The following article is special to our International Maritime Shipping Week. While we often discuss the threats to maritime shipping, this week looks at dangers arising from such global trade, and possible mitigations.

International Maritime Shipping Week requires us to invert our usual thinking – instead of considering threats to merchant shipping, we look at how supposedly innocuous ships threaten the broader world.

What could be more innocuous than cruise ships?

Hundreds of sun-chasing, fun-seeking tourists accompanied by a staff of well-dressed entertainers, professional food service staff and smiling sailors. Nothing could possibly go wrong…

Before I continue, I should note (in what I’m sure is a standard disclaimer for International Maritime Shipping Week) that cruise ship companies are very professional organizations, and I am in no way impugning their ability to keep passengers and property secure. The scenarios proposed herein are entirely hypothetical.*

Now to business.

Cruise ships are different from all other shipping in one important respect – their passengers. Any plan to use the cruise industry as an avenue of attack should take advantage of this. To ignore the passengers would be to give up a potential asset and also inject too much uncertainty into terrorist planning, since sometimes people stumble onto things unexpectedly(as recent reports suggest may have been the case aboard the Achille Lauro in 1985, when the crew’s inconveniently-timed delivery of complimentary fruit caused the four Palestinian hijackers to improvise actions for which they were ill-prepared, according to The Independent [UK]).

One tactic would be to use passengers passively. Packing hundreds or thousands of individuals aboard a ship provides a terrorist his key asymmetric asset – anonymity among the masses. Additionally, a cruise ship brings together large numbers of people who don’t know one another and would have no idea if a particular individual belonged aboard or not. A terrorist can hide in plain sight aboard the ship during transit in a way that wouldn’t be possible aboard a cargo hauler, where any unfamiliar person is immediately apparent. Then, upon arrival at his target port, he can disembark and simply disappear into the country to make mischief. The crew would surely notice a passenger’s absence, but not until all the tourists had been accounted for, and by then the subject would be long gone.

Imagining a more active scenario, passengers could be used as hostages or human shields as cover for some greater plan. Whatever the terrorists may have in mind, authorities will be reluctant to storm aboard the ship when the threat of civilian casualties is high. This may buy enough time for the hijackers to use the cruise ship itself as a weapons platform or as a diversion to enable some other operation to go forward – such as sending operatives ashore in small craft, as in the 2008 Mumbai attack.

More sophisticated, and potentially far more damaging, would be to use the passengers themselves as threat vectors. A terrorist could infect a cruise ship with a slow-acting pathogen, for example. Passengers would walk off the ship unaware of any symptoms and go to their homes all across the country. Only after their trip would the biological weapon begin to manifest itself – and spread. Conceivably this could be done with computer viruses, as well, though it’s not immediately clear why attacking cruise ship passengers as opposed to some other group would be worth the trouble. But where there’s a weakness, someone will exploit it, and the concentrations of people on cruise ships present a juicy target for the initial phase of a “viral” attack.

That said, the most likely malevolent use of a cruise ship is a good, old-fashioned hijacking in the name of propaganda. Cruise ships offer an enormous number of hostages and are media magnets when trouble hits – review the coverage of the Costa Concordia or the Carnival Triumph, turn it up to eleven, and then add the political and diplomatic ramifications that would result. Hijacking a cruise ship may not be innately useful (possible grounds for a later post), but in skilled hands it can cause many global second-order effects far bigger than the fate of one little ship.

You’ll never see “The Love Boat” the same way again.

*According to CIMSEC’s crack team of attorneys, by using the word “herein,” I’ve given this disclaimer legal weight.

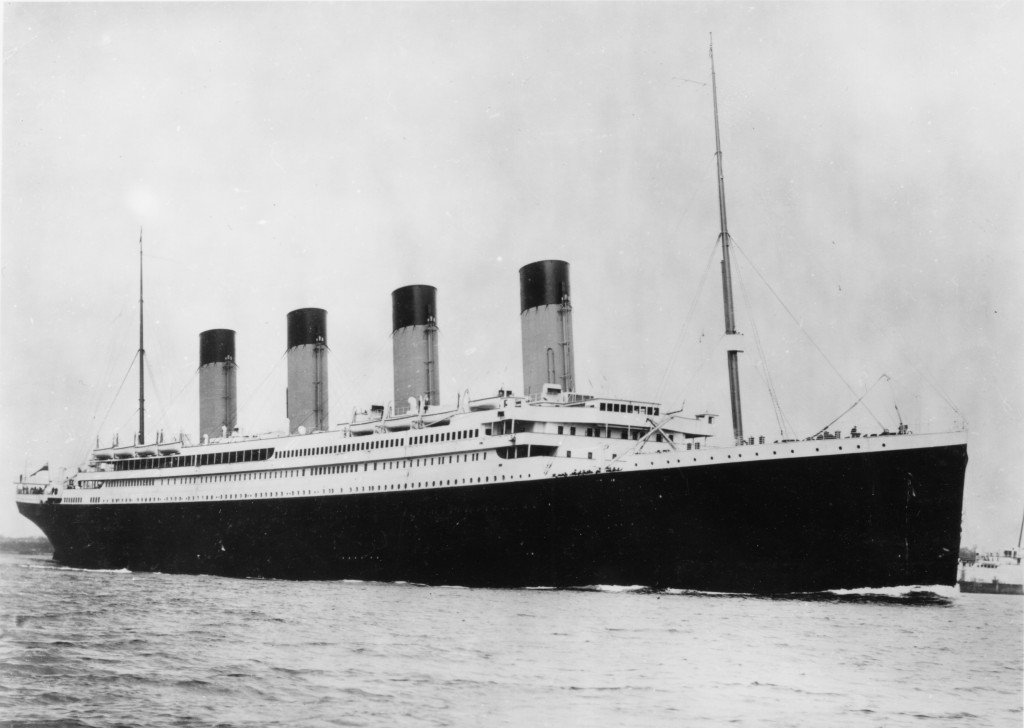

LT Matt McLaughlin is a strategic communications consultant and Navy Reservist whose only cruise ship experience is touring Titanic: The Exhibition. The opinions expressed herein do not represent those of the Department of Defense, Department of the Navy or his employer.