior leaders view the need for communications. What about the battle rhythm, sort of the day-to-day work. Was it fundamentally the same between those two organizations even though the leadership put a different emphasis on strategic communications, or is the nature of doing public affairs the same regardless of whether you’re on the civilian White House side or the more military DoD side?

BH: I think it’s close to the same, I brought with me sort of a military ethic when I got to the White House. I made a point of getting in an hour ahead of my boss, which is a typical military thing when you’re an aide or a military assistant or something like that. And just immersing myself with the information to try to stay ahead of the game because there was so much information coming in since there are so many things you need to anticipate and deal with. And like in any organization, you just never know what’s going to come at you, there’s so many possibilities that you need to stay on top of things. The last thing you want at the White House or at any senior military command is to be surprised by actions that there’s any way to know of. You want to stay ahead of the curve but it was challenging, and it’s even more so today given the plethora of media outlets that are there to deal with so it must be even harder to stay ahead of the game.

MM: So that what it’s like on the civilian or the government civilian side and on the military side. So let’s talk about the third leg of that stool which is secret organizations. So, you went to work for the CIA in 1997?

BH: That’s correct, yes.

MM: So, in 1997, you joined the CIA as a communications person, as chief spokesman. You held that position for a number of years. So, tell us then what was the difference working on the intelligence side, as you mentioned what is it like to be in charge of the responsible for the communications or the organization whose primary cultural aspect is to try to give away as little as information as possible

BH: Yeah, it was certainly challenging. And I thought going into it I would have a little bit of a leg up on it because I had worked with the military and from time to time worked with the Navy submarine community, for example, which is notably tight-lipped and with the special warfare communities and things like that. CIA takes it obviously to a completely different level. And there are a large number of people within the organization who will forever think that the only response to any question should be “no comment.” And then they would be just as happy if the press job didn’t exist. But my argument and the argument which my boss Director George Tenet fully endorsed was that the agency has a responsibility to talk about what it can so that in those occasions when it must be secret, it has some credibility. When you say everything in the world is classified, everything is to be responded with “no comment,” but then you have no standing if the media come to you and they haven’t learned something secretive and you ask them “please don’t report that” because it would do damage to national security. You have no standing if you have been telling the same thing all along for every simple question that they might ask.

It’s also an opportunity, because of the nature of the organization, there are things that the intelligence community does that can be talked about. There’s analysis they do that is quite valuable to the public and the private sector, there are actions taken that can be spoken about and if you put some deposits in the credibility bag, they will be able to describe a few of the success against the inevitable stories that get out there about the failures the intelligence community or about the other difficult enemies you run into. You’ve got more ability to offset that if you play the game. If you totally stiff the media, totally refuse to respond to any question, when stuff goes badly, and it will, inevitably you’ve got little leg to stand on when they try to put it in perspective.

MM: So, let’s talk then about some of the specific events that happened while you were at the CIA because you were there for a number of years and I’d say the two that sort of pop up are 9/11 and the prosecution of the Iraq War. So, I was wondering if you could walk through then some of the specifics that you actually can talk about in your role. What it was like to be there during that tumultuous time and that very difficult time for our country?

BH: Yeah, again it was a fascinating time to be where I happened to be. The CIA was the one part of the government that was most alarmed about the potential threat from al-Qaida for a number of years. When I first got there in 1997, it was very worried about it, working aggressively against that target, but it was a very difficult one to get attention to. If you go back and look at the public testimony that the Director of Central Intelligence George Tenet made in 1998-99-2000 even early 2001, he was saying things along the lines of, “al-Qaida could attack any moment without further notice.” So, we were trying to get the word out that this was a serious situation of extraordinary concern to the agency and to the nation, but again you run into the difficulties of not being able to talk about many of the things you are doing, and also there’s so much that’s unknown about it. But we were definitely feeling the potential pressure of that situation as the 9/11 commission quotes that Director Tenet was saying that at the time the system was blinking red and we knew that something big was coming. We didn’t know precisely where, we didn’t know precisely when, we didn’t know how it would happen. We were trying to raise the alarm within government but there’s always only so much you can do there, because if you can’t tell them precisely what’s going to happen or where, they say to you, “aren’t you guys just crying wolf again?”

So, there was a tremendous feeling of pressure at the time and then when 9/11 happened. I was at the CIA headquarters that morning and we were in a senior staff meeting and one of the watch officers came in to the director’s conference room and said a plane has just hit the World Trade Center. And while many people will say their initial reaction was “it’s probably a small plane that got lost or something,” I think our reaction was generally was it could well be al-Qaida and I went back to my office and saw the second plane and then certainly knew instantly that it was. Then there was the tremendous outpouring and support where the entire country came together to try to band together against this fight. And the wonderful work that was done by the agency and special warfare community in going into Afghanistan after a couple weeks of 9/11 and essentially routing the Taliban and putting al-Qaida on the run was a very dramatic period in the country’s history.

And then what inevitably happens after a crisis like that, the first reaction is that people pull together and work together and the second reaction is that people start pointing fingers. “Why didn’t somebody tell us? Why didn’t you stop this? Why didn’t you do whatever it is in retrospect what should’ve been done?” And after the crisis whether it’s that one or whether its any other one you could name, it’s very easy to go back and look at things that might have been done, should have been done. You now have the complete picture and you go back and find the pieces of the puzzles that were missing. At the time when you’re in the run-up to a crisis, the cliché is that it’s like having a jigsaw puzzle without the box top, or worse than that is a jigsaw puzzle without the box top and thousands of pieces of other jigsaw puzzles mixed in among them that look like they would it but really don’t fit. So, after the fact, you know precisely what to look for and you can find a dozen pieces you can put them together and understand what may have happened and what might have been missed. In the lead up, it’s a different picture. So that was 9/11 and the aftermath to it involved a tremendous work of effort and focus at the agency. And I was privileged to be in there and help tell as much of that story as we could at the time and help try to explain the things that we couldn’t answer, and trying to explain why we couldn’t answer the question.

That whole atmosphere played into the next one that you mentioned, the run up to the Iraq War. You can’t overstate how much impact of 9/11 had on the thinking within the administration about dealing with the potential threat of Iraq. And there were a couple mainstream ideas that touched on things that I was able to deal with at the time, one was the terrorism threat and there were a lot people who were connecting Iraq to al-Qaida, inappropriately we thought. They were over-stressing, this is outside the intelligence community, over-stressing the potential connection between Saddam Hussein and al-Qaida. And I spent a lot of my time, to the extent that I could, factually dealing with that, trying to knock down the notion that there was some direct link between Saddam Hussein and Al-Qaida. Things like that. And then there was the WMD portion and as Paul Wolfowitz famously said at one point, “That was the one thing that everyone could agree on.” This includes every intelligence service around the country, even Saddam’s, I would bet you. Every pundit for the most part was pretty well convinced that Saddam had some fashion of weapons of mass destruction. Turned out that it was nowhere near as far along as feared. And you can write books, and I’ve help write a couple, thinking in to a great detail about how did it happen, how it could’ve happened. But it was a tremendously complex period in the country’s life. And there was a feeling of “we don’t want to get this one wrong. If we get this one wrong and we underestimated it, the results could be catastrophic.” You could argue though we got it wrong in the other direction, and we certainly did, but it was a difficult period and the life of the intelligence community in the country’s history.

MM: And then not too long after that, you ended up retiring from your role and then taking that experience to the ventures that you are working on now. So, the PR firm, Bill Harlow Communications, and also 15 Seconds that you mentioned earlier that you co-founded with Fred Francis from NBC. So, what was that transition like, to go from what must have been the most difficult part of your career dealing with 9/11 and the lead up to the Iraq War and the immediate aftermath, into the private sector just all of a sudden. Was it a difficult transition, was it hard to learn the new tricks and tips and things that you have to figure out? Or was the transition relatively smooth? What kind of things did you learn what things in your previous career helped you find a new one?

BH: Yeah, well backing up a little bit, I had actually retired from the Navy before I took the job at the CIA. So, I had been out of the Navy for a while, and although I left the Navy on a Friday and started on Monday at the CIA, the only difference was showing up in civilian clothes. But there wasn’t much difference between those 25 years in the Navy and seven years at the CIA. Then all of a sudden, I left the CIA. Frankly after 33 years of fairly intense service, I was kind of exhausted, so I welcomed the opportunity to not show up at work at 5:30 or 6 in the morning every day, and stay until 7 or 8 at night.

Initially, one of the things I was able to pursue shorty after leaving the agency was to help George Tenet with his memoirs, which were published in 2007, in a book called At the Center of the Storm. And that too was a fairly intense process, a very difficult one to figure out what could be said, help him get it written and get it through the CIA clearance process which is challenging. So that kept me busy, and at the same time, I was setting up this other company 15 Seconds with Fred Francis where we were trying to pitch ourselves to both the private sector and we had a few governmental clients as well where we helped train people to deal with the media. So, all that kept me busy and it was an interesting change of pace. So, it wasn’t as difficult a transition as I might have feared

MM: And so with all of those things that ended up happening to you, how much of that did you say did you build intentionally? How much happened by luck?

BH: I think about 90 percent of life is luck. You just keep showing up to the work and doing the best you can and networking at the extent that you can. I never planned to spokesman for the CIA. In fact, when I retired from the Navy, the one thing I didn’t want to do was go back to work for the government. At the time you had to give up most of your retired pay if you went back to work as a civil servant and that made no sense for me to do that at all so when the guy who was spokesman for CIA was leaving at the time I was shopping around for a job, and I knew him from the Pentagon in the past, he asked me if I wanted to go over for an interview for his job. And I had no intention of getting that job, I thought it might be good practice to interview over there and then when I went out to the private sector I’d have more practice with job interviews.

Because usually in the military you don’t do job interviews, that’s not really the way you get assignments. So, I went over there thinking I would work my way up the bureaucracy with people and I’d practice my interview skills. Well, the first guy in the interview was George Tenet. And I just hit it off with the guy, just was totally impressed with him, and I thought, “you know it might be fun to work with him for a year or two and then go off and into the private sector.” Well, a year or two turned into seven years and I never planned it that way, but it turned out to be a wonderful thing. I didn’t anticipate that so many historic things would happen when they did and I helped convince him that he ought to tell his story, and then he asked me to help me do it and then one thing led to another. I think that if he tried to plan it then that never would have happened. When I went to the White House and I was only going there for nine months, it was a temporary job and I had no way of knowing that President Bush would be elected or that he would ask Marlin Fitzwater to stick around or that Marlin would ask me to stick around. So, it was just the luck of the draw and I’ve been very lucky.

MM: So then let’s talk a little bit more about the crisis communication aspect, since you’ve lived through crises. I imagine your firm 15 Seconds has something to do with crisis communications so if you could walk us through why did you founded that particular organization company and what is it like to handle crisis communications, how do you do it, and how is it different from non-crisis public relations.

BH: We call the company 15 Seconds, it’s sort of a play on Andy Warhol’s in the future everybody will be famous for 15 minutes. He said that 40 years ago and things have sped up so much that you only get 15 seconds. And our theory is that in a crisis situation you’ve got to respond enormously fast in order to get ahead of the curve and in order to establish what you’ll want to say because everybody else is going to be out there: all your competitors, all of the people who are your opponents, all your pundits, all the people who are just looking to get some notoriety will be out there talking about your issue whether you want to be or not. So, the difference between crisis communications and normal public relations, is that you don’t really get a vote on whether you play or not. If you’re at Equifax and you’ve just been hacked and lost the details of 143 million people, you got to get out there and talk about it whether you like it or not because otherwise your company’s going to be decimated. In normal situations, people in organizations can pick and choose, “Do I want to engage, do I not want to engage, do I want to put out a spokesman, do I want to just respond in a written response, can I just let this go and keep your head down and maybe we’ll do fine?” But in a crisis situation, you’ve got to play, because otherwise you’re just going to get your head handed to you because everybody else is going to be damning you, putting out information which may or may not be true, and redefining your organization. So, it’s a challenge and we think that organizations who only think about crisis communications after the crisis hits have put themselves in a very difficult position. Because if they haven’t thought through how you would respond to a crisis, if you haven’t thought through who would be your spokesman on it, if you haven’t thought through mechanisms on how we get information out, “do I put out a press release, do I put out a press conference, do I know how to hold a press conference, do I know where to hold it?” If you haven’t thought through it in advance, the chances of it coming out perfectly well aren’t so good.

MM: Let’s talk also then about the part of your career that you alluded to when you were talking about helping write At the Center of the Storm with George Tenet, his memoirs. You’ve written a number of other books too, one with Michael Morell and a number of others, primarily about al-Qaida and the war on terrorism. How did you end up deciding to pursue that business model of helping others write their stories and how is that different from other kinds of writing that you have to do either in your private sector or in your public-sector PR roles?

BH: Well, the first book I wrote was actually a novel that I wrote towards the end of my time in the navy, called Circle William. And it was about two brothers, one who was a White House press secretary, obviously based on my experience, and the other was a captain of an Arleigh Burke destroyer, and that was actually based on a friend of mine and yours, Jim Stavridis. I had worked with him within the secretary of the navy staff, and when he was a young commander. So using those two worlds of the Navy and the White House press operation, I worked on this novel which was well-received. I wasn’t able to promote it that much because by the time it came out I was at the CIA and I had a full-time job but it was an interesting experience as simply getting published is both rewarding and challenging. So, I had been through the process.

Then at the end of my time at sea, I had been published once at least and I knew the mechanics of doing it. I had this belief that George Tenet had a terrific story to tell and I wanted to help him tell it and it came out very well. His book opened number one in the New York best seller list, you can’t complain about that. But I didn’t intend to get into that line of work, but having done that successfully with Tenet, other book opportunities presented themselves to me. Fortunately for every book that I have coauthored, the people I worked with were first friends before coauthors, so Michael Morell and then Jose Rodriguez, and Jim Mitchell is the most recent one.

So, these are people I certainly knew of and in most cases, knew well and were friendly with. And that made the process a lot easier to help them tell their stories. Of course, this is their story, it’s not my story, but they’re also all very busy people and the extent that I could help them convey what they want to convey, about their lessons learned from their time and any government, it’s been a worthwhile and rewarding experience.

MM: Since you’ve done this a number of times already, do you have any writing advice for our people out in our audience, who I imagine most are more used to say, writing articles for CIMSEC or doing background papers in their government jobs? Any writing advice that you gleaned from both your time in uniform, and as a government civilian, and as a writer?

BH: One bit of advice would be to keep writing, it’s something that gets better, and it gets easier the more you do it. And to the extent that if you let that skill atrophy, it takes a while to get back in the saddle. And don’t let the perfect be the enemy of the good. Just keep writing and writing. The other bit of advice is, to paraphrase Elmore Leonard, when you’re writing, leave out the parts that people are going to skip anyway. I see a lot of people writing things and it is way too long. I get a lot of former CIA and military people who want to write novels or non-fiction books who come to me and ask for some advice, and what I tend to see is that they write too much. People who write books which if they ever got published would kill thousands of trees. It’s much better to leave people wanting more than to have them wanting less. So, to the extent that you write stuff, if you could keep it punchy, memorable, short, it’s to your advantage. Other times, where you need to write long, the Tenet book, At the Center of the Storm, was a pretty hefty sized book, but he had so much material to cover and so many historical things that justified it. But for most of us, writing material to keep it punchy and short is much better.

MM: Excellent. Now since we’ve reached the end of our episode, let’s conclude the same way we conclude every episode. Especially since you’ve worked in communications, you likely know this question well, what kind of things are you reading nowadays, and for the people out in the audience who are either interested more in the public relations and public affairs world or just interested in what’s on your mind, what things would you recommend that they pick up?

BH: I don’t read a whole lot about the public affairs world, so I may let down your readers on that regard. I tend to find myself reading more nonfiction historical stuff, that’s what interests me and that, when I break away from my daily routine, is what I tend to focus on. One book I’m reading right now is Churchill and Orwell, by Tom Ricks, terrific book, I’m only about halfway through it but I would never have thought to have combine those two people in a single book, but Tom is doing a great job, has done a great job telling two stories of two quite remarkable men during a critical period in the world’s history. Tom is somebody I knew, he was a correspondent from the Wall Street Journal and he’s someone who has given me writing advice early on, so I certainly respect everything that he does. I also read stuff that is sort of on the periphery of things that I have done or there’s a number of books by former CIA officials or people who are interested in CIA things. There’s one coming out from the Naval Institute Press called Operation Blackmail about Betty Macintosh, who was a woman in the OSS in World War II in the Pacific, who led a remarkable career. And that’s a book I read in galley form. It’s well worth a read by people who read your blog and who are interested in World War II history and espionage. It’s quite a remarkable book.

MM: I’ll definitely have to pick it up I’m sure. Thank you again Bill for taking the time today. Really appreciate you appearing on Sea Control and best of luck in all of your ventures, writing, and communications and otherwise.

BH: Thank you very much, it’s been my pleasure.

Bill Harlow is the President of Bill Harlow Communications and Co-Founder of 15-Seconds.com. He is the author of Circle William and has co-authored a number of books, including At the Center of the Storm with George Tenet and The Great War of Our Time with Michael Morell.

Matthew Merighi is Senior Producer for Sea Control, CEO of Blue Water Metrics, and Assistant Director for Maritime Studies at Tufts University’s Fletcher School.