By Natalie Sambhi

Indonesian Foreign Minister Natalegawa has recently articulated his proposal for an Indo-Pacific Treaty at no less than three different conferences (including ‘Intersections of Power, Politics and Conflict in Asia’ in Jakarta in June) and it bears careful reading because it contains ambitious ideas.

To summarise his proposal, Natalegawa sees the Indo-Pacific region as beset by a deficit of ‘strategic trust’, unresolved territorial claims, and rapid transformation of regional states and the relationships between them. The potential for these factors to cause instability and conflict requires the region to develop a new paradigm, an Indo-Pacific wide treaty of friendship and cooperation, to encourage the idea of common security and promote confidence and the resolution of disputes by peaceful means. At present, Natalegawa has only provided the broad concepts behind the treaty but a precursor question is whether a treaty is really necessary?

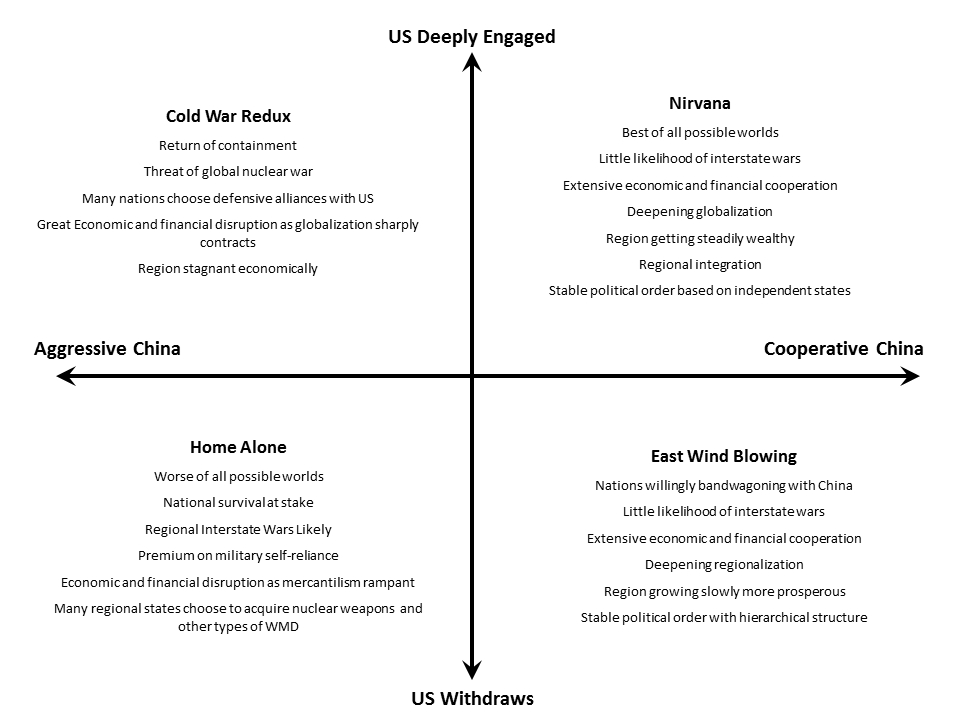

Natalegawa argues that the Indo-Pacific region needs to be thought of as its own separate system. By having a treaty, regional states will start to think of themselves as members of a community responsible for common security. But the appeal of the idea depends on whether you consider multilateral agreements effective in encouraging member states to cooperate. Less powerful states in the Indo Pacific have few means to contribute to regional stability other than engaging more powerful states. In talking about managing the rapid transformation of regional states, Natalegawa espouses his idea of ‘dynamic equilibrium’ which entails ‘no preponderant power’. Rather than allow the region to be dominated by bilateral tension between powerful actors, Natalegawa argues their interests are inter-linked. The US and China, along with India and Japan are thus encouraged to see their actions in the context of ‘common security’.

The Indo-Pacific is an important geostrategic and economically significant area but it’s a long way from being a formal institution. Indonesia, a non-aligned state located at the geo-strategic centre of the system, might see itself as an obvious choice of broker for this treaty. However, the Indo-Pacific is, at best, a nascent ‘system’, and there’s no central body like ASEAN driving the process for this treaty. In absence of such a framework, it’s hard to see how Indonesia will be able to bring regional countries even to the negotiating table.

The Treaty of Amity and Cooperation in Southeast Asia and the East Asia Summit’s Bali Principles both had ASEAN providing the diplomatic management for negotiating these agreements. They too encourage member states to build ‘strategic trust’, renounce the use of force and settle disputes by peaceful means, as well as include norms like the promotion of ‘good neighbourliness, partnership and community building’. Yet, they’ve had limited effectiveness as a mechanism for action or conflict prevention. Almost all of the so-called ‘Indo-Pacific’ states belong to one or both of these agreements, but no multilateral system has yet demonstrated the ability to ensure that all states adhere to those norms.

In order to effectively tackle the region’s security challenges, including the rapid social and economic transformation of states and the friction this might bring, there needs to be a strong incentive to cooperate and a mechanism for conflict management. The proposed treaty, like the previous two, provides neither.

Security issues between ASEAN states show a clear preference for bilateral resolution. Most recently, smoke from burning forests in Sumatra last month blanketed Malaysia and Singapore in the worst haze since 1997, with severe risk to health. First Singapore then Malaysia sent their representatives to Jakarta to urgently discuss a solution with the Indonesian government. An agreement signed by ASEAN states in 2002 to tackle haze hasn’t been ratified by Indonesia. Instead, at an ASEAN–China Ministerial Dialogue in Brunei earlier this week, Singapore, Malaysia and Indonesia agreed to a trilateral process to manage fires and haze in future—the three states have a clear interest in cooperating on this issue. ASEAN can provide a forum to discuss the haze but, when push comes to shove, the actions of Southeast Asian states demonstrate a tendency to bypass the ASEAN framework.

Similarly, China’s assertive and uncooperative behaviour towards the Philippines over the Scarborough Shoal is at odds with the TAC and Bali Principles. China’s made clear its preference for bilateral engagement with other territorial claimants and to avoid international courts. Without the most powerful states in the ‘Indo-Pacific system’ backing the treaty, norms (in this case, the expectation that states won’t resort to the use of force or coercion) won’t provide the restraint needed. States will continue to rely on traditional alliance partners for protection or to provide a balance to other aggressive actors.

Multilateral frameworks in parts of the Indo-Pacific have been most effective when they have formed for a clear purpose. As Victor Cha argues, coalitions have formed ‘among entities with the most direct interests in solving a problem’. I think the best we can expect for now is a complex network of overlapping agreements and groupings that form to solve clearly defined and immediate issues. Direct interests will yield definite action. The Indo-Pacific treaty could build trust in the long term and as a proposal for more order-building in a transformational Asia, it shows Indonesia trying to lead the way. But if the strategic outlook is as dire as Natalegawa describes, I’m doubtful a new treaty is what we’ll need to tackle some of the region’s most pressing security challenges.

Natalie Sambhi is an analyst at ASPI and editor of The Strategist. Image courtesy of Indonesian Foreign Ministry. This post first appeared at the Australian Strategic Policy Institute (APSI)’s blog The Strategist.