By Tuan N. Pham

More Chinese assertiveness and unilateralism are coming. In January, this author’s article in a separate publication assessed strategic actions that Beijing will probably undertake in 2018; and forecasted that China will likely further expand its global power and influence through the ambitious Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), expansive military build-up and modernization, assertive foreign policy, and forceful public diplomacy. Recently, three worrying developments have emerged that oblige the United States to further challenge China to become a more responsible global stakeholder that contributes positively to the international system. Otherwise, passivity and acquiescence undermine the new U.S. National Security Strategy; reinforce Beijing’s growing belief that Washington is a declining power; and may further embolden China – a self-perceived rising power – to execute unchallenged and unhindered its strategic roadmap (grand strategy) for national rejuvenation (the Chinese Dream).

Near-Arctic State

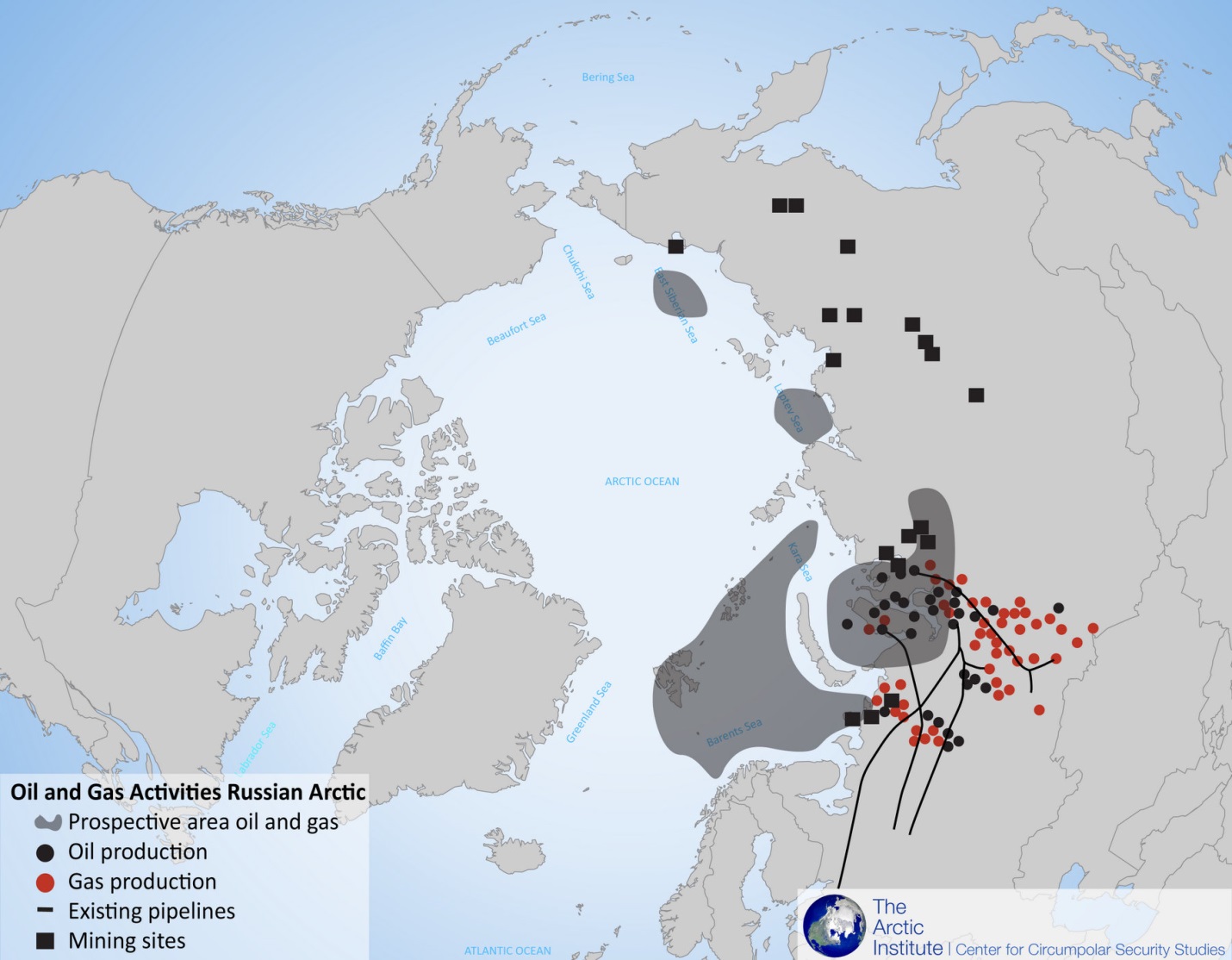

On January 26, Beijing followed up last year’s policy paper “Vision for Maritime Cooperation Under the BRI” that outlined its ambitious plan to advance its developing global sea corridors (blue economic passages connected to the greater Belt and Road network) – with its first white paper on the Arctic. The white paper boldly proclaimed China’s strategic intent to actively partake in Arctic activities as a “near-Arctic state.” Activities include but are not limited to the development of Arctic shipping routes (Polar Silk Road); exploration for and exploitation of oil, gas, mineral, and other material resources; utilization and conservation of fisheries; and promotion of Arctic tourism.

Beijing rationalizes and justifies this expansive political, economic, and legal stance as “the natural conditions of the Arctic and their changes have a direct impact on China’s climate system and ecological environment, and, in turn, on its economic interests in agriculture, forestry, fishery, marine industry, and other sectors.” In other words, China stakes its tenuous Arctic claims on geographic proximity; effects of climate change on the country; expanding cross-regional diplomacy with extant Arctic states; and the broad legal position that although non-Arctic countries are not in a position to claim “territorial sovereignty”, they do have the right to engage in scientific research, navigation, and economic activities. And while vaguely underscoring that it will respect and comply with international law like the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) in a “lawful and rational matter”, Beijing was quite explicit and emphatic in the white paper that it will use Arctic resources to “pursue its own national interests.”

There is no legal or international definition of “near-Arctic state.” China is the sole originator of the term. Beijing is clearly attempting to inject itself into the substance of Arctic dialogue and convince others to accept the self-aggrandizing and self-serving term. Furthermore, as noted by Grant Newsham, the phrase itself is a representative exemplification of how China incrementally and quietly builds concepts, principles, vocabulary, and finally justification for pursuing its national interests and global ambitions. Consider the following evolution that is typical of how key elements of China’s strategic lexicon come to the fore like “near-Artic state and the South China Sea (SCS) has been part of China since ancient times”:

Step 1 – Term appears in an obscure Chinese academic journal

Step 2 – Term appears in a regional Chinese newspaper

Step 3 – Term is used at a Chinese national conference or seminar

Step 4 – Term is used in Chinese authoritative media

Step 5 – Term is used at international conferences and academic exchanges held in China

Step 6 – China frequently refers to the term in foreign media and at international conferences

Step 7 – China issues a policy white paper stating its positions, implied rights, and an implied threat to defend those rights

Step 8 – China maintains that this has always been Beijing’s policy

Beijing’s official policy positions on Antarctica are less clear and coherent, and appear to be still evolving. The closest sort of policy statement was made last year by China’s State Oceanic Administration when it issued a report (pseudo white paper) entitled “China’s Antarctic Activities (Antarctic Business in China).” The report detailed many of Beijing’s scientific activities in the southernmost continent, and vaguely outlined China’s Antarctic strategy and agenda with few specifics. All in all, Beijing doesn’t have a formal claim over Antarctic territory (and the Antarctic Treaty forbids any new claims), but nonetheless, China has incrementally expanded its presence and operations over the years. The Chinese government currently spends more than any other Antarctic state on new infrastructure such as bases, planes, and icebreakers. The expanding presence in Antarctica is embraced by Beijing as a way and means to build the necessary physical fundamentals for China’s Antarctic resource and governance rights.

South “China” Sea

On February 5, released imagery of the Spratly archipelago suggests that China has almost completely transformed their seven occupied reefs – disputed by the other claimants – into substantial Chinese military outposts, in a bid to dominate the contested waters and despite a 2002 agreement with the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) not to change any geographic features in the SCS. At the same time, Beijing has softened the provocative edges of its aggressive militarization with generous pledges of investments to the other claimants and promising talks of an ASEAN framework for negotiating a code of conduct (CoC) for the management of contested claims in the strategic waterway. However, it is becoming increasingly apparent that China is determined to finish its militarization and then present the other claimants with a fait d’accompli before sitting down to negotiate the CoC.

The photographs show that Beijing has developed 72 acres in the SCS in 2017 and over 3200 acres in the past four years; and redirected its efforts from dredging and reclaiming land to building infrastructure (airstrips, helipads, radar and communications facilities, control towers, hangars, etc.) necessary for future deployment of aircraft to project Chinese power across the shipping routes through which trillions of dollars of global trade flows each year. On February 8, China’s Ministry of Defense announced that it recently sent advanced Su-35 fighter aircraft to take part in a joint combat patrol over the SCS.

At the end of the day, these latest images will not change Beijing’s agenda and plans for the SCS. They do however provide a revealing glimpse of what is happening now and what may happen in the near future on these disputed and contested geographic features (rocks and reefs) – and it sure does not look benign and benevolent as China claims.

At the 54th Munich Security Conference from February 16-18, the Chinese delegation participated in an open panel discussion on the SCS and took the opportunity to publicly refute the prevailing conventional interpretation of international maritime law. They troublingly stated for the first known time in an international forum that “the problem now is that some countries unilaterally and wrongly interpreted the freedom of navigation of UNCLOS as the freedom of military operations, which is not the principle set by the UNCLOS.” This may be that long-anticipated policy outgrowth from the brazen militarization of the SCS and the latest regression of the previous legal and diplomatic position that “all countries have unimpeded access to navigation and flight activities in the SCS.” Now that China has the supposed ways and means to secure the strategic lines of communication, Beijing may start incrementally restricting military ships and aircraft operating in its perceived backyard, and then slowly and quietly expand to commercial ships and aircraft transiting the strategic waterway. If so, this will be increasingly problematic as the People’s Liberation Army Navy continues to operate in distant waters and in proximity to other nations’ coastlines. China will then have no choice but to eventually address the legal and diplomatic inconsistency between policy and operations – and either pragmatically adjust its policy or continue to assert its untenable authority to regulate military activities in its claimed exclusive economic zones, in effect a policy of “do as I say, not do as I do.”

In the public diplomacy domain, Beijing is advancing the narrative that Washington no longer dominates the SCS, is to blame for Chinese militarization of the SCS, and is destabilizing the SCS with more provocative moves. On January 22, the Global Times (subsidiary of the People’s Liberation Army’s Daily) published an op-ed article cautioning American policymakers to not be too confident about the U.S. role in the SCS nor too idealistic about how much ASEAN nations will support U.S. policy. Consider the following passage: “For ASEAN countries, it’s much more important to avoid conflicts with Beijing than obtain small favors from Washington. Times are gone when the United States played a predominant role in the SCS. China has exercised restraint against U.S. provocations in the SCS, but there are limits. If the U.S. doesn’t stop its provocations, China will militarize the islands sooner or later. Then Washington will be left with no countermeasure options and suffer complete humiliation.” On February 25, the same state-owned media outlet wrote that “China should install more military facilities, such as radar, aircraft, and more coastguard vessels in the SCS to cope with provocative moves by the United States”; and predicted that the “Sino-U.S. relations will see more disputes this year which will not be limited to SCS, as the United States tries to deal with a rising China.”

On January 17, USS Hopper (DDG-70) conducted a freedom of navigation operation (FONOP) during which it passed within 12nm of Scarborough Shoal. This was the fifth U.S. naval operation in the last six months to challenge China’s excessive maritime claims in the SCS. The Chinese media largely portrayed the operation as the latest in a series of recent U.S. actions intended to signal a new policy shift consistent with the new muscular U.S. National Security Strategy and U.S. National Defense Strategy and reflective of growing U.S. misgivings over China’s rise. The Chinese media is also increasingly depicting Beijing as having the upper hand in the SCS at the expense of rival Washington; and that U.S. FONOPs are now pointless since China has multiple options to effectively respond and there’s very little the United States can do about it.

Sharp Power (Influence Operations) Growing Sharper

In late-January, African Union (AU) officials accused Beijing of electronically bugging its Chinese-built headquarters building, hacking the computer systems, downloading confidential information, and sending the data back to servers in China. A claim that Beijing vehemently denies, calling the investigative report by the Le Monde “ridiculous, preposterous, and groundless…intended to put pressure on relations between Beijing and the African continent.” The fact that the alleged hack remained undisclosed for a year after discovery and the AU publicly refuted the allegation as Western propaganda speaks to China’s dominant relationships with the African states. During an official visit to Beijing shortly after the report’s release, the Chairman of the AU Commission Moussa Faki Mahamat stated “AU is an international political organization that doesn’t process secret defense dossiers…AU is an administration and I don’t see what interest there is to China to offer up a building of this type and then to spy.” Not surprisingly, Fakit received assurances from his Chinese counterpart afterwards on five key areas of future AU-China cooperation – capacity building, infrastructure construction, peace and security, public health and disease prevention, and tourism and aviation.

The suspected hack underscores the high risk that African nations take in allowing Chinese information technology companies such prominent roles in developing their nascent telecommunications backbones. The AU has since put new cybersecurity measures in place, and predictably declined Beijing’s offer to configure its new servers. Additionally, if the report is true, more than just the AU may have been compromised. Other government buildings were constructed by China throughout the African continent. Beijing signed lucrative contracts to build government buildings in Zimbabwe, Republic of Congo, Egypt, Malawi, Seychelles, Guinea-Bissau, Lesotho, and Sierra Leone.

On January 23, President Xi Jinping presided over a Chinese Communist Party (CCP) leading group meeting to discuss how better to deepen the overall reform of the central government. He emphasized that 2018 will be the first year to implement the spirit of last year’s 19th National Party Congress and the 40th anniversary of China’s opening up to the West and integration into the global economy. The meeting reviewed and approved several resolutions (policy documents) to include the “Guiding Opinions on Promoting the Reform and Development of Confucius Institute.” The new policy synchronized the promotion of reform and development of the Confucius Institute; and directed both to focus on the “building of a powerful socialist country with Chinese characteristics, serving Beijing’s major powers diplomacy with Chinese characteristics, deepening the reform and innovation, improving the institutional mechanisms, optimizing the distribution structure, strengthening the building efforts, and improving the quality of education” – so as to let the latter (Confucius Institute) become an important force of communication between China and foreign countries.

The seemingly benign and benevolent Confucius Institute is quite controversial, and is now receiving greater scrutiny within the various host countries for covertly influencing public opinions in advancement of Chinese national interests. In the United States, FBI Director Christopher Wray announced on February 23 that his agency is taking “investigative steps” regarding the Confucius Institutes, which operate at more than 100 American colleges and universities. These Chinese government-funded centers allegedly teach a whitewashed version of China, and serve as outposts of Beijing’s overseas intelligence network.

On February 17, Xi issued a directive to cultivate greater support amongst the estimated 60 million-strong Chinese diaspora. He called for “closely uniting” with overseas Chinese in support of the Chinese Dream, as part of the greater efforts and activities of the United Front – a CCP organization designed to build broad-based domestic and international political coalitions to achieve party objectives. He stressed that “to realize the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation, we must work together with our sons and daughters at home and abroad…It is an important task for the party and the state to unite the vast number of overseas Chinese and returned overseas Chinese and their families in the country and play their positive role in the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation.” Ultimately, he hopes these overseas Chinese will collectively cooperate to counter political foes of the CCP, advance the party’s political agenda, and help realize broader Chinese geo-economic ambitions such as the BRI.

Conclusion

The aforementioned troubling and destabilizing developments egregiously challenge the rules-based global order and U.S. global influence. Like China’s illegal seizure of Scarborough Shoal in 2012 and Beijing’s blatant disregard for the landmark ruling by the International Tribunal of the Permanent Court of Arbitration in 2016, they further erode the trust and confidence in the international rule of law (and norms) and undermine America’s traditional role as the guarantor of the global economy and provider of regional security, stability, and leadership. If the international community and the United States do not push back now, Beijing may become even more emboldened and accelerate the pace of its deliberate march toward regional and global preeminence unchallenged and unhindered.

Tuan Pham has extensive experience in the Indo-Pacific, and is widely published in national security affairs and international relations. The views expressed therein are his own and do not reflect the official policy or position of the U.S. Government.

Featured Image: Chinese President Xi Jinping addresses the annual high-level general debate of the 70th session of the United Nations General Assembly at the UN headquarters in New York, the United States, Sept. 28, 2015. (Xinhua/Pang Xinglei)