What advice would you give to a smaller nation on the maritime investments it should pursue, and why?

This is the eighth in our series of posts from our Maritime Futures Project. For more information on the contributors, click here. Note: The opinions and views expressed in these posts are those of the authors alone and are presented in their personal capacity. They do not necessarily represent the views of their parent institution U.S. Department of Defense, the U.S. Navy, any other agency, or any other foreign government.

Simon Williams, U.K.

The nation in question must clearly enunciate what it seeks to gain from the maritime realm. Only in doing this will it construct an appropriate approach to its engagement with the sea.

Prof. James Holmes, U.S. Naval War College:

Lesser maritime nations often seem to assume they have to compete symmetrically with the strong in order to accomplish their goals. That would mean that, say, a Vietnam would have to build a navy capable of contending on equal terms with China’s South Sea Fleet in order to fulfill its strategic aims. That need not be true. Here at the College we sometimes debate whether small states have grand strategies, or whether grand strategy is a preserve of the strong. Small coastal states do have grand strategies. In fact, there’s a premium on thinking and acting strategically when you have only meager resources to tap. Our Canadian friends, for instance, take pride in operating across inter-agency boundaries. Small states can’t simply throw resources at problems and expect to solve them. They have to think and invest smart. That’s my first bit of advice.

What kinds of strategies and forces should the weak pursue? Here’s the second bit of advice: they should consult great thinkers of the past. The French Jeune École of the 19th century formulated some fascinating ideas about how to compete with a Royal Navy that ruled the waves. Sir Julian Corbett fashioned a notion of active defense by which an inferior fleet could prevent a greater one from accomplishing its goals. In effect it could hug the stronger fleet, remaining nearby to keep the enemy from exercising command of the sea. Mao Zedong’s writings about active defense also apply in large part to the nautical domain. The notions of sea denial and maritime guerrilla warfare should resonate with smaller powers today. Clinging to an adversary while imposing high costs on him is central to maritime strategies of the weak.

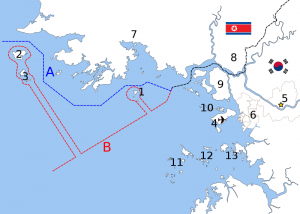

And third, what does that mean in force-structure terms? It means smaller maritime powers should look for inexpensive hardware and tactics that make life tough and expensive for bigger powers. I have urged the Taiwan Navy to downplay its sea-control fleet in favor of platforms like missile-armed fast patrol boats that could give a superior Chinese navy fits. Such acquisitions are worth studying even for a great naval power like Japan. So long as Tokyo caps defense spending at 1 percent of GDP, it has to look to get the most bang it can for the buck. Sea denial should be in its portfolio. Bottom line, lesser powers should refuse to despair about their maritime prospects. They should design their fleets as creatively as possible, taking advantage of the home-field advantage all nations enjoy in their immediate environs. That may mean a navy founded on small craft.

Anonymous, USN:

Protect your resources and people. Make friends with powerful nations that can help guard you.

LT Drew Hamblen, USN:

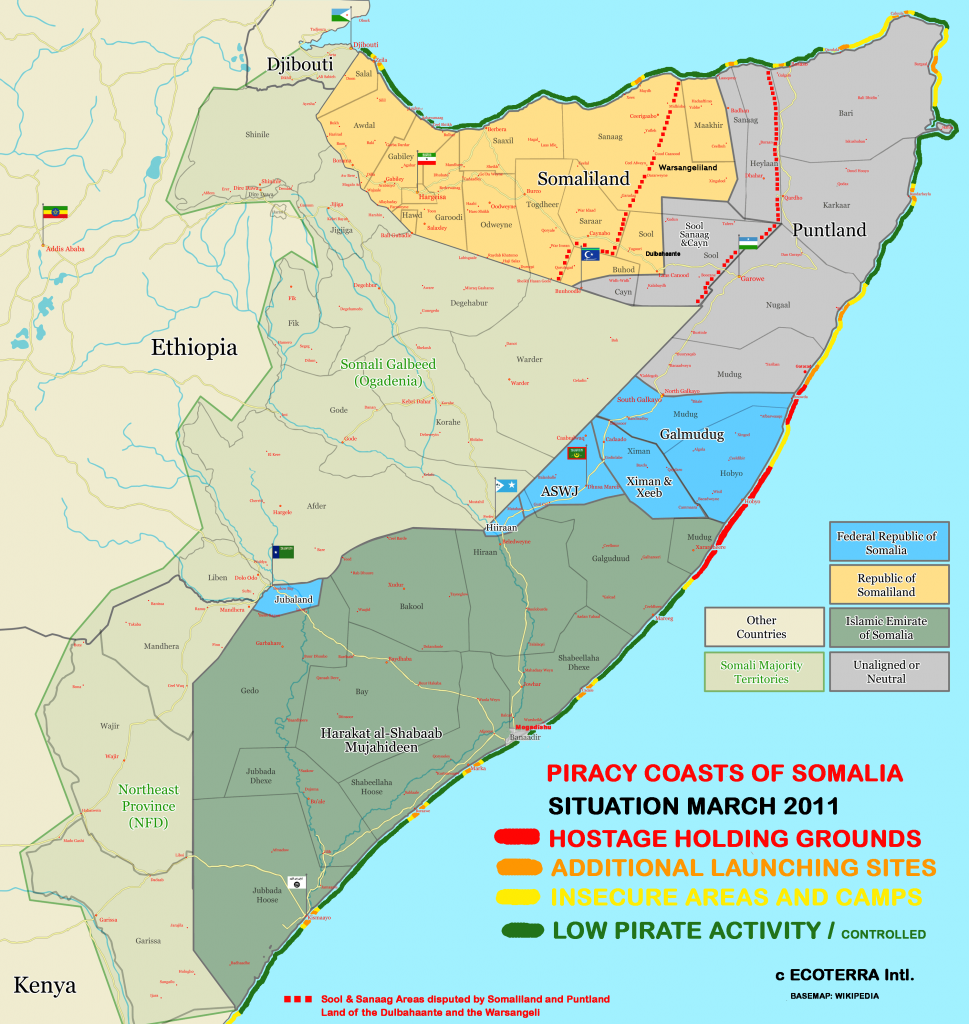

Design high-speed, helicopter- and small boat-capable ships that can combat piracy and enforce maritime law. A few guided-missile cruisers may be needed to augment coastal defenses. Expeditionary navies will increasingly become obsolete in favor of submarine patrols and small surface surveillance units.

Felix Seidler, seidlers-sicherheitspolitik.net, Germany:

My advice would depend on the region. Latin American nations surely do not need blue-water capabilities, and instead should focus on small, mobile units to fight drug trafficking, etc. In conflict zones, my advice would be to build up sophisticated cyber-forces soon. From a cost-benefit perspective, the easiest way for a small nation to target a large one is cyber-warfare. With regard to naval vessels, I would definitely recommend submarines. It does not make any sense for smaller nations to try and get the upper hand on the surface. Instead I would advise using cyber and submarine forces for asymmetric tactics.

Matt Cosner, U.S.:

I believe that smaller maritime nations – particularly those concerned with controlling significant maritime frontiers and resources vice projecting power – would be better served acquiring land-based maritime patrol and reconnaissance aircraft (MPRA) rather than buying additional warships. One needs look only at Japan as an example. Japan has a much smaller ship count (70 vs. 280 ships) than the U.S. Navy, yet fields only slightly fewer MPRA (80 vs. 120 aircraft).

For a smaller maritime nation, say Indonesia or the Philippines, an MPRA doesn’t necessarily have to be something as capable (and expensive!) as the P-3C Orion or P-8A Poseidon. These aircraft are optimized for long-ranged anti-submarine warfare, yet many countries have little need for this specialized capability.

In my opinion the better solution for most smaller maritime nations is something like a marinized Reaper UAS. Persistent maritime ISR is an enormous force multiplier that the U.S. Navy is only beginning to understand with its MQ-4 BAMS. In the context of a smaller nation – a squadron of 5 Reapers could provide persistent (24/7) surveillance over a very wide expanse of water, as well as a kinetic response if/when required.

LT Alan Tweedie, USNR:

Invest in modular small combatants. I can’t stress the modular concept enough, many industries, including civilian shipping companies have been doing it for years. Modularity brings flexibility with lower cost, two must-haves for a small nation.

CDR Chris Rawley, USNR:

Buy small patrol vessels (or even converted commercial/fishing vessels) your country can sustain without external support, be that maintenance contracts or fuel. There is no need to purchase expensive, complicated, technologically intensive “maritime domain awareness” (MDA) solutions. Rather, acquire as many intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) aircraft – whether manned or unmanned – and the infrastructure to support them, as you can afford. Most importantly, invest in a competent and professional boarding team capability. These teams are the main battery of a nascent navy or coast guard with the primary missions of policing coastal waters and controlling maritime borders against smugglers, pirates, and the like.

LTJG Matt Hipple, USN:

Don’t expand beyond your interests. For example, Pakistan has a “navy” with FFGs, but their interests don’t lie beyond their shores and serves little more than targets for India at sea. Maintain a bubble of security and legitimacy within your “realm” using corvettes and a corps of professional highly paid sailors and law-enforcement officers. Find maritime partnerships within which you can grow organically.

Dr. Robert Farley, Professor, University of Kentucky:

The core role of a navy is to secure a state’s maritime interests. For a small, poor nation this will most often involve protection of fisheries, local anti-piracy measures, anti-smuggling, and other missions that run along the divide between military and law enforcement. Small, poor countries should concentrate on developing manageable, reliable, easy-to-maintain flotillas that can conduct these kinds of operations, and on developing a corps of sailors capable of doing their jobs well.

Small rich nations have different problems; many of them (in Europe, for example) already have relatively secure littorals. These states can focus on developing capabilities that will allow them to participate in and contribute to multilateral operations.

CDR Chuck Hill, USCG (Ret.):

Not every coastal nation needs a navy, but they all need a coast guard – see Costa Rica for example. It is their only armed force.

Bryan McGrath, Director, Delex Consulting, Studies and Analysis:

It depends on where that nation is. If it is in the South China Sea, I would recommend that their maritime investments be targeted on understanding the battlespace around their territory. Maritime Domain Awareness (MDA)—from the land, on the sea and in the air.

Sebastian Bruns, Fellow, Institute for Security, University of Kiel, Germany:

Be flexible. Find a niche. Work to provide the right framework and circumstances. Be reliable and somewhat predictable: politically, operationally, and strategically.

Bret Perry, Student, Georgetown University:

Smaller nations should focus on procuring sustainable, simple systems. The following example illustrates my advice: a second- or third-world nation would be better off with a fleet of armed RHIBs (rigid-hull inflatable boats) than one or two larger patrol boats to protect their waters. Many second- or third-world navies lack the capability or willingness to maintain these “larger” ships; as a result, they sit in port and fall out of service. The same sometimes happens to the smaller RHIBs, but since they might have dozens of these, damaged ones can cannibalized for spare parts. These simple systems, combined with investments in training, will allow smaller nations to effectively conduct basic maritime security operations.

YN2(SW) Michael George, USN:

Rather simply, keeping the “quality over quantity” perspective when training, building, and forming their forces will go further than hustling as many ships and troops/sailors out there as possible.

LT Jake Bebber, USN:

Missiles are cheaper than surface or subsurface platforms, and a small nation can probably raise the “entry fee” into their littorals enough to discourage a maritime power like the U.S. (or China for that matter) from operating near their coast with land-based missile systems. If the small nation can afford a few diesel submarines and maritime patrol aircraft, it can significantly increase the cost of power projection over their shores from a larger maritime power. As Lord Nelson said, “A fool’s a man who fights a fort.” Today’s anti-ship cruise missile (ASCM) systems – both land-based and platform based – are the modern equivalent of the 18th century coastal fort. They alone cannot win a war for a smaller nation against a maritime power, but they can certainly discourage one.