By LCDR Christopher Nelson, USN

If chess titles were appropriate, then Dr. Philip Sabin would certainly fall somewhere in the upper pantheon of wargamers. A Professor of Strategic Studies in the Department of War Studies at King’s College London, Dr. Sabin is a gamer, a game designer, and a teacher with over thirty years of experience showing others how wargaming has practical use for military planning.

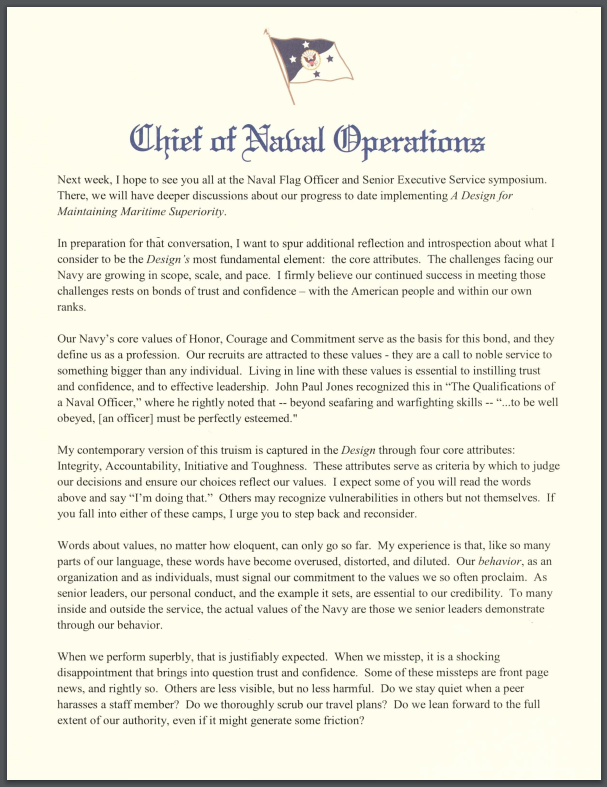

His new book, Simulating War, has a lot going for it. In his book, he talks about the history of wargaming, how to develop wargames, what works and what doesn’t, why wargames are an important part of military planning, and much more.

We had the chance to talk in detail about his book, wargaming, and what got him started many years ago.

Prof. Sabin, welcome. Thanks for taking the time to talk with us about wargaming and your new book, Simulating War. What got you started in wargames?

When I was a child, like many children of that era, I collected toy soldiers and invented games with them. And then, I think I was about twelve years old, and at school a friend of mine had this book called Battle! Practical Wargaming by Charles Grant. This book was a revelation — the idea that you could have rules and do more than simply knock the soldiers down. I remember borrowing the book and copying all the rules overnight. That was the initial thing that got me started.

What do you think wargames can teach us about war?

Let me go back to my childhood experiences. Having started with this game about World War II tactical battles, I soon discovered there were other sets of rules out there for that period and other periods. In particular, there was a group of rules writers in Britain in the 60s and 70s called the Wargames Research Group. This group was made up of army veterans – they knew what war was about. There was one particular game I played with their rules, a competition game, so it actually counted for something. My opposing player had set out his line, and I decided I was going to go for a clever tactic. So I had half my force opposing his main line, while the other half went around a neighboring wood. I was going to try to encircle him. I thought I was the greatest general in history.

Unfortunately, that was when I discovered Clausewitzian friction. You see, going around the wood took a long time. And then I got bogged down in skirmishing when trying to encircle the enemy. In short, my wonderful, clever plan fell apart because my holding force was overwhelmed before my turning force got there. So I realized it is not as simple as having a really clever plan. You have to think about “keep it simple stupid.” Think about the time factor rather than just arrows on a map. Those sorts of lessons really showed me the potential of wargaming.

What advice would you give military planners when wargaming?

Funnily enough I was talking to one of my research students last night about this very issue. He is doing his research on how armies use wargaming. Wargaming is often just done by going for the simplest, most accessible approach. The idea that you would use rules or dice is seen as silly. And in effect, it becomes “let’s just talk about the plan.” I think the key thing is to move beyond simple discussion of a plan to the explicit articulation of an active opponent. Now, already there is the concept of red teaming. And basically that is ‘what if the enemy does this? Well then, OK, we’ll use our reserves to counter, and so on.’ That is certainly better than congratulating yourself as I was doing when I had my forces going around the wood.

The problem with red teaming is that it is disconnected. In reality, the enemy faces the same planning challenges your own force does. They need to come up with a coherent plan. They have to think about the dilemmas they face. One of the most important differences between wargaming and red teaming is that in wargaming you have someone playing the opposing side and trying to win. This is crucial. They are not just the loyal opposition going through the motions. They are really trying to beat you. And they’ve faced the dilemma that they have the same force, space, and time constraints as you do, but within that they have the freedom to operate. The opposing side will be really pleased if they win, but in fact it’s good if they win because it’s a wargame — it’s not reality. It’s very important that if you are going to have something go badly wrong, it is better for that to happen before you do the real thing and people are dying. That’s the most important component: to have enemies who are trying to win and who are thinking separately from your own side.

Let me give you one illustration how this really became clear to me. This is from a project I worked on with the British Army. It was a two sided game. Two forces were playing against one another, and one of them was using British forces and set up a textbook ambush. They had the killing zone laid out, they had their holding forces ready, they had some tanks hidden in the wood ready to come in on the flank, and they were just waiting for the enemy to come into the killing zone where the decisive blow would be struck. And so they waited. Then they asked “Where is he?” and “Why is he not coming?” And then they realized, “Oh no! He is on the flank!” That really brought out that the enemy has a very important vote. That is where wargaming comes in.

There are all sorts of mechanical issues that arise — whether to use dice, and so on. But frankly those are second order issues compared to having a team playing the opponent and trying to win. Red needs to be constrained, they can’t suddenly use forces in places that they don’t have them. But it is through wargaming a situation several times that you get a sense of the variety. A wargame is not an exercise. When you take troops out and you want to make sure they all get the training value, there needs to be a scripted element to it. But a wargame mustn’t be scripted, because that destroys the whole point of it. And you mustn’t use your magical powers to restore things. For example, when the Japanese were wargaming the Battle of Midway, some of their carriers got sunk, and they said that would never happen, so they revived them. But of course, when they lost them for real, they couldn’t magically revive them — they weren’t Gods anymore.

What do you think makes a really good wargame? Is it the number of players for example? Or is it the simplicity of the game? Something else?

I don’t think it is defined by parameters such as the number of players or the playing time, important as those are. I think the basis of a good board game or wargame is that it involves the players and gets them deciding things. It faces them with dilemmas. If players can clearly see what they need to do, well then they are just going through the motions. Wargames come to life when there are real choices, and the best strategies are far from obvious.

The balance between skill and luck, and the involvement of the players, are crucial. With multiplayer games, it is very much about diplomatic skills and trying to make sure that you don’t appear to be the winner until you eventually appear as such. With two players, though, you can can get at some other important elements of the contest, because war is often a bilateral contest. How do you overcome an opponent in what is essentially a zero sum game? There are plenty of contests in which that is the dynamic, the interaction between two dynamic opponents. So two players is just as good as three, it’s just a different experience.

It is important to point out that you don’t even need two players. For a wargame as opposed to an abstract board game, one of the most interesting things is to model and capture the dynamics of an operation. In fact, single players can get a lot of fulfillment out of a wargame, by playing each side in turn. There is little point in playing a game like chess against yourself, since it is just an abstract symmetrical game. But with an asymmetric, realistic wargame, just studying and understanding the dynamics of military operations that are facing both sides can be enormously instructive. So, it does really help if the game can be played with one person. And many wargames are played solo as a matter of course — people may still learn a great deal from them.

What are the advantages of playing a wargame on a board or a map and on a table rather than, let’s say, playing a game on a computer?

There was a perception until recently that board games in general had died out. Everything, people believed, was going the way of video games, computer games, that sort of thing. But that of course is not true — board games are very much coming back in all these different areas. I think there are a number of reasons for this.

One of them is that, although the computer has incredible graphics, the appearance and the feel of a manual game can be superior. For example, you can glance at a map and you can see the whole thing. You can also focus in where you choose and see the details. On a computer screen you tend to have one or the other: you can zoom in or you can see the whole picture, but you can’t have the best of both worlds. With a board game it feels better, it’s tactile, players are talking to one another and looking at one another. They aren’t looking at a computer screen all the time. It’s much more social than playing a computer game.

Next, board games are independent of technology. You don’t have the problem of getting lots of computers to run them or finding the game no longer runs because you don’t have the right Windows operating system. You can pick up board games that were made fifty years ago, and they will play just as well as they did when they were new. You can’t do that with computer games that are even ten years old.

Board games are also cheap — certainly when you consider all the infrastructure that is required for computer gaming. Computer games tend to be built on a mass market principle. There are enormously successful computer games, like “Call of Duty” for example, but they are built for the millions because otherwise they couldn’t make their money back. Therefore they have to be first and foremost entertainment products. And if entertainment collides with realism, then entertainment wins, just as it does in Hollywood for the same reasons. However, in board games you can get them printed in the hundreds and still just about break even. This means you can have more realistic games, because you can design for a niche audience that is interested in realism rather than an audience that is interested in blasting pixels representing Germans or aliens or whatever it might be.

You’ve also got the openness of the board game system. A computer game is like a black box. You might be able to play it easily, but you can’t see what’s making it tick — you can’t see what rules are working behind the scenes. Now, a board game is all there openly for you. You have to engage with it, you have to learn the rules, and as you learn the rules you can see if you agree with them or not. Board games also don’t have the same luxury as computer games that you can cram in everything. Computer games will revel in every round tracked, every single meal a soldier eats, etc., because a computer can. However, that does not necessarily mean it is realistic. Board game designers, because they need to keep things simple enough to be played, need to focus to determine what really matters. They ask: What can we abstract out? This is significant, because when humans analyze the world we need to abstract in order to prioritize. Board game designers can’t just throw everything in and hope the product is going to be realistic.

Finally and decisively, I think, is adaptability. You can look at a board game and see if you agree with it or not. If it is going wrong, you can see where it is going wrong. Students in my MA course are not just playing games that others have designed – they are designing their own games. As soon as you play a game, very often you’ll find something wrong with the game. If so, you can write your own section of the rules and tweak it and play it. Once you have done that a few times, you are moving towards designing your own game. So it’s adaptable, far, far more than a computer game.

What are the top five board games you would recommend to any military planner and why?

This is a difficult question for several reasons. First of all, I want to lay out why it is a hard question, even though there are literally tens of thousands of boardgames out there. It’s hard to make recommendations of this kind. Let me just run through some of the problems. One is accessibility. Unless planners are already wargamers, they will find the ones that have already been published completely inaccessible because they will be too complex for them. That’s one issue.

The second reason it is difficult to answer is that military planners tend to be focused on the most recent past and the future. Most of the board games that have been published — especially the good ones — are not about the most recent conflicts. The same, of course, goes for the great majority of books about war – they cover conflicts which are receding inexorably into the past.

The third issue is interest. It depends who the military planners are and what service they are in and what they are most thinking about. That of course will shape what games are most useful to them. Now, I do have a few suggestions, but please take into account the caveats I have outlined.

I think planners need to start with something simple. And it’s precisely for this reason that I wrote my book Simulating War. In the book there are games that can be played easily, particularly for people that have never played a wargame. So I would suggest that people start simple. It can be a game that takes fifteen minutes. Some of the things I talk about in Simulating War capture nicely the key elements of wargames. For instance, do you reinforce success or do you try and rescue failure? Those sort of classic military dilemmas are encapsulated even in simple games.

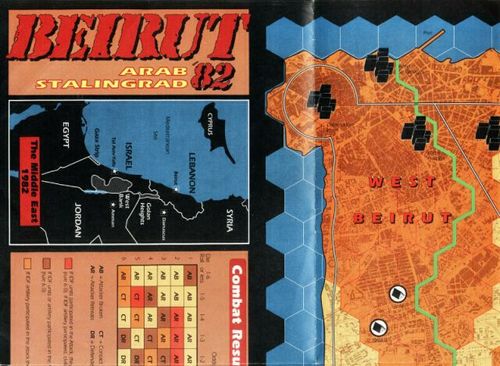

Now moving on from that, I’ll mention some recent games that focus on asymmetric contests, to show that wargames are not necessarily about big generic fights against matched symmetric opponents. One is “Beirut ’82” by Tom Kane. It was published in the late 1980s. It beautifully captures the problem for the Israelis: that they can overwhelm the PLO, but doing so by using massive fire power in the city would mean a political defeat. It is one of the early games that show the balance of military force against political constraints.

Joe Miranda has produced quite a number of games on recent conflicts. There are hits and misses. One of them that is quite interesting is called “Drive on Baghdad.” It’s about the 2003 invasion of Iraq. In that game you are having to balance political and military concerns as well. For example, what sort of resources are you going to use when they are not unlimited? How far are you going to focus on special forces? Or how far are you going to use conventional ground power? And how do these forces interact together against an outmatched opponent — but nevertheless one that is capable of unpredictable reactions?

Brian Train is a good designer who has designed a number of games on recent conflicts. One that I think would be interesting for people to look at is his game on “Kandahar.” It focuses on the challenge of fighting in a counterinsurgency environment in which there are multiple interests. It’s a two player game, but interestingly, the coalition forces are forces that are to be brought in and manipulated, rather than being under direct player control.

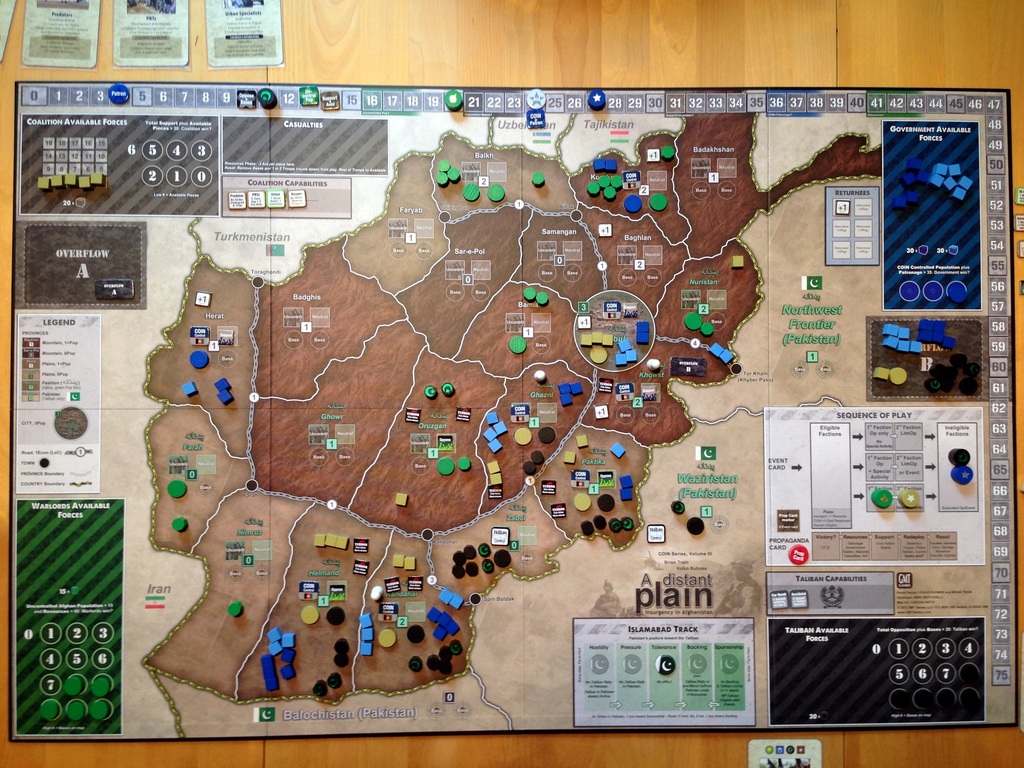

The final thing I recommend is that people have a look at some multiplayer games. The principle of multiplayer games is more important than the game you choose. If you want a multiplayer game that’s relevant to contemporary conflict, then you might want to look at “A Distant Plain.” It’s one of a series on counterinsurgency. It’s a little bit complex and abstract, but the interaction between the four factions is at the heart of the game, and there are artificial intelligence rules to allow fewer live players if desired.

What are your favorite top five games you enjoy playing?

Again, this is a surprisingly difficult question to answer. You might think, ‘Hey, I’m a wargaming professor, so I spend my time playing games.’ But in fact I don’t. I have limited time, so I don’t get to play much. And when I have the time, I tend to be designing rather than playing. Also, when I do play games, I have a tendency to be overly critical. So when I play I tend to be put off easily if I find problems in the gameplay or the research. There are, however, a couple of games that are well worth returning to. One is a game that came out recently from a Finnish game company. It’s called W1815. It literally allows two players to refight the Battle of Waterloo in fifteen minutes. It does it by some extremely clever abstractions, like not moving forces on the map, but still having the historical options to reinforce here or to attack there based upon some clever use of cards. I really like that game as a case study in breaking away from the idea that wargames have to be complex.

There’s a game designed by John Butterfield which I’ve played a lot. It’s called “RAF.” It’s a solitaire game about the Battle of Britain. You are the Royal Air Force, deploying your forces to counter an overwhelming but ill-informed Luftwaffe attack. It is in those sorts of situations that solitaire games work quite well, because when you have a two player game on the Battle of Britain, the Germans tend to know too much because of hindsight. Any variant of Butterfield’s game is a good one, but my own favorite is his “Hardest Days” version which focuses on individual days of the Battle.

It may sound terribly immodest, but since I find so many published games to be inaccurate, over-complex or both, I tend to spend at least as much time playing my own designs such as “Hell’s Gate,” which try to overcome both of these deficiencies. My “Lost Battles” game includes scenarios for three dozen different ancient battles, and I have probably played this game more often over the years than all other wargames put together.

Over at War on the Rocks, Dr. James Lacey wrote a piece on how he uses wargaming in the classroom. A few others, to include the U.S. Secretary of Defense, have been vocal proponents of wargaming. In your opinion, do you think there is a resurgence in wargaming?

Wargaming has always been a cyclical thing. Peter Perla has written very eloquently about this. Sometimes there are good times and sometimes there are bad times. It tends to go in cycles of a decade or two. This is just the latest upsurge. We are hoping we can make hay while the sun shines. Why should it be happening at this particular moment? I think there are a number of reasons. One is the pervasiveness of gaming within modern society. So much of our leisure time is spent playing games. It may be something like Angry Birds or a first-person shooter, or indeed board games that are being used in education. Wargaming is benefiting from the upsurge in “gamification” in society and it is no longer being seen as a childish thing. The idea that one plays games is no longer enough to damn one, because so many people are doing it.

Another reason is strategic uncertainty. We are now in a post-Iraq and Afghanistan position where it is not clear what the next crisis or the next war will involve. We need to be prepared for a wider range of contingencies. Wargaming — including historical wargaming — hence comes back into its own. Because if you don’t know what the future holds, then you need to learn about warfare generically, and that includes historical war, because it gives you a sense of the overall phenomenon. This will help to prepare you for the unknown future.

Additionally, I think a very powerful reason, which you can see working twenty or thirty years ago as well, is that wargaming tends to flourish most when we have suffered a bloody nose. It’s interesting that the great flowering of American wargaming was in the 1970s. That was in the aftermath of Vietnam. When you realize that “Hey, we are not that good, we are not that clever, we don’t seem to be able to win,” you start to see how you might be able to do better in the future. A lot of future success, then, comes out of wargaming as a direct response to the frustrations of Vietnam. I think you are seeing some similar responses now. We have had great frustrations with some of our recent conflicts. People are saying “We are clearly not getting it right.” It is interesting to note that the Germans, as the losers in World War One, put much more effort into wargaming in the inter-war years, which paid off for them in the early years of World War Two.

What websites or magazines are good tools for someone who wants to explore wargaming or determine what games might be suited for their purposes?

I would start, in terms of websites, with a website called ConsimWorld.com. That website has a whole range of articles and links and reviews and so on, which will allow people — really starting from nothing — to get a flavor for this whole area. Then of course, there is boardgamegeek.com. BoardGameGeek is incredibly comprehensive. If I want to find out a particular wargame, I simply type in the name of the wargame and “bgg.” It will immediately bring up the wargame with reviews and pictures and more. It is much more comprehensive than ConsimWorld. But as I said, I would start with ConsimWorld. Another place I would check out is grognard.com. This site serves as an introductory resource, similar to ConsimWorld. For computer wargames I would check out wargamer.com.

In terms of magazines, the best option, despite its small circulation, is called “Battles Magazine.” It is published in France, but in English. There is a game in each issue. It comes out every six months or so. It is a very good compilation of reviews and theoretical discussion about board wargaming, and is the best publication even though it is largely unknown. There is also a number of American magazines. Most of them contain more or less superficial discussions on military topics, accompanied by a wargame. However, “Against the Odds” is a magazine that is worth looking into. If you want to know about games published over the last forty or fifty years, there was a review magazine called “Fire & Movement” which is no longer being published, but which contains good coverage of past wargames within its 150 issue run. Hopefully they will digitize this collection for people to go back and have a look.

You published your own commercial wargame, a game called “Hells Gate.” Can you tell us about the process of creating and publishing a wargame?

As in a number of the games I’ve created, the process started with me playing other peoples’ games on this battle (the Korsun pocket on the eastern front in early 1944), and finding them deficient in various ways and ripe for tweaking and amendment. There are actually some good books on this battle by scholars like Glantz and Zetterling, so as my research developed I eventually got to the point where I thought I could design my own game from scratch rather than just tweaking other people’s designs. So that was the genesis of the game.

Now originally I didn’t design “Hells Gate” to be a part of my courses. I designed it because I was interested in this battle. The design process itself, on and off, took about three months. But it was very much on and off. The way that wargame design tends to work is that you keep notes and you tend to jot down notes whenever ideas occur. Then it is a matter of lots of iterative playtesting interspersed with further rules tweaks until finally a playable and historically sound game emerges.

Once the game was ready, I realized that it was just about simple and accessible enough to use in class to illustrate the dynamics of maneuver and encirclement which I discuss in earlier lectures. Hence, I created some large scale components, and gradually built up to the current situation where I have six simultaneous games being run by teaching assistants for four or five students each. I also included Hell’s Gate as one of the several games in my Simulating War book. The final step in the process was when Victory Point Games suggested publication of a free-standing edition with professional graphics and components, which has proved very successful with the wider hobbyist community.

Because CIMSEC is a maritime focused organization, what games would you recommend to our readers that are interested in historical maritime battles at sea?

It depends on whether people are interested in the tactical or the strategic. One game I would recommend is Ben Knight’s old magazine game “Victory at Midway.” It is a double blind game, in which neither side knows where the enemy is. It is a contest of blind man’s bluff, like the original Kriegsspiel. It also nicely shows the logistics and the challenges with launching and recovering carrier airstrikes and handling that in the face of limited information. It is a good one to start out with.

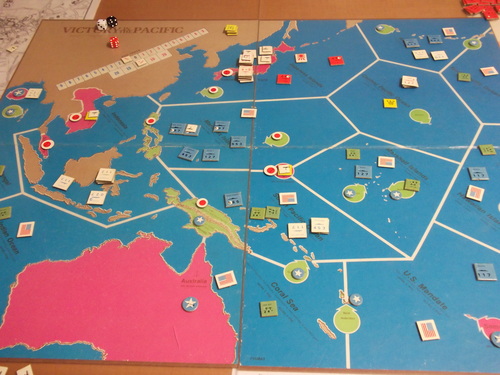

If you are interested in the big strategic picture — especially the greatest naval war that has ever been, the Pacific War — you can do a lot worse than a game by Avalon Hill called “Victory in the Pacific.” There you will be fighting effectively the entire naval war in the Pacific: a huge naval war with large amounts of attrition.

There was an interesting game of contemporary naval combat called “Seastrike,” first published back in the 1970s by the Wargames Research Group. Here you are focused on the creation of small naval task forces. There is a very telling element of constrained resources. You can put together almost any type of task group you want — you can even design your own vessels. But of course everything has a price tag attached. ‘Ok, you want to have a better anti-missile defense system?’ That’s fine, you can. But here’s the bill: It means you won’t get as much air support or whatever.’ It is a very nice planning game in terms of showing us the tradeoffs in a constrained resource environment.

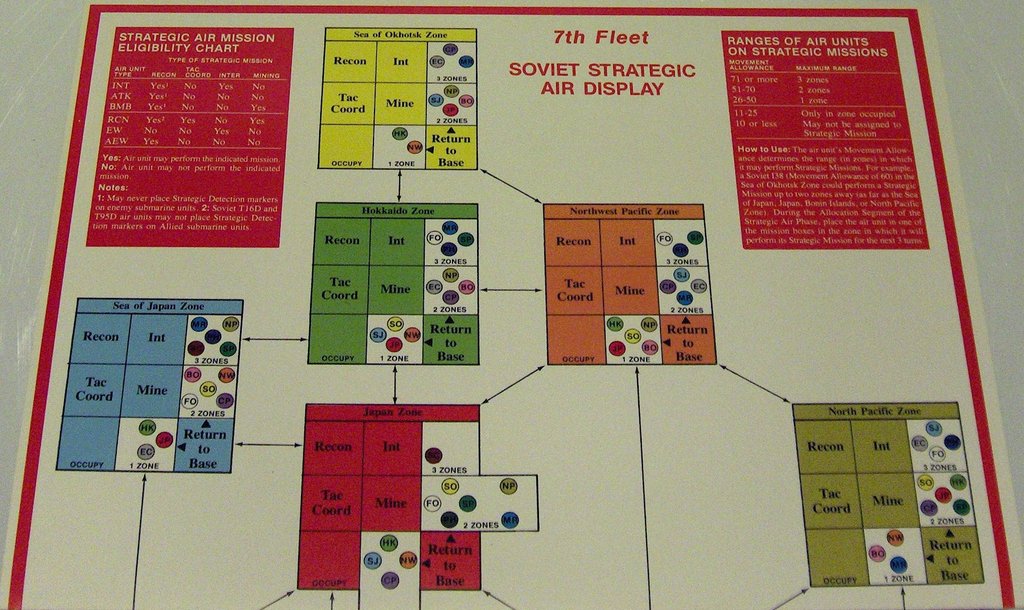

Moving gradually towards the present, there is a series by Victory Games called the “Fleet Series.” It was published in the 1980s, so it is focused very much on a U.S. v. Soviet context. It is very interesting in terms of accessibly handling the complex interaction of air and naval and subsurface forces. There have been more recent games, but they tend to go over the top in terms of complexity. So for an operational perspective, I would recommend one of the “Fleet Series” games.

Finally, there is now a computer game which is in essence the successor to the famous “Harpoon” series of board and computer games. It is called “Command Modern Naval and Air Operations.” Rather than recommending just board games, I would suggest you have a look at that, published a year or two ago. You won’t be able to modify it the same way you can a board game, but the computer can handle some of the details that would be a bit overpowering in a board game.

Prof. Phil Sabin, thank you for stopping by to chat, I thoroughly enjoyed it.

Thank you.

Philip Sabin is Professor of Strategic Studies in the Department of War Studies at King’s College London. He has worked closely with the UK military for many years, especially through the University of London Military Education Committee, the Chief of the Air Staff’s Air Power Workshop, and KCL’s academic links with the Defence Academy and the Royal College of Defence Studies. Professor Sabin’s current research and teaching involves strategic and tactical analysis of conflict dynamics from ancient to modern times. He makes extensive use of conflict simulation techniques to model the dynamics of various conflicts, and for thirteen years he has taught a highly innovative MA option module in which students design their own simulations of past conflicts. He has written or edited 15 books and monographs and several dozen chapters and articles on a wide variety of military topics, including nuclear strategy, British defence policy and air power. His recent books Lost Battles (2007) and Simulating War (2012) both make major contributions to the scholarly application of conflict simulation techniques. He has just completed a contract for the British Army’s Centre for Historical Analysis and Conflict Research to design a Camberley Kriegsspiel with which officers may practise battlegroup tactics. Professor Sabin undertakes many other activities in the conflict simulation field, including co-organising the annual ‘Connections UK’ conference at KCL for over a hundred wargames professionals. He has appeared frequently on radio and television, and has given many dozens of lectures and conference addresses around the world.

LCDR Christopher Nelson, USN, is a regular contributor to CIMSEC. On most days you’ll find him with a book in his hands. The comments above are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect those of the US Department of Defense or the US Navy.

Featured Image: The author H. G. Wells playing a wargame with W. Britain toy soldiers according to the rules of Little Wars. Wells is using a piece of string cut to a set length of the distance his soldiers can move. An umpire sits in a chair with his stopwatch timing Wells. Wells’ opponent waits for his turn to move and fire his cannon at Wells’ soldiers. (HG Wells)