There has been much discussion in the past year on the relative merits and disadvantages of Air-Sea battle as a potential strategy or operational concept. Much of the debate has been a comparison between the warfighting options embodied in the Navy/Air Force concept verses those less kinetic choices incorporated in an “offshore control”, blockade situation. The usual opponent for these measures is the People’s Republic of China. Those in favor of these competing concepts rarely “give the potential enemy a vote” and talk more of what their idea could do vice what the opponent’s response might be. China’s own strategic choices ought to play a greater role in the discussion of these competing plans. One of the most surprising outcomes might be a failure on the part of the Chinese to engage with either vision. A review of a historical similarity, and recent Chinese strategic actions might very well suggest that if the United States attempted to have an Air-Sea battle, the People’s Republic could easily choose to not attend the event and still win the war.

This is not the first time that carefully laid plans for war at sea have come to naught. The naval situation in the North Sea throughout the First World War is an excellent example of one side not really needing to do battle in order to gain an advantage. On the outbreak of war in August 1914, many observers assumed there would be a titanic naval battle in the North Sea between the British Royal Navy (RN)’s Grand Fleet and Imperial Germany’s High Seas Fleet for the domination of the Atlantic. Noted American naval theorist Admiral Alfred Thayer Mahan had predicted such an event as the logical result of the conflict of great naval powers. Both navies had planned for a confrontation for many years. They held a ten year naval race in the construction of battleships. German officers spoke of “der tag” (the day) that they would meet and defeat the Royal Navy in battle and the German Kaiser Wilhelm II complained that British Navy charts he observed on a visit to British battleship listed the German fleet as the principal British opponent. When war did come however, the seas were largely silent and no great battle immediately took place. German naval officers may have spoken of an immediate engagement with the RN, but their leadership had a much more nuanced strategy for success.

The Germans wanted to defeat the Royal Navy, but they knew they did not have the numbers to immediately force a decision. Instead they conducted numerous raids in hope of drawing out a portion of the RN they could defeat, and thereby even the odds in a follow-up fleet engagement. They were persistently unsuccessful in doing this, and although there was a brief opportunity at the May 1916 Battle of Jutland to accomplish this goal and destroy the RN’s battle cruiser squadron, the prompt arrival of the bulk of Grand Fleet frustrated these efforts and the German’s beat a sharp retreat for home. Many experts, including such luminaries as Winston Churchill and Admiral Sir John Fisher castigated Grand Fleet Commander Admiral Sir John Jellicoe after the battle for failure to repeat the efforts of the famous Admiral Nelson, who destroyed the combined French and Spanish fleets at the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805.

In reality, Jellicoe had little chance of repeating Trafalgar as the Germans’ strategy did not support the likelihood of a fleet engagement of that magnitude. The German fleet had little reason to come to sea and face annihilation by the British. Its merchant fleets had already been rounded up, and submarines would increasingly become the principle tool for threatening the lines of communication and supply to the British Home islands. All of its vital resources came through protected waters like the Baltic Sea or through overland routes. Although the German surface fleet eventually became demoralized and rebellious after four years of inactivity, hunger, and fanatical disciplinary measures, its basic strategy of “doing nothing” was fully supportable. Admiral Jellicoe could truly have “lost the war in an afternoon” had a significant part of the British fleet been destroyed in battle, but the Germans on the other hand could afford to wait.

China could also afford to wait out any attempts to apply Air-Sea battle just as the Germans did in World War 1. China’s strategic calculations remain open to debate. The Chinese Navy’s leadership may talk boldly about their fleet and its capabilities, but it remains questionable what that fleet might do in wartime. It could be employed in a sudden rush to conquer Taiwan, and then retreat behind the formidable Chinese Anti-Access/Area Denial (A2AD) system. Such a move would leave U.S. naval and air units without a seagoing opponent, but facing potentially high casualties in breaking through shore-based Chinese defenses to aid an occupied Taiwan. Unlike the British in World War 1 whose principle bases were a day’s sail from the potential battleground, a U.S. fleet would need to remain far at sea on station expending fuel, time, and energy waiting for a Chinese naval sorties that might never occur.

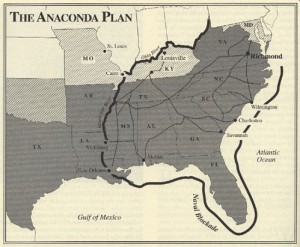

A blockade might be equally fruitless. The Chinese have worked to develop alternative shore-based routes for vital supplies like petroleum products and other basic resources for war. The Chinese govt. has invested large sums of money in the Pakistani port of Gwadar on the Indian Ocean. It signed an agreement with the Pakistani govt. in 2013 to build a 2000 km. long road and rail route from Gwadar to the Chinese city of Kashgar. This route would largely circumvent any U.S. attempts to blockade Chinese fuel imports. The Chinese govt. has also developed friendly relations with Iran and Iranian oil shipped overland to Gwadar would entirely avoid naval blockade efforts. Further Chinese movement of resources and goods for commerce could be conducted through the vast Asian steppes of the Russian republic, another nation with whom China has cultivated an improved relationship. In the early 20th century, British geopolitical theorist Sir Halford Mackinder described this Asian interior as the “heartland” of a future Eurasian economic system. It remains, as it was in Mackinder’s time as largely immune to Western and U.S. military efforts aside from a dwindling U.S. strategic Air Force.

The British Royal Navy desperately desired to engage the German High Seas fleet, and in doing so somehow force an end to the First World War. German strategic thinking made this an unattainable goal. Chinese strategic efforts may equally make both Air-Sea battle and “offshore control” blockades fruitless endeavors. Some commentators have complained that the services’ effort to define these concepts has been slow. This is actually beneficial in that China’s strategic calculus remains nebulous. The usual U.S. methods of creating “strategy” through defense budgets and weapon programs are likely to fail if geography and history are not taken into consideration in planning a U.S. response. The U.S. might plan to conduct Air-Sea battle or an offshore control blockade, but neither would be useful if the Chinese chose not to accept the invitation. The U.S. can no longer deny the opponent their vote in the planning to counter their next move.