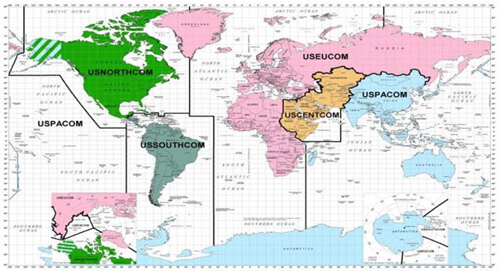

Welcome to the July 2015 Member Round-Up. Our members have had a very productive month discussing three major security topics; the rise of China, the Iranian Nuclear Deal, and the fight against ISIS. A few of the articles are shared here for some light reading over your Labor Day Weekend. If you are a CIMSEC Member and want your own maritime security-related work included in this or upcoming round-ups be sure to contact our Director of Member Publicity at dmp@cimsec.org.

Henry Holst begins our round up discussing the PLA/N’s options for submarine activity in the Taiwan Strait. His article in USNI News states that the Taiwan situation remains the driving force behind the Chinese military buildup. Holst goes into depth discussing the capabilities of the Yuan Type-39A class SSK in a standoff between China and Taiwan/US forces. This article is a must read for all who are interested in the recent developments of the Chinese submarine service.

CIMSEC’s founder, Scott Cheney-Peters, meanwhile discussed the nuances of potential joint aerial patrols in the South China Sea with CSIS’ Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative (AMTI) and joined fellow CIMSECian Ankit Panda from The Diplomat for a podcast discussion of India’s evolving approach to maritime security in East Asia. Also at AMTI, Ben Purser co-authored a piece on China’s airfield construction of Fiery Cross Reef. AMTI’s director, Dr. Mira Rapp-Hooper joined others testifying before a Congressional committee on America’s security role in the South China Sea.

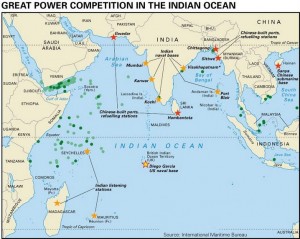

Zachary Keck, of The National Interest, provides the next piece. July was an especially intense month for Mr. Keck, as he wrote 25 articles in July alone. Staying in East and Southeast Asia, Mr. Keck writes that just as China has done in the South China Sea, the PRC could build artificial islands nearer to India as well.  His concern is due to a constitutional amendment in Maldives that was passed in late July. This amendment allows for foreign ownership of Maldives territory. China has rebuffed these concerns and says that they are committed to supporting “the Maldives’ efforts to maintain its sovereignty, independence and territorial integrity.” This piece will be of interest for those that are keeping tabs on Chinese expansionist tendencies.

His concern is due to a constitutional amendment in Maldives that was passed in late July. This amendment allows for foreign ownership of Maldives territory. China has rebuffed these concerns and says that they are committed to supporting “the Maldives’ efforts to maintain its sovereignty, independence and territorial integrity.” This piece will be of interest for those that are keeping tabs on Chinese expansionist tendencies.

Moving on from the Chinese situation and the South China Sea, Shawn VanDiver takes us to the Iranian Plateau and the Persian Gulf to discuss the Iranian nuclear deal now before Congress. He penned two articles last month describing the advantages of the deal. His first article, in Task & Purpose, describes his support for the  deal as a 12 year veteran of the United States Navy. He describes his apprehension and the sense of foreboding transiting the Strait of Hormuz at the sights of a .50 caliber machine gun. The next day his second article on the Iran deal came out in the Huffington Post. This article was slightly different as he focuses more on the stated positions of the then current crop of GOP presidential contenders and Senators. He states that the deal is a new beginning. Well worth the read if you are at all hesitating on the importance of this crucial deal.

deal as a 12 year veteran of the United States Navy. He describes his apprehension and the sense of foreboding transiting the Strait of Hormuz at the sights of a .50 caliber machine gun. The next day his second article on the Iran deal came out in the Huffington Post. This article was slightly different as he focuses more on the stated positions of the then current crop of GOP presidential contenders and Senators. He states that the deal is a new beginning. Well worth the read if you are at all hesitating on the importance of this crucial deal.

For the last mention in our member round up, Admiral James Stavridis spent time last month discussing the role of Turkey in the current fight against ISIS. As former Supreme Commander of NATO forces, Admiral Stavridis is uniquely qualified to render judgement on the role of a critical NATO member in the region, the only one directly affected by ISIS fighters. He was interviewed on ABC’s This Week with George Stephanopoulos. In the same vein, he penned an article in Foreign Policy discussing the importance of NATO use of Incirlik Air Base in Turkey on the Mediterranean Coast. This base is seen as critical to the effort against ISIS in Syria and Iraq.

CIMSECians were busy elsewhere too:

- BJ Armstrong penned “The Brutal Realities of Naval Strategies” and “Guns off Algiers,” and recorded a podcast,”A Novelist and a Historian Walk into a Bar,” all at War on the Rocks. His piece “D – All of The Above: Connecting 21st Century Naval Doctrine to Strategy” appeared at Infinity Journal.

- Darshana Baruah looked into the evolving U.S.-Vietnamese relations.

- Claude Berube reviewed the new novel Ghost Fleet at War on the Rocks.

- Bryan Clark explored how to succeed in “21st-Century Battle Network Competitions” at The National Interest and “America’s Precision Strike Advantage” with Defense News.

- Lauren Dickey asked “After Iran, North Korea Next?” and noted “The Stock Market a Test for China’s Government” at The Diplomat.

- Brett Friedman published “Mass Effect: Information, Communication, and Rhetoric in Warfare” at Infinity Journal. Brett’s new book, 21st Century Ellis, was reviewed over at our partner blog hosted by the Australian Naval Institute.

- Robert Hein wrote “Maintenance, Modernization, and Modules” in Proceedings.

- Armando Heredia analyzed the Philippines’ efforts to reinforce its South China Sea outpost at Second Thomas Shoal with U.S. Naval Institute News.

- Chuck Hill discussed the new U.S. National Military Strategy from a Coast Guard perspective and explored potential upgrades to Bangladesh’s coast guard, among other topics, at Chuck Hill’s CG Blog.

- Nicholas Myhre talked Vertical Launch System (VLS) reloading at sea at the US Naval Institute (USNI) Blog.

- Ankit Panda wrote many pieces at The Diplomat, including dives into China’s persistent Sri Lankan port ambitions, China’s confirmed participation at India’s International Fleet Review next year, and an increase in China’s harassment of Vietnamese fishermen.

- Paul Pryce looked at China’s strategic bomber.

- Dr. Vijay Sakhuja explored the realities of maritime cyber attacks at India’s National Maritime Foundation (NMF).

- Natalie Sambhi was quoted in an article at The Straits Times Indonesian military transparency.

- Erik Sand provided an “Exit Interview” on leaving the Navy at USNI Blog.

- Jacob Stokes co-authored a piece on what the next president needs to know about reforming the national security council at War on the Rocks.

- Chris Rawley delved into “The Islamic State at Sea” at Information Dissemination.

- Michal Thim explained at The Diplomat why “Defending Taiwan is NOT Illegal.”

- Steven Wills jumped into “Post-2015 LCS/Frigate Concepts of Operation” at Information Dissemination.

That is all for July. Stay tuned to CIMSEC for all your maritime security needs.

“A good Navy is not a provocation to war. It is the surest guaranty of peace.”

President Theodore Roosevelt, 2 December 1902

The views expressed above are those of the author’s.