By Jimmy Drennan

Secretary of Defense James Mattis was on a plane last year, wrestling with how he would explain President Trump’s “America First” policy to our allies, when an idea came to him. He would draw a parallel to flight attendants requesting passengers put their own oxygen mask on first in the event of an emergency, before assisting family members. Say what you will about our national leadership, this is a wonderful metaphor. America can only contribute to the common interests of our Allies when we first secure our own national interests, across the entire political spectrum. Taking care of our own interests first allows America to be what our allies need – a strong, legitimate partner in promoting freedom and democracy.

Sliding all the way down the U.S. military chain of command, the youngest Seaman Recruit swabbing the deck on a Navy warship receives a very different message. He or she is taught a traditional saying that sailors use to succinctly describe their priorities: “ship, shipmate, self.” Like most nautical jargon, the aphorism has a certain graceful ring to it that captures the Navy’s mission-first mentality in very few words. It evokes dramatic notions of sailors agonizingly shutting a hatch on shipmates to save the ship from flooding, or sacrificing their own safety to save a shipmate from an engine room fire. Unfortunately, like most dramatic notions, these are largely fictional. In the real world, the U.S. Navy does not jump from one dramatic moment to the next. It operates a global force of six fleets, 284 ships, over 3700 aircraft, and 324,000 sailors, and it does so 24/7/365. Instead of maximizing mission effectiveness, using “ship, shipmate, self” as a set of priorities creates unrealistic expectations and tension in the minds of U.S. Navy sailors.

In truth, neither “America first” nor “ship, shipmate, self” are perfect models for sailors.

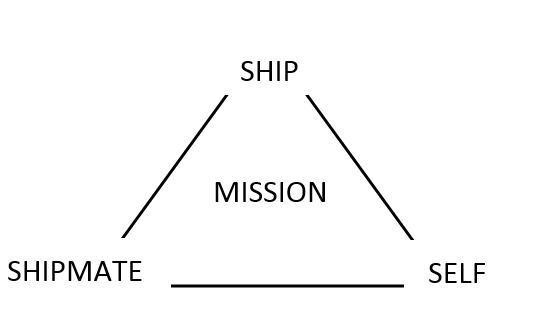

There are times when sailors truly should sacrifice their own interests and the interests of their shipmates for the sake of the ship, but more often than not, the energy they pour into the ship is in line with their own interests, not contrary to them. There are also many times when sailors need to prioritize their shipmates over the ship – just consider the massive amount of operational resources and time dedicated to recovering a single man overboard. Furthermore, and perhaps controversially, sailors often encounter situations in which they should prioritize themselves over their shipmates and their ship, although these situations often go unnoticed due to Navy culture epitomized by “ship, shipmate, self.” Over the past ten years, an average of 44 active duty sailors died by suicide each year. Imagine how many sailors could be saved by focusing on “preventive self-care” vice reactive clinical treatment. Many will probably view this “selfish” approach as subversive and contrary to what the Navy stands for, but radical ideas are often viewed this way at first. In fact, it is a dynamic approach to leadership that encourages emotional intelligence, in leaders and followers alike, to optimize mission effectiveness. To truly achieve sailor wellness and promote an effective mission-first culture, the Navy should use “ship, shipmate, self” not as a set of priorities, but rather as a triad with each element being critical to the mission.

Ship

Understandably, the ship is traditionally the focal point of naval operations. For centuries, ships were the only means that the world’s navies had at their disposal to project power on their enemies.

Today, even with the advent of naval aircraft, missiles, and other deployable systems, ships (and submarines) remain the quintessential element of maritime presence and power projection. There is no metric for naval strength quite as easily understandable as the number of ships a navy operates and maintains. Much naval strategic planning happening right now in the Pentagon and D.C. think tanks revolves around President Trump’s stated policy of achieving a 355 ship Navy. So, it makes sense that tradition would coalesce around a maxim that prioritizes the ship over all else. After all, sailors literally rely on the ship for their survival, and to return them to their loved ones after deployment.

Yet, for all its traditional primacy in Naval operations, the ship is no more important than the people who operate her. Just as sailors rely on their ship, the ship relies on her crew. It has long been said in naval circles that a new ship is “brought to life” when the commissioning crew runs aboard. What’s needed now is a shift in mindset away from the idea that the ship is something separate that sailors need to prioritize over themselves, toward the idea that sailors and ships are interconnected parts of a larger system that drives toward mission accomplishment, neither being more important than the other. Viewing the ship as a separate and distinct “other” for which one must continually sacrifice their own interests naturally breeds tension and eventually resentment, especially when sailors hear lip service about their wellness being the Navy’s top priority. In truth, the Navy’s top priority is, and always will be, to win our nation’s wars at sea. People, platforms, and payloads are all equally important to that mission. The message to sailors needs to be “take care of the ship, take care of your shipmates, take care of yourself, you are all critical to the mission.” When sailors view themselves as a critical element of a system of mission accomplishment, they begin to find purpose – a reason for the incredible sacrifice all sailors must make. Military leaders have long recognized a sense of purpose as being one of the most powerful motivators for transforming individuals into effective warfighting teams.

The nature of this generation of young sailors is another reason compelling reason to reshape the way the Navy characterizes its priorities. Millennials, as children of the “Peace Dividend” of the 1990s that followed the end of the Cold War, watched their parents pursue individualistic dreams and often expect the opportunity to do the same. Many Millennials were not raised in a time period that was as focused on the same selfless sense of service that some previous generations took for granted. Patriotism just looks different today. However, every American generation has been convinced the following generation was deficient in some way. Even the parents of Tom Brokaw’s “Greatest Generation” probably lamented in 1920 that America’s youth were not ready for the challenges of the “real world.” The prevailing view of Millennials is nothing new, and it’s also not helpful. The fact is, the Navy’s workforce is composed mainly of Millennials, and the challenge of leading them rests with senior leaders, to put it plainly. In this author’s experience, what is often misinterpreted as a “what’s in it for me?” attitude, is in fact a Millennial trying to determine “how do I fit in?” Sailors today seek to thrive personally even as they serve the nation.

Shipmate

In the past, it would have been obvious to say that sailors will put the needs of their shipmates ahead of their own. They are military servicemembers after all, and most of them joined the Navy motivated by some level of selflessness. There are countless times throughout a sailor’s career when they will rightly sacrifice their own interests for the sake of a shipmate, but as a hard and fast rule, it is not necessarily beneficial to the mission for sailors to constantly put themselves last. Sailors sometimes need to prioritize their own health and readiness to ensure they are capable of contributing to the mission. Sleep, for example, is a hot button issue in the Navy right now. Some claim that systemic lack of sleep in the fleet is causing sailors and officers to perform sub-optimally on watch, potentially contributing to two tragic collisions in 2017. To be sure, the Navy needs to examine its own processes to ensure it is affording sailors the requisite time to rest so that they can do their jobs. Still, some responsibility falls on individual sailors to ensure they are getting enough sleep. This is not strictly self-interest. Sailors are one part of a system geared toward mission accomplishment. So, by declining to help out a shipmate on a late night task so they can get enough shut-eye before watch, a sailor is not only taking care of themself, but also supporting their ship’s mission. A four-star admiral once said “Tired staffs are okay, tired commanders are not.” This was not permission for commanders to work their staffs into the ground, rather it was meant to illustrate that staffs have built-in resilience due to depth, whereas commanders represent single points of mission failure. The admiral was directing his commanders to ensure they prioritized their personal health and readiness, because a commander who cannot make sound decisions due to exhaustion could actually endanger the mission, vice support it.

Today, Millennials are often motivated by more individualistic goals. That does not mean, however, that they are not willing to prioritize their shipmates over themselves, and even their ship. Consider a “man overboard” scenario. When a sailor falls into the water, every sailor stops what they are doing and supports the recovery in some way, even if it is just to muster for accountability to help identify the sailor in the water. Prioritizing the sailor above all else is not just contained to a single ship. Every ship and aircraft that can be contacted proceeds to the scene at top speed. Small boats are deployed in questionable sea states. Helicopters might be launched with winds just outside acceptable limits. Short of actual combat or avoiding collision, nothing is more important than recovering an overboard sailor. Every day, sailors put their piled-up workloads aside to give their junior shipmates on- the-job training. Entire career paths, such as Culinary Specialists and Yeomen, are dedicated to the service of other sailors. In fact, every sailor puts in work to serve their shipmates, their ship, and, ultimately, the mission. The key for leaders is to enable sailors to see how they contribute to the mission.

Self

Taking care of yourself is not necessarily selfish. Usually, it is the mindset of “ship, shipmate, self” that leads sailors to perceive those who prioritize their own wellness as “selfish.” On the contrary, when sailors understand how they contribute to the mission, they can maximize mission effectiveness by ensuring they are prepared mentally, physically, and emotionally to give 100 percent focus and effort toward their duties. It is important, of course, for sailors to understand how they fit in to the overall Navy system, and to not take “self-care” too far. Inevitably, there will be times when sailors will only be looking out for themselves, regardless of how their actions affect their shipmates, their ship, or the mission. Clearly, in a “ship, shipmate, self” culture, these sailors are highly frowned upon and quickly corrected. If they cannot be corrected, they are typically shunned.

The problem with this dynamic is the Navy ends up with sailors who are not contributing to the mission. Worse, in almost all cases, selfishness is not an immutable aspect of a sailor’s character, but rather temporary behavior that can be discouraged through sustained command-wide effort. So, the key is understanding one’s role on the ship and in the mission. As one Commanding Officer once put it, “Everyone can contribute. It’s up to the leader to help them figure out how.” Sometimes that might involve creative solutions such as reassigning sailors to other divisions or so-called “Tiger Teams” – small groups dedicated to specific short-term tasks. Sometimes, the answer is as simple as effective command indoctrination, mentorship, and training. Once a sailor truly understands that they are part of a team and how they contribute to the mission, performance will inevitably improve, usually significantly. This growth process requires leaders to exhibit emotional intelligence – the ability to manage emotions in oneself and in others to guide behavior and achieve one’s goals. To help a person who doesn’t want to help themself is often emotionally taxing, and it can be tempting to dismiss that person, but this does nothing to advance the mission.

When the leader views their relationship to an unmotivated sailor not in an adversarial way, but rather in terms of an interconnected system, that leader can begin to see even small ways the sailor might contribute, which is critical because that enables the sailor to then grow their own emotional intelligence. The key insight is that the sailor’s health and readiness are critical elements in an overall readiness system, not afterthoughts to be prioritized behind the ship and shipmates.

Conclusion

Importantly, transitioning from the idea of “ship, shipmate, self” being a set of priorities to a description of an interconnected system not only improves individual sailor wellness, but overall mission effectiveness as well. As much as Navy leadership discusses the importance of sailors and ships, nothing ever comes before the Navy’s mission to “maintain, train and equip combat-ready Naval forces capable of winning wars, deterring aggression and maintaining freedom of the seas.” Fundamentally, accomplishment of the Navy’s mission comes down to individual sailors working as teams to operate the finest ships, submarines, aircraft, and supporting systems in the world. To truly contribute to this mission accomplishment, every level of leadership, from work center supervisors to fleet commanders and beyond, should seek to understand how their organization fits into the overall Navy system. When the Auxiliaries Officer sees how auxiliary services support the ship’s mission, and a Strike Group Commander understands how naval air power supports their fleet, they can empower the most junior sailor with a motivating sense of purpose.

Every sailor should understand more broadly how the Navy contributes to national defense. When a sailor examines how they fits into the overall Navy system, it can be extremely fulfilling to realize that their nation depends on him to keep enemies far from its shores. If Navy leadership wants to move toward a more effective warfighting force, a good first step is the recognition that ship, shipmate, and self are all equally important, interrelated elements dedicated to mission accomplishment.

Jimmy Drennan is the Vice President of CIMSEC. These views are the author’s alone and do not necessarily reflect the position of any government agency.

Featured Image: (June 19, 2018) Hawaii-area Sailors render honors to retired Chief Boatswain’s Mate and Pearl Harbor survivor Ray Emory during a farewell ceremony held before he departs Hawaii to be with family. (U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 2nd Class Justin Pacheco/Released)