Guest post for Chinese Military Strategy Week by Xunchao Zhang

In May 2015, it was reported that China was going to establish a naval base in the East African nation of Djibouti. In the past, there has been much talk about Chinese overseas bases, but the Chinese official response to this news suggest the base is likely to be more than a rumor. The Chinese Foreign Ministry did not deny the report but instead stated that “Regional peace and stability serves the interests of all countries and meets the aspirations shared by China, Djibouti and other countries around the world. The Chinese side is ready and obliged to make more contributions to that end.” Likewise, the Chinese Defense Ministry also expressed China’s willingness to “make even more contributions” to peace and stability of the region. More directly, the official Xinhua News Agency has argued that time is ripe for a base in Djibouti. The talk of a Chinese naval base in Djibouti seems to confirm a 2014 report from Washington predicting the establishment of Chinese “dual-use” bases in the Indian Ocean serving both commercial and security functions. All of this brings to mind three questions: First, why would China choose to increase its Indian Ocean presence? Second, what is the strategic environment in which China has to operate? And third, what are the strategic implications for Sino-U.S. strategic interactions and China’s maritime strategy?

Strategic Rationale

The increasing importance of the Indian Ocean to vital Chinese maritime interests form the rationale of having a Chinese base in the area. Although the official white paper “China’s Military Strategy” did not explicit confirm an out-of-area naval base, it did designate several reasons requiring the People’s Liberation Army Navy’s (PLAN) presence in Indian Ocean. A base in the Horn of Africa is consistent with the strategic shift from solely “offshore waters defense” to a combined “offshore waters defense” and “open seas protection.”

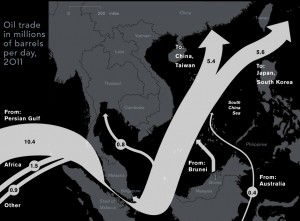

The white paper states that the “traditional mentality that ‘land outweighs sea’ must be abandoned” especially regarding sea lines of communication (SLOCs), of which, exports of manufactured goods and crude oil imports are paramount. Since a significant share of these rely on Indian Ocean sea lines, an out-of-area naval presence is almost a necessity. The February PLAN exercise in Lombok Strait sent a strong signal of the increasing Chinese naval footprint in the Indian Ocean. Moreover, the PLAN has responded to several non-traditional security contingencies near the Horn of Africa. For instance, the PLAN has conducted a series of evacuation operations in the nearby states of Yemen, Libya, and Syria. China has also operated in the Gulf of Aden as a part of the international anti-piracy force since 2008. The official white paper states that the abilities and experiences in dealing with non-traditional challenges should be extended into traditional security areas.

Strategic environment

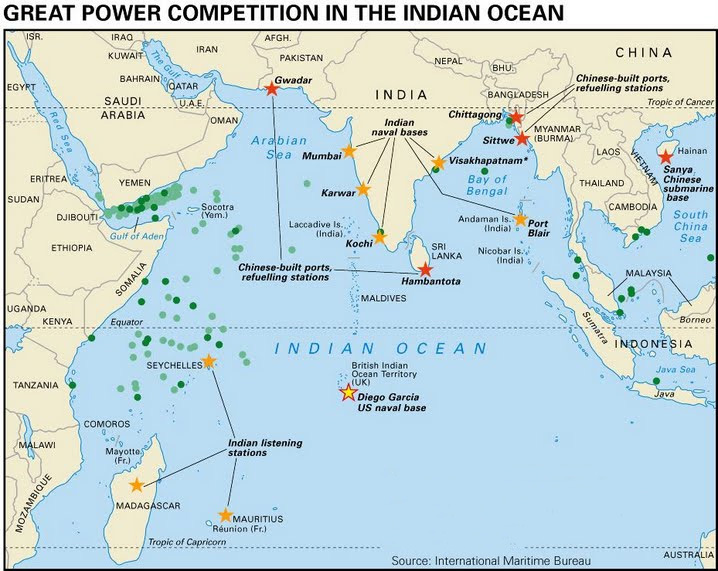

Multiple political and economic factors shape China’s rather favorable environment in the Indian Ocean region. One of the most significant is the lack of direct geopolitical tensions with the regional states. In contrast to the situation in the West Pacific, where China had a wide range of maritime territorial disputes with its neighbors in the South and East China Seas, China has far more cooperative relations with most states in the Indian Ocean region. Beijing not only has strong partnerships with countries like Pakistan but robust commercial and political ties with African states as well.

Under the Xi administration, China has placed greater economic emphasis on the Indian Ocean region. For instance, the recently announced ‘Maritime Silk Road’ involves connecting East Asia with Indian Ocean economies such as India, Pakistan, Kenya and others via the promotion of maritime trade and investment in port infrastructures. Indian analysts have dubbed this the “String of Pearls.” Although the “String of Pearls” concept is an exaggerated reading of largely commercial Chinese infrastructure investments in the Indian Ocean, the scope of Chinese port building does reveal Chinese economic-political weight in the area.

Many international media observers have zealously pointed out the “conflict” between China’s new overseas base strategy with China’s non-interventionist principles. However, overseas basing is not necessarily incompatible with the principle of non-intervention, as long as base arrangements and military deployments are based upon agreement with rather than coercion of foreign governments. A naval base is also irrelevant to the domestic politics of the state where base is to be located. Hence, in technical sense, it is possible for china to establish overseas bases while maintaining the non-intervention principle at the same time.

Strategic Implications

Realistically speaking, China has a long way to go if it is to fulfill the objectives outlined in the recent defense white paper. China would have to overcome not only the overall capability gap with the U.S., but also the lack of experience in running overseas bases, as well as the doubts concerning the cost-benefit calculus of overseas bases. Comparatively, the U.S. military has operated from its own Djibouti base, Camp Lemonnier, during a variety of naval and counter-terrorism missions since 2001. The U.S. base has more than 4,000 personnel and is likely to be much larger and more functionally comprehensive than the potential first Chinese base. Furthermore, as mentioned in the 2014 NDU report, some voices in China are rather skeptical of overseas bases citing concerns about the principle of non-intervention and the possibility of foreign opposition. Therefore, there is possibility that the function of a first Chinese overseas base in Djibouti would be deliberately kept small to avoid controversy. In addition, even in the official white paper, the goal of transformation from “offshore defense” to “open sea protection” remains a limited one, reflecting the Chinese awareness regarding its own limited power projection capabilities.

In terms of overseas naval operations, the Chinese defense strategy white paper clearly took a reassuring tone emphasizing the cooperative and non-confrontational nature of PLAN open sea protection, and SLOCs security objectives. Chinese naval presence in the Indian Ocean region is neither intended to nor sufficient to pose challenge to the current maritime order. But it does indicates an increasing determination on Beijing’s part to provide security for its own overseas interests rather than merely relying on the “public goods” provided by the U.S. Navy. In this sense, China’s increasing Indian Ocean presence, though insufficient to trigger real strategic competition between the United States and China, is certainly feeding the popular narrative of global Sino-US competition in the media.

In sum, the strategic move towards an overseas base is part of the continuation of changing Chinese strategic culture that is increasingly outward-looking and maritime-oriented. But if the base in Djibouti is to be materialized, even in its most limited form, it is certainly a transformative moment in the strategic cultural shift. The increasing PLAN overseas presence, particularly in the India Ocean region is almost a foregone conclusion. However, it depends on how the PLAN is able to deal with its growing pains, the extent and effectiveness of which remain to be seen.

Currently working for the Australian Institution of International affairs, Xunchao Zhang is an observer of Chinese defense and foreign policy, Zhang is also the sub-editor of ACYA journal of Australia-China Affairs. He has been an intern at the Sea Power and Centre Australia, a guest correspondent of China Radio International, and a member of CIMSEC.