By Tuan N. Pham

Last March, CIMSEC published an article titled “A Sign of the Times: China’s Recent Actions and the Undermining of Global Rules, Part 1” highlighting three troubling developments that oblige the United States to further encourage and challenge China to become a more responsible global stakeholder that contributes positively to the international system. The article noted Beijing is trying to convince others to accept the self-aggrandizing and self-serving term of “near-arctic state”; to fulfill its nationalistic promise to the Chinese people and reclaim the disputed and contested South China Sea (SCS) from ancient times; and to expand its “sharp power” activities across the globe.

A month later, CIMSEC published a follow-on article underscoring that these undertakings continue to mature and advance apace. The article featured China possibly considering legislation to seemingly protect the fragile environment in Antarctica, but really to safeguard its growing interests in the southernmost continent; taking more active measures to reassert and preserve respectively its perceived sovereignty and territorial integrity in the SCS; and restructuring its public diplomacy (and influence operations) apparatuses to better convey Beijing’s strategic message and to better shape public opinion abroad. At the end of the article, the author commented that although the United States made progress last year calling out wayward and untoward Chinese behavior by pushing back on Chinese unilateralism and assertiveness, strengthening regional alliances and partnerships, increasing regional presence, reasserting regional influence, and most importantly, incrementally reversing years of ill-advised accommodation; there is still more America can do.

The following article lays out previously recommended ways and means that Washington can impose strategic costs to Beijing and regain and maintain the strategic initiative. Providentially, the Trump Administration has implemented many of them, but the real challenge remains in sustaining the efforts and making the costs enduring. Otherwise, Beijing will just wait out the current administration in the hopes that the next one will advance more favorable foreign policies. Alternatively, they could also step up their “sharp power” activities to influence extant U.S. foreign policies and/or undermine the current U.S. administration’s political agenda and diminish its re-election prospect in 2020.

What America Can Do in the Indo-Pacific

The new National Security Strategy and National Defense Strategy call for embracing strategic great powers competition with rising China. They both make the case that when two powers, one dominant (United States) and one rising (China), with competing regional and global strategies extend into one’s another security and economic spheres, the geopolitical landscape is ripe for friction. However, this competition is not to be feared but to be expected and embraced. America must challenge China’s rise if it continues to not be peaceful and undermines the global rules that provide global peace and prosperity for all.

China will likely remain the economic partner of choice for the Indo-Pacific, while the United States will likely remain the security partner of choice. As this China-U.S. competition grows and intensifies, balancing these complex and dynamic relationships will become increasingly challenging as regional countries feel greater pressures to choose sides. The U.S. should continue to pursue stronger regional security ties and strive to be a more dependable and enduring partner in terms of policy constancy, resolve, and commitment. Strengthening old alliances and partnerships, and forging new ones with Hanoi, New Delhi, and others will be beneficial.

The “most effective counterbalance” to China’s campaign of tailored coercion against its weaker neighbors will still be U.S. persistent presence and attention (and focus) in the form of integrated and calibrated soft and hard deterrent powers – multilateral diplomacy, information dominance, military presence, and economic integration.

The “most promising and enduring check” to China’s expansive regional and global ambitions will still be economic integration. The U.S. should move forward on more bilateral trade agreements; support the emerging Trans-Pacific Partnership-11 (TPP-11) initiative; and/or reconsider bringing back the TPP itself to bind the United States to the other regional economies, guarantee an international trading system with higher standards, and complement the other instruments of national power. Otherwise, Washington may inadvertently drive the Indo-Pacific nations toward other economic alternatives like the China-led Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership, Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, and Belt and Road Initiative.

China is a signatory of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) but often violates its provisions, whereas the United States has not ratified UNCLOS but has been its foremost champion on behalf of freedom of navigation, global commerce, and international rule of law. The U.S. should consider ratifying UNCLOS if challenges are going to have more gravitas and be taken more seriously by the international community, otherwise, the status quo simply strengthens Beijing’s ability to call into question Washington’s sincerity to international norms.

The U.S. must keep reframing and countering when appropriate the narratives that China pushes with accusations of American containment and hypocrisy while promoting a perception of China’s global benevolence and benign rise. Washington’s message is more often than not reactive and defensive, not synchronized, or sometimes nothing at all. The U.S. can seize the messaging initiative like during the 2017 Shangri La Dialogue with the keynote speech by Australian Prime Minister Turnbull, remarks by American Secretary of Defense Mattis during the first plenary session (United States and Asia-Pacific Security), and comments by former Japanese Minister of Defense Inada during the second plenary session (Upholding the Rules-based Regional Order). The U.S. can continue to acknowledge that both countries have competing visions, highlight the flawed thinking of Beijing’s approach, champion its own approach as the better choice, and call out wayward and untoward Chinese behavior when warranted. This can include China’s expansive polar ambitions, intrusive sharp power activities, and destabilizing SCS militarization, but the U.S. should also give credit or commend when appropriate, such as China’s economic sanctions against North Korea. The U.S. cannot euphemize in its messaging, and whenever possible, should synchronize communication throughout the whole-of-government and international partners while reiterating at every opportunity. There can be no U.S. policy seams or diplomatic space for China to exploit.

The U.S. must take each opportunity to counter China’s public diplomacy point-for-point, and keep repeating stated U.S. diplomatic positions to unambiguously convey U.S. national interests and values such as:

- The United States supports the principle that disputes between countries, including disputes in the ECS and SCS, should be resolved peacefully, without coercion, intimidation, threats, or the use of force, and in a manner consistent with international law.

- The United States supports the principle of freedom of navigation, meaning the rights, freedoms, and uses of the sea and airspace guaranteed to all nations in international law. United States opposes claims that impinge on the rights, freedoms, and lawful uses of the sea that belong to all nations. United States takes no position on competing claims to sovereignty over disputed land features in the East China Sea (ECS) and SCS.

- Claims of territorial waters and economic exclusive zones (EEZ) should be consistent with customary international law of the sea and must therefore, among other things, derive from land features. Claims that are not derived from land features are fundamentally flawed.

- Parties should avoid taking provocative or unilateral actions that disrupt the status quo or jeopardize peace and security. United States does not believe that large-scale land reclamation with the intent to militarize outposts on disputed land features is consistent with the region’s desire for peace and stability.

- United States, like most other countries, believes that coastal states under UNCLOS have the right to regulate economic activities in their EEZ, but do not have the right to regulate foreign military activities in their EEZ.

- Military surveillance flights in international airspace above another country’s EEZ are lawful under international law, and the United States plans to continue conducting these flights as it has in the past. Other countries are free to do the same.

What America Can Do in the SCS

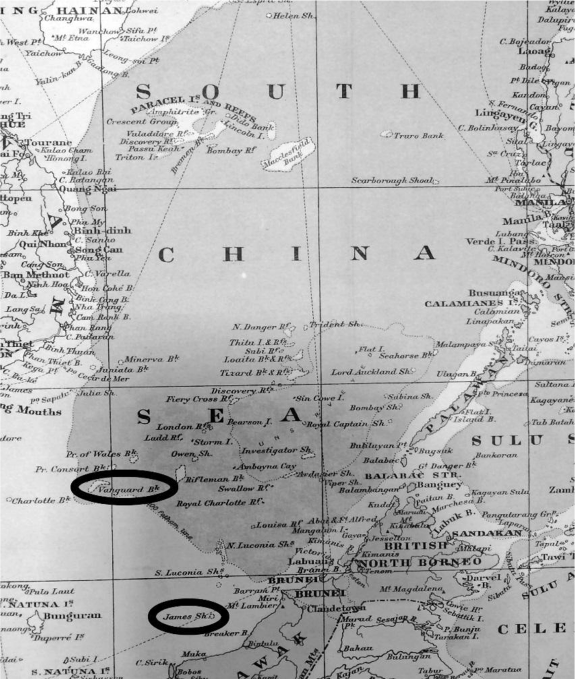

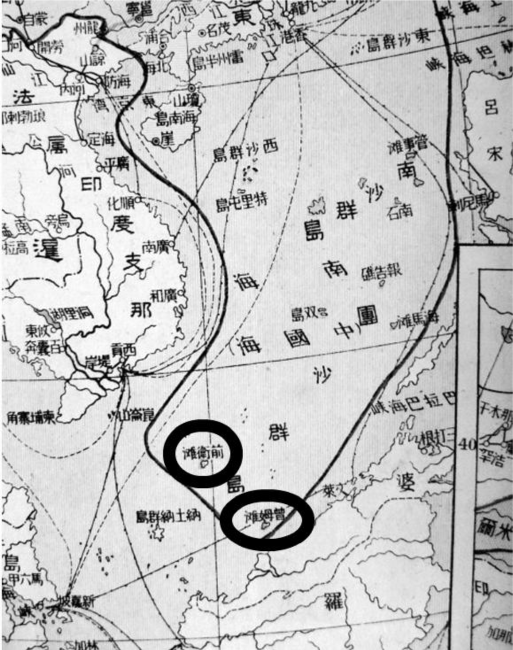

Since the start of 2018, China appears embarked on a calculated campaign to determinedly reassert and preserve its perceived sovereignty and territorial integrity in the SCS through words and deeds. Beijing believes that sharp and emphatic “grey zone” operations and activities will once again compel Washington to back down in the SCS. Washington did little when Beijing illegally seized Scarborough Shoal in 2012; brazenly reclaimed over 3200 acres of land over the next five years despite a 2002 agreement with the ASEAN not to change any geographic features in the SCS; barefacedly broke the 2015 agreement between Xi Jinping and Barack Obama to not militarize these Chinese-occupied geographic features; and blatantly disregarded the landmark 2016 Arbitral Tribunal ruling.

The U.S. can continue to reframe the SCS as a strategic problem (and not a regional issue) that directly involves the United States and obliges China to act accordingly. Explicitly conveying to Beijing that the SCS is a U.S. national interest and making the SCS a “bilateral” U.S.-China issue may induce Beijing to rethink and recalibrate its revisionist strategy. The U.S. can turn the tables and make Beijing decides which is more important to its national interests – the SCS or its strategic relationship with Washington (trade, military-military, etc.). Stay firm and consistent to stated SCS positions :

- No additional island-building and no further militarization

- No use of force or coercion by any of the claimants to resolve sovereignty disputes or change the status-quo of disputed SCS features

- Substantive and legally binding Code of Conduct that would promote a rules-based framework for managing and regulating the behavior of relevant countries in the SCS and permissibility of military activities in the EEZ in accordance with UNCLOS.

Otherwise, deferring to Beijing on aforesaid issues will only reinforce the perception in Beijing that Washington can be influenced and maneuvered with little effort.

Beijing undermined the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea by drawing red lines around the reclaimed and disputed geographic features. Washington and the international community must therefore buttress the Tribunal’s authority and legitimacy through words and deeds. There is value in continuing to challenge Beijing’s excessive and contested maritime claims in the SCS through a deliberate, calibrated, and enhanced campaign of presence operations – transits, exercises, and freedom of navigation operations (FONOP). Otherwise, failing to conduct these routine operations in the aftermath of the landmark 2016 ruling, particularly FONOPs, sends the wrong strategic signal and further emboldens Beijing to continue its brazen and destabilizing militarization of the SCS. Combined, multi-national exercises can underscore the universal maritime right of all nations to fly, sail, and operate wherever international law permits.

China pursues a very broad, long-term maritime strategy and will view any perceived U.S. force posture reduction as a reward (tacit acknowledgement and consent) for its unilateral rejection of the Tribunal ruling, a win for its strategy and preferred security framework, and another opportunity to reset the regional norms in its favor. Reduction may also increase Beijing’s confidence in its ability to shape and influence Washington’s decisions and encourage China to press the United States for additional concessions, in return for vague and passing promises of “restraint.”

Although Manila and Washington did not capitalize on the hard-fought legal victory over China’s excessive and contested maritime claims in the SCS, it is still not too late to do so. The U.S. can encourage and support Hanoi, Kuala Lumpur, and other Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) countries to put additional pressures such as legal challenges, public diplomacy, and collective maritime activities on Beijing to curb its assertiveness and unilateralism, stop its land reclamation and militarization activities, and come in good faith to the multilateral (not bilateral) negotiating table for a peaceful and enduring resolution of the competing and contested maritime claims.

Now is Not the Time to Back Down in the SCS

All told, years of American acquiescence and accommodation may have “unintentionally and transitorily” eroded international rule of law and global norms while diminishing the regional trust and confidence in U.S. preeminence. Furthermore, this accommodation may have weakened some of the U.S. regional alliances and partnerships, undermined Washington’s traditional role as the guarantor of the global economy and provider of regional security. These accommodations have accelerated the pace of China’s deliberate march toward regional preeminence and ultimately global preeminence.

So, as to not further give ground to Beijing in the strategic waterway, Washington cannot back down now in the SCS. To do so would further embolden Beijing to expand and accelerate its deliberate campaign to control the disputed and contested strategic waterway through which trillions of dollars of global trade flows each year and reinforce Beijing’s growing belief in itself as an unstoppable rising power and Washington as an inevitable declining power that can be intimidated out of the SCS and perhaps eventually the greater Indo-Pacific in accordance with its grand strategic design for national rejuvenation (the Chinese Dream). For Beijing, controlling the SCS is a step toward regional preeminence and eventually global preeminence.

Conclusion

Beijing’s strategic actions and activities are unwisely and dangerously undermining the current global order that it itself has benefited from. Hence, Washington has a moral and global obligation of leadership to further encourage and challenge China to become a more responsible global stakeholder that contributes positively to the international system. Otherwise, Beijing will continue to view U.S. acquiescence and accommodation as tacit acknowledgement and consent to execute its strategic ambitions and strategies unhindered and unchallenged. The U.S. window of opportunity to regain and maintain the strategic high ground and initiative will not remain open forever.

Tuan Pham serves on the executive committee of the Yokosuka Council on Asia-Pacific Studies and is widely published in national security affairs and international relations. The views expressed therein are his own and do not reflect the official policy or position of the U.S. Government.

Featured Image: Chinese dragon statute (Wikimedia Commons)