The following article is part of our cross-posting series with Information Dissemination’s Jon Solomon. It is republished here with the author’s permission. You can read it in its original form here.

Read part one and part two of the series.

By Jon Solomon

Candidate Principle #4: A Network’s Operational Geometry Impacts its Defensibility

Networked warfare is popularly viewed as a fight within cyberspace’s ever-shifting topology. Networks, however, often must use transmission mechanisms beyond physical cables. For field-deployed military forces in particular, data packets must be broadcast as electromagnetic signals through the atmosphere and outer space, or as acoustic signals underwater, in order to connect with a network’s infrastructure. Whereas a belligerent might not be able to directly access or strike this infrastructure for a variety of reasons, intercepting and exploiting a signal as it traverses above or below water is an entirely different matter. The geometry of a transmitted signal’s propagation paths therefore is a critical factor in assessing a network’s defensibility.

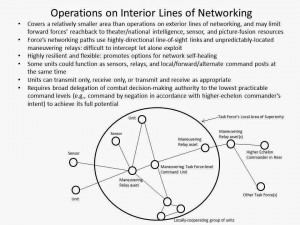

The Jominian terms interior and exterior lines of operations respectively refer to whether a force occupies positions within a ‘circle’ such that its combat actions radiate outwards towards the adversary’s forces, or whether it is positioned outside the ‘circle’ such that its actions converge inwards towards the adversary.[i] Although these terms have traditionally applied solely within the physical domains of war, with some license they are also applicable to cyber-electromagnetic warfare. A force might be said to be operating on interior lines of networking if the platforms, remote sensors, data processing services, launched weapons, and communications relay assets comprising its battle networks are positioned solely within the force’s immediate operating area.

While this area may extend from the seabed to earth orbit, and could easily have a surface footprint measuring in the hundreds of thousands of square miles, it would nonetheless be relatively localized within the scheme of the overall combat zone. If the force employs robustly-layered physical defenses, and especially if its networking lines through the air or water feature highly-directional line-of-sight communications systems where possible or LPI transmission techniques where appropriate, the adversary’s task of positioning assets such that they can reliably discover let alone exploit the force’s electromagnetic or acoustic communications pathways becomes quite difficult. The ideal force operating on interior lines of networking avoids use of space-based data relay assets with predictable orbits and instead relies primarily upon agile, unpredictably-located airborne relays.[ii] CEC and tactical C2 systems whose participants exclusively lie within a maneuvering force’s immediate operating area are examples of tools that enable interior lines of networking.

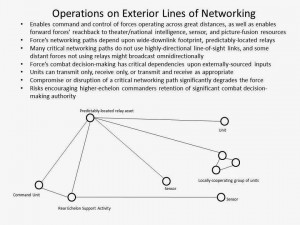

Conversely, a force might be said to be operating on exterior lines of networking if key resources comprising its battle networks are positioned well beyond its immediate operating area.

This can vastly simplify an adversary’s task of positioning cyber-electromagnetic exploitation assets. For example, the lines of communication linking a field-deployed force with distant entities often rely upon fixed or predictably-positioned relay assets with extremely wide surface footprints. Similarly, those that connect the force with rear-echelon entities generally require connections to fixed-location networking infrastructure on land or under the sea. Theater-level C2 systems, national or theater-level sensor systems, intelligence ‘reachback’ support systems, remotely-located data fusion systems, and rear echelon logistical services that directly tap into field-deployed assets’ systems in order to provide remote-monitoring/troubleshooting support are examples of resources available to a force operating on exterior lines of networking.

Clearly, no force can fully foreswear operating on exterior lines of networking in favor of operating solely on interior lines.[iii] A force’s tasks combined with its minimum needs for external support preclude this; some tactical-level tasks such as theater ballistic missile defense depend upon direct inputs from national/theater-level sensors and C2 systems. A force operating on interior lines of networking may also have less ‘battle information’ available to it, not to mention fewer processing resources available for digesting this information, than a force operating on exterior lines of networking.

Nevertheless, any added capabilities provided by operating on exterior lines of networking must be traded off against the increased cyber-electromagnetic risks inherent in doing so. There consequently must be an extremely compelling justification for each individual connection between a force and external resources, especially if a proposed connection touches critical combat system or ‘engineering plant’ systems. Any connections authorized with external resources must be subjected to a continuous, disciplined cyber-electromagnetic risk management process that dictates the allowable circumstances for the connection’s use and the methods that must be implemented to protect against its exploitation. This is not merely a concern about fending off ‘live penetration’ of a network, as an ill-considered connection might alternatively be used as a channel for routing a ‘kill signal’ to a preinstalled ‘logic bomb’ residing deep within some critical system, or for malware to automatically and covertly exfiltrate data to an adversary’s intelligence collectors. An external connection does not even need to be between a critical and a non-critical system to be dangerous; operational security depends greatly upon preventing sensitive information that contains or implies a unit or force’s geolocation, scheme of maneuver, and combat readiness from leaking out via networked logistical support services. Most notably, it must be understood that exterior lines of networking are more likely than interior lines to be disrupted or compromised when most needed while a force is operating under cyber-electromagnetic opposition. The timing and duration of a force’s use of exterior lines of networking accordingly should be strictly minimized, and it might often be more advantageous to pass up the capabilities provided by external connectivity in favor of increasing a force’s chances at avoiding detection or cyber-electromagnetic exploitation.

Candidate Principle #5: Network Degradation in Combat, While Certain, Can be Managed

The four previous candidate principles’ chief significance is that no network, and few sensor or communications systems, will be able to sustain peak operability within an opposed cyber-electromagnetic environment. Impacts may be lessened by employing network-enhanced vice network-dependent system architectures, carefully weighing a force’s connections with (or dependencies upon) external entities, and implementation of doctrinal, tactical, and technical cyber-electromagnetic counter-countermeasures. Network and system degradation will nonetheless be a reality, and there is no analytical justification for assuming peacetime degrees of situational awareness accuracy or force control surety will last long beyond a war’s outbreak.

There is a big difference, though, between degrading and destroying a network. The beauty of a decently-architected network is that lopping off certain key nodes may severely degrade its capabilities, but as long as some nodes survive—and especially if they can combine their individual capabilities constructively via surviving communications pathways as well as backup or ‘workaround’ processes—the network will retain some non-dismissible degree of functionality. Take Iraq’s nationwide integrated air defense system during the first Gulf War, for example. Although its C2 nodes absorbed devastating attacks, it was able to sustain some localized effectiveness in a few areas of the country up through the war’s end. What’s more, U.S. forces could never completely sever this network’s communications pathways; in some cases the Iraqis succeeded in reconstituting damaged nodes.[iv] Similarly, U.S. Department of Defense force interoperability assessments overseen by the Director of Operational Test and Evaluation during Fiscal Year 2013 indicated that operators were frequently able to develop ‘workarounds’ when their information systems and networks experienced disruptions, and that mission accomplishment ultimately did not suffer as a result. A price was paid, though, in “increased operator workloads, increased errors, and slowed mission performance.”[v]

This illustrates the idea that a system or network can degrade gracefully; that is, retain residual capabilities ‘good enough,’ if only under narrow conditions, to significantly affect an opponent’s operations and tactics. Certain hardware and software design attributes including architectural redundancy, physical and virtual partitioning of critical from non-critical functions (with far stricter scrutiny over supply chains and components performed for the former), and implementation of hardened and aggressively tested ‘safe modes’ systems can fail into to restore a minimum set of critical functions support graceful degradation. The same is true with inclusion of ‘war reserve’ functionality in systems, use of a constantly-shifting network topology, availability of ‘out-of-band’ pathways for communicating mission-critical data, and incorporation of robust jamming identification and suppression/cancellation capabilities. All of these system and network design features can help a force can fight-through cyber-electromagnetic attack. Personnel training (and standards enforcement) with respect to basic cyber-electromagnetic hygiene will also figure immensely in this regard. Rigorous training aimed at developing crews’ abilities to quickly recognize, evaluate, and then recover from attacks (including suspected network-exploitations by adversary intelligence collectors) will accordingly be vital. All the same, graceful degradation is not an absolute good, as an opponent will assuredly exploit the resultant ‘spottier’ situational awareness or C2 regardless of whether it is protracted or brief.

In the series finale, we assess the psychological effects of cyber-electromagnetic attacks and then conclude with a look at the candidate principles’ implications for maritime warfare.

Jon Solomon is a Senior Systems and Technology Analyst at Systems Planning and Analysis, Inc. in Alexandria, VA. He can be reached at jfsolo107@gmail.com. The views expressed herein are solely those of the author and are presented in his personal capacity on his own initiative. They do not reflect the official positions of Systems Planning and Analysis, Inc. and to the author’s knowledge do not reflect the policies or positions of the U.S. Department of Defense, any U.S. armed service, or any other U.S. Government agency. These views have not been coordinated with, and are not offered in the interest of, Systems Planning and Analysis, Inc. or any of its customers.

[i] “Joint Publication 5-0: Joint Operational Planning.” (Washington, D.C.: Joint Chiefs of Staff, 2011), III-27.

[ii] For an excellent technical discussion on the trade-offs between electronic protection/communications security on one side and data throughput/system expense on the other, see Cote, 31, 58-59. For a good technical summary of highly-directional line-of sight radio frequency communications systems, see Tom Schlosser. “Technical Report 1719: Potential for Navy Use of Microwave and Millimeter Line-of-Sight Communications.” (San Diego: Naval Command, Control and Ocean Surveillance Center, RDT&E Division, September 1996), accessed 10/15/14, www.dtic.mil/cgi-bin/GetTRDoc?AD=ADA318338

[iii] Note the discussion on this issue in “Joint Operational Access Concept, Version 1.0.” (Washington, D.C.: Joint Chiefs of Staff, 17 January 2012), 36-37.

[iv] Michael R. Gordon and LGEN Bernard E. Trainor, USMC (Ret). The Generals’ War: The Inside Story of the Conflict in the Gulf. (Boston: Back Bay Books, 1995), 256–57.

[v] “FY13 Annual Report: Information Assurance (IA) and Interoperability (IOP),” 330, 332-333.

[vi] See 1. Jonathan F. Solomon. “Cyberdeterrence between Nation-States: Plausible Strategy or a Pipe Dream?” Strategic Studies Quarterly 5, No. 1 (Spring 2011), Part II (online version): 21-22, accessed 12/13/13, http://www.au.af.mil/au/ssq/2011/spring/solomon.pdf; 2. “FY12 Annual Report: Information Assurance (IA) and Interoperability (IOP),” 307-311; 3. “FY13 Annual Report: Information Assurance (IA) and Interoperability (IOP),” 330, 332-334.