Part I examined the military implications of China’s continued “military” actions versus Japan in the East China Sea or the United States and other countries in the South China Sea if China were to establish an ADIZ. Part II examines whether China has real economic or trade leverage to force other countries, including the United States, to support its point of view regarding the ruling. Part II also analyzes the related question of whether there are costs to China from continuing to ignore the legal ruling and ways in which China can be legally compelled to comply.

By Mark E. Rosen

Embargoes and Sanctions

Shortly after the Tribunal ruling, China’s Deputy Minister of Trade was careful to encourage Chinese citizens to not boycott the U.S. and the Philippines; however, that does not mean that sanctions and boycotts are off the table. Bloomberg reported on August 4th that China will likely resume trade retaliation tactics against South Korea for its decision to deploy U.S. THAAD missiles to counter North Korean missile launches. Korea’s International Trade Association has identified 26 measures currently in place to restrict trade and is expecting more non-tariff barriers such as bogus safety inspections of inbound products, establishment of new licensing requirements, and manipulation of quarantine and safety inspections to frustrate Korean imports.

The above actions are not unprecedented. In 2000, China banned all imports of South Korean mobile phones and polyethylene in retaliation for Seoul’s increase of duties on Chinese Garlic. In 2010, Chinese Customs Officials halted the shipments of rare earth minerals destined for Japan (for user in hybrid cars, wind turbines and guided missiles) as a form of protest for detention of a Chinese fisherman fishing near the Senkakus. The United States has also been victimized by China’s extensive unfair trade practices (dumping and illegal subsidies), theft of intellectual property, and hacking of U.S. companies. Working within the WTO system, the U.S. has filed a record number of suits versus China in the WTO on behalf of U.S. poultry producers and is now considering the unilateral institution of a total ban on Chinese steel imports because of illegal price fixing and other illegal actions by Chinese steel producers.

The use of non-tariff barriers has been a favorite ploy by countries to sneakily frustrate imports to protect local producers while at the same time staying compliant with WTO rules. As for embargoes, WTO (Art 21) recognizes that states can impose measured national security, health, and welfare controls on both exports and imports to protect their citizens’ “essential security interests” or to prevent the proliferation of weapons. Using this exception, China passed a new national security law in 2015 which required foreign technology companies to be “secure and controllable” by Chinese National Security Agencies as a way of pushing out foreign technology firms like Microsoft, Apple, and Cisco in favor of local suppliers. However, there are limits to this type of activity, as witnessed in the 1998 Shrimp Turtle Decision in which a WTO Panel found that a U.S. ban on shrimp from India, Malaysia, Thailand and Pakistan (because those states shrimp fishermen had allegedly killed Sea Turtles) was illegal because controls can only be used to immediately protect one’s own citizens from harm. Controls cannot be used to “send signals” or indirectly pressure an exporting state to reform.

In the short term, China has considerable legal room to maneuver should it wish to impose national security controls or erect non-tariff barriers to punish Japan, the United States, the Philippines, and others for opposing them in maritime disputes. WTO cases are very time consuming to document and litigate. However, that same legal maneuver space can also be exploited by the United States and others to frustrate Chinese imports. Therefore, China should do the math and assess whether they have more to gain or lose by instituting de facto embargoes.

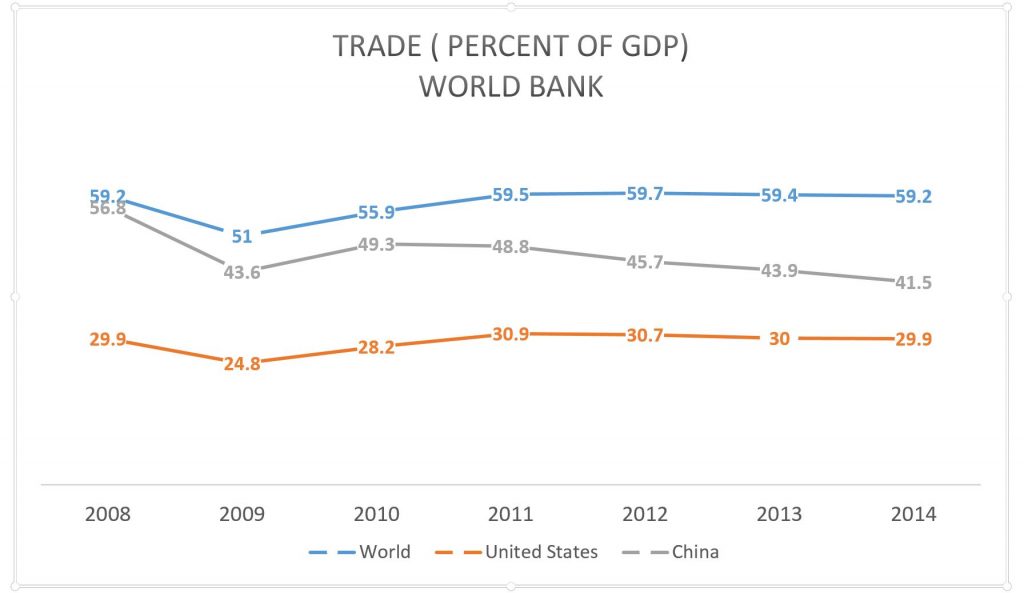

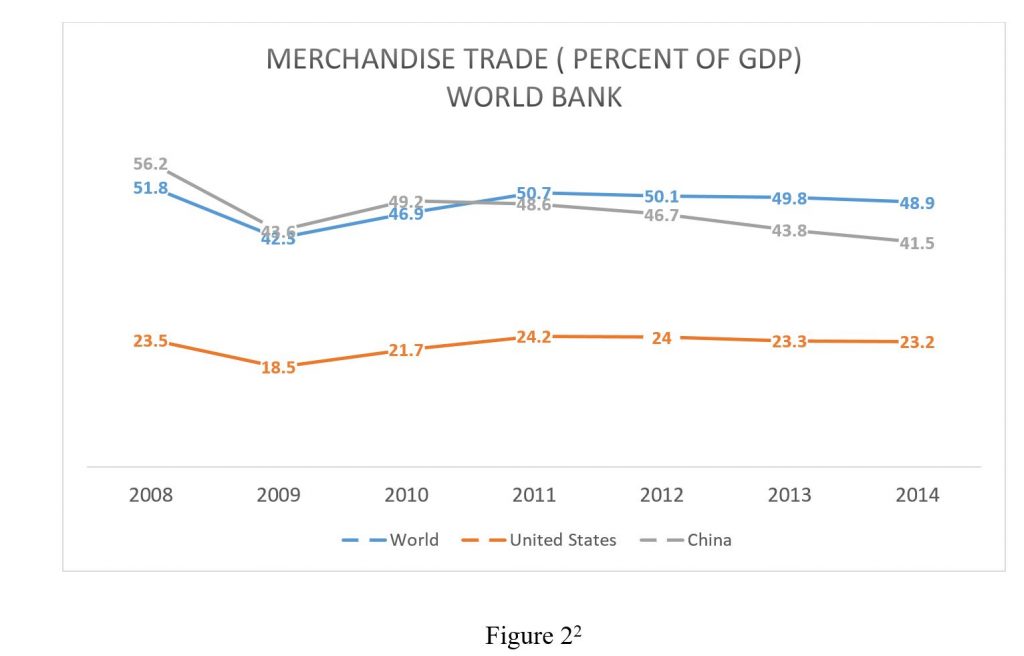

In 2015, China amassed a $365 billion merchandise trade surplus with the United States. Chinese businesses have put this cash to good use by investing in new plants and equipment, educating its young people abroad, and investing billions in the U.S. and other safe offshore markets. This is not unique to the U.S.; China has a global trade surplus of $600 billion. It continues to have small trade deficits with Japan and South Korea and its principal imports are electrical and industrial machinery (no. 1 and 3), oil (no. 2), and ores (no. 4). This cursory analysis of China’s economy overwhelmingly demonstrates that China is highly dependent on international trade to fuel its economy. China’s offshore investments of its U.S. trade surplus helps China diversity its holdings outside of Asia. China is also heavily reliant on international suppliers for the raw materials it lacks and risks a great deal by starting a trade war in which it is deprived access to the U.S. and other foreign markets.

History confirms that China would likely suffer more than the U.S. or Japan, Australia, and the Philippines as a result of an embargo. Tough Allied embargoes against Nazi Germany and Italy proved ineffective when self-interest among allied business interests caused the embargoes to leak or, in the case of Germany, forced innovation when Germany developed synthetic substitutes for oil and other commodities. When the U.S. embargoed wheat exports to the USSR in 1973, Canada and Australia picked up the business. The latter is especially important in the current situation. If China were to stop buying Australian ore or Japanese finished products, the world economy is sufficiently diverse to compensate for some of these losses. After the U.S. embargoed exports of scrap iron, steel, and oil to Japan and froze Japan’s assets, Japan was put into the position of having to choose between fighting for additional raw materials or abandoning their plans for a “New Order” in Asia. It is unlikely that any country would launch a Pearl Harbor attack if China were to embargo their products; however, embargoes have a high potential for “blowback” and could result in unintended consequences to the PRC’s overseas businesses, mines, and industrial operations.

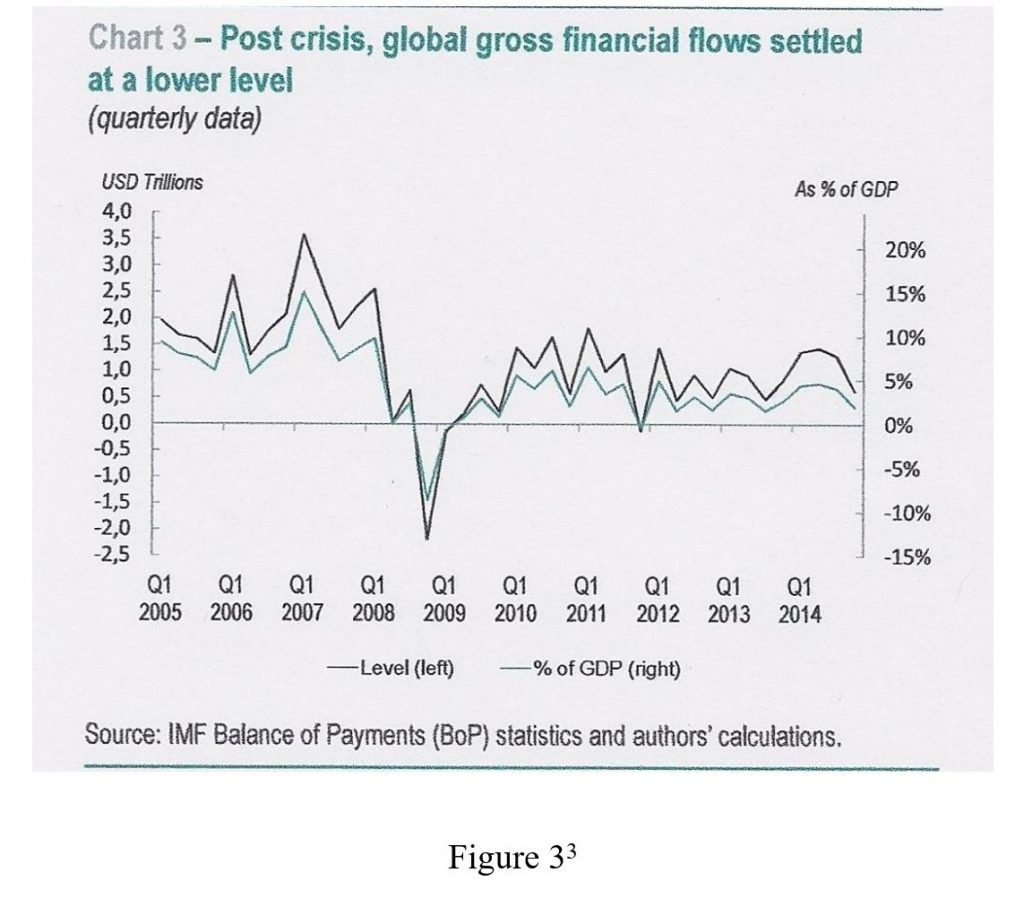

It is also fiction that the U.S. is vulnerable to Chinese action because of its stake in the U.S. public debt (20% foreign owned). In reality, China buys U.S. sovereign debt because it is safe, liquid and can be used by China to finance dollar denominated international transactions (such as oil). China’s central bank also buys U.S. sovereign debt to maintain the exchange rates for renminbi and help drive down the costs of Chinese exports. Also, U.S. sovereign debt is overwhelmingly held by U.S. domestic entities (66%); such that were China to dump its nearly $1 trillion in U.S. debt, that debt will simply be purchased by domestic and foreign purchasers – as happened in August 2015 when China reduced its U.S. debt holdings by $180 billion. For China, the impact of “a broad scale dump of U.S Treasuries…would be that China would actually export fewer goods to the United States.”

Sanctions and embargos tend to “leak” because the global market will almost always produce another supplier or purchaser of something that is being withheld from the international market. Philippine bananas and mangos also taste good in Tokyo, Paris, and New York. Given China’s extreme dependence on international trade to fuel its domestic growth and overseas investment, it would be almost suicidal for China to engage in actions that might restrict its access to foreign markets. Likewise, a government-lead boycott of foreign products would, apart from the legal repercussions, would have extremely destructive impacts on its economy since it still relies heavily on imports of agricultural products, industrial equipment (from mostly Japan and Korea), and metal ores for manufacturing applications. Finally, dumping U.S. debt might cause some angst but, in the long run, U.S. debt instruments would be purchased by investors in the U.S. and other countries.

Continued Trashing of the Tribunal Decision and International Law in General

China continues to condemn the Tribunal ruling. The traditional attacks focused on questions of lack of jurisdiction and “overstepping” its legal mandate. Another Chinese daily’s reported that the Tribunal was a “front” for the United States and “lackey” of outside forces and had an inherent bias because the Philippines paid the “court costs” for the proceeding. A few speculated that China might withdraw from UNCLOS, but China will more likely establish its own arbitral panel to adjudicate the territorial disputes outside of UNCLOS. This later course of action has precedent; recall China’s 2015 establishment of an Asian Infrastructure Bank to finance Asian infrastructure projects outside of the regulation-burdened World Bank system.

China seems to labor under the perception that the Tribunal Ruling is purely a regional matter and that its impacts end with the states bordering the SCS. China continues to ignore that many countries take the ruling very seriously because the SCS is a maritime superhighway between the Middle East, South Asia, East Africa, North Asia, and Australia. Roughly 60 percent of South Korea’s energy supplies, nearly 60 percent of Japan’s and Taiwan’s energy supplies, and 80 percent of China’s crude oil imports come through the South China Sea. According to a 2015 report from the Council of Foreign Relations:

“Each year, $5.3 trillion of trade passes through the South China Sea; U.S. trade accounts for $1.2 trillion of this total. Should a crisis occur, the diversion of cargo ships to other routes would harm regional economies as a result of an increase in insurance rates and longer transits.”

Money talks. For this reason, states that would ordinarily have been silent registered their support for the Tribunal decision. The EU issued a statement on July 15, underscoring their support for a rules-based order and respect for UNCLOS. The G-7 called on states to “fully implement decisions binding on them in … tribunals under the Convention.” Canada, France, Germany, the UK, Japan, Vietnam, Singapore and the U.S. issued statements support of the ruling. Indonesia, India, South Korea issued more “measured” statements urging China to show restraint and respect for UNCLOS.

There were some dissenters, but much of the industrial world supported the outcome and expects China to comply. If China continues to signal that it has no interest in conforming to the ruling, China could be excluded from important international negotiations, including, for example, the upcoming negotiation of an agreement under UNCLOS that deals with biodiversity beyond national EEZs. As I suggested in After The South China Sea Arbitration, China could have its privileges essentially suspended in three UNCLOS institutions: (1) the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea (ITLOS); (2) the International Seabed Authority (ISA), and the (3) the Commissions on the Limits of the Continental Shelf (CLCS).

If China continues its island-building activities and interferes with Philippine fishing in the vicinity of Second Thomas Shoal, Scarborough Shoal, and Mischief Reef, an international court such as the International Court of Justice (ICJ) or ITLOS, could be asked to impose sanctions on the China for flaunting a lawful UNCLOS decision. The case would be predicated on the notion that China cannot take advantage of the benefits of UNCLOS if it lives outside of the law. In practical terms, an injunction could be sought which: recalls China’s judge on ITLOS; blocks the CLCS from any further proceedings involving the Continental Shelf entitlements of China; and lastly suspends both China’s ability to file further deep-seabed mining applications before the ISA and enjoin any further prospecting of its sites in the Indian Ocean. It might also be appropriate for a Tribunal to suspend China’s participation in UNCLOS related bodies including the International Seabed Authority (ISBA) (which writes the regulations for deep seabed mining), the International Hydrographic Organization (IHO) (the charting and oceanography body) and the International Maritime Organization (IMO). The latter action would be especially harmful for China given that the IMO has broad responsibilities to write the rules for merchant ship design, construction, operations, and navigational routes/practices while China has one of the largest merchant marine fleets in the world.

These legal maneuvers would be slow to orchestrate but, like other types of sanctions, could be far-reaching and difficult to reverse once they are put in place. However, China’s continued island reclamation after the ruling, their recent military actions in the vicinity of Scarborough Shoal, and the Chinese Supreme Court’s reaffirmation of the 2012 fishing ban are in direct contravention of the Tribunal’s decision. Since the effects of China’s actions have impacts beyond the Philippines, almost any bordering state, international organization, or possibly NGO would have standing to seek to have the Tribunal’s decision enforced since the ICJ (and for that matter ITLOS) has “inherent jurisdiction…to ensure that its exercise of jurisdiction is not frustrated and that its basic judicial functions are safeguarded.”

Conclusion

Inexorably, China is painting itself into a corner in which its escape options become more limited. While it was hoped by officials in the U.S. and elsewhere that China would eventually come to the realization that it needed to capitalize on the favorable aspects of the ruling and “pivot” on those it did not like, that is not happening. The recent military displays in the ECS and SCS, the threatened sanctions towards South Korea, and continued “trashing” of the Tribunal ruling suggest that China is opting for confrontation versus conciliation and now runs the risk of becoming involved in a major military conflict with Japan and perhaps the United States. China says that it is committed to a rules-based order and leadership in Asia but its recent actions say otherwise. Lastly, and perhaps most importantly, pursuit of high risk strategies which could place China’s international trading relations at risk is antithetical to the Chinese Community Party’s 13th Five Year Plan for 2016-2020 to promote balanced international trade, inbound investment, and free trade zones.

It is entirely possible that China’s leadership does not fully appreciate the dangerous choices their countrymen are making and how their actions are being perceived on the world stage. Military-to-military encounters at sea are occurring on a daily basis, and the potential for a costly misstep increases with each passing day. So too, a miscalculation in the trade or economic arena would likely backfire since China is a trading nation and it can ill afford to have its products excluded from foreign markets. High-level diplomacy and cool heads should be the order of the day.

A maritime and international lawyer, Mark E. Rosen is the SVP and General Counsel of CNA and holds an adjunct faculty appointment at George Washington School of Law. The views expressed in this paper are those of the author alone and do not represent the views of CNA or any of its sponsors.

Featured Image: Triple-E class container ship “Madison Maersk” of Maersk Line loaded with containers is berthed at Nansha port in Guangzhou. (Reuters)