The Red Queen’s Navy

Written by Vidya Sagar Reddy, The Red Queen’s Navy will discuss the  influence of emerging naval platforms and technologies in the geostrategic contours of the Indo-Pacific region. It identifies relevant historical precedents, forming the basis for various maritime development and security related projects in the region.

influence of emerging naval platforms and technologies in the geostrategic contours of the Indo-Pacific region. It identifies relevant historical precedents, forming the basis for various maritime development and security related projects in the region.

“Now, here, you see, it takes all the running you can do, to keep in the same place.”– The Red Queen, Through the Looking Glass, Lewis Carroll.

By Vidya Sagar Reddy

A recent RAND report underscored the significance of the strategy by certain states of employing measures short of war to attain strategic objectives, so as to not cross the threshold, or the redline, that trips inter-state war. China is one of the countries cited by the report, and the reasons are quite evident. The employment of this strategy by China is apparent to practitioners and observers of geopolitics in the Indo-Pacific region. The diplomatic and military engagements in this region call attention to the South China Sea, where China’s provocative actions continue to undermine international norms and destabilize peace and security.

Vietnam and the Philippines are the two claimants determined to oppose such actions with the support of other regional security stakeholders. They intend to shore up their military strength, especially in the maritime domain. The Philippines decided to upgrade military ties with the U.S. through an agreement allowing forward basing of American military personnel and equipment. It will receive $42 million worth of sensors to monitor the developments in West Philippine Sea. Additionally, India emerged as the lowest bidder to supply the Philippines with two light frigates whose design is based on its Kamorta class anti-submarine warfare corvette.

The recent visit of US. President Obama to Vietnam symbolizes transformation of the countries’ relationship to partners and opened the door for the transfer of lethal military equipment. Vietnam is considering the purchase of American F-16 fighters and P-3C Orion maritime patrol aircraft. Its navy is already undergoing modernization with the induction of Russian Kilo class submarines. India, which uses the same class of submarines, helped train Vietnam’s submariners. Talks with Vietnam to import India-Russia joint BrahMos supersonic anti-ship cruise missiles seem to be in an advanced stage.

But, this military modernization is concentrated on strengthening the conventional domain of the conflict spectrum, while China accomplishes its objectives by using sub-conventional forces. China’s aggressive maritime militia and coast guard are the real executors of local tactical contingencies, while its navy and air force provide reconnaissance support and demonstrate muscle power.

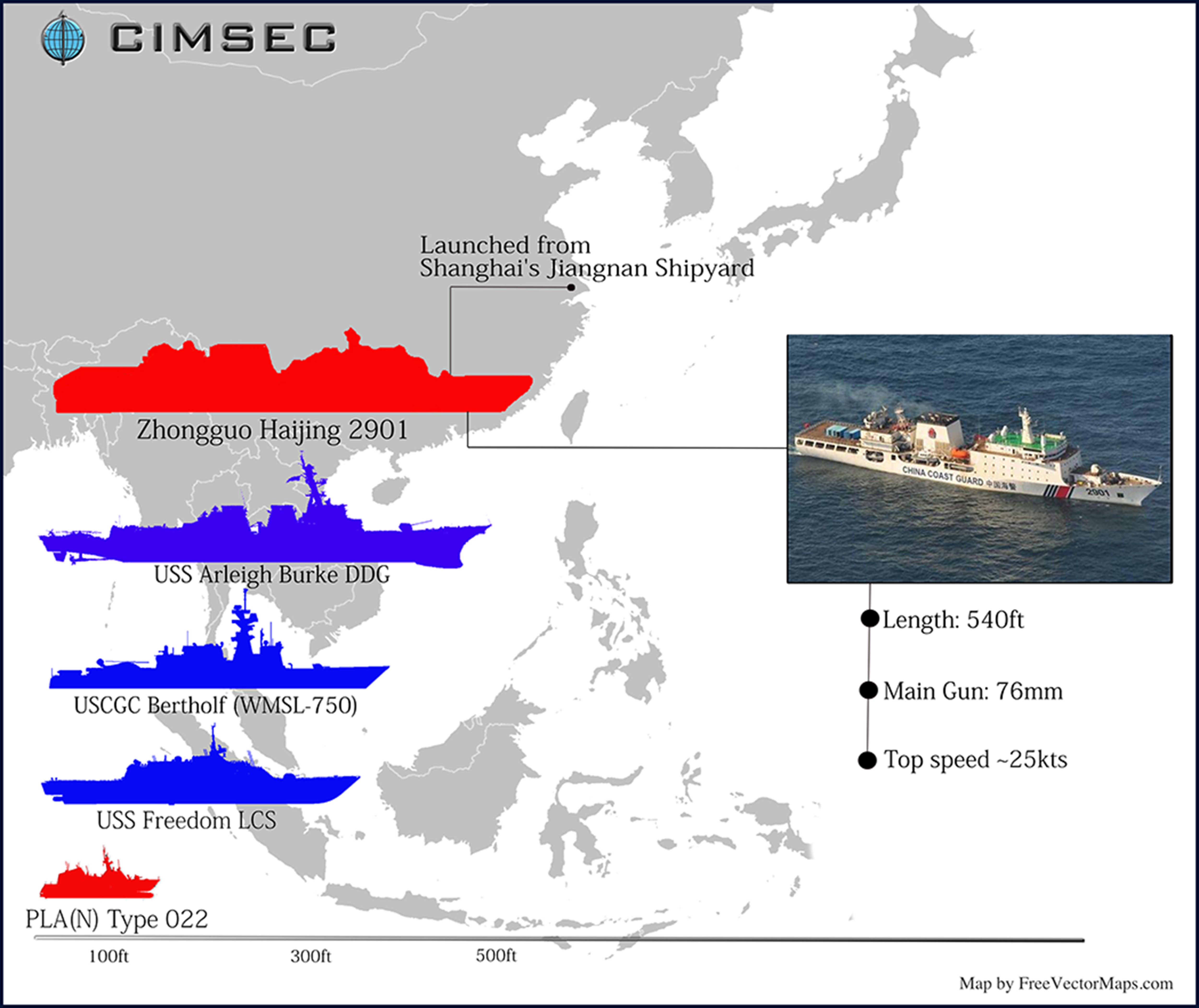

The 2014 HYSY 981 oil rig stand-off, when China’s vessels fired water cannons and rammed into Vietnamese boats, serves as a classic example of China’s use of sub-conventional forces. Some of these platforms are refitted warships, and the total vessel tonnage has far exceeded the cumulative tonnage of neighboring countries. China has also deployed coast guard cutters weighing more than 10,000 tonnes, the largest in the world. They cover maritime militia’s activities like harassing Vietnamese and other littoral fishermen from exercising their rights or defend China’s illegal fishing activities in the exclusive economic zones of other countries. Recently, they have forcefully snatched back a Chinese fishing vessel that had been detained by the Indonesian authorities for transgression.

Such provocative actions to forcefully lay down new rules on the ground need to be challenged, but using conventional air and naval assets will only lead to escalation. It is advisable to learn from China’s strategist himself in this context, Sun Tzu, who counsels that it is wise to attack an adversary’s strategy first before fighting him on the battlefield.

Therefore, both Vietnam and the Philippines must also concentrate on building up the capacity of respective coast guards and maritime administration departments with relevant assets like offshore patrol vessels (OPV) to secure the islands and exclusive economic zones. Operating independently in these areas inevitably hedges against China’s proclamation of South China Sea as its sovereign territory and requiring its consent to operate in.

Vietnam is inducting patrol boats furnished by local industries as well as depending on the pledge from the U.S. to provide 18 patrol boats. The Philippines contracted a Japanese company to build 10 patrol vessels on a low-interest loan offered by Japan’s government. It is also set to receive four boats from the U.S.

India should also take a proactive position and join its regional security partners in extending its current efforts in the Indian Ocean to the South China Sea. India has built high level partnership programs to build the capacity of its neighboring Indian Ocean countries to ensure security of their exclusive economic zones. In the process, it delivered some of its OPVs to Sri Lanka. Recently, Mauritius became the first customer of India’s first locally built OPV Barracuda. India is now building two more for Sri Lanka. Additionally, Vietnam has contracted an Indian company to build four OPVs using the $100 million line of credit offered by the Indian government.

The demand for these vessels will only grow as the strategic competition in the South China Sea escalates. India enjoys better political, historical, and security relations with the South East Asian countries, especially Vietnam. The Philippine government has underscored this relationship between India and Vietnam as the foundation for its own relations with India. Taking advantage of this situation not only improves India’s strategic depth in the region but also enhances its manufacturing capacity that is at the core of Make in India initiative.

The specific requirements like range, endurance, and armament depend on the customer countries. The more critical question at play is whether the regional security stakeholders are comfortable with the idea of upgunned coast guards along the South China Sea littoral.

The U.S. has forward deployed four of its Littoral Combat Ships (LCS) to Singapore to tackle a variety of threats emanating in the shallow waters. The ships are smaller than a frigate but larger than an OPV in terms of sensor suites, armament, mission sets, and maintenance requirements. War simulations proved that upgunned LCS can cross into blue water domain with ease and complicate an adversary’s order of the battle.

Vietnam and the Philippines could specify higher endurance, better hull strength and advanced water cannons for their OPVs to defend proportionally against Chinese vessels. In addition to manufacturing ships, India should also train Vietnamese and Philippine forces on seamlessly integrating intelligence from different assets for maritime defense.

Over time, a level of parity in the sub-conventional domain needs to be achieved and maintained to force China to either shift its strategy or escalate the situation into conventional domain whereupon the escalation dominance will shift to status quo countries.

Vidya Sagar Reddy is a Research Assistant at the Observer Research Foundation, New Delhi.

Featured Image: Chinese 10,000 ton coast guard cutter, CCG 2901. (People’s Daily Online)