Asia’s maritime arms race has again highlighted the emerging relevance of aircraft carriers. China, India and Japan made significant progress with their flattops. As all major powers in the region run for more and larger carriers, the question is: Who is ahead?

Japan

First of all, Tokyo, please stop these ridiculous wordplays. Carriers are carriers and not “helicopter destroyers”, no matter what official spokespersons are saying. Back in the Cold War, nobody believed the Soviet’s heavy flight deck cruisers were actually “cruisers”.

First of all, Tokyo, please stop these ridiculous wordplays. Carriers are carriers and not “helicopter destroyers”, no matter what official spokespersons are saying. Back in the Cold War, nobody believed the Soviet’s heavy flight deck cruisers were actually “cruisers”.

Japan’s present fleet includes two Hyuga-Class and one Izumo-Class helicopter carriers (CVH). Lacking a well deck, they have no amphibious role and are only able to operate helicopters or fixed wing aircraft. Such helicopters can either be used for any number of missions, from Search and Rescue (SAR), surface warfare (SUW), anti-submarine warfare (ASW), or troop movements. Moreover, purchasing some V-22 Ospreys is another option for Japan. Recent maneuvers with the US Navy showed, V-22s are able to operate from the Hyugas.

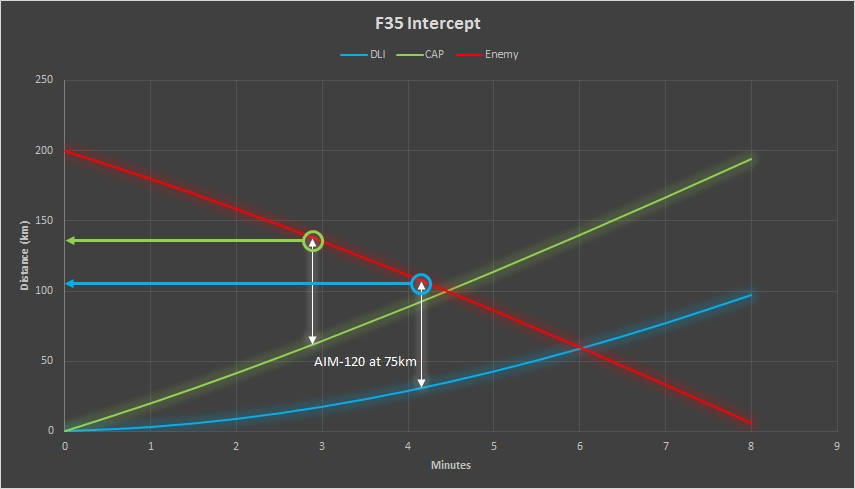

The main issue is whether Japan’s CVH can operate fixed wing STOVL aircraft, in particular Lockheed’s F-35B (STOVL – Short Take-off and Vertical Landing). Japan’s three CVH are not yet ready to host F-35B, though they could easily be converted into smaller carriers to operate V/STOL aircraft. Due to “no obvious technical obstacles“, the only issue left is the political decision.

The the F-35B has been critiqued for the poor performance of its STOVL variant: enormous fuel consumption during takeoff and landing, limited payload, limited range. In the maritime East Asia, distances are not so far that long range would be necessary. The F-35B may be superior to Chinese warplanes as a whole program, because China has presented prototypes rather than a factory-ready mass-produced model of its 5th generation carrier fighters.

Japan’s main obstacle is the complete absence of combat experience since 1945. However, its navy enjoys the opportunity to train with the US and perhaps Britain in the future: countries with proven combat experience. GlobalSecurity.org reports, moreover, that Japan may consider a program for a larger carrier starting in the 2020s. However, there current evidence says that Japan is about to go for STOBAR or CATOBAR carriers. Hence, Japan will play an important role in the carrier arms race. Maybe the F-35B will boost Japanese maritime power, if Tokyo decides to go for it. However, size and nature of Japan’s carrier program will not bring the country into leading position.

South Korea

Seoul’s flattop program is less developed than Japan’s. The South Korean Navy (ROKN) runs one Dokdo-class helicopter carrier and aims to operate three at the end of the decade. Like Japan, these flattops are said only to operate helicopters, but they could be modified to host F-35B. Drones could also be an option. Unlike Japan, the ROKN’s Dokdo has a well deck and can therefore be used for amphibious operations.

Seoul’s flattop program is less developed than Japan’s. The South Korean Navy (ROKN) runs one Dokdo-class helicopter carrier and aims to operate three at the end of the decade. Like Japan, these flattops are said only to operate helicopters, but they could be modified to host F-35B. Drones could also be an option. Unlike Japan, the ROKN’s Dokdo has a well deck and can therefore be used for amphibious operations.

However, even though there are reports about South Korean interests in the F-35B, officially plans for converting the Dokdos into a small carrier have been denied. Such a political move is logical. In the U.S, the F-35B has proved to be a budget disaster and has yet to show its operational capabilities. Fortunately, China has not crossed the threshold of full operational capability; the LIAONING is still relatively green and there are no Chinese indigenous carriers. Seoul has still time to weigh its options.

South Korea will only keep regional military weight if Seoul broadens its pursuit of “blue-water ambitions“. In particular, this means spending much more money on an expeditionary navy to include additional flattops. With its sophisticated shipbuilding industry, South Korea would be able modify the Dokdos to small carriers or develop new indigenous carriers. However, the political consequence would be entrance into the great power competition between the navies of the US, China, India and Japan. The ROKN will definitely not take a lead, but do not count South Korea out. If things in maritime Asia get worse, Seoul made decide to follow the Japanese example.

Australia

The two forthcoming Canberra-Class LHDs would able to operate F-35B. The ski-jump on prow is credible evidence. However, right now Australia has no intention to go for the F-35B. Needless to say, political landscapes can quickly change. We will see what happens in Canberra after the F-35B has proven its operational abilities and the carrier arms race continues. Australia could also operate UAVs from her carriers.

The two forthcoming Canberra-Class LHDs would able to operate F-35B. The ski-jump on prow is credible evidence. However, right now Australia has no intention to go for the F-35B. Needless to say, political landscapes can quickly change. We will see what happens in Canberra after the F-35B has proven its operational abilities and the carrier arms race continues. Australia could also operate UAVs from her carriers.

We will not see high-profile patrols of Australian LHDs in the East and South China Sea. The Royal Australian Navy may use Canberras for joint exercises with the US, Japan, South Korea, or the Philippines. In terms of operations, the use of the LHD will be to underline Australia’s hegemonial role in the Pacific Islands, disaster relief, and potentially in tackling the refugee issue.

Thailand

As long as Thailand does not seriously invest in its single carrier, the Chakri Naruebet will be nothing else than the “Royal Yacht“. Thailand’s carrier rarely operates and the crews have rare practical experience. Do not bet on Thailand. The Thai carrier will only make a difference in disaster relief.

Singapore

Singapore has yet to jump for a flattop. However, due its very limited space for air force bases, the tiny city-state seriously considers an F-35B purchase. In the future, LHD or small Izumo-style carriers could be an option for Singapore. Basing the fighters offshore would save urgently needed space on land. Nevertheless, there is no credible evidence yet that Singapore is really planning to buy warships like the Izumo (if anybody comes across news regarding this issue, please drop me a line). Thus, Singapore remains a known unknown. What would make Singaporean carrier very relevant is its geographic location close to Malacca Strait and southern end of the South China Sea.

Russia

From the four Mistral LHDs Russia’s navy is about to commission, two will be based in the Pacific. There are no indications that Russia is planning to develop a new STOVL aircraft, although the country’s industry would be capable of doing so (Yak-38, YAK-141). Thus, the Mistrals will only be outfitted with helicopters and, therefore, not make a significant difference in the Indo-Pacific’s maritime balance of power.

Moreover, it cannot be ruled out that Russia use the new LHDs in waters other than the Pacific. Recently, the Russian Navy deployed warships from its Pacific Fleet to the Mediterranean for a show of force offshore Syria.

New Russian aircraft carriers are only discussed, but far away from being realized. If the Russians would start to build new carriers, they would first replace the aging Kuznetsov and, thereafter, strengthen their Northern Fleet to protect their interests in the Atlantic and Mediterranean.

India

The Indian Navy should definitely be taken into account for a front position. Due to the operational experience of its single operational carrier INS Viraat and its soon to be commissioned two new STOBAR carriers INS Vikramaditya and INS Vikrant, India is now Asia’s number one in maritime aviation. In the 2020’s, an even larger carrier INS Vishal is in the works; perhaps a CATOBAR design, which would provide far better striking capabilities, and maybe even nuclear powered. While future expansion has yet to be determined, in the present India is going to build up a sophisticated three-carrier fleet. The Indian Navy will be able to maintain always one carrier battle group at sea and to project power in the western Pacific.

The Indian Navy should definitely be taken into account for a front position. Due to the operational experience of its single operational carrier INS Viraat and its soon to be commissioned two new STOBAR carriers INS Vikramaditya and INS Vikrant, India is now Asia’s number one in maritime aviation. In the 2020’s, an even larger carrier INS Vishal is in the works; perhaps a CATOBAR design, which would provide far better striking capabilities, and maybe even nuclear powered. While future expansion has yet to be determined, in the present India is going to build up a sophisticated three-carrier fleet. The Indian Navy will be able to maintain always one carrier battle group at sea and to project power in the western Pacific.

However, India lacks access to a carrier-capable 5th generation fighter. There is no carrier-version of Indo-Russian Suchoi PAK FA under development. Joining India’s forces in the early 2020, the PAK FA will only be available as a land based fighter. India’s Mig-29 and the potential Rafale are definitely combat capable aircraft, but surely behind the F-35’s abilities and probably, too, behind China’s J-31. Once other Indo-Pacific powers operate their 5th generation fighters from carriers, India will fall behind in quality if not quantity.

In addition, operating different fighter and carrier models, as India is about to do, increases maintenance costs significantly. Nevertheless, just by the numbers of operational vessels and the operational experience, India will take the lead in Asia’s carrier arms race for this decade and maybe also in the early 2020s, but not longer.

China

As much has been written about China, we keep it brief here. Given China’s “Two-Ocean-Strategy”, seeking to operate always one carrier in the Pacific and Indian Ocean, the PLAN will need up to 5-6 flattops. We have physical evidence now for what everybody knew before: Chinas is commencing an indigenous aircraft carrier program. The hot issue is, for which design China will go. Will they re-build LIAONING‘s STOBAR design? Alternatively, will they go straight for a more advanced CATOBAR design?

As much has been written about China, we keep it brief here. Given China’s “Two-Ocean-Strategy”, seeking to operate always one carrier in the Pacific and Indian Ocean, the PLAN will need up to 5-6 flattops. We have physical evidence now for what everybody knew before: Chinas is commencing an indigenous aircraft carrier program. The hot issue is, for which design China will go. Will they re-build LIAONING‘s STOBAR design? Alternatively, will they go straight for a more advanced CATOBAR design?

Probably the first and second indigenous Chinese carrier will be a conventional powered STOBAR flattop. Thereafter, we may either see conventional or even nuclear powered CATOBAR carriers. Beside military requirements, for political prestige Beijing will not accept its carrier fleet to be behind the level of India. Instead, after the “century of humiliation” China will seek for clear superiority over India, Japan, and other potential Asian naval powers.

Who is ahead?

Right now India is definitely ahead due to operational experience and the number of vessels. Regarding technology, Japan is likely to be number one. However, both will be surpassed by China either at the end of his decade or surely within the 2020s. South Korea, Australia, Thailand, and Singapore are economically too weak to be a maritime game changer. However, it will be interesting to watch how these and other countries are seeking for maritime alliances to balance China. Russia will not play a major role in maritime Asia, especially not with carriers, because its core interests are located elsewhere.

After Obama scrapped US foreign policy almost entirely in the last years, what will a weakened America do in the Indo-Pacific? States like Japan, South Korea, Singapore, and Australia will rely on US security guarantees. However doubts remain as to whether Obama and his successors are willing to deliver should serious conflicts occur. For a clear message to China, the US needs a credible and increased forward presence throughout the Indo-Pacific. Therefore, Washington should leave theaters like the western Indian Ocean and the Mediterranean to the Europeans as much as possible. If necessary, let Europe learn the hard way that in the Indo-Pacific Century, the times of US military bailouts are over and Europe has to do carry its share of the load.

Felix Seidler is a PhD candidate at the Institute for Security Policy, University of Kiel, Germany, and a German security affairs writer. This article appeared in original form at his website, Seidlers Sicherheitspolitik.