This post originally featured on the CDA Institute, and is republished with permission. You can read it in its original form here.

CDA Institute guest contributor Ryan Dean, a PhD candidate at the University of Calgary, offers a reminder on the dangers of inflation in Canada’s defence procurement efforts.

A good portion of our future navy has been sunk on the drawing board by inflation.

Inflation is an economic term that encompasses all the variables that lead to a general price increase in a good or service. In the case of warships, inflation includes everything from technical issues related to the design of the ships to increases in the wages of the shipyard workers who build the ships. The longer a budget takes to be spent, the less that budget can buy.

Military inflation rates have a voracious appetite and can eat through capital budgets far faster than their civilian counterparts. American warships have historically inflated at an annual rate of 9 to 11 percent. The National Shipbuilding Procurement Strategy (NSPS), modeled on American shipbuilding practices, could suffer from even higher inflation rates as we are dealing with the additional time and costs of resurrecting a shipbuilding industry and we do not enjoy the same economies of scale as our southern neighbour in sustaining this strategic industry.

Long delays between the allocation of budgets for a class of warship and their actual construction allows for high inflation rates to halve these budgets. This has already happened with the Joint Support Ship (JSS) and the Arctic Offshore Patrol Ship (AOPS) procurements. It is now happening with the Canadian Surface Combatant (CSC) Project.

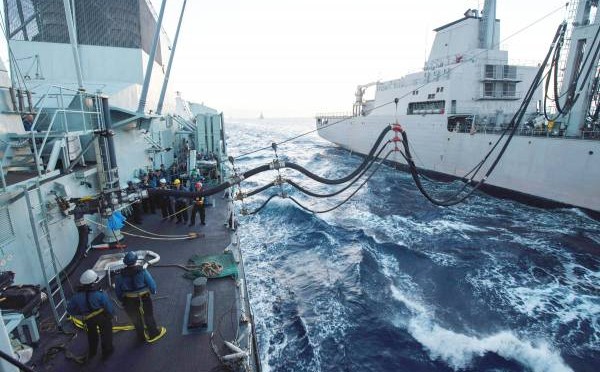

The time invested in designing the JSS to be a highly capable platform backfired. $2.9 billion was budgeted in 2006 to build three replenishment vessels by 2012. Internal pressure for a very ambitious ship led to sealift and command-and-control ashore capabilities being added to the original refueling and resupplies tasks of the proposed vessels. Three “big honking ships,” to borrow the term introduced by General Rick Hillier, with those capabilities could not be delivered within budget and the government rejected bids in 2008. The NSPS effectively pushed things back until 2011, at which time the procurement resumed. In 2013 the “off the shelf” German designed Berlin-class, capable of refueling and resupplying but not sealift and command-and-control, was selected as Canada’s next replenishment vessels with construction beginning in 2016 and deliveries scheduled for 2019 and 2020. Instead of three of these vessels, now only two Queenston-class ships are promised. The negative effects of inflation resulting from years of delays have sunk one of our replenishment vessels on the drawing board.

The AOPS was announced in 2007. $3.1 billion was budgeted to build six to eight ships with deliveries starting in 2013. Based on the Norwegian Svalbard-class, much time and money was invested in attempting to increase the capabilities of the design, though it appears these efforts have largely failed. Time spent on this and the development of the NPSPpushed the AOPS delivery date back to 2018. As with the JSS, the years of delay allowed inflation to hollow out theAOPS budget. A report issued late 2014 by the Parliamentary Budget Officer (PBO) found that the AOPS budget could only afford four vessels at that point. In response, the government added an additional $400 million to the project and revised their official number of ships delivered down to five or six, though these numbers remain optimistic. Inflation has sunk nearly half the proposed AOPS.

$26.2 billion is budgeted to build up to 15 CSCs, at best a one-for-one warship recapitalization program to replace the Royal Canadian Navy’s destroyers and frigate fleet. Given that the AOPS was placed first in the NSPS construction queue, the first CSC will not be delivered for another 10 years with the rest following over a 20–30 year period. This affords inflation plenty of time and opportunity to do its worst. A 2013 PBO report and recent news reports draw attention to this fact, with inflation placing nearly half the future CSC fleet in jeopardy. The financial situation is so grim that, as a cost saving measure, there has even been a proposal to start cannibalizing systems from our current fleet with which to outfit our future fleet.

The thrust of this short piece is that we must stay aware of the negative effects of inflation in our military procurements. Delays come with significant costs. In the cases of the JSS and AOPS, the costs are fewer and less capable ships.

How can inflation be addressed, aside from cutting numbers or capabilities to stay within eroded budgets? The best way is speed, something to keep in mind regarding the CF-18 Replacement Project and proposals by the Opposition parties to restart an open bidding process. Would any benefits that could result from pressing the reset button on that procurement program again outweigh the high costs of additional time and inflation? Similarly, robbing the CF-18 Replacement Project to pay for the CSC Project would only magnify the problems of the Royal Canadian Air Force’s recapitalization due to inflation. However, in the case of the CSC, speed is not an option due its place in the NSPS shipbuilding queue.

The other way to address inflation is to simply buy back time by increasing capital budgets. The Trudeau-era’s Defence Structural Review did this, increasing the military’s capital budgets which led to the purchases of the CF-18s and the Halifax-class frigates in the 1980s. This has historically been something that Canada has been adverse to do but times could be changing. As noted above, the AOPS budget was increased late last year by $400 million despite constraints on across the board federal spending. Additional monies will preserve not just CSC numbers, but their capabilities as well.

Ryan Dean is the winner of the 2015 Canadian Naval Memorial Trust Essay Competition and is a PhD candidate in the Department of Political Science, University of Calgary. (Image courtesy of the Royal Canadian Navy.)