Russia Resurgent Topic Week

By Laguerre Corentin

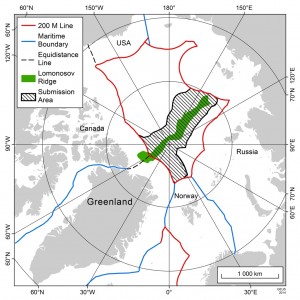

Since the early 2000s, Russia has begun to pay more attention to the Arctic when its general socioeconomic situation had improved.1 With the ice melting, other Arctic and non-Arctic countries demonstrated their interest for the region, creating territorial disputes. In the High North, Russia is often seen as taking an aggressive approach to assert its sovereignty and the West have been worried about Russia’s involvement in the region, especially after the Ukrainian Crisis and the Russian position in Syria. However, is Russia aggressive in the Arctic? We argue that Moscow is likely to promote cooperation with the Arctic states, but with its interests and national security in mind. The Arctic is of strategic importance for Russia because of its natural resources. Indeed, since the end of the Soviet era, Moscow does not see the region as a potential theatre of a strategic struggle with the West. Moreover, in its history, Russia took care to avoid escalating incidents, favoured cooperation, and the respect of international law in the Arctic because it was in its interest. Russia has learned that it could use the law and international organisations to its advantages. Putin’s aggressive tone seems more to fulfil domestic purposes rather than represent Russia’s intentions in the Arctic. To support our thesis it is useful to look at the country’s historical reliance upon legislation and treaties in the region, its current interests, and its emphasis on cooperation in the resolution of disputes.

[otw_shortcode_button href=”https://cimsec.org/buying-cimsec-war-bonds/18115″ size=”medium” icon_position=”right” shape=”round” color_class=”otw-blue”]Donate to CIMSEC![/otw_shortcode_button]

A history of reliance on legislation

Lincoln E. Flake argues that Russia’s current posture on the Continental Shelf is “a natural extension of Tsarist and Early Soviet policies on Arctic land territory”. Russia’s approach to the arctic issues seems to be impacted by previous policies.2 The first experience in claiming land and maritime control in the greater Arctic region occurred in its North American territories with the 1821 Ukase of Alexander I that had both a land and a maritime component. When the neighbouring states rejected the maritime component of the decree, the sole attempt by the Russian government to enforce it was the seizure of the USS Pearl in 1822, but the vessel was released and the maritime component of the decree was abandoned. Each time the Tsarist government tried to enforce a contested decree; it yielded to pressure and abandoned its maritime claims.3 Later, the Soviet government took advantage of treaties to advance its positions. As an example, the 1920 Svalbard treaty assured the Norwegian recognition of the Soviet government. Inadvertently, this treaty was favourable to the USSR by creating a demilitarised zone at the door of its Arctic sector. This event likely demonstrated to the Kremlin that sovereignty issues could be resolved through international treaties to Russia’s advantage. Each time, the authorities used the law to respond to sovereignty issues. Moscow developed a more detailed legislation about its control over the North Sea Route when it was handicapped from preventing foreign military navigation along its Arctic coastline. Moreover, Russia engaged in efforts to arrive at international treaty-based regimes favourable to its claims. This approach led to international conferences that ultimately resulted in the 1982 UNCLOS agreement, which was a resounding victory for Soviet aims in the Arctic.4

Russia’s renewed interests in the Arctic

Today, Russia considers the Arctic as a region of strategic importance for its national security due to the presence of the two-thirds of the Russian sea-based nuclear bases, and the direct access to the Arctic and Atlantic oceans provided by the Kola Peninsula. However, with the end of the Cold War, the region has lost its former military strategic significance as a zone of potential confrontation with the US/NATO.5 Principally, the Arctic is relevant to Russia’s economy and security because Moscow views a prosperous and secure supply of energy as a means of projecting its power in the world. Thus, the Arctic is directly linked to its economic interests. Around 20 percent of its gross domestic product is generated north of the Arctic Circle, as are 20 percent of Russia’s total exports in energy.6 On 18 September 2008, then-President Dmitri Medvedev approved the Foundations of the State Policy of the Russian Federation in the Arctic Up to and Beyond 2020. The document defined the Russian interests in the region – developing the resources in the Arctic, turning the NSR into a unified national transport corridor, maintaining the region as a zone of peace and international cooperation and transforming the Arctic as a “leading strategic resource base”.7 In addition, Russia’s National Security Strategy to 2020, released in May 2009, confirms the importance of the energy sector and connects the country’s success with its status as an energy provider, noting that energy-related issues and regions like the Arctic, the Caspian Sea and Siberia are an important component of its security planning.8

An emphasis on cooperation

In line with the approach developed in the early 2000, the 2013 Concept directs foreign policy to “strengthen Russia’s trade and economic position within the system of world economic relations”, and to use the “capabilities of international and regional economic and financial organisations” to support its economic interests. The Concept shows Russian willingness to work with institutions – particularly the UN – and to be more active internationally. A stated objective of its foreign policy has therefore been to emphasise institutions and issues that elevate its power status. If Putin was critical of Western initiatives and opposed them while employing a more aggressive tone, Russia has committed to more multilateral governance in the Arctic than other countries. Moreover, the Foundations of the State Policy of the Russian Federation in the Arctic for the Period Up to and Beyond 2020 identifies the Arctic as a zone of cooperation. The document asserts Russia’s willingness to work bilaterally and within the framework of regional organisations. Moscow has also taken care not to allow minor skirmishes to escalate.9 These elements balance the plans to extend the Northern fleet’s operational radius and the reinforcement of combat readiness on the Arctic coast. Furthermore, different Russian documents reveal that military security is not a priority, the emphasis being placed on economic concerns. This approach suggests that Russian threat perception is less concerned with strategic confrontation than with challenges to navigational assertions. In this regard, Russian military developments in the Region can be seen as a response to an anxiety over navigational-related interests and not a militarization in anticipation of a struggle over natural resources. Indeed, many of the recent military moves, like the reopening of a Soviet-era base in the Arctic to “ensure the security and effective work of the NSR”, are aligning with the protection of maritime spaces.10 Moreover, Moscow seems more interested to project its power by economic means than military ones because a key source of its power and influence in the world comes from its energy sector. Thus, this reduces the need for an aggressive posture.11

Conclusion

In conclusion, Russia relied on international law and cooperation in the Arctic through different periods of its history. Today, Russia is still a strong supporter of the UNCLOS as a tool to resolve regional disputes and insists upon the scientific basis of its territorial claims. According to Dmitri Trenin, Russia bases its Arctic strategy upon international law and agreements, and its actions in the Arctic may have seemed aggressive in part because they occurred in a context of worsening relations with the West. Russia may oppose Western objectives, but there is a stated commitment to international law and Russia “has shown itself a committed, rule-abiding participant”.12 Moreover, Russia’s current interests in the region do not seem to promote an aggressive posture because they concern principally the economic sector. As 97 percent of the region’s oil and gas deposits are found in undisputed EEZ seabed of littoral states, with the Russian EEZ accounting for 80 percent of the gas, the risk of conflict around natural resources in the High North is likely to remain limited.13

Laguerre Corentin has a M.A. in War Studies from King’s College London and presently works as a research assistant at the Institut de Recherche Stratégique de l’Ecole Militaire (IRSEM), which depends from the French Ministry of Defense.

Read other contributions to Russia Resurgent Topic Week.

[otw_shortcode_button href=”https://cimsec.org/buying-cimsec-war-bonds/18115″ size=”medium” icon_position=”right” shape=”round” color_class=”otw-blue”]Donate to CIMSEC![/otw_shortcode_button]

1 Alexander Sergunin & Valery Konyshev, “Is Russia a Revisionist Military Power in the Arctic?”, Defense & Security Analysis 30:4 (2014), 327

2 Flake, “Forecasting Conflict in the Arctic: the Historical Context of Russia’s Security Intensions”,76-78

3 Idem, 80

4 Idem, 80-82, 86-87

5 Sergunin & Konyshev, “Is Russia a Revisionist Military Power in the Arctic?”, 324, 326

6 Kari Roberts, “Why Russia Will Play By the Rules in the Arctic”, Canadian Foreign Policy Journal 21:2 (2015), 119

7 Sergunin & Konyshev, “Is Russia a Revisionist Military Power in the Arctic?”, 327

8 Roberts, “Why Russia Will Play By the Rules in the Arctic”, 119

9 Idem, 116-119

10 Lincoln E. Flake, “Forecasting Conflict in the Arctic: the Historical Context of Russia’s Security Intensions”, The Journal of Slavic Military Studies 28:1 (2015), 91-92

11 Roberts, “Why Russia Will Play By the Rules in the Arctic”, 116-118

12 Idem, 114, 116

13 Flake, “Forecasting Conflict in the Arctic: the Historical Context of Russia’s Security Intensions”, 89

Bibliography

Flake, Lincoln E. 2015. “Forecasting Conflict in the Arctic: the Historical Context of Russia’s Security Intensions”. The Journal of Slavic Military Studies 28:1, 72-98

Roberts, Kari. 2015. “Why Russia Will Play By the Rules in the Arctic”. Canadian Foreign Policy Journal 21:2, 112-128

Sergunin, Alexander & Konyshev, Valery. 2015. “Is Russia a Revisionist Military Power in the Arctic?”. Defense & Security Analysis 30:4, 323-335

The Russian bear