By Corentin Laguerre

Russia’s latest military doctrine, published in January 2015, has generated a great amount of discussion, especially because it named NATO as the primary security threat faced by the Russian Federation. If NATO has always been considered as a potential threat by Russia, this document is different in tone. Indeed, NATO is identified as a “fundamental external threat” and global rivalry is considered as the key driver of international politics, rather than international cooperation as it was the case in the past.1 Despite its original objective to counter the USSR, little in NATO policy or strategy can be seen as directly threatening Russia.2 In regards to the Ukrainian conflict and to the increasing tension between NATO and Russia, in order to avoid further escalation or a “New Cold War”, it is necessary to understand why Russia’s hostility toward NATO has increased since the 90s. Our hypothesis is that Russia is hostile to NATO because of its vision of international relations as a zero-sum game. This view makes the Alliance and its military capabilities threatening to Russia’s security and status. Moreover, this vision is reinforced by Russia’s return to its -Cold war mythology and a will to defend its traditional values against those represented by NATO. Finally, combined together these elements are pushing Moscow to balance NATO’s power in Russia’s traditional sphere of influence, thus increasing the phenomenon of security dilemma by pushing the Alliance to take steps to reassure its members, which reinforces Russia’s hostility. In a first part, the article will explore the origins of Russia’s threat perception of NATO, then it will argue that the deeper reason of Russia’s hostility is a difference of values, and finally, it will present the consequences of this hostility in the light of Stephen Walt’s balance of threat theory.

NATO as a Threat Source

The Russian Federation has always been skeptical about the objectives of the Alliance and the possibility to cooperate with it, even if they both share common interests. Indeed, since the end of the Cold War, Russia believes that its security environment has worsened due to an unstable neighbourhood, the expansion of NATO, and the Alliance’s missile defense program.

This skepticism comes from the fact that Russia follows the principles of realpolitik, considers that the use of force is still present in international affairs and that international relations are a zero-sum game. Thus, Moscow focuses on military capabilities, and any state or organization that possesses substantial military potential can become a threat, marking a return to the Cold War view of the world.3

The primary security concern with NATO is the missile defense system launched in 2016. Since the early phase of its development, Russia was concerned that it could undermine its strategic deterrent. Even if the system is not directed against Russia and can’t intercept missiles launched from its territory because Russian ICBMs are too fast to be caught by the interceptors, Moscow is worried about what the system could become. Indeed, Valery Gerasimov, current Chief of the General Staff of the Armed Forces of Russia and first Deputy Defense Minister, declared in 2012 that “’the concept of the BMD system being implemented is global by nature’ […] and that ‘such a configuration is a threat to the Russian strategic nuclear deterrent assets across [the] whole country.’” The missile defense system, combined with NATO conventional and special superiority, could undermine the Russian deterrent if the system was directed against it in the future.4

The second source of concern has to do with the nature of NATO governments and colored revolutions in Georgia, Ukraine, and Kyrgyzstan. These revolutions were perceived as threatening Russia because in Georgia and Ukraine, they led to the election of presidents who favored their countries joining NATO. Moscow blamed NATO governments for backing the opposition and trying to take advantage of the 2007-2008 electoral cycle to bring similar changes to Russia. In the eyes of the Russian regime, these revolutions put the stability of the region at risk, menaced to reduce Russian influence, and enhanced the danger of NATO enlargement.5 This last point has always been a source of tension for Russia, so these revolutions did little to reassure Russia about NATO’s intentions and to reduce Russia’s hostility.

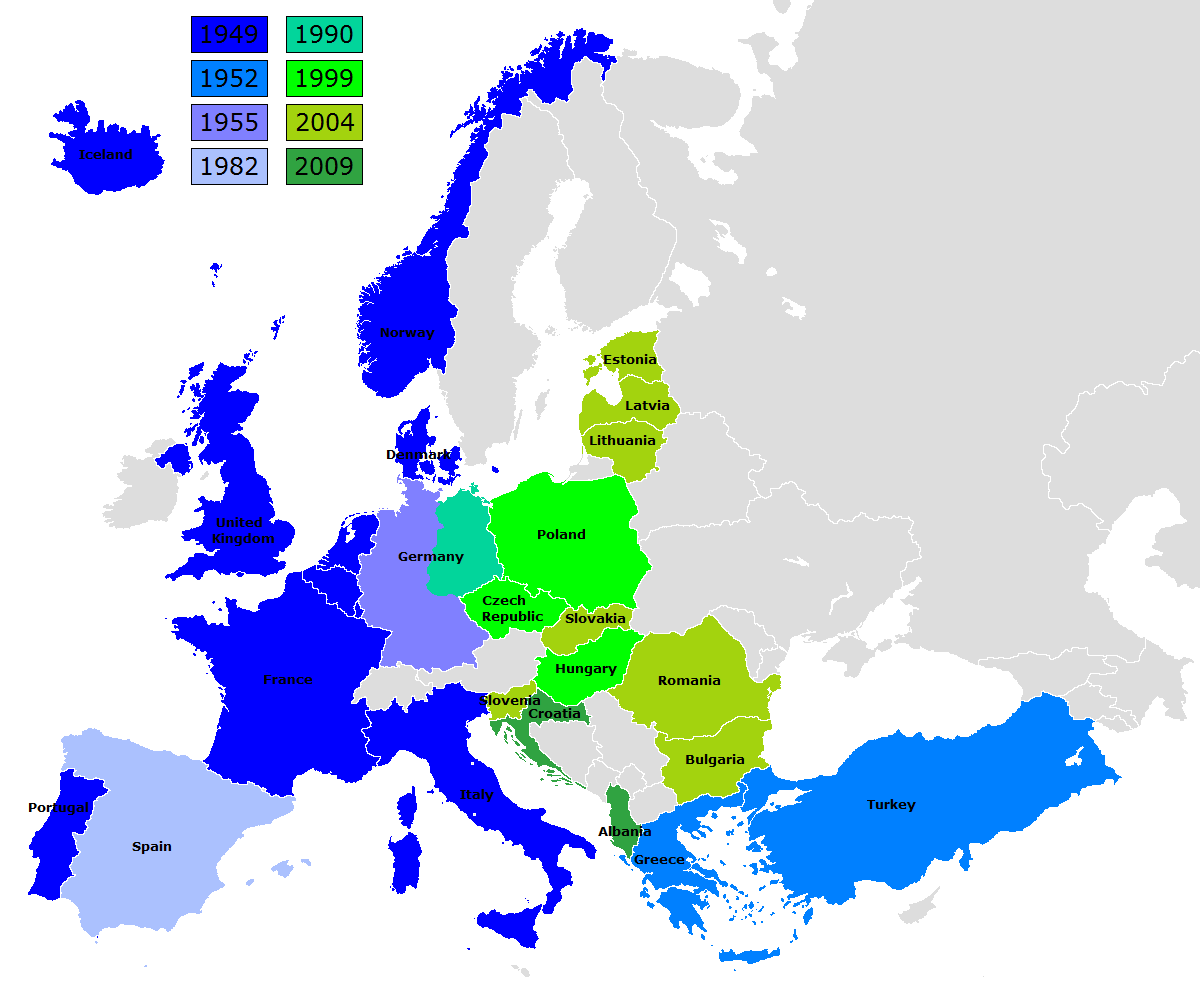

Indeed, NATO enlargement was seen as breaking the assurances given by U.S Secretary of State James Baker to Mikhail Gorbachev at the time of German reunification.6 Consequently, since its first phase, NATO enlargement was perceived negatively by Russians inasmuch as they tended to conclude that it demonstrated Western countries’ will to take advantage of Russia’s weaknesses after the collapse of the Soviet Union.7 Moreover, they feared a potential deployment of U.S. forces in the Baltic States that would threaten Russia’s borders.8

However, NATO seems to be an indirect threat to Russian security. Rather, it represents a threat to Russia’s status. Alliance enlargement is a security threat inasmuch as in the Russian perspective, what threatens the status quo also threatens their security. Indeed, since the beginning of its enlargement, it seems that the Russians were more concerned about the fact that the strengthening of NATO in the former Republics could prevent Russia from restoring its former world status.9 According to Russian elites, NATO enlargement “would lead to the diminution of the Federation’s influence in the world and worsen its geopolitical and geostrategic situation.”10 When the expansion began, Moscow feared that it was about to lose the last remnants of influence it had in Europe.11 Indeed, the Russians lost the Warsaw Pact, Ukraine, and Georgia that were the cornerstone of their regional hegemony and power status. The prospect of losing those countries to NATO affected Russia’s self-image and reinforced its feeling of isolation. Besides, with their perception of reality in terms of spheres of influence and geopolitics as a zero-sum game, the addition of former Soviet states to NATO is seen as an aggression and the intent of NATO to keep Russia to the status of an inferior actor.12

In addition, Russia’s anxiety about NATO expansion, despite the Alliance’s claims that it would stabilize the region and favor a more secure environment, certainly comes from the fact that the country felt excluded and isolated by Western powers.13 A sentiment that later reinforced Moscow’s perception that relations with NATO during the 1990s and early 2000s involved humiliating experiences from the two phases of NATO enlargement in 1999 and in 2004 to the colored revolutions and the missile defense system.14 Added to the intervention in Kosovo, considered as another humiliating move by NATO since it had been done without Russia’s blessing, Moscow feels that the Alliance tends to act on its own without consideration for the principles established by the 1997 NATO-Russia Founding Act.15

A first explanation for Russia’s hostility is the dynamic of security dilemma. Russia is hostile to NATO because it can become a threat to the Federation’s security and status. NATO enlargement, out-of-area orientation, and missile defense program are worrying Russia because they can reduce its influence in its neighborhood. However, these fears are a consequence of Russia’s political and strategic culture.

Opposed Values and Culture

Russia’s anxiety can also be explained by major differences in strategic cultures that shape threat perception and responses to security challenges. Indeed, Russia still views security in terms of geography and realpolitik. Thus, Moscow is worried about the influence of external actors in what they consider to be Russia’s security space and views international relations in zero-sum terms. In going back to a Cold War mindset, Russia seems to be worried about its bordering regions, regions it sought to dominate for centuries. This vision of international relations prevents it from engaging in full cooperation with other players and makes the country uneasy about the presence of other major powers in its traditional sphere of influence.

In this context, most Russian leaders believe that the most effective strategy for managing relations with other international players is through competition. In their view, NATO represents not only a major player in the region, but also a concurrent vision of international relations stressing the de-territorialized nature of security challenges and a coexistence of diverse strategic cultures that Moscow finds confusing.16 Indeed, Russia and NATO promote two different models of government and have two different visions for the security in Europe This ideological competition takes the form of two visions of European security, a NATO-centric model aiming to make the behavior of Eastern European countries more predictable and to ensure democratic governance, and a model where NATO is assigned to the OSCE, the key security organisation in Europe. When Moscow grew disappointed with the OSCE, the EU became the pillar of Russia’s model. However, the EU was difficult to deal with and Moscow decided to establish a three pillars model where Russia, the EU and NATO were the balancing powers.17

Additionally, Hannah Smith argues that the rivalry between Russia and NATO can be traced back to the 19th century when there was political rivalry between more liberal (France and the United-Kingdom) and more conservative (Germany, Russia, and the Austria-Hungary) countries. They did not share the same views in terms of human rights and acceptable forms of government, and clashed over imperial rivalries and economic interests. Russia’s hostility toward NATO can be explained by this great power rivalry as Moscow perceives the state identity supported by NATO as a danger to its power elite in the same way that the French Revolution or British liberalism threatened the power of the tsars. Furthermore, the norms of government and societies shared by NATO members do not fit with Russia’s perception of its traditional forms of identity.18

This imperial past can be observed today with Putin’s speeches about Novorossiya and the return to Crimea to its “native shores.” Moreover, since the Ukrainian crisis, Moscow is reaffirming the need for Russia to establish a democracy and a foreign policy that is consistent with Russia’s traditions, culture, and morale values that are contrasted with “the decadence of the West.”19 This animosity is intensified by the fact that Russia lost its empire with the fall of the Soviet Union and witnessed the survival, increasing popularity, and expansion of NATO. As the latter represents and supports a political and economic system that is alien to Russia’s political legacy, it is seen as a threat to a country that has lost its great power status.20

Fueled hostility With Dangerous Consequences

NATO never stated that its actions were directed against Russia, the threats perceived by Russia is primarily psychological and self-imposed. However, unlikely as a hostile NATO appears, Russia’s apprehensions and return to Cold War thinking have severe consequences since the election of President Vladimir Putin. Since then, Russia is following what Stephen Walt has called the “balance of threat theory.” According to it, “state behavior is determined by the threat perceived by other states or alliances” and it balances against other states that are perceived as a threat.21 Moscow’s invasion of Georgia in 2008 and involvement in Ukraine in 2014 are examples of this balancing. Indeed, as explained above, Moscow perceives all defense measures taken by NATO as vital threats. Russian intervention in Georgia in 2008, involvement in Eastern Ukraine, and the annexation of Crimea are ways to balance the perceived threat posed by NATO. Indeed, in the case of Ukraine, Russia’s objective is not to reconquer the country, but to make sure that the regime instituted and sustained in Ukraine will represent no harm to Russia’s interests and that the situation is sufficiently unstable to prevent its accession to NATO.22

The problem is that balancing threats exacerbates the dynamics of the security dilemma and makes the perceived threats real.23 Ukraine is a good example of this. Indeed, when Russia tried to balance the threat it thinks NATO represents, Russia increased the threat it poses to its neighbors, thus making NATO cease all cooperation and deploy troops to the Baltic States, a step Russia feared at the beginning of NATO expansion.24

Today, it seems that without a change of political system and culture, Russia is unlikely to see NATO as an entity with which it can cooperate, but that does not means that the Alliance should ‘play Russia’s game’ by ignoring Moscow’s view. This would only continue the escalation of tensions. Of course, NATO shouldn’t cease all its projects to reassure Russia, but the Alliance shouldn’t minimize Russia’s fear of isolation from and destabilization by Western powers. In order to do so, when they have to deal with Russia’s neighbors, NATO and Western powers should accept and state clearly that it will respect the sovereign decisions of non-members in how they politically order their societies and do not pledge to attempt to change the system of government of other states.25

Conclusion

Russia’s hostility toward NATO seems to be due to two sets of reasons. Since the fall of the Soviet Union, Russia sees NATO as a threat not only for its security because of NATO expansion and missile defense system, but also for its desire for great power status because NATO expansion reduced Russia’s influence in the region and promulgated political and strategic values in contention with its own. In regards to the security dilemma, Moscow feared that NATO would try to use colored revolutions to bring democratic change in the country, deploy U.S. troops on its borders, isolate Russia, and thus prevent it from supporting its own allies in the region. However, before Russia’s annexation of Crimea, NATO tried to reassure Russia about its missile defense program and expansion.26 It seems clear that NATO does not pose a direct threat to Russia, but that Moscow’s hostility is due to the different values the Alliance represent and the perceived insensitivity for the Federation’s fears. Indeed, since his first election as President, Putin reaffirmed the need for Russia to defend Russia’s traditional values and norms, which are, in his mind incompatible with those defended by NATO members. It seems that Russia’s hostility is more psychological and reflects a deep sense of political insecurity and vulnerability that fuels its efforts to balance NATO. Thus, it makes Russia’s perceived insecurity become real, and reinforces its own hostility and the dynamics of the security dilemma in Europe.27

Corentin Laguerre has a M.A. in War Studies from King’s College London.

References

1. Hanna Smith, “Russian Threat Perceptions: Shadows of the Imperial Past”, War on the Rocks (2015), online

2. Col. Robert E. Hamilton, “Georgia’s NATO Aspirations: Rhetoric and Reality”, FPRI (2016), online

3. Stephen Blank, “Threats to and from Russia: An Assessment”, The Journal of Slavic Military Studies 21:3 (2008), 499

4. Roberto Zadra, “NATO, Russia and Missile Defence”, Survival 56:4 (2014), 53-54

5. Peter J.S. Duncan, “Russia, the West and the 2007-2008 Electoral Cycle”, Europe-Asia Studies 65:1 (2013), 2-3, 9

6. Idem., 16

7. Sharyl Cross, “NATO-Russia Security Challenges in the Aftermath of Ukraine Conflict”, Southeast European and Black Sea Studies 15:2 (2015), 154

8. Leonid A. Karabeshkin & Dina R. Spechler, “EU and NATO Enlargement”, European Security 16:3 (2007), 314-315

9. Aurel Braun, “NATO and Russia: Post-Georgia Threat Perceptions”, Russie.Nei.Visions 40, Ifri (2009), online, 10-11

10. Leonid A. Karabeshkin & Dina R. Spechler, “EU and NATO Enlargement”, European Security 16:3 (2007), 314

11. Dmitry Polikanov Director, “NATO-Russia Relations: Present and Future”, Contemporary Security Policy 25:3 (2004), 480

12. Arthur R. Rachwald, “A ‘reset’ of NATO-Russia relations: real or imaginary?”, European Security 20:1 (2011), 118-119

13. Dmitry Polikanov Director, “NATO-Russia Relations: Present and Future”, Contemporary Security Policy 25:3 (2004), 480

14. Oksana Antonenko & Bastian Giegerich, “Rebooting NATO-Russia Relations”, Survival 51:2 (2009),

15. Dmitry Polikanov Director, “NATO-Russia Relations: Present and Future”, Contemporary Security Policy 25:3 (2004), 481

16. Oksana Antonenko & Bastian Giegerich, “Rebooting NATO-Russia Relations”, Survival 51:2 (2009), 15-16

17. Dmitry Polikanov Director, “NATO-Russia Relations: Present and Future”, Contemporary Security Policy 25:3 (2004), 482

18. Hanna Smith, “Russian Threat Perceptions: Shadows of the Imperial Past”, War on the Rocks (2015), online

19. Sharyl Cross, “NATO-Russia Security Challenges in the Aftermath of Ukraine Conflict”, Southeast European and Black Sea Studies 15:2 (2015), 158-159, 161

20. Arthur R. Rachwald, “A ‘reset’ of NATO-Russia relations: real or imaginary?”, European Security 20:1 (2011), 117, 120

21. Andreas M. Bock, Ingo Henneberg & Friedrich Plank, “If you compress the spring, it will snap hard: The Ukrainian crisis and the balance of threat theory”, International Journal 70:1 (2015), 102-103

22. Idem, 102-103

23. Idem, 103

24. Tuomas Forsberg & Graeme Herd, “Russia and NATO: From Windows of Opportunities to Closed Doors”, Journal of Contemporary European Studies 23:1 (2015), 52

25. Col. Robert E. Hamilton, “Georgia’s NATO Aspirations: Rhetoric and Reality”, FPRI (2016), online

26. Idem.

27. Arthur R. Rachwald, “A ‘reset’ of NATO-Russia relations: real or imaginary?”, European Security 20:1 (2011), 125 & Andreas M. Bock, Ingo Henneberg & Friedrich Plank, “If you compress the spring, it will snap hard: The Ukrainian crisis and the balance of threat theory”, International Journal 70:1

Featured Image: Luxembourg’s armed vehicles during Iron Sword 2016 in Lithuania. (NATO)