Daniel R. Green, In the Warlords’ Shadow: Special Operations Forces, the Afghans, and Their Fight Against the Taliban, Naval Institute Press, 15 July 2017, $29.65, pp. 304

By Patrick Hughes

Introduction

Since the U.S. entered Afghanistan, the question on the minds of civilians, soldiers and commanders alike has been when and how do we leave? A narrative quickly came out of the conventional warfare strategy that boiled down to “shape, clear, hold, build and transition.” Although simple in nature, it was a narrative born out of political necessity and lacked a fundamental understanding of the people that U.S. troops would be fighting and defending. Through In the Warlord’s Shadow, Daniel Green uses experience gained from multiple tours, staggered throughout a decade of conflict, to highlight how this narrative had developed by 2009 when he deployed for the third time. He fades out the major action typically told in conventional war literature and brings out the personal stories of involvement with local leaders. In doing so, Green endorses a balanced war-fighting program that synchronizes development initiatives and tribal outreach with a less kinetic strategy.

Grassroots Counterinsurgency in Action

Although not explicitly mentioned in the book, Green’s candid account stresses several critical flaws in the current thinking behind U.S. counterinsurgency operations. Foremost among these is a misunderstanding of the centers of gravity in insurgency groups. The U.S. military’s understanding of centers of gravity is derived from Carl Clausewitz who defined it as a military’s source of strength. Once these sources are destroyed, the enemy would either be unable or unwilling to effectively sustain combat. However, Green notes that even after “defeating” the Taliban, fighting would recommence shortly after departure. How do you fight an enemy that continues to fight after traditional sources of strength have been depleted? By Green’s account, you sap the strength that they want, but have yet to obtain completely. In the Taliban’s case, this is the will of the Afghan people.

While the reaction to quickly invade Afghanistan was widely considered both moral and justified, the commanders faced a difficult dilemma that more time to plan might have remedied; we knew almost nothing about the political and cultural roots of the conflict. Instead the U.S. entered the conflict viewing the path to victory, and what that would look like, though, as Green calls it, a “prism of their own institutional lens.” We viewed an unconventional conflict as having a conventional end. However, early claims of victory would have to account for a resurgent enemy, continuing U.S. casualties and loss of territory previously thought secure. Deeper understanding of the nature of the conflict would have allowed a strategic narrative to develop along the Afghan cultural mores that the Taliban was exploiting: justice, micropolitics, reconciliation, laissez-faire and village empowerment.

Recounting his experience during a third tour with special operations, Green details how a new strategy, developed along the same mores the Taliban was exploiting, was beginning to work in Afghanistan. He states, “this mission was not exclusively about combat and that one yardstick of [the mission’s] success was getting the Afghans to step up to be part of the solution.” In the original strategy of clear, build and transition, security improved causing local economics to improve, but the community was still not enlisted in its own defense. Although the central government maintained input, the strategy implemented by Green’s unit allowed local tribes to man and manage their defense. This also allowed for economic rebuilding in areas where aid often did not trickle down from the central government. By integrating the locals into improving their own security, Green’s unit effectively turned the Taliban’s “people’s war” against them. Additionally, it contributed to a potential U.S. exit strategy.

Although implemented at the beginning of the 2009 surge, the bottom-up strategy implemented by Green’s unit was noted as having more progress than previous approaches. Perhaps it was only an illusion. Maybe the initial strategies laid key groundwork that allowed for this approach to be effective. However, it logically makes sense that leveraging the Afghan peoples’ will against the Taliban could both simultaneously remove a critical center of gravity and develop an infrastructure that could prevent a resurgence following U.S. withdrawal.

Conclusion

In the Warlord’s Shadow is forthright in its critique of U.S. strategy and highlights areas that we as a U.S. military have room to grow. The most significant lesson from the Afghanistan War is that in fighting insurgency our exit strategy does not stand separate from our entrance strategy, our mid-course operations, or the tactics on the ground. Rather, how we enter and conduct ourselves will dictate how we leave, not the other way around.

In his final redux, Green cautions that the U.S. will only repeat this mistake in the next small war unless we develop an organization willing to challenge the status quo of fighting warfare. We have to develop a bureaucratic culture that has an incentive to use cultural intelligence, diplomacy, and development to create dynamic combat plans. It must retain lessons learned and synchronize approaches between the military and other areas of government influence. Finally, our measures of success cannot come from solely what is done to a local community (i.e. Number of combatants killed), but what comes from it.

ENS Patrick Hughes graduated Summa Cum Laude from Kennesaw State University (KSU) with a BA in International Relations and a BBA in International Business in 2015. Upon acceptance into Navy OCS, ENS Hughes reported to Officer Training Command in Newport, RI November 2015, commissioning early 2016. After commissioning, ENS Hughes reported to Information Warfare Training Command May 2016 where he attended DIVOLC, IWBC and NIOBC. An academic interest in China drew ENS Hughes to select FIAF DT Pearl Harbor as his first duty station where he currently serves at COMPACFLT headquarters.

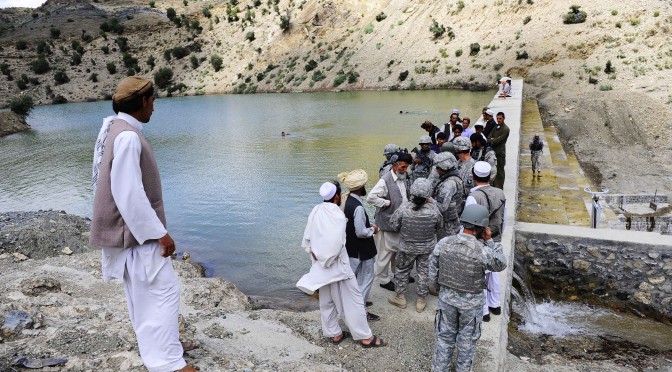

Featured Image: Members of coalition special operations forces meet with Afghan Local Police and Afghan National Army to discuss village stability in the Khakrez district, Kandahar province, Afghanistan, April 19. The ALP, ANA and coalition forces work together to routinely monitor local villages for insurgent activity, ensuring the safety of the local Afghan population. (DoD photo: Petty Officer 2nd Class Gregory N. Juday)