If you ask Sailors in the U.S. Navy to list the most important sensors for accomplishing their mission, a likely response is the high-tech name for that fundamental, but decidedly low-tech device – the Mark I Eyeball. In light of recent developments the Mark II may well be only a short way off.

Earlier this year we reported on the conceptual developments coming out of Google’s Project Glass – Augmented Reality (AR) goggles – and began to address their potential applications for the Navy, specifically for damage control teams and bridge and CIC watchstanders. The benefits of such devices are two-fold. First, they are a way to reduce physical requirements, such as carrying or activating a handheld radio with one’s hand, or walking to a console (and perhaps using hands again) to call up information. Second, as the walk to a console highlights AR goggles can facilitate quicker data retrieval when time is of the essence, and deliver it more accurately than when shouted by a shipmate.

Yet there are limitations to AR goggles – both practical and technological.

First, for the time being, AR devices require the same (or more) data exchange capabilities as the handsets they might someday replace. For now this means WiFi, Bluetooth, interior cellular, or radio. Unfortunately, as anyone who has enjoyed communicating during fire-fighting or force protection drills can tell you, large, metal, watertight doors are excellent obstructors of transmissions. While strides have been made over the past decade, range and transmission quality will remain a challenge, especially for roving or expansive interior shipboard watchteams. While it might make sense to install transmitters in areas such as the bridge or CIC for fixed-use watchstanders, setting up transmitters and relays throughout the ship for coverage for larger watchteams is likely to be a more costly endeavor.

Second, voice recognition is integral to much of the system, yet is an imprecise interface for highlighting or selecting physical objects encountered in actual reality (“Siri, what is the distance to that sailboat? No, the other one, with the blue hull. Siri, that’s a buoy”). Some of this can be mitigated by auto-designation systems of the type already in use by most radars (“Siri, kill track 223”). However an auto-designation approach would involve cumbersome doctrine/rule-setting, run the risk of inundating the user with too much data, and still allow a large number of objects to remain outside the system – likely rendering it unmanageable for roving watchstanders.

One solution is letting a Sailors’ eyes do the selecting. This can be achieved by incorporating eye tracking into the AR headsets. Eye tracking is a type of interface that, as the name suggests, allows computers to determine exactly where, and therefore at what, someone’s eyes are looking though the use of miniature cameras and infrared light (for more on the science, read this).

As The Economist reports, the cost of using headset-mounted eye-tracking technology has halved over the past decade, to about $15,000. That’s still a bit pricey. And when the requirements for making headsets ruggedized for military use and integrating them with AR headsets are taken into account the price tag is likely to increase to the point of being unaffordable at present. But the fundamental technology is there and operational.

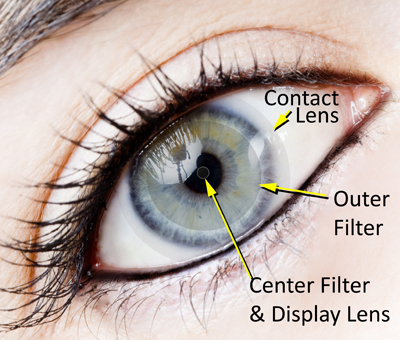

A third AR limitation is that cramming all of the equipment into a headset can make the device pretty unwieldy. Luckily, miniaturization of components is expected to continue apace, and one DARPA project could yield another approach (at the potential loss of an eye-tracking ability). The Soldier Centric Imaging via Computational Cameras (SCENICC) program is funding research to develop contact lenses for both AR and VR displays. As the site describes it, “Instead of oversized virtual reality helmets, digital images are projected onto tiny full-color displays that are very near the eye. These novel contact lenses allow users to focus simultaneously on objects that are close up and far away.” Such contact lenses could be ideal for providing watchstanders a limited heads-up display of the most important data (a ship’s course and speed, for example), but would need an integrated data-receiver.

A third AR limitation is that cramming all of the equipment into a headset can make the device pretty unwieldy. Luckily, miniaturization of components is expected to continue apace, and one DARPA project could yield another approach (at the potential loss of an eye-tracking ability). The Soldier Centric Imaging via Computational Cameras (SCENICC) program is funding research to develop contact lenses for both AR and VR displays. As the site describes it, “Instead of oversized virtual reality helmets, digital images are projected onto tiny full-color displays that are very near the eye. These novel contact lenses allow users to focus simultaneously on objects that are close up and far away.” Such contact lenses could be ideal for providing watchstanders a limited heads-up display of the most important data (a ship’s course and speed, for example), but would need an integrated data-receiver.

Beyond AR

Both eye tracking and the DARPA contact lenses point to other potential naval uses. The Economist describes truckers’ use of eye-tracking to monitor their state of alertness and warn them if they start falling asleep. If the price of integrated headsets drops enough, watchteam leaders may no longer need to flash a light in the eyes of their team to determine who needs a cup of Joe. Already, Eye-Com Corporation has designed an “eye-tracking scuba mask for Navy SEALs that detects fatigue, levels of blood oxygen and nitrogen narcosis, a form of inebriation often experienced on deep dives.”

Naval aviation could also get a boost. A Vermont firm is using eye tracking to help train pilots by monitoring their adherence to checklist procedures. Pilots flying an aircraft from the cockpit or remotely piloting an unmanned system (aerial or otherwise) from the ground could use eye tracking to control movement or weapons targeting.

Likewise the DARPA lenses point to potential drone use. While the lenses are not designed to provide input to a drone – that would have to be done using a different interface such as a traditional joy stick or game controller, until (and if) integrated with eye tracking – VR lenses could provide a more user-friendly, portable way to manually take in the ISR data gathered by the drone (i.e. to see what its camera is seeing). The use for eyeball targeting/selection in naval aviation/naval drones might, however, be surpassed before it is fully developed, by dichotomous forces. One one hand, brain-control interfaces (BCIs) (as demonstrated earlier this year in China) provide more direct control, allowing users essentially to think the aircraft or drone into action. On the other hand, drones will likely become more autonomous, obviating the need for as much direct control (Pete Singer did a good job of breaking down the different drone interface options and levels of autonomy a few years ago in Wired for War).

Yet not everyone is likely to be comfortable plugging equipment into their body. So while BCI technology could similarly work for AR goggles, unless BCI use becomes a military mandate, AR headsets with integrated voice recognition/communication and eye-tracking are likely to be the pinnacle goal for shipboard use. There will undoubtedly be delays. For example, widespread adoption of near-term improvements such as voice-activated radios (or other inputs that don’t require hand-use) would temporarily upset the cost-benefit calculation of continued AR headset development. However, if industry can bring down the cost enough (and the initial reception to Project Glass indicates there could by widespread consumer demand for the technology), the future will contain integrated headsets of some sort, making the good ‘ol eyeball all the more important.

2 thoughts on “The Mark II Eyeball”