The following article is special to our International Maritime Shipping Week. While we often discuss the threats to maritime shipping, this week looks at dangers arising from such global trade, and possible mitigations.

“Where the carcase is, there will the eagles be gathered together.”

Julian S. Corbett, Some Principles of Maritime Strategy (1911)

In a global system marked above all by its complexity and interconnectedness, dependence on international shipping is universal. Yet some nations are far more vulnerable than others. As students of naval history well know, such vulnerability is often turned into a source of strategic leverage. To what extent can this leverage actually be exploited under 21st century conditions?

The globalized economy is, in a very real sense, a system of maritime exchange. As Thomas Friedman points out, as much as any other recent innovation, it was the shipping container that shaped our daily lives by making the economic transformation of the late 20th Century possible.[1] In the past two decades alone, the volume of sea-borne commerce has more than doubled, from 4 billion tons in 1990 to 8.7 billion tons in 2011. According to the International Maritime Organization, if the overall trend of trade growth observed over the last one and a half centuries continues, the figure will be 23 billion tons in 2060. And, while the exact share of global trade in goods that is moved by is a matter of some debate, it is sea well in excess of 75 percent by most reckonings. Further, it is clear that only cheap and plentiful shipping in a secure maritime environment can sustain this transformation. As a result, the stakes in international shipping are widespread.

But while any nation that wishes to prosper in the current global environment shares in the global dependency on shipping, the vulnerabilities that arise from it are distributed unevenly. This is mainly for two reasons: First, the degree to which specific nations sustain themselves by means of ship-borne imports, and to which they found their prosperity upon maritime exports, varies greatly. Secondly, depending inter alia on a country’s geopolitical setting, it will be more or less able to manipulate the degree to which it has to rely on shipping for its economic security. A resource-rich, continental-size state with landward access to sizeable markets – like Russia – has serious alternatives to maritime transportation. A small island nation with an export-oriented economy that runs on imported hydrocarbons – such as Taiwan – does not. It is where dependency gives rise to vulnerability that it turns into a potential source of leverage for outside powers.

Targeting Shipping for Strategic Effect

In what ways can vulnerabilities in the area of maritime transportation be exploited for strategic effect? There is, of course, a whole spectrum of options available to would-be-predators. Unilateral or multilateral sanctions have been a mechanism of choice since the end of the Cold War. But historically, it has been direct military action against the opponent´s shipping that has had the greatest impact on trade. Two main methods of waging war on commercial shipping can be distinguished, at least at an analytical level: (1) the blockade, and (2) guerre de course, or commerce raiding. The blockade relies on concentration and persistence to choke off the flow of sea-borne goods into enemy harbors, and as such will usually require some form of command of the sea. Commerce raiding, on the other hand, relies on dispersed, attritional attacks by individual vessels (or small groups of vessels), which makes it an attractive option for navies that find themselves in a position of inferiority. Both methods leverage the disruption of shipping to impose a cumulative toll on the adversary’s economy, which is expected to have a significant indirect impact on the war effort and/or erode the opponent´s will to resist.

Historical examples of shipping being turned into a strategic lever are abundant. In the age of sail, preying on adversaries’ commerce was an integral part of most naval campaigns, including those of the Dutch Wars, the Seven Years’ War, and the Wars of the French Revolution. While it was seldom decisive, it was often “exceedingly painful,”[2] as Colin Gray observes. During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, innovations in naval technology all but brought to its termination the “close blockade” of enemy harbors while also providing means – the submarine, torpedo, and naval mine – that would transform guerre de course into a method of total warfare. Much ink has been spilled on Germany’s failed – and strategically counterproductive – attempts subdue Britain by way of Handelskrieg (the German variation of commerce raiding), while a slightly more specialized literature focuses on the “distant blockades” of Germany that were a key feature of British naval operations in both World Wars. However the case of Japan is most the instructive for the purposes at hand.

Historical examples of shipping being turned into a strategic lever are abundant. In the age of sail, preying on adversaries’ commerce was an integral part of most naval campaigns, including those of the Dutch Wars, the Seven Years’ War, and the Wars of the French Revolution. While it was seldom decisive, it was often “exceedingly painful,”[2] as Colin Gray observes. During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, innovations in naval technology all but brought to its termination the “close blockade” of enemy harbors while also providing means – the submarine, torpedo, and naval mine – that would transform guerre de course into a method of total warfare. Much ink has been spilled on Germany’s failed – and strategically counterproductive – attempts subdue Britain by way of Handelskrieg (the German variation of commerce raiding), while a slightly more specialized literature focuses on the “distant blockades” of Germany that were a key feature of British naval operations in both World Wars. However the case of Japan is most the instructive for the purposes at hand.

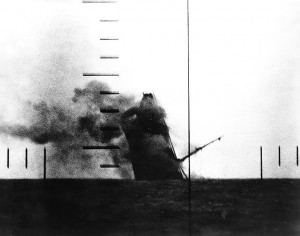

An island nation with an extremely circumscribed resource base, Japan was utterly dependent on ship-borne imports of a range of raw (and precursor) materials. In a very real sense, the Empire´s huge naval modernization program during the 1930s was based on its maritime commerce with the United States. Among other things, the U.S. covered 80 percent of Japanese liquid fuel needs. Given its political and military trajectory, Japan´s demand for key commodities was highly inelastic. The only alternative to trade with the United States and other potential adversaries was the unilateral extraction of resources from Japan´s near abroad – which could decrease its dependence on this particular foreign power, but (crucially) not on maritime transportation. When war came, the U.S. was able to exploit this vulnerability to devastating effect. Despite the many operational and technical inadequacies revealed by its initial operations in 1941-42, the U.S. Navy´s all-out war on Japanese shipping eventually came as close to strategically decisive as can reasonably be expected from any indirect use of military power.[3] Aided by the dire lack of defensive measures on the part of the Imperial Japanese armed forces, U.S. submarines alone sent more than 1,100 Japanese merchantmen to the bottom, and nearly as many were sunk by aircraft and mines. By the spring of 1945, Japanese sea-borne logistics had virtually ceased to exist, and so had Japan´s ability to sustain its war effort.

It has been suggested that other attempts throughout history at disrupting shipping flows might well have been equally successful in exploiting strategic vulnerabilities, had it not been for the predators´ “technical incapacity, operational ineptitude, and policy incompetence […] in the conduct of commerce raiding.”[4] Whether this assessment is accurate or not, there is little doubt that – despite the moral opprobrium that has often accompanied attacks on civilian vessels – the vulnerable dependence on sea-borne trade can be exploited to considerable effect. What relevance this finding might possess in an era of global economic integration is, however, much less clear.

Execute against China?

Until very recently, the explosion of maritime trade supporting economic globalization has not resulted in a resurgence of military strategies based on the (selective) disruption of international shipping. An important exception has been Iran´s focus on the Strait of Hormuz, which has played a critical role in Iranian strategic thinking since the 1980s. But it is the rise of China that has reignited naval strategists´ interest in shipping as a source of strategic vulnerability.

One set of scenarios that has been debated in detail involves Chinese offensive operations against Taiwan´s economic lifeline. Given the island´s vulnerable dependency on shipping and the enduring limitations of the People´s Liberation Army with regard to a full-scale invasion, it is hardly surprising that the imposition of a coercive blockade should hold some appeal in PLA planning circles.

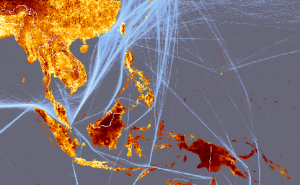

Considerably greater attention has been attracted, however, by the possibility that the People´s Republic might itself become the target of offensive military action against the sea-borne commerce on which the integrity of its economic model stamds. After all, 90 percent of China’s exports and 90 percent of its liquid fuel imports – which, as Sean Mirski observes are “functionally irreplaceable”[5] – are transported by sea. The oft-cited ‘Malacca dilemma’ is but one expression of a suspicion that now unites an increasing number of strategic thinkers, both Chinese and foreign: namely, that its dependence on maritime transportation may prove to be China´s Achilles’ heel on its way to greatness.

While the vulnerability of the PRC’s sea lines of communications has become an official justification for naval expansion and a rallying cry for naval nationalists, it is also a focal point for U.S. strategizing in the context of increasing access challenges in the Western Pacific. Thus, a blockade of Chinese (or rather China-bound) shipping has been debated both as an element of, and as an alternative to, the AirSea Battle Concept that is designed to enable operations in the face of an anti-access/area-denial challenge, such as U.S. military planners anticipate in case of conflict along the Chinese periphery.

While Western treatments of the subject tend to agree that a blockade would be militarily feasible – given an adequate investment of resources – and could have a very considerable impact on the Chinese economy, the assumptions under which they arrive at these conclusions are extremely restrictive. For example, Mirski assumes that (1) the U.S.-China conflict in question would not be limited in scope, yet would stop well short of nuclear use, (2) the U.S. would find itself in the position of defender of the status quo against a blatantly aggressive China, (3) the U.S. would be able to build a coalition that includes Russia, India, and Japan; and (4) under these conditions, a ‘sink-on-sight’ policy towards civilian vessels in China’s near seas would be politically viable. Even with these preconditions, he concludes that despite the American blockade “China would be able to meet its military needs indefinitely.”[6]

While Western treatments of the subject tend to agree that a blockade would be militarily feasible – given an adequate investment of resources – and could have a very considerable impact on the Chinese economy, the assumptions under which they arrive at these conclusions are extremely restrictive. For example, Mirski assumes that (1) the U.S.-China conflict in question would not be limited in scope, yet would stop well short of nuclear use, (2) the U.S. would find itself in the position of defender of the status quo against a blatantly aggressive China, (3) the U.S. would be able to build a coalition that includes Russia, India, and Japan; and (4) under these conditions, a ‘sink-on-sight’ policy towards civilian vessels in China’s near seas would be politically viable. Even with these preconditions, he concludes that despite the American blockade “China would be able to meet its military needs indefinitely.”[6]

Recent publications also points to changes in the nature of international shipping itself as potential complicating factors: in a prospective blockade scenario, few – if any – civilian vessels would fly the Chinese flag and, given the practice of selling and reselling cargo on spot markets, a ship´s final destination might not be known until it actually enters port.[7] But while Mirski’s proposal of instituting a system of digital navigational certification is ingenious, he dodges the broader question of how the United States and the nations of the Asia-Pacific would deal with the myriad repercussions of what would amount to a major disruption of the globalized economic sphere for an extended period of time.

Conclusion: Return of the commerce raiders?

If nothing else, the current debate about a U.S. naval blockade of China reveals that – much like their predecessors in past centuries – strategists in a globalized era see shipping as a repository of strategic vulnerability, particularly in cases of high-intensity conflict between great or medium-size powers. But while the potential leverage to be gained from nations’ dependence on international shipping is perhaps greater than ever before, the actual leverage might not correspond to planners’ expectations. The sources of this disconnect lie primarily in the political and economic context in which any concerted military action against sea-borne trade would be embedded. Given the U.S. Navy’s determined stewardship of freedom of navigation, the U.S. in particular would find itself on the wrong side of the norms it has been upholding for the past 60 years. And while the economic fall-out of any great power war is likely to be significant, the willful disruption of trade flows for strategic effect would only serve to accentuate the costs to regional allies and global trading partners.

As a result, unrestricted commerce warfare of the type pursued by the U.S. Navy against Japan in 1941-45 is just not in the cards. On the other hand, anything short of a strategically counterproductive ‘sink-on-sight’ policy might not produce sufficient strategic impact to justify the cost of embarking on such a risky course of action in the first place. Finally, once we move beyond the context of open interstate warfare, multilateral economic sanctions offer the possibility of causing many of the same effects at markedly lower cost to the attacker’s international standing.

Overall, the recent surge of interest in economic warfare strategies does little to encourage faith in the potential decisiveness of military actions against globalized trade, and serves to underline the practical and political challenges presented by any attempt at leveraging the vulnerabilities of a major trading power under 21st-century conditions. While the dependence on international shipping poses many risks, the strategic leverage it provides as a direct result of its crucial contribution to the prosperity of nations is now more apparent than real.

Michael Haas is a researcher with the Global Security Team at the Center for Security Studies, ETH Zurich. The views presented above are his alone. Michael tweets @the_final_stand.

[1] Thomas L. Friedman (2006), The World Is Flat: The Globalised World in the Twenty-first Century (London: Penguin), 468.

[2] Colin S. Gray (1992), The Leverage of Sea Power: The Strategic Advantage of Navies in War (New York: Free Press), 13.

[3] Robert A. Pape (1996), Bombing to Win: Air Power and Coercion in War (Ithaca, NY: Cornell UP), 100-01.

[4] Gray 1992, 13.

[5] Sean Mirski (2013), “Stranglehold: The Context, Conduct and Consequences of an American Naval Blockade of China,” Journal of Strategic Studies 36:3, 389.

[6] Mirski 2013, 416.

[7] Ibid., 402; Gabriel B. Collins and William S. Murray (2008), “No Oil for the Lamps of China?,” Naval War College Review 61:2, 84.