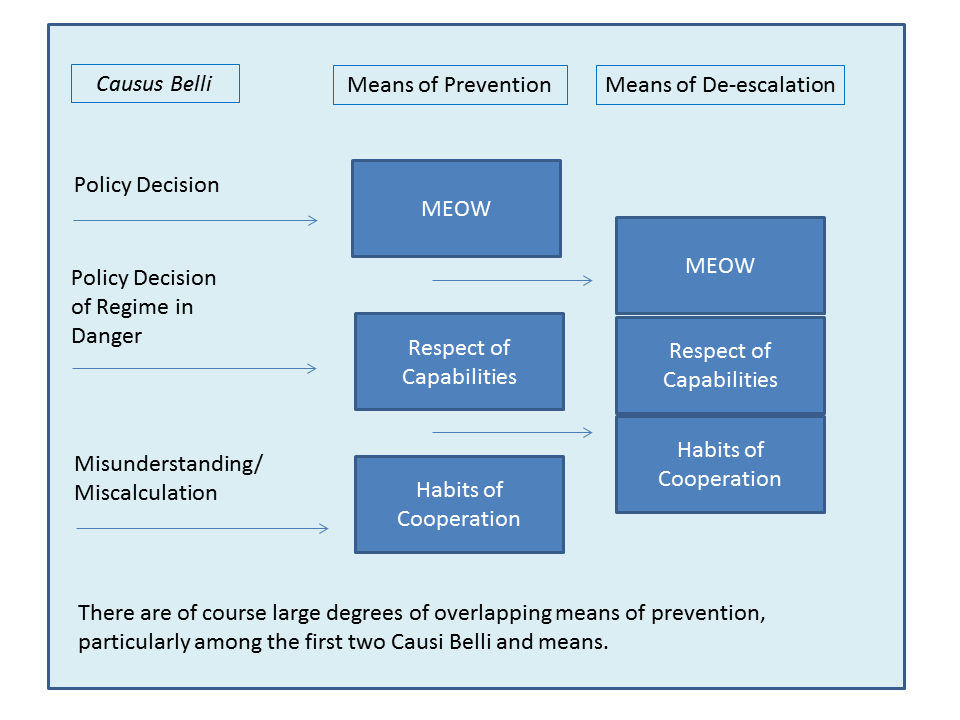

Last summer I wrote two short pieces (Part 1 here; Part 2 here) about preventing conflict between the U.S. and China in the Pacific, or reeling it in should it occur. In the posts I explained why U.S.-Chinese economic interdependence is not enough in itself to prevent the potential start of a conflict that could escalate with disastrous global consequences, or MEOW (Mutual Economic Obliteration – Worldwide).

I noted that the U.S. can take further steps to decrease the likelihood of conflict, and to bolster mechanisms for inhibiting escalating crises – either by sowing respect (often involving means/military capabilities useful in the event prevention fails) or by building “habits of cooperation”.

In part 3 of this series I had intended to lay out a model that could address the need for the second of these lines of effort, by expanded cooperation between the U.S. and Chinese militaries through humanitarian assistance / disaster response (HA/DR) exercises. Clearly, I put off writing too long.

The first thing that has changed is that LCDR Jason Grower called for a very similar approach in April’s Proceedings. I highly recommend reading Jason’s article in its entirety, but in what follows I will outline some of his more important points and highlight where my own thinking differs or builds upon his framework. I will also note where recent developments hold promise of expanded cooperation. Let’s first recap why the U.S. should make the effort.

The Need

In the spring of 2012, my U.S. Naval War College class was split into two teams and told to identify a danger facing the U.S. in the Pacific and develop a plan to mitigate it. Team one took the more “traditional” route, identifying China’s growing military capabilities. Team two looked at the potential second-order perils of regime collapse in North Korea. These hazards included possible blind ‘encounter’ contact between ROK (and/or U.S.) and Chinese forces as they move into to the North to stem refugee flows, secure WMDs, and attempt to stabilize the country.1 More significant than the dangers identified was the fact that the recommended mitigation action – regular HA/DR exercises with China – was roughly the same for both developments, and that both teams arrived at their solution set by following a similar logic.

While much attention has been given to the importance of deterring through strength (“sowing respect”), this primarily prevents conflicts of policy in the event decision makers in Beijing seek to achieve political goals “through other means.” Despite MEOW this is not an impossible scenario, especially in the event of internal power struggles or a PRC regime on the ropes. However, both teams felt that it more likely a conflict would begin out of misunderstanding, mistakes, or the misbehavior of a rogue command or commander – whether in the seas surrounding China or on the Korean Peninsula. Since such an incident would not be prevented through the normal means of MEOW or sowing respect, we therefore turned to the HA/DR exercises as efforts towards building “habits of cooperation,” thought not only “vital to diffusing those instances when misunderstanding and accidents lead to a stand-off with few face-saving options”, but also helpful in de-escalating those conflicts sprung from a different causus belli.

While much attention has been given to the importance of deterring through strength (“sowing respect”), this primarily prevents conflicts of policy in the event decision makers in Beijing seek to achieve political goals “through other means.” Despite MEOW this is not an impossible scenario, especially in the event of internal power struggles or a PRC regime on the ropes. However, both teams felt that it more likely a conflict would begin out of misunderstanding, mistakes, or the misbehavior of a rogue command or commander – whether in the seas surrounding China or on the Korean Peninsula. Since such an incident would not be prevented through the normal means of MEOW or sowing respect, we therefore turned to the HA/DR exercises as efforts towards building “habits of cooperation,” thought not only “vital to diffusing those instances when misunderstanding and accidents lead to a stand-off with few face-saving options”, but also helpful in de-escalating those conflicts sprung from a different causus belli.

In his article, Jason explains the need for the exercises in several ways. Echoing the focus on building “habits of cooperation”, he states one of the primary purposes of such an HA/DR exercise would be to “heighten understanding between the two militaries and promote stable military-to-military relations.” Further, he believes it would provide an opportunity to “bolster broader U.S.-Chinese ties” and even internal Chinese military-civilian ties.

Such ties help the transformation in relationship from what conflict theorist Johan Galtung calls a ‘negative peace’, in which there is no direct violence, to a ‘positive peace’, in which an attitude shift has allowed the development of a cooperative partnership. Yet it’s important to remember that these ties are just one leg of the prevention triad – even the ties of the Union, where future foes sat side-by-side in the same military academies, could not prevent the U.S. Civil War once policy makers had settled on violence.

To his credit, Jason also looks beyond the strategic implications and discusses the direct impact a Sino-American HA/DR exercise on the affected people in the region, by increasing the “global ability to respond to disasters in the Pacific”. Familiarity between U.S. and Chinese counterparts of each other’s capabilities/standard operating procedures in HA/DR operations is particularly important, as their maritime forces are likely to work elbow-to-elbow in same operational spaces of future calamities – whether Korea or Borneo, and coordination can boost the efficacy of the response. After all, as Jason notes, “to the person whose home was decimated and needs medical care quickly, it makes no difference whether the doctors are Chinese, American, or otherwise.”

The Plan

So how would such an exercise look? I had the chance to sit down with Jason two weeks ago over the Pentagon’s finest lunch option (Peruvian chicken!) and we discussed the concept. We agreed that a “conference”, as advocated as the first step in his article, was necessary but pro forma as part of the build-up to a larger exercise or operation, typically referred to as a planning conference.

The first question really is whether to tailor it as an operation, an exercise, or both. Both nations already run their own HA operations – China aboard its Peace Ark, and the U.S. with its annual Pacific Partnership operation – performing medical procedures and building health and first-responder partnership capacities. Pacific Partnership this year is co-led by Australia and New Zealand in addition to the U.S., a set-up that demonstrates scalability, an important attribute given the propensity of China to make its participation contingent upon politically sensitive outcomes (arms sales to Taiwan, meetings with the Dalai Lama). In other words the operation can go on without China if necessary. Further, it allows both the U.S. and China to claim equal leadership, and, if conducted with vessels from each nation, should assuage the moral concerns and intelligence-gathering fears of partners and participating NGOs who might hesitate to join in an operation with China.

Nonetheless, in pursuit of building habits of cooperation2 I believe the U.S. and China would get the most bang for their (fiscally constrained) bucks and yuan through a combined large-scale DR exercise. This could be a capstone event at the tail-end of Pacific Partnership that expands involvement for interested nations and focuses on responding to likely disaster contingencies in the region. While China too recently identified HA/DR as promising common ground for expanded U.S.-China military relations3, it’s a sentiment they’ve expressed in the past and one that has not always borne out. Encouragingly, both the U.S. and China are participating in next month’s ASEAN-led disaster response exercise (ADMM-Plus)4, although the degree of participation and interaction between the two nations is not yet clear.

Still there are additional signs of burgeoning ties, including China’s invitation in January to send for the first time a ship to participate to the 2014 Rim of the Pacific (RIMPAC) naval exercise. Prevention requires more of this. And if China really wanted to show its displeasure with North Korea’s nuclear tests, what better way to do so than participating in a joint HA/DR exercise that either implicitly or explicitly prepared for a post-DPRK Korea?

Scott is a former active duty U.S. Navy Surface Warfare Officer, and the former editor of Surface Warfare magazine. He now serves as an officer in the Navy Reserve and civilian writer/editor at the Pentagon. Scott is a graduate of Georgetown University and the U.S. Naval War College.

Note: The views expressed above are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their governments, militaries, or the Center for International Maritime Security.

1. One solution would be a pre-arranged agreement allowing only ROK troops to move north, or U.S. personnel on a solely humanitarian mission.

2. As well as planning for a post-DPRK Korean Peninsula.

3. And is one of the few areas of military exchange not prohibited by U.S. law.

4. And perhaps just as importantly, Japan.