By Vince DePinto

Introduction

According to the 2016 Marine Corps Operating Concept (MOC), the greatest risk to the Marine Corps is that it becomes unbalanced in its development as a force that is at once naval, expeditionary, agile, and lethal.1 Four decades of institutional neglect of naval surface fire support (NSFS) has led to precisely that: the Corps is over-reliant on aviation and cruise missiles to provide fires in a non-permissive maritime domain. Without investment in NSFS solutions that balance capability and capacity, the Marine Corps will be constrained in its ability to maneuver at sea, leaving Marines ill-equipped to fight and win in the future operating environments the MOC predicts.

The MOC makes it clear, though, that identified problems should be accompanied with feasible solutions: Marines innovate and adapt to win. By developing innovative tactics and munitions for the existing high mobility artillery rocket system (HIMARS) and by adapting the San Antonio-class amphibious transport docks (LPD) to support a naval gun, the Marine Corps can fulfill the MOC’s call for an agile, lethal, and expeditionary force with an ability to secure the sea control essential for the prosecution of naval campaigns.

The Problem: The Neglect of Naval Surface Fire Support

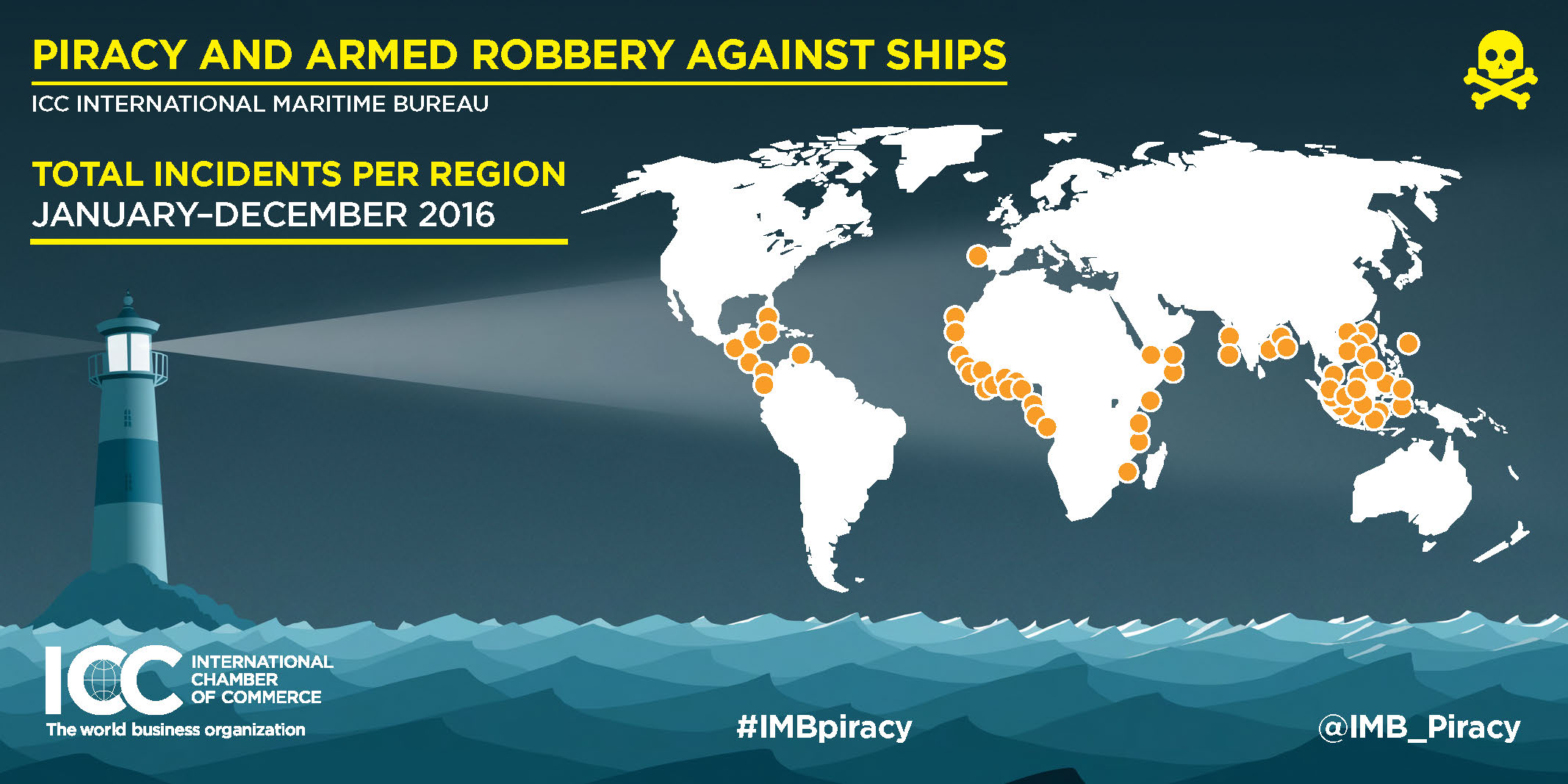

The MOC opens by stating that the Marine Corps is “not organized, trained, and equipped to meet the demands of a future operating environment characterized by complex terrain, technology proliferation…and an increasingly non-permissive maritime domain.”2 While some critics dismiss NSFS as an anachronism in the modern context, it is the increasing complexity of advanced anti-access area-denial (A2/AD) weapon systems and the subsequent proliferation of such affordable capabilities that necessitates its revival. Detractors argue that naval aviation and the Navy’s Tomahawk Land Attack Missile (TLAM) complement are sufficient to service targets in support of an amphibious force. In a permissive maritime environment, this argument is likely valid. However, rival powers have identified America’s critical capabilities and are preparing to remove them accordingly; a reality the MOC identifies as a future constant.3 Nowhere is this more evident than in the Western Pacific. Over the past two decades, the People’s Republic of China (PRC) has invested considerable resources into acquiring the capabilities necessary to deter, counter, and defeat adversarial power projection into regional conflicts.4 The People’s Liberation Army (PLA) fields a comprehensive battle network of sensors, platforms, and weapons that form a robust, multi-domain reconnaissance-strike complex capable of effectively engaging naval vessels over 800 miles from China’s shores.5

As these threats force the surface groups’ operational areas further from the adversary, the tyranny of distance restricts Marine aviation’s ability to influence the environment. Increased range forces the platforms to dedicate more weight to fuel over munitions and limits time on target. Extended distance also prohibits the use of some platforms outright. For example, rotary-wing attack aircraft are restricted to operating within 120 nautical miles of a fuel source, and fixed wing aircraft do not fare much better. While the F-35 is a revolutionary airframe with inherent stealth characteristics, the high value air assets (HVAA) on which it depends are not so resilient. In “Short Legs Can’t Win Arms Races,” Greg Knepper and Peter Singer identify airborne refueling tankers as the weakest link in America’s kill chain.6 They argue that the removal of a single tanker could lead to a flight package aborting its mission, or the destruction of the entire complement, if (when) fuel expires.7 The design of the PLA’s fifth generation stealth aircraft, the J-20, increasingly resembles that of a long-range interceptor. Analysts assess such a design is optimized to engage America’s critical HVAA with long-range air-to-air missiles, a tactic consistent with Chinese operational and strategic thought.8

A common counter-argument is that long-range cruise missiles, such as TLAMs, will be used to neutralize threats in order to enable follow-on aviation operations. Libya is cited as a textbook example for “rolling back” an integrated air defense system, with submarines removing the threats necessary to support follow-on aviation operations. Unfortunately, the Navy may lack the capacity to support this approach in the years to come, losing the tremendous 154 TLAM payload of each of the four modified Ohio-class submarines (SSGNs) when the boats are retired by 2028.9 The Virginia-class payload modules are intended to replace the SSGN’s strike capability, but with 40 TLAMs they are arguably insufficient against the demands posed by conflict with a near-peer power.10 In a hypothetical contest with the PRC, such shortfalls are compounded by the escalating threat posed by China’s increasingly stealthy and lethal undersea fleet: a force that is expected to deploy over 70 vessels by 2030.11 While the exceptionally quiet Virginia submarines provide America with a qualitative undersea advantage, the Navy expects to have roughly 41 in service by 2029.12 This reinforces the likelihood that the undersea force will be restricted in its ability to support Marines ashore, likely prioritizing anti-submarine and anti-surface warfare missions above strike.13

Tomahawk cruise missile launched from USS Florida (SSGN-728)

If one continues to use the ‘Roll Back’ concept, then surface combatants will be forced to mitigate the TLAM shortfall. This highlights a second critical vulnerability of the force: surface combatants cannot reload their VLS at sea. Broadly speaking, Ticonderoga-class guided missile cruisers (CG) are equipped with a VLS that can support 122 missiles and Arleigh Burke-class guided missile destroyers (DDG) are capable of storing 96.14 The VLS missile silos are outfitted in accordance with the threat environment. Operations in a non-permissive maritime environment will necessitate a readiness to counter a variety of threats and support a wide range of missions in addition to surface strike, such as ballistic missile defense, anti-surface warfare, anti-submarine warfare, and anti-air warfare. Much like the submarine force, it is not unreasonable to think that during a crisis with a near-peer power, strike will be the lowest priority. Therefore, the number of available TLAMs will be significantly below the maximum capacities outlined above. Indeed, the protection of the Navy’s capital ships remains a priority in current doctrine, further eroding the potential of a strike-centric cruiser or destroyer in a contested battlespace.15

Moreover, new operational concepts may exacerbate the NSFS shortfall. The Navy’s answer to the proliferation of A2/AD weapon systems is known as distributed lethality (DL). The core thrust of DL is that the Navy seeks to strain an adversary’s ability to assess and act by “spreading the playing field.”16 As Admirals Rowden, Gumataotao, and Fanta state, “Distributed lethality is the condition gained by increasing the offensive power of individual components of the surface force and then employing them in dispersed offensive formations.”17 There is potential that disaggregation of surface groups will increase the geographic distance between the vessels expected to provide NSFS and the operating areas of Marines ashore.

Even then, TLAMs are not necessarily the best or most economical solution to support maneuver units. The Department of the Navy states that a TLAM’s speed is roughly 550 mph.18 If a maneuver unit was conducting operations 30 nautical miles over the horizon, this would result in over three and a half minute time of flight, hardly ideal for troops in contact. TLAMs could be vulnerable to GPS spoofing or jamming, and could be engaged by adversaries’ point defense systems. The excessive cost would restrict the requesting unit’s ability to bracket a target or call for re-attacks in such events. If one uses $607,000 as a TLAM’s unit cost, the Navy expended over $121,400,000 of cruise missiles during the operation in Libya.19 This is hardly sustainable, which leaves the Mk-45 5-inch gun as the only current alternative NSFS capability.

The Mk-45, found on most cruisers and destroyers has a range of roughly 13 nautical miles though the Navy plans to field an extended-range projectile that could reach 30 nautical miles. If the Marine Corps views the promised munition with skepticism, it would be justified. The recent cancellation of the Long-Range Land Attack Projectile (LRLAP) manifests the sad state of NSFS affairs. The Iowa-class battleships were retired with the assurance that the Navy would acquire a vessel that would meet or exceed the battleships’ NSFS capability. The Navy intended to purchase 29 ships of what was then referred to as the DDX program, which eventually metastasized into the Zumwalt-class destroyer.20 After suffering consistent cost overruns and ultimately being truncated in favor of procuring more DDG-51s, the Zumwalt-class will yield three ships instead of the promised 29.21 The decreased ship count has led to the cancellation of the LRLAP round, the intended munition for the Zumwalt-class’s Advanced Gun System (AGS). Strangely, the AGS and the LRLAP were two of the only technologies that were not subject to development delays or cost over-runs that plagued the DDX program.22 The LRLAP was cancelled as the unit costs would not depreciate to a tolerable threshold in light of the decreased quantity of deployed guns.23

If the NSFS deficit of the fleet is not rectified, the Marine Corps will be limited in its ability to maneuver in a contested maritime environment. To paraphrase the legendary Chesty Puller, “You can’t hurt ’em if you can’t hit ’em.”

Leveraging Legacy Systems: Maritime HIMARS

NSFS publications all too often end with gold plated solutions: the revival of the Iowa-class battleships, for example, or the fielding of a NSFS specific ship class, such as the Arsenal Ship.24 Yet, the MOC charges Marines to develop solutions that are technically feasible and institutionally affordable.25 While the thought of an un-mothballed USS New Jersey delivering a full nine-gun broadside is certainly patriotic, the operational requirements demand NSFS solutions that possess more range than what the venerated 16 inch guns can deliver.26 In “Bring Your Own Fires,” John Spang argues that the high mobility artillery rocket system/multiple launch rocket system (HIMARS/MLRS) is an ideal solution to the NSFS dilemma.27 The technology and the support procedures already exist. The trucks are purchased, the Marines trained, and the munitions proven in combat. The Marines should seize the current enthusiasm for military expansion by adding HIMARS battalions to the existing two.

The HIMARS launcher carries two families of guided missiles: the guided multiple-launch rocket system (GMLRS) and the Army Tactical Missile System (ATACMS). The GMLRS can strike targets at 48 nautical miles, while the ATACMs missile has the capability of launching a 500lb high explosive warhead 162 nautical miles.28 While the HIMARS is a road-mobile system, it has been fired at sea. In 1995, the Army successfully fired tactical ballistic missiles off the fantail of the USS Mount Vernon (LSD-39).29 This highlights not only technical feasibility, but a dramatic increase in warfighting potential. An embarked HIMARS converts any ship capable of handling the weight and the missile back blast into a NSFS platform. This dovetails almost perfectly into Admiral Fanta’s distributed lethality motto, “If it floats, it fights.”30 HIMARS systems and their rocket pods could be latched down to any vessel with a flight deck, weaponizing civilian, merchant marine vessels, or even auxiliaries such as the Expeditionary Transfer Dock or the Expeditionary Sea Base. When required to echelon ashore, the CH-53K could externally lift the launchers to support the ground scheme of maneuver, providing an additional return on investment in the form of operational tempo and initiative. It is even possible that HIMARS could be adapted for use as a NSFS module on a Littoral Combat Ship, provided the heat of the missile launch does not compromise the integrity of the aluminum hull.

The shipboard use of HIMARS aligns with PACOM commander Admiral Harris’ call for cross-domain fires.31 At the 2016 Land Power in the Pacific Symposium, Admiral Harris called on the Army to be “back in the business of killing ships,” employing modified artillery shells and HIMARS missiles to sink enemy men of war. The Department of Defense is moving forward with this concept by developing an ATACMs variant capable of engaging moving targets on both land and sea. This mission should be seized by the Marines, both due to the statutory responsibility of seizing and defending advanced naval bases, and because it fulfills the MOC’s aims of a Corps equipped to support sea control.32

The integration of the existing HIMARS system would inevitably result in tactical and operational trade-offs: the vehicles would likely be placed on flight decks, limiting aviation operations. Nevertheless, a modular, easily-distributed strike capability would force the adversary to contend with yet another ‘stick.’ HIMARS equipped with long range, surface-to-surface, and anti-ship missiles could sever an enemy’s interior lines of communication, reinforce and support surface combatants, and maintain localized pockets of sea control.33 Comparably low-cost, low signature, and highly mobile anti-ship missiles systems could leverage the complicated littoral geography of the Western Pacific, creating a ‘Murderer’s Row’ with allied and like-minded nations between enemy harbors and assessed operating areas.34,35 This would in turn exhaust the People Liberation Army’s command and control architecture, forcing the PLA to not only search a huge number of locations, but have the assets in place to target them, significantly diluting the effectiveness of the much lauded PLA missile and air forces.36

Giving the Gators Teeth

In light of the distributed lethality operational concept, the Navy is looking toward up-gunning the ‘gators.’37 Original designs of the San Antonio-class LPD called for two 8-cell Mk-41 VLS in the bow of the ship, but the cells were cut during development.38 Marine Commandant General Neller has expressed public enthusiasm for reversing this decision, stating that the addition of the VLS to the LPD would “change the game.”39 The addition of missiles would provide long-range fires to Amphibious Ready Groups or Marine Expeditionary Units, and support disaggregated, independent operations by the LPD. While the addition of 16 TLAMs would increase the LPDs’ lethal capability, it does not appreciably improve NSFS capacity, especially if the LPD is operating independently. The lack of a reload capability restricts tactical flexibility for fire support: the threshold to expend a TLAM would likely limit small, distributed units from exploiting gaps and seams as they develop. It also limits operational flexibility as the small magazine would prevent longer operations and limit time on station.

Instead of installing a VLS into the LPD, the services should investigate the possibility of installing a naval gun. Quantity has a quality all of its own: guns provide a capacity that a 16 cell VLS does not. From an economic perspective, the use of a naval gun allows the Navy to invert the acquisition model from one centered on high-cost, low capacity missile purchases to a low cost, high-capacity gun system that will would enjoy better economy of scale.40 While the initial costs in ship modification may be more expensive when compared to the VLS, the price dynamics of a gun system are more favorable than TLAMs over the long term, especially given the tactical dividend of the gun’s ability to be reloaded indefinitely at sea.

A potential course of action could be the Advanced Gun System Lite (AGS-L), a modified AGS that was designed to fit into the same space as the Mk-45 5-inch gun found on most surface combatants.41 The AGS-L is capable of firing the LRLAP to its 71 nautical mile range, at six rounds per minute, housing up to 240 LRLAP rounds in the magazine. 42,43 More importantly, the modification of the LPDs to support deck guns would allow the ships to capitalize on the future Hyper Velocity Projectiles (HVP) that are currently in development for strike and air defense.44 Capable of being fired from a traditional gun, HVPs launched from the AGS are capable of intercepting cruise missiles at ranges over 10 nautical miles, but are exponentially more affordable than the Evolved Sea Sparrow Missiles currently stocked in the VLS for defense.45,46 When Houthi rebels attacked the USS Mason with Chinese-produced C-802 anti-ship cruise missiles in October, James Holmes estimated that it cost the Navy upwards of $8 million dollars to defend the vessel against enemy projectiles valued at $500,000 piece; a cost ratio of over 8-1.47 The installation of a naval gun not only allows the LPD an increased capacity to support troops ashore, but also position the fleet to take advantage of fiscally sustainable medium-range air and missile defense capabilities in development.48

Counter-arguments to the retrofitting of the AGS-L into standing surface combatants exist. Studies would have to identify the effect of the gun on other naval systems, specifically the heat, vibration, and gases. Of most relevance is the ship’s superstructure: will the bridge’s fragility prohibit a gun entirely? While BAE promotional materials highlight the similarities of the physical dimensions between the Mk-45 and the AGS-L, careful attention would need to be paid to the extent at which the ship would have to be modified to support shell hoists, cooling, and magazine spaces. The back end logistics and life cycle maintenance would be an additional cost to consider.

While these challenges are indeed daunting, the ability for an LPD to provide NSFS to the Marines already embarked would relieve other surface combatants and their magazines to prosecute other warfighting functions. An LPD is already better suited to provide NSFS because her engines and fuel supply allow for longer on-station times compared to cruisers or destroyers. On a personal level, the LPD crew providing fires to her previously embarked Marines could yield a familiar and habitual relationship between supporting and supported units, leading to increased combat effectiveness (and plenty of opportunities to practice processes while underway).49 Combined with her reduced radar cross-section, aviation space, and command and control capability, the LPD would be in a unique position to operate independently, supporting distributed operations across the maritime domain.

Conclusion

If the MOC desires a force capable of securing sea control in order to support power projection in future operating environments, it must invest in NSFS solutions today. Imagine multiple, independently operating LPDs providing NSFS to distributed Advanced Expeditionary Bases armed to the teeth with ship-killing, low signature HIMARs detachments. The absence of capable NSFS threatens to yield a future Corps that is not only unbalanced, but possibly irrelevant. The most dangerous weapon in the world is a Marine and their rifle, a modern, usable, and cost-effective NSFS capability ensures they can get into the fight.

Captain Vincent J. DePinto, USMC is an Intelligence Officer who served two tours in the Pacific. He holds a graduate degree from the National Intelligence University and is a student in the Naval War College’s Fleet Seminar Program. He can be reached at vindepinto@gmail.com.

References

1. Department of the Navy. The Marine Corps Operating Concept: How an Expeditionary Force Operates in the 21st Century. Washington, DC. Headquarters, United States Marine Corps, 2016.

2. Ibid

3. Shugart, Thomas. Has Chine Been Practicing Preemptive Missile Strikes Against U.S. Bases?. https://warontherocks.com/2017/02/has-china-been-practicing-preemptive-missile-strikes-against-u-s-bases/?utm_source=Sailthru&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=New+Campaign&utm_term=%2ASituation+Report (Accessed February 7, 2017)

4. Secretary of Defense. Annual Report to Congress: Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China 2016. Arlington, Virginia : Department of Defense , 2016.

5. Sloman, Jesse, and Bryan Clark. Advancing Beyond the Beach: Amphibious Operations in an Era of Precision Weapons. Washington, D.C.: Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments, 2016.

6. Knepper, Greg and Singer, Peter. Short Legs Can’t Win Arms Races: Range Issues And New Threats To Aerial Refueling Put U.S. Strategy At Risk. May 20, 2016. https://warontherocks.com/2015/05/short-legs-cant-win-arms-races-range-issues-new-threats-aerial-refueling/ (accessed November 29, 2016).

7. Ibid

8. Lockie, Alex. The Real Purpose behind China’s Mysterious J-20 Combat Jet. January 24, 2017. http://www.businessinsider.com/the-real-purpose-behind-chinas-mysterious-j-20-combat-jet-2017-1 (Accessed January 27, 2017)

9. Ron’ Rourke, Navy Virginia (SSN-774) Class Attack Submarine Procurement: Background and Issues for Congress, Congressional Research Service, October 25, 2016.

10. Ibid

11. Majumdar, Dave. Undersea Crisis: China Will Have Nearly Twice as Many Subs as the U.S. February 26, 2016. (Accessed January 27, 2017)http://nationalinterest.org/blog/the-buzz/undersea-crisis-china-will-have-nearly-twice-many-subs-the-15335

12. Ibid

13. Heginbotham, Eric. The US- China Military Scorecard: Forces, Geography, and the Evolving Balance of Power 1996-2017. http://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/research_reports/RR300/RR392/RAND_RR392.pdf (Accessed January 27, 2017)

14. Department of the Navy. USN Fact File. http://www.navy.mil/navydata/fact_display.asp?cid=4200&tid=900&ct=4 (January 14, 2016) and http://www.navy.mil/navydata/fact_display.asp?cid=4200&tid=800&ct=4 (January 9, 2017)

15. Rowden, Thomas, Peter Gumataotao, and Peter Fanta. “Distributed Lethality.” Proceedings Magazine, January 2015.

16. Ibid

17. Ibid.

18. Department of the Navy. USN Fact File. Department of the Navy. USN Fact File. http://www.navy.mil/navydata/fact_display.asp?cid=2200&tid=1300&ct=2 (August 14, 2014)

19. Reed, John. 2,000 Tomahawks Fired in Anger. August 4, 2011. http://defensetech.org/2011/08/04/2000-tomahawks-fired-in-anger/ Defense Tech. aspx (accessed November 10, 2016).

20. Joseph E. Santos and Andrew Stigler. “Littoral Combat Ship – A TKO for the Streetfighter,” A Case Study in Naval Force Planning, (Newport, R.I.: Naval War College, updated 2015).

21. Ibid

22. LaGrone, Sam. Navy Planning on Not Buying More LRLAP Rounds for Zumwalt Class. November 07, 2016 . https://news.usni.org/2016/11/07/navy-planning-not-buying-lrlap-rounds (accessed November 14, 2016).

23. Ibid

24. Duplessis, Brian. “Fixing Fires Afloat.” Marine Corps Gazette, 2015: 33-38.

25. Department of the Navy. The Marine Corps Operating Concept: How an Expeditionary Force Operates in the 21st Century. Washington, DC. Headquarters, United States Marine Corps, 2016.

26. Spang, John. “Bring Your Own Fires.” Marine Corps Gazette, February 2011: 70-71.

27. Ibid

28. Ibid

29. Erwin, Sandra. Marines Clamor for Long Range Artillery at Sea. January 2002. http://www.nationaldefensemagazine.org/archive/2002/January/Pages/Marines_Clamor6864.aspx (accessed November 10, 2016).

30. Rowden, Thomas, Peter Gumataotao, and Peter Fanta. “Distributed Lethality.” Proceedings Magazine, January 2015.

31. Osborn, Kris. Emerging DOD ‘Cross Domain Fires’ Strategy: Army Will Attack Enemy Ships. November 25, 2016. http://www.scout.com/military/warrior/story/1687351-emerging-dod-strategy-cross-domain-fires (accessed November 29, 2016).

32. Department of the Navy. The Marine Corps Operating Concept: How an Expeditionary Force Operates in the 21st Century. Washington, DC. Headquarters, United States Marine Corps, 2016.

33. Jensen, Benjamin Back to the Future: Distributed Maritime Operations. April 9, 2015. http://warontherocks.com/2015/04/distributed-maritime-operations-an-emerging-paradigm/ (accessed November 10, 2016).

34. Ibid

35. Holmes, James. Defend the First Island Chain. http://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/2014-04/defend-first-island-chain Proceedings Magazine, April 2014.

36. Terrence Kelly, Anthony Atler, Todd Nichols, and Lloyd Thrall. Employing Land-Based Anti-Ship Missiles in the Western Pacific. 2013. http://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/technical_reports/TR1300/TR1321/RAND_TR1321.pdf

37. LaGrone, Sam. Navy, Marine Corps Considering Adding Vertical Launch System to San Antonio Amphibs. October 13, 2016. https://news.usni.org/2016/10/13/vertical-launch-system-san-antonio-amphibs (accessed November 14, 2016).

38. Ibid.

39. Harper, Jon Marine Corps Eyeing Additional Amphibious Ships. January 12, 2017 http://www.nationaldefensemagazine.org/blog/Lists/Posts/Post.aspx?ID=2394 (accessed January 27, 2017).

40. Cooper, Maxwell. “The Railgun Advantage.” Proceedings, 2011.

41. Weyer, Brent, and Al Panek. “The 155mm Advanced Gun System-Lite (AGS-L) for DDG-51 Flight III: A Summary of the BAE Systems IRAD Effort.” BAE Systems Land & Armaments. BAE Systems, May 15, 2012.

42. Ibid

43. Kulshrestha, Dr S. Guns Remain in Navy’s Future Plans. 2014. http://www.spsnavalforces.com/story.asp?mid=33&id=3 (accessed November 14, 2016).

44. Mark Gunzinger, and Bryan Clark. Winning The Salvo Competition: Rebalancing America’s Air And Missile Defenses. Washington, D.C.: Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments, 2016.

46. Ibid

46. Department of the Navy. USN Fact File. Department of the Navy. USN Fact File. http://www.navy.mil/navydata/fact_display.asp?cid=2200&tid=950&ct=2 (January 25, 2017)

47. Holmes, James Is the U.S. Navy a Sitting Duck? http://foreignpolicy.com/2016/10/25/is-the-u-s-navy-a-sitting-duck-yemen-houthis-china/ (January 25, 2017)

48. Mark Gunzinger, and Bryan Clark. Winning The Salvo Competition: Rebalancing America’s Air And Missile Defenses. Washington, D.C.: Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments, 2016.

49. Duplessis, Brian. “Fixing Fires Afloat.” Marine Corps Gazette, 2015: 33-38.

Featured Image: A Marine with 3rd Battalion, 3rd Marine Regiment, runs forward while an Amphibious Assault Vehicle drives onto the sand behind him at Pyramid Rock Beach as part of the final assault during the Rim of the Pacific (RIMPAC) Exercise 2014. (U.S. Marine Corps photo by Sgt. Sarah Dietz/Released)